Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Capability Approach an Interdisciplinary Introduction

The Capability Approach An Interdisciplinary Introduction Ingrid Robeyns Version August 14th, 2017 Draft Book Manuscript Not for further circulation, please. Revising will start on September 22nd, 2017. Comments welcome, E: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Why the capability approach? ................................................................................. 5 1.2 The worries of the sceptics ....................................................................................... 7 1.3 A yardstick for the evaluation of prosperity and progress ........................... 9 1.4 Scope and development of the capability approach ...................................... 13 1.5 A guide to the reader ................................................................................................ 16 2 Core ideas and the framework .......................................................................... 18 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 18 2.2 A preliminary definition of the capability approach ..................................... 20 2.3 The capability approach versus capability theories ...................................... 24 2.4 The many modes of capability analysis ............................................................. 26 2.5 The modular view of the capability approach ................................................ -

The Capability Approach and the Right to Education for Persons with Disabilities

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2018, Volume 6, Issue 1, Pages 29–39 DOI: 10.17645/si.v6i1.1193 Article Equality of What? The Capability Approach and the Right to Education for Persons with Disabilities Andrea Broderick Department of International and European Law, Maastricht University, 6211 LH Maastricht, The Netherlands; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 29 September 2017 | Accepted: 27 December 2017 | Published: 26 March 2018 Abstract The right to education is indispensable in unlocking other substantive human rights and in ensuring full and equal partici- pation of persons with disabilities in mainstream society. The cornerstone of Article 24 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities seeks to ensure access to inclusive education for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others as well as the full development of human potential. Since the adoption of the Convention, there has been much theorising about inclusive education; however, there has been little focus on the meaning of equal- ity in the context of the right to education for persons with disabilities. The capability approach, developed by Amartya Sen and further refined by Martha Nussbaum, focuses on ensuring equality and developing human potential. It is of- ten viewed as a tool that can be used to overcome the limitations of traditional equality assessments in the educational sphere, which only measure resources and outcomes. This article explores whether the capability approach can offer new insights into the vision of educational equality contained in the Convention and how that vision can be implemented at the national level. -

The Capability Approach: Its Development, Critiques and Recent Advances

An ESRC Research Group The Capability Approach: Its Development, Critiques and Recent Advances GPRG-WPS-032 David A. Clark Global Poverty Research Group Website: http://www.gprg.org/ The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged. The work was part of the programme of the ESRC Global Poverty Research Group. 1 The Capability Approach: Its Development, Critiques and Recent Advances By David A. Clark* Over the last decade Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach (CA) has emerged as the leading alternative to standard economic frameworks for thinking about poverty, inequality and human development generally. In countless articles and several books that tackle a range of economic, social and ethical questions (beginning with the Tanner Lecture ‘Equality of What?’ delivered at Stanford University in 1979), Professor Sen has developed, refined and defended a framework that is directly concerned with human capability and freedom (e.g. Sen, 1980; 1984; 1985; 1987; 1992; 1999). From the outset Sen acknowledged strong connections with Adam Smith’s (1776) analysis of ‘necessities’ and living conditions and Karl Marx’s (1844) concern with human freedom and emancipation. Later Sen (1993, p.46) recognised that ‘the most powerful conceptual connections’ (which he initially failed to appreciate) relate to Aristotle’s theory of ‘political distribution’ and his analysis of eudaimonia – ‘human flourishing’ (see Nussbaum, 1988; 1990). While the roots of the CA can be traced back to Aristotle, Classical Political Economy and Marx, it is possible to identify more recent links. For example, Sen often notes that Rawls’s Theory of Justice (1971) and his emphasis on ‘self-respect’ and access to primary goods has ‘deeply influenced’ the CA (Sen, 1992, p.8). -

Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice: the Capability Approach Re-Examined

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Robeyns, Ingrid Book — Published Version Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined Provided in Cooperation with: Open Book Publishers Suggested Citation: Robeyns, Ingrid (2017) : Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined, ISBN 978-1-78374-459-6, Open Book Publishers, Cambridge, http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0130 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182376 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.econstor.eu Wellbeing, Freedom and Social Justice The Capability Approach Re-Examined INGRID ROBEYNS To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/682 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. -

The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics Theorizing, Analyzing, and Transforming Capitalism Tae-Hee Jo, Lynne Chester, Carlo D'ippoliti

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 27 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics Theorizing, Analyzing, and Transforming Capitalism Tae-Hee Jo, Lynne Chester, Carlo D'Ippoliti The social surplus approach Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315707587.ch3 Nuno Ornelas Martins Published online on: 28 Jul 2017 How to cite :- Nuno Ornelas Martins. 28 Jul 2017, The social surplus approach from: The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics, Theorizing, Analyzing, and Transforming Capitalism Routledge Accessed on: 27 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315707587.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 The social surplus approach Historical origins and present state Nuno Ornelas Martins Introduction For classical political economists, the social surplus is the part of production that is not necessary for the reproduction of the existing social system. -

Re-Framing Inclusive Education Through the Capability Approach: an Elaboration of the Model of Relational Inclusion

122 Global Education Review 3(3) Re-framing Inclusive Education Through the Capability Approach: An Elaboration of the Model of Relational Inclusion Maryam Dalkilic The University of British Columbia Jennifer A. Vadeboncoeur The University of British Columbia Abstract Scholars have called for the articulation of new frameworks in special education that are responsive to culture and context and that address the limitations of medical and social models of disability. In this article, we advance a theoretical and practical framework for inclusive education based on the integration of a model of relational inclusion with Amartya Sen’s (1985) Capability Approach. This integrated framework engages children, educators, and families in principled practices that acknowledge differences, rather than deficits, and enable attention to enhancing the capabilities of children with disabilities in inclusive educational environments. Implications include the development of policy that clarifies the process required to negotiate capabilities and valued functionings and the types of resources required to permit children, educators, and families to create relationally inclusive environments. Keywords inclusive education, children with disabilities, inclusive education environments, relational inclusion, Capability Approach, medical model of disability, social model of disability, International Classification of Functionings (ICF) Introduction difference between these two models in the way Originally formulated by Sen (1985, 1992) as an they “explain the interplay -

Capabilities, Culture and Social Structure

This is a repository copy of Capabilities, culture and social structure. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/114624/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Jackson, W.A. orcid.org/0000-0001-5194-7307 (2005) Capabilities, culture and social structure. Review of Social Economy. pp. 101-124. ISSN 0034-6764 https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760500048048 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ CAPABILITIES, CULTURE AND SOCIAL STRUCTURE William A. Jackson Department of Economics and Related Studies, University of York, York YO10 5DD, UK Email: [email protected] Abstract Sen's capability approach has a culturally specific side, with capabilities influenced by social structures and institutions. Although Sen acknowledges this, he expresses his theory in individualistic terms and makes little allowance for culture or social structure. The present paper draws from recent social theory to discuss how the capability approach could be developed to give an explicit treatment of cultural and structural matters. -

The Capabilities Approach: a Future Alternative to Neoliberal Higher Education in the MENA Region

http://ijhe.sciedupress.com International Journal of Higher Education Vol. 7, No. 3; 2018 The Capabilities Approach: A Future Alternative to Neoliberal Higher Education in the MENA Region Ranya S. ElKhayat1 1 EdD student, School of Education, University of Glasgow, UK Correspondence: Ranya S. ElKhayat, EdD student, School of Education, University of Glasgow, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 4, 2018 Accepted: April 26, 2018 Online Published: May 1, 2018 doi:10.5430/ijhe.v7n3p36 URL: https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v7n3p36 Abstract This conceptual paper is a future study aiming to shed light on the current state of higher education in the MENA region. The neoliberal agenda for higher education in the region presents a form of education that is commodified, corporatized and focused on STEM rather than on humanities. The paper further speculates on the state of higher education in the near future under the same ideology. As an alternative, the study proposes the implementation of Martha Nussbaum’s Capabilities Approach. This approach is capable of re-balancing the tipped scale in the commodification of higher education and will serve in developing well-rounded individuals. The Capabilities Approach can reform higher education through critical thinking, liberal education, and attention to diversity. Keywords: capabilities approach, MENA, higher education, neo-liberalism 1. Introduction Higher education (HE) is beset with urgent issues in need of attention. One of the most compelling concerns is the state of HE in the neoliberal agenda. Neoliberalism, under the banner of globalization and the special regard to the knowledge society or the knowledge economy has created a higher education that is no longer functioning for the common good. -

Gross National Happiness and Beyond: a Micro Welfare Economics Approach”

“Gross National Happiness and Beyond: A micro welfare economics approach” Preface In the first international seminar on Gross National Happiness(GNH), my paper focussed on the development of macro model of GNH which started from in-country capital formation (positive side of foreign direct investment has been taken as the trigger) leading to Gross National Product as the starting point for achieving Balanced Equitable Development, Cultural and Heritage Promotion and Preservation, Good Governance, and Environment Conservation. Thus the approach was more from the macro side and a top down approach was followed. In this paper, which is written for presentation in the Second International Seminar on GNH in Halifax, Canada,I would like to approach the sustainable development concept of GNH from micro level using a bottom- up approach. For this purpose, the paper would draw upon the Capability Approach as propagated by Nobel laureate Professor Amartya Sen and related liberal theory of justice philosophy of Martha C. Nussbaum and a host of works by other authors in this topic of interest. The paper will also establish the linkage between social capital and capability approach for arriving at GNH. With a survey on the scope and choices available to Bhutanese people and capability achieved by them vis-à-vis United kingdom, a developed state. Acknowledgement The author would like to thank GPI Atlantic, Canada and Canadian International Development Agency for their partial funding and invitation. The Author would also like to thank Mr Kipchu Tshering, Managing Director, Bhutan National Bank for his support and all other colleagues in the Bank who helped the survey possible. -

The Political Economy of Northern Regional Development

The Political Economy of Northern Regional Development Vol. I Gorm Winther, Gérard Duhaime, Jack Kruse, Chris Southcott, Hans Aage, Ivar Jonsson, Lyudmila Zalkind, Iulie Aslaksen, Solveig Glomsröd, Anne Ingeborg Myhr, Hugo Reinert, Svein Mathiesen, Erik Reinert, Joan Nymand Larsen, Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, Andrée Caron, Birger Poppel, Jón Haukur Ingimundarson (in order of appearance) TemaNord 2010:521 The Political Economy of Northern Regional Development Vol. I TemaNord 2010:521 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2016-0 Print: Scanprint as Cover photo: Gorm Winther Copies: 430 Printed on environmentally friendly paper .This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/publications This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers. But the con- tents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views, policies or recommendations of the Nordic Council of Ministers. “This project was conducted as part of the International Polar Year 2007–2008, which was sponsored by the International Council for Science and the World. Meteorological Organisation. The project was cofinanced by the Commission for Social Scientific Research in Greenland, the Department for Planning, Innovation and Management, Denmarks Technical University, the Department for Environmental, Social and Spatial Change, University of Roskilde and the Department of Development and Planning, University of Aalborg.” Printed in Denmark Nordic Council of Ministers Nordic Council Store Strandstræde 18 Store Strandstræde 18 DK-1255 Copenhagen K DK-1255 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 Fax (+45) 3396 0202 Fax (+45) 3311 1870 www.norden.org Nordic co-operation Nordic co-operation is one of the world’s most extensive forms of regional collaboration, involv- ing Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and three autonomous areas: the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. -

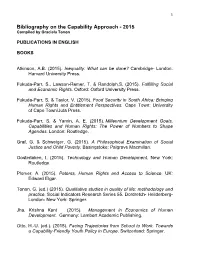

Bibliography on the Capability Approach - 2015 Compiled by Graciela Tonon

1 Bibliography on the Capability Approach - 2015 Compiled by Graciela Tonon PUBLICATIONS IN ENGLISH BOOKS Atkinson, A.B. (2015). Inequality: What can be done? Cambridge- London: Harvard University Press. Fukuda-Parr, S., Lawson-Remer, T. & Randolph,S. (2015). Fulfilling Social and Economic Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Fukuda-Parr, S. & Taylor, V. (2015). Food Security in South Africa: Bringing Human Rights and Entitlement Perspectives. Cape Town: University of Cape Town/Juta Press. Fukuda-Parr, S. & Yamin, A. E. (2015). Millennium Development Goals, Capabilities and Human Rights: The Power of Numbers to Shape Agendas. London: Routledge. Graf, G. & Schweiger, G. (2015). A Philosophical Examination of Social Justice and Child Poverty. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Oosterlaken, I. (2015). Technology and Human Development. New York: Routledge. Plomer, A. (2015). Patents, Human Rights and Access to Science. UK: Edward Elgar. Tonon, G. (ed.) (2015). Qualitative studies in quality of life: methodology and practice. Social Indicators Research Series 55. Dordretch- Heilderberg- London- New York: Springer. Jha, Krishna Kant (2015). Management in Economics of Human Development. Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing. Otto, H.-U. (ed.). (2015). Facing Trajectories from School to Work. Towards a Capability-Friendly Youth Policy in Europe. Switzerland: Springer. 2 BOOK CHAPTERS Dawson, N. (2015). Bringing context to poverty in rural Rwanda: Added value and challenges of mixed method approaches. In K. Roelen & L. Camfield (Eds.), Mixed Methods Research in Poverty and Vulnerability: Sharing Ideas and Learning Lessons. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Drydyk, J. (2015). Empowerment, Agency, and Power. In E. Palmer (Ed.), Gender Justice and Development: Vulnerability and Empowerment, vol. II. (pp. 5-18). New York: Routledge. -

Distributive Ecological Justice on a Shared Earth

Life in Common: Distributive Ecological Justice on a Shared Earth A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Anna Wienhues School of Social Sciences Blank page 2 Contents Section Page List of Tables 4 Abstract 5 Lay Abstract 6 Declaration 7 Copyright Statement 8 Dedication 9 Acknowledgements 10 Introduction 12 1. Biocentric Ecological Justice in Context 29 Part 1 2. Common Habitation of the Earth: Justice and Ecological Space 53 3. Against Humanity’s ‘Original Ownership’ of the Earth 81 Part 2 4. The Capabilities Approach and Ecological Justice: A Critique 107 5. Sharing the Earth: A Biocentric Account of Ecological Justice 130 6. Biodiversity Loss: An Injustice? 160 Part 3 7. Sharing Ecological Space: Demands of Environmental and Ecological Justice 183 8. Just Conservation: Scarcity and the Half-Earth Proposal 221 Conclusion 254 Bibliography 262 75,723 words 3 List of Tables Table Page 1. Summary of the levels of scarcity and ecological and environmental justice demands 203 4 Abstract The University of Manchester Anna Wienhues Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Life in Common: Distributive Ecological Justice on a Shared Earth January 2018 This thesis lies in the overlap of environmental political theory and environmental ethics. More specifically, it focuses on the intersection between distributive ecological justice –justice to nature – and environmental justice – distributing environmental ‘goods’ between humans. Against the backdrop of the current sixth extinction crisis, I address the question of what constitutes a just usage of ecological space. I define ecological space as encompassing environmental resources, benefits provided by ecosystems and physical spaces and when considering its just usage I not only take into account claims to ecological space held by other humans but also the demands of justice with regards to nonhuman living beings such as animals and plants.