Recitative Musick”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

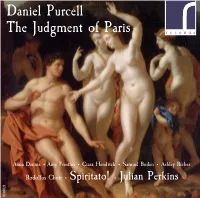

Daniel Purcell the Judgment of Paris

Daniel Purcell The Judgment of Paris Anna Dennis • Amy Freston • Ciara Hendrick • Samuel Boden • Ashley Riches Rodolfus Choir • Spiritato! • Julian Perkins RES10128 Daniel Purcell (c.1664-1717) 1. Symphony [5:40] The Judgment of Paris 2. Mercury: From High Olympus and the Realms Above [4:26] 3. Paris: Symphony for Hoboys to Paris [2:31] 4. Paris: Wherefore dost thou seek [1:26] Venus – Goddess of Love Anna Dennis 5. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (This Radiant fruit behold) [2:12] Amy Freston Pallas – Goddess of War 6. Symphony for Paris [1:46] Ciara Hendricks Juno – Goddess of Marriage Samuel Boden Paris – a shepherd 7. Paris: O Ravishing Delight – Help me Hermes [5:33] Ashley Riches Mercury – Messenger of the Gods 8. Mercury: Symphony for Violins (Fear not Mortal) [2:39] Rodolfus Choir 9. Mercury, Paris & Chorus: Happy thou of Human Race [1:36] Spiritato! 10. Symphony for Juno – Saturnia, Wife of Thundering Jove [2:14] Julian Perkins director 11. Trumpet Sonata for Pallas [2:45] 12. Pallas: This way Mortal, bend thy Eyes [1:49] 13. Venus: Symphony of Fluts for Venus [4:12] 14. Venus, Pallas & Juno: Hither turn thee gentle Swain [1:09] 15. Symphony of all [1:38] 16. Paris: Distracted I turn [1:51] 17. Juno: Symphony for Violins for Juno [1:40] (Let Ambition fire thy Mind) 18. Juno: Let not Toyls of Empire fright [2:17] 19. Chorus: Let Ambition fire thy Mind [0:49] 20. Pallas: Awake, awake! [1:51] 21. Trumpet Flourish – Hark! Hark! The Glorious Voice of War [2:32] 22. -

The Bach Experience

MUSIC AT MARSH CHAPEL 10|11 Scott Allen Jarrett Music Director Sunday, December 12, 2010 – 9:45A.M. The Bach Experience BWV 62: ‘Nunn komm, der Heiden Heiland’ Marsh Chapel Choir and Collegium Scott Allen Jarrett, DMA, presenting General Information - Composed in Leipzig in 1724 for the first Sunday in Advent - Scored for two oboes, horn, continuo and strings; solos for soprano, alto, tenor and bass - Though celebratory as the musical start of the church year, the cantata balances the joyful anticipation of Christ’s coming with reflective gravity as depicted in Luther’s chorale - The text is based wholly on Luther’s 1524 chorale, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.’ While the outer movements are taken directly from Luther, movements 2-5 are adaptations of the verses two through seven by an unknown librettist. - Duration: about 22 minutes Some helpful German words to know . Heiden heathen (nations) Heiland savior bewundert marvel höchste highest Beherrscher ruler Keuschheit purity nicht beflekket unblemished laufen to run streite struggle Schwachen the weak See the morning’s bulletin for a complete translation of Cantata 62. Some helpful music terms to know . Continuo – generally used in Baroque music to indicate the group of instruments who play the bass line, and thereby, establish harmony; usually includes the keyboard instrument (organ or harpsichord), and a combination of cello and bass, and sometimes bassoon. Da capo – literally means ‘from the head’ in Italian; in musical application this means to return to the beginning of the music. As a form (i.e. ‘da capo’ aria), it refers to a style in which a middle section, usually in a different tonal area or key, is followed by an restatement of the opening section: ABA. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

LIBRETTO LOOP” (Created by Todd Woodard)

OPERA WARM UP ACTIVITY: “LIBRETTO LOOP” (created by Todd Woodard) • OBJECTIVE: To build a foundational knowledge of some basic Opera terms through physical and vocal engagement, while simultaneously building energy and ensemble. • STARTING POSITION: A Standing Circle (or “Loop”) • Sample TA Intro: “What is Libretto? … Yes, Libretto might be the text of an opera, but those words are brought to life through music, movement, emotion and ENERGY. So in this game, we are going to use some Opera terms as our simple libretto, and share them by passing ENERGY through, across and within our LOOP, using music, movement, and emotion.” • TERMS with ACTIONS: o RECITATIVE: • Pass LIBRETTO Energy to the person next to you by singing the word “Recitative” to a TA-set or individualized melody with a directional clap • This continues in same direction until someone changes it with a different term o ARIA: “Hold onto the energy before you pass it by taking a solo moment in the spotlight” • Person sings “Aria! Aria! Aria!”, perhaps bending on a knee with arm outstretched, or striking another strong emotional pose • Then pass the energy with “Recitative” or with one of the terms below o VIBRATO • Person with energy shakes hands out in the direction of previous person to induce a vibrato in the voice while singing an extended “Vi- brAAAAA-TOOOOOO”) • This bounces the energy back to the previous person and they continue with energy pass in the opposite direction o MELODY • First person sings “Melody” to a melody of their choice as they pass it to another person -

Iolanta Bluebeard's Castle

iolantaPETER TCHAIKOVSKY AND bluebeard’sBÉLA BARTÓK castle conductor Iolanta Valery Gergiev Lyric opera in one act production Libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky, Mariusz Treliński based on the play King René’s Daughter set designer by Henrik Hertz Boris Kudlička costume designer Bluebeard’s Castle Marek Adamski Opera in one act lighting designer Marc Heinz Libretto by Béla Balázs, after a fairy tale by Charles Perrault choreographer Tomasz Wygoda Saturday, February 14, 2015 video projection designer 12:30–3:45 PM Bartek Macias sound designer New Production Mark Grey dramaturg The productions of Iolanta and Bluebeard’s Castle Piotr Gruszczyński were made possible by a generous gift from Ambassador and Mrs. Nicholas F. Taubman general manager Peter Gelb Additional funding was received from Mrs. Veronica Atkins; Dr. Magdalena Berenyi, in memory of Dr. Kalman Berenyi; music director and the National Endowment for the Arts James Levine principal conductor Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and Fabio Luisi Teatr Wielki–Polish National Opera The 5th Metropolitan Opera performance of PETER TCHAIKOVSKY’S This performance iolanta is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored conductor by Toll Brothers, Valery Gergiev America’s luxury in order of vocal appearance homebuilder®, with generous long-term marta duke robert support from Mzia Nioradze Aleksei Markov The Annenberg iol anta vaudémont Foundation, The Anna Netrebko Piotr Beczala Neubauer Family Foundation, the brigit te Vincent A. Stabile Katherine Whyte Endowment for Broadcast Media, l aur a and contributions Cassandra Zoé Velasco from listeners bertr and worldwide. Matt Boehler There is no alméric Toll Brothers– Keith Jameson Metropolitan Opera Quiz in List Hall today. -

Theatre of Magic Programme Notes

Theatre of Magic PROGRAMME NOTES The English flocked to the theatres when they were reopened after the Restoration. Old plays by Shakespeare, Beaumont, and Fletcher were reworked and eventually supplemented by works by new playwrights. Music, dance, and spectacle were gradually added to complement the drama. The English had not yet embraced opera as it was understood on the Continent, but the amount of music added to the plays became too significant to ignore, and the English writer Roger North invented the term “semi-opera” to describe these entertainments of “half Musick and half Drama.” The leading parts continued to be spoken by actors, while vocal music was allotted to minor characters, whose contributions were essentially diversions, rarely essential to the action. To this was added instrumental music to accompany dance, set the mood, or accompany scene changes. Our concerts this week open with excerpts from two of these semi-operas, both adaptations of Shakespeare’s magical plays, The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Matthew Locke was arguably England’s leading composer at the time of the Restoration in 1660. He became very active in London’s commercial theatres, contributing music for countless plays. He is best known today for the instrumental music he wrote for The Tempest, produced by Thomas Shadwell in 1674. The text of the semi-opera was adapted by Shadwell from an earlier adaptation (1667) of Shakespeare’s original by John Dryden and William Davenant. Shadwell’s version of the play remained popular for some 75 years. Locke’s opening Curtain Tune is particularly striking: it is a musical depiction of the storm that precedes the play, complete with detailed instructions to the performers (including the instruction to play “Violently” at the height of the storm). -

The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years Of

Press release | 30/3/2017 | acr | Updated: July 2017 The 2017/18 Season: 70 Years of the Komische Oper Berlin – 70 Years of the Future of Opera 10 premieres for this major birthday, two of which are reencounters with titles of legendary Felsenstein productions, two are world premieres and four are operatic milestones of the 20 th century. 70 years ago, Walter Felsenstein founded the Komische Oper as a place where musical theatre makers were not content to rest on the laurels of opera’s rich traditions, but continually questioned it in terms of its relevance and sustainability. In our 2017/18 anniversary season, together with their team, our Intendant and Chefregisseur Barrie Kosky and the Managing Director Susanne Moser are putting this aim into practice once again by way of a diverse program – with special highlights to celebrate our 70 th birthday. From Baroque opera to operettas and musicals, the musical milestones of 20 th century operatic works, right through to new premieres of operas for children, with works by Georg Friedrich Handel through to Philip Glass, from Jacques Offenbach to Jerry Bock, from Claude Debussy to Dmitri Shostakovich, staged both by some of the most distinguished directors of our time as well as directorial newcomers. New Productions Our 70 th birthday will be celebrated not just with a huge birthday cake on 3 December, but also with two anniversary productions. Two works which enjoyed great success as legendary Felsenstein productions are returning in new productions. Barrie Kosky is staging Jerry Brock’s musical Fiddler on the Roof , with Max Hopp/Markus John and Dagmar Manzel in the lead roles, and the magician of the theatre, Stefan Herheim, will present Jacques Offenbach’s operetta Barbe- bleue in a new, German and French version. -

A European Singspiel

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2012 Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel Zachary Bryant Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bryant, Zachary, "Die Zauberflöte: A urE opean Singspiel" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 116. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. r DIE ZAUBEFL5TE: A EUROPEAN SINGSPIEL Zachary Bryant Die Zauberflote: A European Singspiel by Zachary Bryant A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the Bachelor of Arts in Music College of the Arts Columbus State University Thesis Advisor JfAAlj LtKMrkZny Date TttZfQjQ/Aj Committee Member /1^^^^^^^C^ZL^>>^AUJJ^AJ (?YUI£^"QdJu**)^-) Date ^- /-/<£ Director, Honors Program^fSs^^/O ^J- 7^—^ Date W3//±- Through modern-day globalization, the cultures of the world are shared on a daily basis and are integrated into the lives of nearly every person. This reality seems to go unnoticed by most, but the fact remains that many individuals and their societies have formed a cultural identity from the combination of many foreign influences. Such a multicultural identity can be seen particularly in music. Composers, artists, and performers alike frequently seek to incorporate separate elements of style in their own identity. One of the earliest examples of this tradition is the German Singspiel. -

122 a Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. Music Is As Old As The

122 A Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. A CENTURY OF GRAND OPERA IN PHILADELPHIA. A Historical Summary read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Monday Evening, January 12, 1920. BY JOHN CURTIS. Music is as old as the world itself; the Drama dates from before the Christian era. Combined in the form of Grand Opera as we know it today they delighted the Florentines in the sixteenth century, when Peri gave "Dafne" to the world, although the ancient Greeks listened to great choruses as incidents of their comedies and tragedies. Started by Peri, opera gradually found its way to France, Germany, and through Europe. It was the last form of entertainment to cross the At- lantic to the new world, and while some works of the great old-time composers were heard in New York, Charleston and New Orleans in the eighteenth century, Philadelphia did not experience the pleasure until 1818 was drawing to a close, and so this city rounded out its first century of Grand Opera a little more than a year ago. But it was a century full of interest and incident. In those hundred years Philadelphia heard 276 different Grand Operas. Thirty of these were first heard in America on a Philadelphia stage, and fourteen had their first presentation on any stage in this city. There were times when half a dozen travelling companies bid for our patronage each season; now we have one. One year Mr. Hinrichs gave us seven solid months of opera, with seven performances weekly; now we are permitted to attend sixteen performances a year, unless some wandering organization cares to take a chance with us. -

Lully's Psyche (1671) and Locke's Psyche (1675)

LULLY'S PSYCHE (1671) AND LOCKE'S PSYCHE (1675) CONTRASTING NATIONAL APPROACHES TO MUSICAL TRAGEDY IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY ' •• by HELEN LLOY WIESE B.A. (Special) The University of Alberta, 1980 B. Mus., The University of Calgary, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS • in.. • THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF MUSIC We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1991 © Helen Hoy Wiese, 1991 In presenting this hesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of Kos'iC The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date ~7 Ocf I DE-6 (2/68) ABSTRACT The English semi-opera, Psyche (1675), written by Thomas Shadwell, with music by Matthew Locke, was thought at the time of its performance to be a mere copy of Psyche (1671), a French tragedie-ballet by Moli&re, Pierre Corneille, and Philippe Quinault, with music by Jean- Baptiste Lully. This view, accompanied by a certain attitude that the French version was far superior to the English, continued well into the twentieth century.