The Capability Approach and Human Development: Some Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Capability Approach an Interdisciplinary Introduction

The Capability Approach An Interdisciplinary Introduction Ingrid Robeyns Version August 14th, 2017 Draft Book Manuscript Not for further circulation, please. Revising will start on September 22nd, 2017. Comments welcome, E: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Why the capability approach? ................................................................................. 5 1.2 The worries of the sceptics ....................................................................................... 7 1.3 A yardstick for the evaluation of prosperity and progress ........................... 9 1.4 Scope and development of the capability approach ...................................... 13 1.5 A guide to the reader ................................................................................................ 16 2 Core ideas and the framework .......................................................................... 18 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 18 2.2 A preliminary definition of the capability approach ..................................... 20 2.3 The capability approach versus capability theories ...................................... 24 2.4 The many modes of capability analysis ............................................................. 26 2.5 The modular view of the capability approach ................................................ -

Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Oman HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices -

The Capability Approach and the Right to Education for Persons with Disabilities

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2018, Volume 6, Issue 1, Pages 29–39 DOI: 10.17645/si.v6i1.1193 Article Equality of What? The Capability Approach and the Right to Education for Persons with Disabilities Andrea Broderick Department of International and European Law, Maastricht University, 6211 LH Maastricht, The Netherlands; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 29 September 2017 | Accepted: 27 December 2017 | Published: 26 March 2018 Abstract The right to education is indispensable in unlocking other substantive human rights and in ensuring full and equal partici- pation of persons with disabilities in mainstream society. The cornerstone of Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities seeks to ensure access to inclusive education for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others as well as the full development of human potential. Since the adoption of the Convention, there has been much theorising about inclusive education; however, there has been little focus on the meaning of equal- ity in the context of the right to education for persons with disabilities. The capability approach, developed by Amartya Sen and further refined by Martha Nussbaum, focuses on ensuring equality and developing human potential. It is of- ten viewed as a tool that can be used to overcome the limitations of traditional equality assessments in the educational sphere, which only measure resources and outcomes. This article explores whether the capability approach can offer new insights into the vision of educational equality contained in the Convention and how that vision can be implemented at the national level. -

The Capability Approach: Its Development, Critiques and Recent Advances

An ESRC Research Group The Capability Approach: Its Development, Critiques and Recent Advances GPRG-WPS-032 David A. Clark Global Poverty Research Group Website: http://www.gprg.org/ The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged. The work was part of the programme of the ESRC Global Poverty Research Group. 1 The Capability Approach: Its Development, Critiques and Recent Advances By David A. Clark* Over the last decade Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach (CA) has emerged as the leading alternative to standard economic frameworks for thinking about poverty, inequality and human development generally. In countless articles and several books that tackle a range of economic, social and ethical questions (beginning with the Tanner Lecture ‘Equality of What?’ delivered at Stanford University in 1979), Professor Sen has developed, refined and defended a framework that is directly concerned with human capability and freedom (e.g. Sen, 1980; 1984; 1985; 1987; 1992; 1999). From the outset Sen acknowledged strong connections with Adam Smith’s (1776) analysis of ‘necessities’ and living conditions and Karl Marx’s (1844) concern with human freedom and emancipation. Later Sen (1993, p.46) recognised that ‘the most powerful conceptual connections’ (which he initially failed to appreciate) relate to Aristotle’s theory of ‘political distribution’ and his analysis of eudaimonia – ‘human flourishing’ (see Nussbaum, 1988; 1990). While the roots of the CA can be traced back to Aristotle, Classical Political Economy and Marx, it is possible to identify more recent links. For example, Sen often notes that Rawls’s Theory of Justice (1971) and his emphasis on ‘self-respect’ and access to primary goods has ‘deeply influenced’ the CA (Sen, 1992, p.8). -

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report Chile Introduction This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the first Human Development Report and of the introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was published to steer discussions about development progress away from GPD towards a measure that genuinely “counts” for people’s lives. Introduced by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) thirty years ago to provide a simple measure of human progress – built around people’s freedoms to live the lives they want to - the HDI has gained popularity with its simple yet comprehensive formula that assesses a population’s average longevity, education, and income. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in providing a more comprehensive set of measurements that capture other critical dimensions of human development. To respond to this call, new measures of aspects of human development were introduced to complement the HDI and capture some of the “missing dimensions” of development such as poverty, inequality and gender gaps. Since 2010, HDRO has published the Inequality-adjusted HDI, which adjusts a nation’s HDI value for inequality within each of its components (life expectancy, education and income) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index that measures people’s deprivations directly. Similarly, HDRO’s efforts to measure gender inequalities began in the 1995 Human Development Report on gender, and recent reports have included two indices on gender, one accounting for differences between men and women in the HDI dimensions, the other a composite of inequalities in empowerment and well-being. -

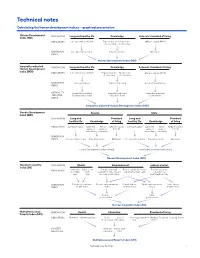

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female -

Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice: the Capability Approach Re-Examined

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Robeyns, Ingrid Book — Published Version Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined Provided in Cooperation with: Open Book Publishers Suggested Citation: Robeyns, Ingrid (2017) : Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined, ISBN 978-1-78374-459-6, Open Book Publishers, Cambridge, http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0130 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182376 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice The Capability Approach Re-Examined INGRID ROBEYNS To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/682 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. -

The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics Theorizing, Analyzing, and Transforming Capitalism Tae-Hee Jo, Lynne Chester, Carlo D'ippoliti

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 27 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics Theorizing, Analyzing, and Transforming Capitalism Tae-Hee Jo, Lynne Chester, Carlo D'Ippoliti The social surplus approach Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315707587.ch3 Nuno Ornelas Martins Published online on: 28 Jul 2017 How to cite :- Nuno Ornelas Martins. 28 Jul 2017, The social surplus approach from: The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics, Theorizing, Analyzing, and Transforming Capitalism Routledge Accessed on: 27 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315707587.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 The social surplus approach Historical origins and present state Nuno Ornelas Martins Introduction For classical political economists, the social surplus is the part of production that is not necessary for the reproduction of the existing social system. -

The Human Development Index

32 ADOPTION The Human Development Index – a better indicator for success? When faced with the complexity of the Sustainable Development Goals, we need a digestible, precise way of measuring progress By Hayley Lashmar, to a country’s wealth, or even GDP per framework swells in complexity – with 17 United Nations Association – UK capita, which tells us something about an goals, 169 targets and even more indicators individual’s means but nothing about their – there is also a need for a simple way to roduced by the UN Development life outcomes. measure progress. Over a 15-year timeframe, Programme in 1990, the firstHuman Of course, the HDI has its limitations. the HDI will do a better job than GDP of PDevelopment Report outlined a new It omits several factors that can have a capturing what progress is being achieved. approach to development, focused on people significant influence on quality of life, such It reflects a more nuanced understanding and their opportunities rather than economic as environmental degradation. Industrial of human development while being simple growth alone. The Human Development pollution and deforestation, for example, enough to remain inclusive: unlike other Index (HDI) was introduced as a way to can lead to complex health problems more complex indices, the HDI is based on quantify this approach. Nearly 30 years (e.g. lymphatic filariasis) or mental health data that is likely to have been collected in later, the Sustainable Development Goals conditions that do not necessarily have an many countries for a number of years. have rekindled discussions on how we impact on mortality rates but which can Despite this, most countries still use measure progress. -

Human Development Report 2016

Human Development Report 2016 Human Development for Everyone Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Human Development Report 2016 | Human Development for Everyone for Development Human | Report 2016 Development Human The 2016 Human Development Report is the latest in the series of global Human Development Reports published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) since 1990 as independent, analytically and empirically grounded discussions of major development issues, trends and policies. Additional resources related to the 2016 Human Development Report can be found online at http://hdr.undp.org, including digital versions of the Report and translations of the overview in more than 20 languages, an interactive web version of the Report, a set of background papers and think pieces commissioned for the Report, interactive maps and databases of human development indicators, full explanations of the sources and methodologies used in the Report’s composite indices, country profiles and other background materials as well as previous global, regional and national Human Development Reports. The 2016 Report and the best of Human Development Report Office content, including publications, data, HDI rankings and related information can also be accessed on Apple iOS and Human Development AndroidReport smartphones2016 via a new and easy to use mobile app. Human Development for Everyone The cover reflects the basic message that human development is for everyone—in the human development journey no one can be left out. Using an abstract approach, the cover conveys three fundamental points. First, the upward moving waves in blue and whites represent the road ahead that humanity has to cover to ensure universal human development. -

Re-Framing Inclusive Education Through the Capability Approach: an Elaboration of the Model of Relational Inclusion

122 Global Education Review 3(3) Re-framing Inclusive Education Through the Capability Approach: An Elaboration of the Model of Relational Inclusion Maryam Dalkilic The University of British Columbia Jennifer A. Vadeboncoeur The University of British Columbia Abstract Scholars have called for the articulation of new frameworks in special education that are responsive to culture and context and that address the limitations of medical and social models of disability. In this article, we advance a theoretical and practical framework for inclusive education based on the integration of a model of relational inclusion with Amartya Sen’s (1985) Capability Approach. This integrated framework engages children, educators, and families in principled practices that acknowledge differences, rather than deficits, and enable attention to enhancing the capabilities of children with disabilities in inclusive educational environments. Implications include the development of policy that clarifies the process required to negotiate capabilities and valued functionings and the types of resources required to permit children, educators, and families to create relationally inclusive environments. Keywords inclusive education, children with disabilities, inclusive education environments, relational inclusion, Capability Approach, medical model of disability, social model of disability, International Classification of Functionings (ICF) Introduction difference between these two models in the way Originally formulated by Sen (1985, 1992) as an they “explain the interplay -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Heinicke, Philipp Working Paper The evolution of the capability approach or Sen's quest for an informational base Discussion Papers, No. 6/2010 Provided in Cooperation with: Witten/Herdecke University, Faculty of Management and Economics Suggested Citation: Heinicke, Philipp (2010) : The evolution of the capability approach or Sen's quest for an informational base, Discussion Papers, No. 6/2010, Universität Witten/Herdecke, Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaft, Witten This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/49942 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in