Central Opera Service Bulletin • Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium Programme

Singing a Song in a Foreign Land a celebration of music by émigré composers Symposium 21-23 February 2014 and The Eranda Foundation Supported by the Culture Programme of the European Union Royal College of Music, London | www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Follow the project on the RCM website: www.rcm.ac.uk/singingasong Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: Symposium Schedule FRIDAY 21 FEBRUARY 10.00am Welcome by Colin Lawson, RCM Director Introduction by Norbert Meyn, project curator & Volker Ahmels, coordinator of the EU funded ESTHER project 10.30-11.30am Session 1. Chair: Norbert Meyn (RCM) Singing a Song in a Foreign Land: The cultural impact on Britain of the “Hitler Émigrés” Daniel Snowman (Institute of Historical Research, University of London) 11.30am Tea & Coffee 12.00-1.30pm Session 2. Chair: Amanda Glauert (RCM) From somebody to nobody overnight – Berthold Goldschmidt’s battle for recognition Bernard Keeffe The Shock of Exile: Hans Keller – the re-making of a Viennese musician Alison Garnham (King’s College, London) Keeping Memories Alive: The story of Anita Lasker-Wallfisch and Peter Wallfisch Volker Ahmels (Festival Verfemte Musik Schwerin) talks to Anita Lasker-Wallfisch 1.30pm Lunch 2.30-4.00pm Session 3. Chair: Daniel Snowman Xenophobia and protectionism: attitudes to the arrival of Austro-German refugee musicians in the UK during the 1930s Erik Levi (Royal Holloway) Elena Gerhardt (1883-1961) – the extraordinary emigration of the Lieder-singer from Leipzig Jutta Raab Hansen “Productive as I never was before”: Robert Kahn in England Steffen Fahl 4.00pm Tea & Coffee 4.30-5.30pm Session 4. -

OCTOBER 2002 Winner for PARENTS, EDUCATORS & STUDENTS

Award www.EDUCATIONUPDATE.com Volume VIII, No. 2 • New York City • OCTOBER 2002 Winner FOR PARENTS, EDUCATORS & STUDENTS JOSHUA BELL Virtuoso Educator U.S. POSTAGE PAID U.S. POSTAGE VOORHEES, NJ Permit No.500 PRSRT STD. 2 Award EDUCATION UPDATE ■ FOR PARENTS, EDUCATORS & STUDENTS ■ OCTOBER 2002 Winner GUEST EDITORIAL EDUCATION UPDATE Leadership in Our Schools: The Principal Part Mailing Address: 276 5th Avenue, Suite 1005 By CHARLOTTE K. FRANK, Ph.D. dren with their studies; dealing with children place. Principal means, quite literally, taking New York, NY 10001 Over this century, countless “magic bullets” with emotional or behavioral problems; follow- the principal role of leadership on the team that email: [email protected] have been suggested for reforming our schools. ing and implementing federal rules regarding contributes to effective learning. That team www.educationupdate.com In the 1920s, a progressive movement sought to special education; and taking on such other must also include parents and members of the Tel: 212-481-5519 eliminate curricula and external standards. In roles as union negotiator, community and par- community, who, so often, are eager to help if Fax: 212-481-3919 the 1950s, we were advised that the answer was ent public relations liaison; master of play- only they were personally called upon and to create fewer, larger schools out of the many, ground rules, bus schedules and budgets; and, guided in making their specific contributions. smaller ones—yet today, we see many larger in some cases, emergency plumber. But seeing where they can help, and personally PUBLISHER AND EDITOR: schools being divided into smaller learning School leadership today is upside down. -

01-11-2019 Porgy Eve.Indd

THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess By George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin conductor Opera in two acts David Robertson Saturday, January 11, 2020 production 7:30–10:50 PM James Robinson set designer New Production Michael Yeargan costume designer Catherine Zuber lighting designer The production of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Donald Holder Bess was made possible by a generous gift from projection designer Luke Halls The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund and Douglas Dockery Thomas choreographer Camille A. Brown fight director David Leong general manager Peter Gelb Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam; and music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin English National Opera 2019–20 SEASON The 63rd Metropolitan Opera performance of THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess conductor David Robertson in order of vocal appearance cl ar a a detective Janai Brugger Grant Neale mingo lily Errin Duane Brooks Tichina Vaughn* sportin’ life a policeman Frederick Ballentine Bobby Mittelstadt jake an undertaker Donovan Singletary* Damien Geter serena annie Latonia Moore Chanáe Curtis robbins “l aw yer” fr a zier Chauncey Packer Arthur Woodley jim nel son Norman Garrett Jonathan Tuzo peter str awberry woman Jamez McCorkle Aundi Marie Moore maria cr ab man Denyce Graves Chauncey Packer porgy a coroner Kevin Short Michael Lewis crown scipio Alfred Walker* Neo Randall bess Angel Blue Saturday, January 11, 2020, 7:30–10:50PM The worldwide copyrights in the works of George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin for this presentation are licensed by the Gershwin family. GERSHWIN is a registered trademark of Gershwin Enterprises. Porgy and Bess is a registered trademark of Porgy and Bess Enterprises. -

Eberhard Waechter“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Eberhard Waechter“ Verfasserin Mayr Nicoletta angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011 Studienkennzahl: A 317 Studienrichtung: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuerin: Univ.-Prof.Dr. Hilde Haider-Pregler Dank Ich danke vor allem meiner Betreuerin Frau Professor Haider, dass Sie mir mein Thema bewilligt hat und mir mit Rat und Tat zur Seite stand. Ich danke der Familie Waechter und Frau Anneliese Sch. für die Bereitstellung des Materials. Ich danke meiner Schwester Romy und meiner „Seelenverwandten“ Sheila und all meinen Freunden für ihre emotionale Unterstützung und die zahlreichen motivierenden Gespräche. Ich danke meinem Bruder Florian für die Hilfe im Bereich der Computertechnik. Ein großer Dank gilt meiner Tante Edith, einfach dafür, dass es dich gibt. Außerdem danke ich meinen Großeltern, dass sie meine Liebe zur Musik und zur Oper stets enthusiastisch aufgenommen haben und mit mir Jahr für Jahr die Operettenfestspiele in Bad Ischl besucht haben. Ich widme meine Diplomarbeit meinen lieben Eltern. Sie haben mich in den letzten Jahren immer wieder finanziell unterstützt und mir daher eine schöne Studienzeit ermöglicht haben. Außerdem haben sie meine Liebe und Leidenschaft für die Oper stets unterstützt, mich mit Büchern, Videos und CD-Aufnahmen belohnt. Ich danke euch für eure Geduld und euer Verständnis für eure oft komplizierte und theaterbessene Tochter. Ich bin glücklich und froh, so tolle Eltern zu haben. Inhalt 1 Einleitung .......................................................................................... -

COC162145 365 Strategicplan

A VISION FOR THE NEXT FIVE YEARS COC365 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE PLANNING COMMITTEE Alexander Neef General Director Rob Lamb Managing Director In October 2014, a project was initiated by General Director Alfred Caron Alexander Neef to develop a management-driven strategic plan Director, Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts Lindy Cowan, CPA, CA Director of Finance and Administration to guide the Canadian Opera Company for the next five years. Christie Darville Chief Advancement Officer Steve Kelley Chief Communications Officer The COC’s executive leadership team, in governance oversight and input throughout Peter Lamb Director of Production collaboration with a management consultant, the process. Additionally, the process was Roberto Mauro Director of Music and Artistic Administration developed an overarching vision and mission informed by two Board retreats, individual for the company, as well as a basic plan for meetings with all senior managers, a The COC recognizes the invaluable input and contributions to the strategic planning process of implementation and accountability. The management retreat, as well as consultations its Board of Directors under the chairmanship of then-Chair Mr. Tony Arrell, the Canadian Opera 2014/2015 COC Board of Directors provided with a number of external COC stakeholders. Foundation Board of Directors, as well as all members of COC senior management. STAGES OF EXECUTION COC365 ABOUT US • The Canadian Opera Company is the largest • Created the COC Ensemble Studio in 1980, SHARING CONSULTATION REALIZATION producer of opera in Canada, and one of the one of the world’s premier training programs THE PLAN AND INTERNALLY AND INTERNALLY FEEDBACK EXTERNALLY five largest in North America. -

The Egg Center for the Performing Arts Albany, New York Kitty Carlisle Hart Theatre Technical Specifications

The Egg Center for the Performing Arts Albany, New York Kitty Carlisle Hart Theatre Technical Specifications 1 | Hart Theatre Tech Specs - T h e E g g DIRECTIONS DO NOT USE GPS TO GET TO THE EGG. IT WILL SEND YOU TO THE WRONG PLACE. WE DO NOT HAVE A PHYSICAL STREET ADDRESS From the South (New York City): New York State Throughway/I-87 North to exit 23/787 N. Take 787 N to exit 3. Follow signs towards the Empire State Plaza. Loading dock A will be the first turn off on your right as your enter the tunnel. From the North (Montreal): I-87 South to exit 1A/I-90 east. Take exit 6A/787 S towards Albany downtown. Take exit 3A. Follow signs to the Empire State Plaza. Loading dock A will be the first turn off on your right as your enter the tunnel. From the East (Boston): I-90 W. Take exit 6A/787 S towards Albany downtown. Take exit 3A. Follow signs to the Empire State Plaza. Loading dock A will be the first turn off on your right as your enter the tunnel. From the West (Buffalo): I-90 E to exit 24 (exiting the Throughway). Continue on I-90 E to exit 6A/787 S towards Albany downtown. Take exit 3A. Follow signs to the Empire State Plaza. Loading dock A will be the first turn off on your right as your enter the tunnel. o For non-truck vehicle parking follow signs to visitor parking. o Please contact the Production Manager if you need directions from any local hotel to The Egg’s loading dock or visitor parking. -

Luciano Pavarotti Is Dead at 71

September 6, 2007 Luciano Pavarotti Is Dead at 71 By BERNARD HOLLAND Luciano Pavarotti, the Italian singer whose ringing, pristine sound set a standard for operatic tenors of the postwar era, died Thursday at his home near Modena, in northern Italy. He was 71. His death was announced by his manager, Terri Robson. The cause was pancreatic cancer. In July 2006 he underwent surgery for the cancer in New York, and he had made no public appearances since then. He was hospitalized again this summer and released on Aug. 25. Like Enrico Caruso and Jenny Lind before him, Mr. Pavarotti extended his presence far beyond the limits of Italian opera. He became a titan of pop culture. Millions saw him on television and found in his expansive personality, childlike charm and generous figure a link to an art form with which many had only a glancing familiarity. Early in his career and into the 1970s he devoted himself with single- mindedness to his serious opera and recital career, quickly establishing his rich sound as the great male operatic voice of his generation — the “King of the High Cs,” as his popular nickname had it. By the 1980s he expanded his franchise exponentially with the Three Tenors projects, in which he shared the stage with Plácido Domingo and José Carreras, first in concerts associated with the World Cup and later in world tours. Most critics agreed that it was Mr. Pavarotti’s charisma that made the collaboration such a success. The Three Tenors phenomenon only broadened his already huge audience and sold millions of recordings and videos. -

570034Bk Hasse 1/9/09 6:05 PM Page 8

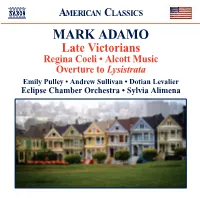

559258bk Adamo:570034bk Hasse 1/9/09 6:05 PM Page 8 Advent as I sat in Most Holy Redeemer SINGER The life we have is very great; Church. The life we are to see AMERICAN CLASSICS Surpasses it because we know SINGER Co-workers. Strangers. Teen-agers. It is infinity. Pensioners. They washed his dishes. But when all space has been beheld VOICE A black man in a checkered sports coat. The And all dominion shown; pink-haired punkess with a jewel in her nose. The smallest human heart’s extent MARK ADAMO The gay couple in middle age. Reduces it to none. SINGER They kissed her on his lips, where once there VOICE These learned to love what is corruptible, Late Victorians were lips. They kissed her on his lips. while I, I, I, I shift my tailbone upon the cold, hard pew. VOICE These know the weight of bodies. Regina Coeli • Alcott Music Finale: Orchestra. Overture to Lysistrata * “Late Victorians” by Richard Rodriguez. Copyright © 1990 by Richard Rodriguez. Originally appeared in Harper’s Magazine (October 1990). By permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc., on behalf of the author. Emily Pulley • Andrew Sullivan • Dotian Levalier Mark Adamo Eclipse Chamber Orchestra • Sylvia Alimena Mark Adamo’s most recent première is Four Angels: Concerto for Harp and Orchestra, introduced by the National Symphony Orchestra in June 2007. His second opera, Lysistrata: or, The Nude Goddess, bowed in March 2006 at New York City Opera, at which Adamo served five years as composer-in-residence. Lysistrata was commissioned and introduced by Houston Grand Opera for its fiftieth season in March 2005. -

Spotlight on Joel Ivany, Assistant Director

Spotlight on Joel Ivany, Assistant Director The Canadian Opera Company has hired a new assistant director to work on La Bohème. This is a prestigious BIOGRAPHY: Stage position for a young Canadian director. Joel Ivany has Director Joel Ivany trained and prepared and is ready for the challenge. He recently apprenticed spoke with us about how his life experiences have shaped under Tim Albery his work today. at the Canadian Opera Company Q: What is something from your early memories that for their acclaimed informs how you work as a director today? production of War and Peace. Directing Joel: There were four of us growing up; an older sister, credits this past summer and a younger sister and brother. I was brought up on included a new work, Sound of Music, Oliver, Mary Poppins and Babes in Knotty Together in Toyland. We’d watch them over and over and over again. Dublin, Ireland, Hänsel I think I get a lot of my ideas and theatricality from those und Gretel in Edmonton, Alberta and Haydn’s La early experiences. Canterina in Sulmona, Italy. His directing credits include such productions as: Copland’s The Tender Q: You have directed operas in Ireland and Italy for Land, Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret, Mozart’s Die different companies. Is the COC any different? More Zauberflöte and associate stage director for the exciting? More nerve wracking? University of Toronto Opera School’s production of Handel’s Ariodante. This past January he Joel: To be an assistant director at the Canadian Opera was involved in collaborating and staging three Company is definitely exciting. -

Philharmonic Au Dito R 1 U M

LUBOSHUTZ and NEMENOFF April 4, 1948 DRAPER and ADLER April 10, 1948 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN April 27, 1948 MENUHIN April 29, 1948 NELSON EDDY May 1, 1948 PHILHARMONIC AU DITO R 1 U M VOL. XLIV TENTH ISSUE Nos. 68 to 72 RUDOLF f No S® Beethoven: S°"^„passionala") Minor, Op. S’ ’e( MM.71l -SSsr0*“” « >"c Beethoven. h6tique") B1DÛ SAYÂO o»a>a°;'h"!™ »no. Celeb'“’ed °P” CoW»b» _ ------------------------- RUOOtf bKch . St«» --------------THE pWUde'Pw»®rc’^®®?ra Iren* W°s’ „„a olh.r,„. sr.oi «■ o'--d s,°3"' RUDOLF SERKIN >. among the scores of great artists who choose to record exclusively for COLUMBIA RECORDS Page One 1948 MEET THE ARTISTS 1949 /leJ'Uj.m&n, DeLuxe Selective Course Your Choice of 12 out of 18 $10 - $17 - $22 - $27 plus Tax (Subject to Change) HOROWITZ DEC. 7 HEIFETZ JAN. 11 SPECIAL EVENT SPECIAL EVENT 1. ORICINAL DON COSSACK CHORUS & DANCERS, Jaroff, Director Tues. Nov. 1 6 2. ICOR CORIN, A Baritone with a thrilling voice and dynamic personality . Tues. Nov. 23 3. To be Announced Later 4. PATRICE MUNSEL......................................................................................................... Tues. Jan. IS Will again enchant us-by her beautiful voice and great personal charm. 5. MIKLOS GAFNI, Sensational Hungarian Tenor...................................................... Tues. Jan. 25 6. To be Announced Later 7. ROBERT CASADESUS, Master Pianist . Always a “Must”...............................Tues. Feb. 8 8. BLANCHE THEBOM, Voice . Beauty . Personality....................................Tues. Feb. 15 9. MARIAN ANDERSON, America’s Greatest Contralto................................. Sun. Mat. Feb. 27 10. RUDOLF FIRKUSNY..................................................................................................Tues. March 1 Whose most sensational success on Feb. 29 last, seated him firmly, according to verdict of audience and critics alike, among the few Master Pianists now living. -

Choral Union Concert Series

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY Charles A. Sink, President Thor Johnson, Guest Conductor Lester McCoy, Associate Conductor Eighth Concert 1950-1951 Complete Series 3050 Seventy-second Annual Choral Union Concert Series CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RAFAEL KUBELIK, Conductor SUNDAY EVENING, MARCH 4, 1951 AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Overture to "The School for Scandal" BARBER Symphony No. 1 in D major, Op. 60 DVORAK Allegro non tanto * Adagio Scherzo (furient) Finale—allegro con spirito INTERMISSION Theme and Four Variations ("The Four Temperaments") for String Orchestra and Piano HINDEMITH Theme Variation No. 1: Melancholic Variation No. 2: Sanguine Variation No. 3: Phlegmatic Variation No. 4: Choleric GEORGE SCHICK at the Piano Prelude to "The Mastersingers of Nuremberg" .... WAGNER The Chicago Symphony Orchestra uses the Baldwin piano, and records exclusively for R.CA. Victor. NOTE.—The University Musical Society has presented the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on pre vious occasions as follows: Choral Union Series, Theodore Thomas, conductor (8); in thirty-one May Festivals (1905-1935 inclusive), and in the Choral Union Series, Nov. 2, 1936 and Nov. 30, 1941, Frederick Stock, conductor; Mar. 19, 1945, Jan. 31, 1946, and Mar. 16, 1947, Desire Defauw, conductor; Oct. 26, 1947, Artur Rodzinski, conductor; Mar. 27, 1949, Fritz Busch, Guest Conductor; and Mar. 12, 1950, Fritz Reiner, Guest Conductor. ARS LONGA VITA BREVIS PROGRAM NOTES By FELIX BOROWSKI (Taken from the Program Book of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra) Overture to "The School for Scandal" .... SAMUEL BARBER The overture to "The School for Scandal" was composed in 1932 and was per formed for the first time at a summer concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra at Robin Hood Dell, Philadelphia, August 30, 1933. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 93, 1973-1974

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THURSDAY A6 FRIDAY-SATURDAY 22 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President PHILIP K. ALLEN SIDNEY STONEMAN JOHN L. THORNDIKE Vice-President Vice-President Treasurer VERNON R. ALDEN MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK JOHN T. NOONAN ALLEN G. BARRY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON MRS JAMES H. PERKINS MRS JOHN M. BRADLEY E. MORTON JENNINGS JR IRVING W. RABB RICHARD P. CHAPMAN EDWARD M. KENNEDY PAUL C. REARDON ABRAM T. COLLIER EDWARD G. MURRAY MRS GEORGE LEE SARGENT ARCHIE C EPPS III JOHN HOYT STOOKEY TRUSTEES EMERITUS HENRY B. CABOT HENRY A. LAUGHLIN PALFREY PERKINS FRANCIS W. HATCH EDWARD A. TAFT ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. PERRY JR THOMAS W. MORRIS Executive Director Manager PAUL BRONSTEIN JOHN H. CURTIS MARY H. SMITH Business Manager Public Relations Director Assistant to the Manager FORRESTER C. SMITH DANIEL R. GUSTIN RICHARD C. WHITE Development Director Administrator of Assistant to Educational Affairs the Manager DONALD W. MACKENZIE JAMES F. KILEY Operations Manager, Operations Manager, Symphony Hall Tanglewood HARRY NEVILLE Program Editor Copyright © 1974 by Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS ^H jgfism SPRING LINES" Outline your approach to spring. In greater detail with our hand- somely tailored, single breasted, navy wool worsted coat. Subtly smart with yoked de- tail at front and back. Elegantly fluid with back panel. A refined spring line worth wearing. $150. Coats. Boston Chestnut Hill Northshore Shopping Center South Shore PlazaBurlington Mall Wellesley BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS & MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS Principal Guest Conductors NINETY-THIRD SEASON 1973-1974 THE BOARD OF OVERSEERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC.