PROSPECTS for CANADA Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

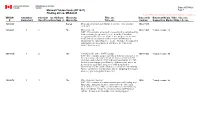

Finding Aid No. MSS2443 Maxwell Yalden Fonds

Date: 2017-03-21 Maxwell Yalden fonds (R11847) Page 1 Finding aid no. MSS2443 Report: Y:\APP\Impromptu75\Mikan\Reports\Description_Reports\finding_aids_&_subcontainers.imr MIKAN Container File/Item Cr. file/item Hierarchy Title, etc Date of/de Extent or Media / Dim. / Access # Contenant Dos./PièceDos./item cr. Hiérarchie Titre, etc création Support ou Média / Dim. / Accès 3684860 Series Department of External Affairs [textual record, graphic 1960-1989 material] 3684863 1 1 File Disarmament 1960-1963 Textual records / 10 S&C : File consists of records created and accumulated by Yalden during the period he served on the Canadian delegation to the Geneva Conference on disarmament in 1960 and the department's Disarmament Division in Ottawa for the following three years. Includes background information on disarmament and notes by Yalden on Soviet disarmament. 3684870 1 2 File Canada and France NATO Europe 1964-1967 Textual records / 90 S&C : File consists of material when Yalden was posted at the Canadian embassy in Paris as 1st secretary in 1963 and then counsellor in 1965 and return to Ottawa in 1967. Includes material prepared for the Ambassador, notes on French Foreign Policy, notes by Yalden and other documents relating to the European economic community. Notes, comments, memoranda, drafts, outgoing messages and excerpts from printed material. 3684874 1 3 File Miscelleneous memos 1968 Textual records / 90 S&C : File consists of administration material relating to a long-range program for travel abroad by the Governor General Jules Léger when Yalden was special advisor to Marcel Cadieux, Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs. Includes memoranda, letter and proposal. -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

The Patriation and Quebec Veto References: the Supreme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution 2011 Canliidocs 443 Peter H

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 54 (2011) Article 3 The aP triation and Quebec Veto References: The Supreme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution 2011 CanLIIDocs 443 Peter H. Russell Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Russell, Peter H.. "The aP triation and Quebec Veto References: The uS preme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 54. (2011). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol54/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. The Patriation and Quebec Veto References: The Supreme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution 2011 CanLIIDocs 443 Peter H. Russell* I. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA’S ROLE IN CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS Several times in Canada’s history the turbulent waters of constitu- tional politics have roared up to the Supreme Court, when for a moment the political gladiators in a constitutional struggle put down their armour, don legal robes and submit their claims to the country’s highest court. September 1981 was surely such a moment. Indeed, it is difficult to find any other constitutional democracy whose highest court has been called upon to render such a crucial decision in the midst of a mega constitutional struggle over the future of the country. -

The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy

51 The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy Yan Campagnolo* La légitimité politique du secret ministériel La legitimidad política del secreto ministerial A legitimidade política do segredo ministerial 内阁机密的政治正当性 Résumé Abstract Dans le système de gouvernement In the Westminster system of re- responsable de type Westminster, les sponsible government, constitutional conventions constitutionnelles protègent conventions have traditionally safe- traditionnellement le secret des délibéra- guarded the secrecy of Cabinet proceed- tions du Cabinet. Dans l’ère moderne, où ings. In the modern era, where openness l’ouverture et la transparence sont deve- and transparency have become funda- nues des valeurs fondamentales, le secret mental values, Cabinet secrecy is now ministériel est désormais perçu avec scep- looked upon with suspicion. The justifi- ticisme. La justification et la portée de la cation and scope of Cabinet secrecy re- règle font l’objet de controverses. Cet ar- main contentious. The aim of this article ticle aborde ce problème en expliquant les is to address this problem by explaining raisons pour lesquelles le secret ministériel why Cabinet secrecy is, within limits, es- est, à l’intérieur de certaines limites, essen- sential to the proper functioning of our tiel au bon fonctionnement de notre sys- system of government. Based on the rele- * Assistant Professor, Common Law Section, University of Ottawa. This article is based on the first chapter of a dissertation which was submitted in connection with fulfilling the requirements for a doctoral degree in law at the University of Toronto. The research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. For helpful comments on earlier versions, I am indebted to Kent Roach, David Dyzenhaus, Hamish Stewart, Peter Oliver and the anonymous reviewers of the Revue juridique Thémis. -

Union Charges Unfair Practices by KATHY CARNEY Grievances Are First Handled by an UBC Personnel Director John Employee's Immediate Superior

Plants against the sunrise .. UBC through the eye of an early bird ... a production of The Ubyssey's Dirk Visser. Union charges unfair practices By KATHY CARNEY grievances are first handled by an UBC personnel director John employee's immediate superior. McLean will meet Friday with If an agreement is not reached 17-year employee Jeanne Paul to at that stage, he said, the dispute discuss her job status at the goes up the university university. bureaucracy until it reaches the Paul was asked Sept. 30 for her department head and McLean for resignation from her job as 18 a final joint settlement. administrative assistant to the Vol. LIU, No. 13 VANCOUVER, B.C., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 14, 1971 «^p»> 228-2301 Lowe also said present benefits given to UBC employees would be dean of science faculty. approved, the personnel office employee who gets into the same discuss unionization. preserved in writing and that the The request was made after will attempt to find her another situation. Lowe said there has been a workers would have "an increased Paul attended a union organizing position within the university. The dispute between the union favorable response to the voice in salary and promotions." meeting Sept. 28 sponsored by Lowe warned that the union and the UBC administration organizing attempts. A meeting of university local 15 of the Office and will lay an unfair labor practices appears to stem from a major When asked to give reasons employees interested in Technical Employees Union. charge against UBC before the organizing drive on campus during why employees should join the unionization will be held at 5:30 OTEU spokesman Bill Lowe provincial Labor Relations Board the past two weeks. -

Programme 2004

38e CONGRES` ANNUEL DE L’ASSOCIATION CANADIENNE D’ECONOMIQUE´ 3 JUIN - 6 JUIN PROGRAMME 2004 38th ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE CANADIAN ECONOMICS ASSOCIATION JUNE 3 - JUNE 6 SECRETARY TREASURERS / SECRETAIRE-TR´ ESORIERS´ Gilles Paquet 1966-1981 Richard J. Arnott 1981-1984 Christopher Green 1984-1994 Michael Denny 1994-2004 Frances Woolley 2004- MANAGING EDITORS / DIRECTEURS Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue canadienne d’economique´ Ian M. Drummond, Andre´ Raynauld 1968-1969 A. Asimakopoulos, Andre´ Raynauld 1969-1970 A. Asimakopoulos, Robert Levesque´ 1971-1972 Bernard Bonin, Gideon Rosenbluth 1972-1973 G. C. Archibald, Bernard Bonin 1974 Gideon Rosenbluth 1975-1976 Stephan F. Kaliski 1977-1979 John F. Helliwell 1980-1982 Michael Parkin 1982-1987 Robin Boadway 1987-1993 Lorne Carmichael 1993-1994 Curtis Eaton 1994-1997 James Brander 1997-2001 Michel Poitevin 2001- MANAGING EDITORS / DIRECTEURS Canadian Public Policy / Analyse de Politiques John Vanderkamp 1975-1982 Anthony D. Scott 1982-1986 Kenneth Norrie 1986-1990 Nancy Olewiler 1991-1995 Charles M. Beach 1995-2002 Kenneth J. McKenzie 2002- Program Chair Barbara Spencer Organisatrice du congres` . (Univ. of British Columbia) Assistant to the Program Chair Maureen Church Assistante a` l’organisation . (University of Calgary) Information Technology Werner Antweiler Technologie informatique . (Univ. of British Columbia) Onsite Organizer Tom Barbiero Organisation locale . (Ryerson University) Note from the Organizer: This Conference Un mot de l’organisatrice: Ce congres` est vraiment is truly a group effort. First, I would like le resultat´ d’un travail collectif. D’abord, j’aimerais to thank all the participants, and particu- remercier tous les participants, particulierement` les larly those Chairs and Discussants who have presidents´ et presidentes´ de seances´ ainsi que les generously accepted assignments and have commentateurs et commentatrices. -

A Conversation with Martin Bradbury Wilk

Statistical Science 2010, Vol. 25, No. 2, 258–273 DOI: 10.1214/08-STS272 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2010 A Conversation with Martin Bradbury Wilk Christian Genest and Gordon Brackstone Abstract. Martin Bradbury Wilk was born on December 18, 1922, in Montr´eal, Qu´ebec, Canada. He completed a B.Eng. degree in Chemical Engineering in 1945 at McGill University and worked as a Research Engineer on the Atomic Energy Project for the National Research Council of Canada from 1945 to 1950. He then went to Iowa State College, where he completed a M.Sc. and a Ph.D. degree in Statistics in 1953 and 1955, respectively. After a one-year post-doc with John Tukey, he became Assistant Director of the Statistical Techniques Research Group at Princeton University in 1956–1957, and then served as Professor and Director of Research in Statistics at Rut- gers University from 1959 to 1963. In parallel, he also had a 14-year career at Bell Laboratories, Murray Hill, New Jersey. From 1956 to 1969, he was in turn Member of Technical Staff, Head of the Statistical Models and Meth- ods Research Department, and Statistical Director in Management Sciences Research. He wrote a number of influential papers in statistical methodology during that period, notably testing procedures for normality (the Shapiro– Wilk statistic) and probability plotting techniques for multivariate data. In 1970, Martin moved into higher management levels of the American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T) Company. He occupied various positions culminating as Assistant Vice-President and Director of Corporate Planning. In 1980, he returned to Canada and became the first professional statistician to serve as Chief Statistician. -

History of the Business Development Bank of Canada

History of the Business Development Bank of Canada The FBDB period (1975-1995) Donald Layne For the men and women who worked and work at Canada’s business development bank, FBDB and BDC Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec and Library and Archives Canada Title: History of the Business Development Bank of Canada: The FBDB period (1975-1995) Issued also in French under title: Histoire de la Banque de développement du Canada : La période BFD (1975-1995) ISBN 978-0-9953184-4-1 Published by the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC). All rights reserved. Printed in Canada. Also available in electronic format. In the event of any discrepancies between the English and French versions, the English version shall prevail. Legal deposit – Library and Archives Canada, 2016 Cover picture: Stock Exchange Tower, Montreal. BDC’s Head Office was located here from 1969 to 1997. Table of Contents Preface 06 Chapter 1 The genesis 09 Chapter 2 Creating FBDB 15 Chapter 3 Early days at FBDB 23 Chapter 4 On the eve of the great recession 40 Chapter 5 Cost recovery Part I 45 Chapter 6 SBFR & a new mandate for FBDB 58 Chapter 7 Cost recovery Part II 71 Chapter 8 Rock bottom 82 Chapter 9 Rebuilding 94 Chapter 10 Working with government 114 Chapter 11 Treasury ops 126 Chapter 12 Shocks to the system 138 Chapter 13 Another recession 149 Chapter 14 Information technology @ FBDB/BDC 169 Chapter 15 Start of a new era 190 Chapter 16 The BDC act 207 Chapter 17 Mandate change begets culture change 215 Appendix 1 Members of the boards of directors 234 Appendix 2 Contributors 236 6 Preface This book provides a history of the Business Development Bank of Canada during the period 1975 to 1995. -

Commercializing Canadian Airport, Port and Rail Governance - 1975 to 2000

Changing Course: Commercializing Canadian Airport, Port and Rail Governance - 1975 to 2000 By Mark Douglas Davis, B.Sc. (Hons.), M.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Policy Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Mark Douglas Davis Abstract This thesis examines the historical public policy circumstances surrounding the Government of Canada’s decision to commercialize Canadian National (CN) Railways, as well as federal airports and ports over the period 1975 to 2000. Its focus is on testing one specific empirical hypothesis: That the commercialization of federal airport and port assets between 1975 and 2000 occurred primarily due to: (i) federal government concerns over the growing size of the national debt and deficit; and (ii) the emergence of the neoliberal ideology in Canada and its growing influence throughout federal policy making, as witnessed by the swift 1995 privatization of CN Railways. In particular, this thesis considers the role and influence of various policy factors, such as efficiencies, governance challenges, organizational cultures, stakeholder behaviours, ideological pressures, and political realities encountered by senior federal transportation bureaucrats and the political leadership during this period. The selection of CN Railways, airports, and ports also provides a window into Transport Canada’s repeated attempts at developing an integrated and multi-modal national transportation policy. This thesis conducts a rigorous, forward-looking deductive analysis using a meso institutional framework to examine the interactions of the major micro and macro circumstances surrounding federal transportation commercialization. The three modal case studies apply the meso framework to each unique case with special consideration of the context and causality of each major reform. -

Coleman Chap

The Project on Trends:The Project on Trends: An Introduction S1 An Introduction WILLIAM D. COLEMAN Department of Political Science McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario n recent years, the rapid pace of change has put hence its relationship to the development of civil Isignificant pressure on the policy capacity of society was also examined. (David Cameron/Janice governments. Governments worldwide are finding Stein, University of Toronto) that they do not have adequate knowledge to respond to the challenges brought about by rapid technologi- North American integration. Although this theme is cal advances and the forces of globalization. a very old one in Canadian political and social life, Strengthening the policy capacity of governments this research was to take a broad look at aggregate lies in part in strengthening the policy research economic performance, more general indicators of process to produce the knowledge that governments the quality of life, the way Canadians are governed, need. Toward this end, in July 1996, the Clerk of and on culture broadly defined. In each of these the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet es- areas, several key questions were to be addressed. tablished the Policy Research Initiative (PRI). Its What is different about North American integration task was to develop a research strategy to help today, if anything? What have these recent changes Canada prepare for the public policy challenges of meant for things Canadians care about? What is the coming years. The Project on Trends built upon likely to happen to North American integration in the PRI’s efforts by engaging Canada’s academic the next decade? What can we do to preserve and community. -

Nerves of Iron Alumni Ironmen and Women

SPRING 2012 Nerves of Iron Alumni Ironmen and Women The Science of Suds Gaming Goes Global Bill Waiser on the Chilkoot Trail live & learn Centre for Continuing & Distance Education Brad started his career in the heart of Canada’s Parliament and now works for the Associate Vice- President, Information and Communications Technology. In his spare time, you’ll find him waxing show cars. He recently took our Business Writing and Grammar Workout to help polish his skills outside the garage. Brad Flavell 2007: BA History & Philosophy (U of S) 2006-07: VP Academic (USSU) 2004-06: Member of Student Council (Arts & Science Students’ Union) Each year, many University of Saskatchewan alumni, like Brad, take CCDE classes. Whether you want to enhance your career or explore your creativity, our programs are flexible—allowing you to maintain life-balance as you fulfil your educational goals. Work toward your certificate or degree from anywhere in the world. Learn a new language or take courses for personal interest and professional development. We have programs for everyone from all walks of life—from birth to seniors. To learn more visit ccde.usask.ca or call 306.966.5539. ccde.usask.ca CCDE-MISC-11052-DIVERTAS.indd 1 11-11-30 1:32 PM SPRING 2012 | CONTENTS inside this issue 12 Nerves of Iron Three alumni reflect on what drives them to compete in Ironman triathalons 2 In conversation with Dean Peter Stoicheff 4 News briefs 6 A Toolkit for Treatment | by John Lagimodiere (BA‘06) After struggling with substance abuse, Jenny Gardipy is now part of the solution -

Debates of the Senate

CANADA Debates of the Senate 3rd SESSION . 40th PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 147 . NUMBER 39 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, June 16, 2010 ^ THE HONOURABLE NOËL A. KINSELLA SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: D'Arcy McPherson, National Press Building, Room 906, Tel. 613-995-5756 Publications Centre: David Reeves, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 613-947-0609 Published by the Senate Available from PWGSC ± Publishing and Depository Services, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0S5. Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 803 THE SENATE Wednesday, June 16, 2010 The Senate met at 1:30 p.m., the Speaker in the chair. I would be remiss if I did not highlight Michael Pitfield's valuable contribution to our shared community of Ottawa, most Prayers. notably with the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, where he served as a member of the board for many years, including as its chair. Seven years ago, a chair in cardiac surgery was established SENATORS' STATEMENTS at the University of Ottawa in Senator Pitfield's name. It is a sad coincidence that both Senator Pitfield and Senator Keon retired from this place this spring. TRIBUTES As is well known, honourable senators, Senator Pitfield is the THE HONOURABLE P. MICHAEL PITFIELD, P.C. honorary Chair of the Parkinson's Society of Canada, a position that is no doubt tremendously meaningful as he has waged a The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I received notice personal fight against this dreaded disease for some time. It must earlier today from the Leader of the Government who requests, be difficult for Senator Pitfield to want to contribute as much as pursuant to rule 22(10), that the time provided for the ever to the work of this chamber but to have that desire tempered consideration of Senators' Statements be extended today for the by physical constraints.