Of the Privy Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPEN Federalism INTERPRETATIONS, SIGNIFICANCE Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Open Federalism : Interpretations, Significance

OPEN Federalism INTERPRETATIONS, SIGNIFICANCE Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Open federalism : interpretations, significance. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-1-55339-187-6 ISBN-10: 1-55339-187-X 1. Federal government—Canada. 2. Canada—Politics and government—21st century. I. Queen’s University (Kingston, Ont.). Institute of Intergovernmental Relations II. Title. JL27.O64 2006 320.471 C2006-905478-9 © Copyright 2006 Contents Preface v Sean Conway Contributors vii 1. Making Federalism Work 1 Richard Simeon 2. Open Federalism and Canadian Municipalities 7 Robert Young 3. Il suffisait de presque rien: Promises and Pitfalls of Open Federalism 25 Alain Noël 4. The Two Faces of Open Federalism 39 Peter Leslie 5. Open Federalism: Thoughts from Alberta 67 Roger Gibbins 6. Open Federalism and Canada’s Economic and Social Union: Back to the Future? 77 Keith G. Banting Preface Canada’s new Conservative government has a short list of priority policies, and it is moving quickly to fulfil the campaign promises made about them. But another theme in the Conservative campaign of 2005/06, and in the par- ty’s pronouncements since its formation, is that of “open federalism.” This attractive slogan may represent a new stance toward the other levels of gov- ernment, and the provinces in particular. But much about open federalism is unclear. What does the concept mean? Is it distinctive, and if so, how is it different from previous models of Canadian federalism? What does it mean in theory, and what are its practical implications for Canadian public policy- making and the operation of intergovernmental relations? To address these questions, the Institute of Intergovernmental Relations engaged several experts to bring different perspectives to bear in exploring the concept of open federalism. -

Finding Aid No. MSS2443 Maxwell Yalden Fonds

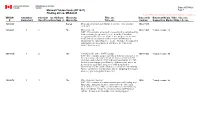

Date: 2017-03-21 Maxwell Yalden fonds (R11847) Page 1 Finding aid no. MSS2443 Report: Y:\APP\Impromptu75\Mikan\Reports\Description_Reports\finding_aids_&_subcontainers.imr MIKAN Container File/Item Cr. file/item Hierarchy Title, etc Date of/de Extent or Media / Dim. / Access # Contenant Dos./PièceDos./item cr. Hiérarchie Titre, etc création Support ou Média / Dim. / Accès 3684860 Series Department of External Affairs [textual record, graphic 1960-1989 material] 3684863 1 1 File Disarmament 1960-1963 Textual records / 10 S&C : File consists of records created and accumulated by Yalden during the period he served on the Canadian delegation to the Geneva Conference on disarmament in 1960 and the department's Disarmament Division in Ottawa for the following three years. Includes background information on disarmament and notes by Yalden on Soviet disarmament. 3684870 1 2 File Canada and France NATO Europe 1964-1967 Textual records / 90 S&C : File consists of material when Yalden was posted at the Canadian embassy in Paris as 1st secretary in 1963 and then counsellor in 1965 and return to Ottawa in 1967. Includes material prepared for the Ambassador, notes on French Foreign Policy, notes by Yalden and other documents relating to the European economic community. Notes, comments, memoranda, drafts, outgoing messages and excerpts from printed material. 3684874 1 3 File Miscelleneous memos 1968 Textual records / 90 S&C : File consists of administration material relating to a long-range program for travel abroad by the Governor General Jules Léger when Yalden was special advisor to Marcel Cadieux, Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs. Includes memoranda, letter and proposal. -

Hill Times, Health Policy Review, 17NOV2014

TWENTY-FIFTH YEAR, NO. 1260 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, NOVEMBER 17, 2014 $4.00 HEARD ON THE HILL BUZZ NEWS HARASSMENT Artist paints Queen, other prominent MPs like ‘kings, queens in their people, wants a national portrait gallery little domains,’ contribute to ‘culture of silence’: Clancy BY LAURA RYCKEWAERT “The combination of power and testosterone often leads, unfortu- n arm’s-length process needs nately, to poor judgment, especially Ato be established to deal in a system where there has been with allegations of misconduct no real process to date,” said Nancy or harassment—sexual and Peckford, executive director of otherwise—on Parliament Hill, Equal Voice Canada, a multi-par- say experts, as the culture on tisan organization focused on the Hill is more conducive to getting more women elected. inappropriate behaviour than the average workplace. Continued on page 14 NEWS HARASSMENT Campbell, Proctor call on two unnamed NDP harassment victims to speak up publicly BY ABBAS RANA Liberal Senator and a former A NDP MP say the two un- identifi ed NDP MPs who have You don’t say: Queen Elizabeth, oil on canvas, by artist Lorena Ziraldo. Ms. Ziraldo said she got fed up that Ottawa doesn’t have accused two now-suspended a national portrait gallery, so started her own, kind of, or at least until Nov. 22. Read HOH p. 2. Photograph courtesy of Lorena Ziraldo Liberal MPs of “serious person- al misconduct” should identify themselves publicly and share their experiences with Canadians, NEWS LEGISLATION arguing that it is not only a ques- tion of fairness, but would also be returns on Monday, as the race helpful to address the issue in a Feds to push ahead on begins to move bills through the transparent fashion. -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

The Patriation and Quebec Veto References: the Supreme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution 2011 Canliidocs 443 Peter H

The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 54 (2011) Article 3 The aP triation and Quebec Veto References: The Supreme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution 2011 CanLIIDocs 443 Peter H. Russell Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Citation Information Russell, Peter H.. "The aP triation and Quebec Veto References: The uS preme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution." The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference 54. (2011). http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/sclr/vol54/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The uS preme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. The Patriation and Quebec Veto References: The Supreme Court Wrestles with the Political Part of the Constitution 2011 CanLIIDocs 443 Peter H. Russell* I. THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA’S ROLE IN CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS Several times in Canada’s history the turbulent waters of constitu- tional politics have roared up to the Supreme Court, when for a moment the political gladiators in a constitutional struggle put down their armour, don legal robes and submit their claims to the country’s highest court. September 1981 was surely such a moment. Indeed, it is difficult to find any other constitutional democracy whose highest court has been called upon to render such a crucial decision in the midst of a mega constitutional struggle over the future of the country. -

HT-EM Logos Stacked(4C)

EXCLUSIVE POLITICAL COCOVERAGE:OVVEERARAGGE: NNEWS,REMEMBERING FEATURES, AND ANALYSISLYSISS INSIDEINNSSIDIDE ACCESS TO HILL TRANSPORTATION POLICY BRIEFING PP. 19-33 JEAN LAPIERRE P. 10 INFORMATION P. 14 CLIMBERS P.41 TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR, NO. 1328 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, APRIL 4, 2016 $5.00 NEWS SYRIAN REFUGEES NEWS NDP ‘Very, very Wernick planning to stick NDP policy few’ Syrian convention refugees came around PCO for a while, ‘one for the to Canada push on for ‘nimbleness and ages,’ many from refugee eager to vote camps: CBSA offi cial Bolduc agility’ in public service on Mulcair’s leadership BY ABBAS RANA “Very, very few” of the BY LAURA RYCKEWAERT thousands of Syrian refugees Privy Council who have come to Canada came Clerk Michael More than 1,500 NDP members from refugee camps and most had Wernick says will attend the party’s policy con- been living in rented apartments his current vention in Edmonton this week to in Syria’s neighbouring countries, priorities include help shape the NDP’s future. a senior CBSA offi cial told creating a public Many are eager to see a review Parliament in February. service that has vote on NDP Leader Tom Mulcair’s Conservatives are now accusing ‘nimbleness leadership and there’s much talk the federal government of convey- and agility’ so about the direction of the party and ing a false perception to Canadians it can meet its “soul,” after its crushing defeat that refugees were selected from the needs of a in the last federal election. refugee camps. But the government ‘busy, ambitious NDP analyst Ian Capstick says it has never said all Syrian government that said the event will be “one for the wants to do a lot ages.” Continued on page 35 in it’s mandate, but I think this Continued on page 34 would be true had we been NEWS SENATE dealing with a blue government NEWS PUBLIC SERVICE or an orange Sen. -

Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy

Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy Annual Report 2019–20 2 munk school of global affairs & public policy About the Munk School Table of Contents About the Munk School ...................................... 2 Student Programs ..............................................12 Research & Ideas ................................................36 Public Engagement ............................................72 Supporting Excellence ......................................88 Faculty and Academic Directors .......................96 Named Chairs and Professorships....................98 Munk School Fellows .........................................99 Donors ...............................................................101 1 munk school of global affairs & public policy AboutAbout the theMunk Munk School School About the Munk School The Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy is a leader in interdisciplinary research, teaching and public engagement. Established in 2010 through a landmark gift by Peter and Melanie Munk, the School is home to more than 50 centres, labs and teaching programs, including the Asian Institute; Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies; Centre for the Study of the United States; Centre for the Study of Global Japan; Trudeau Centre for Peace, Conflict and Justice and the Citizen Lab. With more than 230 affiliated faculty and more than 1,200 students in our teaching programs — including the professional Master of Global Affairs and Master of Public Policy degrees — the Munk School is known for world-class faculty, research leadership and as a hub for dialogue and debate. Visit munkschool.utoronto.ca to learn more. 2 munk school of global affairs & public policy About the Munk School About the Munk School 3 munk school of global affairs & public policy 2019–20 annual report 3 About the Munk School Our Founding Donors In 2010, Peter and Melanie Munk made a landmark gift to the University of Toronto that established the (then) Munk School of Global Affairs. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

Deputy Ministers And'politicization in the Government of Canada: Lessons Learned from the 2006-2007 Conservative Transition

DEPUTY MINISTERS AND'POLITICIZATION IN THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA: LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE 2006-2007 CONSERVATIVE TRANSITION by SHANNON LEIGH WELLS B.A (Hons) Dalhousie University, 2005 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Political Science) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2007 © Shannon Leigh Wells, 2007 Abstract This thesis analyses the 2006-07 Conservative transition in the Government of Canada by asking the following: is there evidence of overt partisan politicization of the deputy ministers during this transition? Significantly, there is no evidence of overt politicization. Harper has not forced departure of incumbent deputy ministers, nor has he appointed a significant number of known partisan allies from outside the public service. Instead, Harper has retained the overwhelming majority of deputy ministers who served the previous Liberal government. However, the 2006-07 transition also suggests considerable lateral career mobility of deputy ministers within the highest levels of government. The thesis argues that lateral mobility is explained by the "corporate" governance structure in the government of Canada, according to which deputy ministers are expected to identify with the government's broad policy goals and mobilize support for them. High degrees of lateral mobility during the Conservative transition provide evidence to suggest that a potentially rigid bureaucratic system can be made responsive to the policy priorities of a new government without compromising the professional norms of a non-partisan, career public service. ii Table of Contents Abstract ii Table of Contents > iii List of Tables. '. ...iv Acknowledgements '. -

2009 2008 2007 Operational Budget1 2,579 2,629 2,663 Expenses2 2,460 2,474 2,485 Operational Budget Over Expenses 119 155 178

Founded in 1972, the Institute for Research Board of Directors on Public Policy is an independent, national, nonprofi t organization. Janice MacKinnon, Chair (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan) Graham Scott, Vice-Chair (Toronto, Ontario) IRPP seeks to improve public policy in Canada by generating research, providing insight and Peter Aucoin (Halifax, Nova Scotia) sparking debate that will contribute to the public Ian Clark (Toronto, Ontario) policy decision-making process and strengthen Jim Dinning (Calgary, Alberta) the quality of the public policy decisions made by Mary Lou Finlay (Toronto, Ontario) Canadian governments, citizens, institutions and Ann Fitz-Gerald (Shrivenham, Wiltshire, UK) organizations. Frederick Gorbet (Toronto, Ontario) Antonia Maioni (Montreal, Quebec) IRPP’s independence is assured by an endowment John Manley (Ottawa, Ontario) fund established in the early 1970s. Barbara McDougall (Toronto, Ontario) Anne McLellan (Edmonton, Alberta) Jacques Ménard (Montreal, Quebec) David Pecaut (Toronto, Ontario) Martha Piper (Vancouver, British Columbia) Guy Saint-Pierre (Montreal, Quebec) Bernard Shapiro (Montreal, Quebec) Gordon Smith (Victoria, British Columbia) Paul Tellier (Montreal, Quebec) Kent Weaver (Washington, DC, USA) Wanda Wuttunee (Winnipeg, Manitoba) FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS OF OPERATING FUND (In thousands of dollars) The IRPP’s operations have run at a surplus for the last three years. 2009 2008 2007 Operational budget1 2,579 2,629 2,663 Expenses2 2,460 2,474 2,485 Operational budget over expenses 119 155 178 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS OF ENDOWMENT FUND (In thousands of dollars) 2009 2008 2007 Total year-end market value 31,055 38,633 42,159 1Operational budget consists of investment income approved for operations, prior year’s surplus, revenue from publications and other revenue. -

THE DECLINE of MINISTERIAL ACCOUNTABILITY in CANADA by M. KATHLEEN Mcleod Integrated Studies Project Submitted to Dr.Gloria

THE DECLINE OF MINISTERIAL ACCOUNTABILITY IN CANADA By M. KATHLEEN McLEOD Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr.Gloria Filax in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta Submitted April 17, 2011 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. ii Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 The Westminster System of Democratic Government ................................................................... 3 Ministerial Accountability: All the Time, or Only When it is Convenient? ................................... 9 The Richard Colvin Case .................................................................................................................. 18 The Over-Arching Power of the Prime Minister ............................................................................ 24 Michel Foucault and Governmentality ............................................................................................ 31 Governmentality .......................................................................................................................... 31 Governmentality and Stephen Harper ............................................................................................ 34 Munir Sheikh and the Long Form Census ....................................................................................... -

The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy

51 The Political Legitimacy of Cabinet Secrecy Yan Campagnolo* La légitimité politique du secret ministériel La legitimidad política del secreto ministerial A legitimidade política do segredo ministerial 内阁机密的政治正当性 Résumé Abstract Dans le système de gouvernement In the Westminster system of re- responsable de type Westminster, les sponsible government, constitutional conventions constitutionnelles protègent conventions have traditionally safe- traditionnellement le secret des délibéra- guarded the secrecy of Cabinet proceed- tions du Cabinet. Dans l’ère moderne, où ings. In the modern era, where openness l’ouverture et la transparence sont deve- and transparency have become funda- nues des valeurs fondamentales, le secret mental values, Cabinet secrecy is now ministériel est désormais perçu avec scep- looked upon with suspicion. The justifi- ticisme. La justification et la portée de la cation and scope of Cabinet secrecy re- règle font l’objet de controverses. Cet ar- main contentious. The aim of this article ticle aborde ce problème en expliquant les is to address this problem by explaining raisons pour lesquelles le secret ministériel why Cabinet secrecy is, within limits, es- est, à l’intérieur de certaines limites, essen- sential to the proper functioning of our tiel au bon fonctionnement de notre sys- system of government. Based on the rele- * Assistant Professor, Common Law Section, University of Ottawa. This article is based on the first chapter of a dissertation which was submitted in connection with fulfilling the requirements for a doctoral degree in law at the University of Toronto. The research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. For helpful comments on earlier versions, I am indebted to Kent Roach, David Dyzenhaus, Hamish Stewart, Peter Oliver and the anonymous reviewers of the Revue juridique Thémis.