Human Development Report 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensions of Remarks E273 HON. FRANK PALLONE, JR. HON

March 7, 2018 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E273 unintended consequences. Many radio sta- Mr. Speaker, I sincerely hope that my col- Originally Convair Airfield, the 325-acre air- tions that are co-located on TV towers could leagues will join me in congratulating Dr. port was built by Consolidated-Vultee Aircraft be forced to shut down during spectrum relo- Masood Khatamee on receiving the Banou, Incorporated in September 1943. The space cation. With 670 radio stations possibly being Inc. Lifetime Achievement Award. This honor functioned as the test site for the Navy’s impacted, we must ensure our local radio sta- is truly deserving of this body’s recognition. Seawolf torpedo bombers, which were built at tions are protected in a process from which f the nearby Mack Trucks’ plant. Eighty-six they will receive no benefit. bombers were tested at the Convair facility, I appreciate the inclusion of section 603, PERSONAL EXPLANATION but the war concluded before any of the which makes funds available for radio broad- planes were commissioned for duty. casters to address this problem. This section HON. CARLOS CURBELO The City of Allentown purchased the gov- incorporates the fundamentals of the bill that OF FLORIDA ernment land on July 10, 1947, and in addition Representative GENE GREEN and I introduced IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES to the land, the government parted with in H.R. 3685, the Radio Consumer Protection Wednesday, March 7, 2018 Convair Airfield—valued at over $1 million—for Act. Our bipartisan bill established a radio pro- $1 under the condition that Allentown main- tection fund to reimburse impacted stations for Mr. -

China's Propaganda in the United States During World War II

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 248 514 CS 208 471 AUTHOR Tsang, Kuo-jen - TITLE China's Propaganda in the United States during World War II. PUB DATE Aug 84 NOTE 44p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (67th, Gainesville, FL, August 5-8, . , 1984). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Speeches /Conference Papers (150) \N, EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Content Analysis; Cultural Images; Foreign`Countries; information Sources; *Media Research; News Reporting; *Propaganda; *Public Opinion; War; World History IDENTIFIERS *China; *World War II ABSTRACT Drawing data from a variety of sources, a study was undertaken to place China's propaganda activities in the United States during World War II into a historical perspective. Results showed that China's propaganda effortsconsisted of official and unofficial activities and activities directed toward overseas Chinese. The official activities were carried out by the Chinese News Service and its branch offices in various American cities under the direction of the Ministry of Information's International Department in Chungking. The unofficial activities Were carried out by both Chinese and Americans, including missionaries, business people, and newspaper reporters, and the activities ditected toward the overseas Chinese in the United States were undertaken for the purpose of collecting money and arousing patriotism. The propaganda program fell four phases, the first beginning with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and directed at exposing Japanese atrocities. The second phase began with the withdrawal of the Chinese central government to inner China in late 1937, continued until the beginning of the European war in 1939, and concentrated on economic and political interests. -

Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience

Human Development Report 2014 Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience Explanatory note on the 2014 Human Development Report composite indices Oman HDI values and rank changes in the 2014 Human Development Report Introduction The 2014 Human Development Report (HDR) presents the 2014 Human Development Index (HDI) (values and ranks) for 187 countries and UN-recognized territories, along with the Inequality-adjusted HDI for 145 countries, the Gender Development Index for 148 countries, the Gender Inequality Index for 149 countries, and the Multidimensional Poverty Index for 91 countries. Country rankings and values of the annual Human Development Index (HDI) are kept under strict embargo until the global launch and worldwide electronic release of the Human Development Report. It is misleading to compare values and rankings with those of previously published reports, because of revisions and updates of the underlying data and adjustments to goalposts. Readers are advised to assess progress in HDI values by referring to table 2 (‘Human Development Index Trends’) in the Statistical Annex of the report. Table 2 is based on consistent indicators, methodology and time-series data and thus shows real changes in values and ranks over time, reflecting the actual progress countries have made. Small changes in values should be interpreted with caution as they may not be statistically significant due to sampling variation. Generally speaking, changes at the level of the third decimal place in any of the composite indices -

2016 Case List

FRONT COVER 1 3 PEN INTERNATIONAL CHARTER The PEN Charter is based on resolutions passed at its International Congresses and may be summarised as follows: PEN affirms that: 1. Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals. 2. In all circumstances, and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion. 3. Members of PEN should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world. 4. PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong, as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world towards a more highly organised political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restraint, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends. Membership of PEN is open to all qualified writers, editors and translators who subscribe to these aims, without regard to nationality, ethnic origin, language, colour or religion. -

Determinants of Multidimensional Poverty Index of Niger State, Nigeria

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 1 1 , No. 14, Contemporary Business and Humanities Landscape Towards Sustainability. 2021, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2021HRMARS Determinants of Multidimensional Poverty Index of Niger State, Nigeria Musa Mohammed, Rossazana Ab-Rahim To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v11-i14/8532 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v11-i14/8532 Received: 29 November 2020, Revised: 25 December 2020, Accepted: 18 January 2021 Published Online: 30 January 2021 In-Text Citation: (Mohammed & Ab-Rahim, 2021) To Cite this Article: Mohammed, M., & Ab-Rahim, R. (2021). Determinants of Multidimensional Poverty Index of Niger State, Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 11(14), 95– 108. Copyright: © 2021 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Special Issue: Contemporary Business and Humanities Landscape Towards Sustainability, 2021, Pg. 95 – 108 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 95 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 1 1 , No. 14, Contemporary Business and Humanities Landscape Towards Sustainability. -

The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 17th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 13th, 1:30 PM - 3:00 PM The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Myrice, Erin, "The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa" (2015). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 2. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2015/004/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. The Impact of the Second World War on the Decolonization of Africa Erin Myrice 2 “An African poet, Taban Lo Liyong, once said that Africans have three white men to thank for their political freedom and independence: Nietzsche, Hitler, and Marx.” 1 Marx raised awareness of oppressed peoples around the world, while also creating the idea of economic exploitation of living human beings. Nietzsche created the idea of a superman and a master race. Hitler attempted to implement Nietzsche’s ideas into Germany with an ultimate goal of reaching the whole world. Hitler’s attempted implementation of his version of a ‘master race’ led to one of the most bloody, horrific, and destructive wars the world has ever encountered. While this statement by Liyong was bold, it held truth. The Second World War was a catalyst for African political freedom and independence. -

Measuring the Inequality of Well-Being: the Myth Of

Measuring the Inequality of Well-being: The Myth of “Going beyond GDP” By Lauri Peterson Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Thomas Fetzer Word count: 15,987 CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract The last decades have seen a surge in the development of indices that aim to measure human well-being. Well-being indices (such as the Human Development Index, the Genuine Progress Indicator and the Happy Planet Index) aspire to go beyond the standard growth-based economic definitions of human development (“go beyond GDP”), however, this thesis demonstrates that this is not always the case. The thesis looks at the methods of measuring the distributional aspects of human well-being. Based on the literature five clusters of inequality are developed: economic inequality, educational inequality, health inequality, gender inequality and subjective inequality. These types of distribution have been recognized to receive the most attention in the scholarship of (in)equality measurement. The thesis has discovered that a large number of well-being indices are not distribution- sensitive (do not account for inequality) and indices which are distribution-sensitive primarily account for economic inequality. Only a few indices, such as the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index, the Gender Inequality Index, the Global Gender Gap and the Legatum Prosperity Index are sensitive to non-economic inequality. The most comprehensive among the distribution-sensitive well-being indices that go beyond GDP is the Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index which accounts for the inequality of educational and health outcomes. -

Measuring Human Development and Human Deprivations Suman

Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI) Oxford Department of International Development Queen Elizabeth House (QEH), University of Oxford OPHI WORKING PAPER NO. 110 Measuring Human Development and Human Deprivations Suman Seth* and Antonio Villar** March 2017 Abstract This paper is devoted to the discussion of the measurement of human development and poverty, especially in United Nations Development Program’s global Human Development Reports. We first outline the methodological evolution of different indices over the last two decades, focusing on the well-known Human Development Index (HDI) and the poverty indices. We then critically evaluate these measures and discuss possible improvements that could be made. Keywords: Human Development Report, Measurement of Human Development, Inequality- adjusted Human Development Index, Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty JEL classification: O15, D63, I3 * Economics Division, Leeds University Business School, University of Leeds, UK, and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford, UK. Email: [email protected]. ** Department of Economics, University Pablo de Olavide and Ivie, Seville, Spain. Email: [email protected]. This study has been prepared within the OPHI theme on multidimensional measurement. ISSN 2040-8188 ISBN 978-19-0719-491-13 Seth and Villar Measuring Human Development and Human Deprivations Acknowledgements We are grateful to Sabina Alkire for valuable comments. This work was done while the second author was visiting the Department of Mathematics for Decisions at the University of Florence. Thanks are due to the hospitality and facilities provided there. Funders: The research is covered by the projects ECO2010-21706 and SEJ-6882/ECON with financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology, the Junta de Andalucía and the FEDER funds. -

Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems

Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Prof. Paczkowski Rutgers University Fall, 2007 Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 1 / 87 Part I Assignments Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 2 / 87 Assignments W. Baumol, et al. Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism Available at http://www.yalepresswiki.org/ Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 3 / 87 Assignments Research and learn as much as you can about the following: Real GDP Human Development Index Gini Coefficient Corruption Index World Population Growth Human Poverty Index Quality of Life Index Reporters without Borders Be prepared for a second Group Teach on these after the midterm: October 24 Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 4 / 87 Part II Introduction Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 5 / 87 Comparing Economic Systems How do we compare economic systems? We previously noted the many qualitative ways of comparing economic systems { organization, incentives, etc What about the quantitative? Potential quantitative measures might include Real GDP level and growth Population level and growth Income and wealth distribution Major financial and industrial statistics Indexes of freedom and corruption These measures should tell a story The story is one of economic performance Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 6 / 87 Comparing Economic Systems (Continued) Economic performance is multifaceted Judging how an economic system performs, we can look at broad topics or issues such as.. -

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing note for countries on the 2020 Human Development Report Chile Introduction This year marks the 30th Anniversary of the first Human Development Report and of the introduction of the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI was published to steer discussions about development progress away from GPD towards a measure that genuinely “counts” for people’s lives. Introduced by the Human Development Report Office (HDRO) thirty years ago to provide a simple measure of human progress – built around people’s freedoms to live the lives they want to - the HDI has gained popularity with its simple yet comprehensive formula that assesses a population’s average longevity, education, and income. Over the years, however, there has been a growing interest in providing a more comprehensive set of measurements that capture other critical dimensions of human development. To respond to this call, new measures of aspects of human development were introduced to complement the HDI and capture some of the “missing dimensions” of development such as poverty, inequality and gender gaps. Since 2010, HDRO has published the Inequality-adjusted HDI, which adjusts a nation’s HDI value for inequality within each of its components (life expectancy, education and income) and the Multidimensional Poverty Index that measures people’s deprivations directly. Similarly, HDRO’s efforts to measure gender inequalities began in the 1995 Human Development Report on gender, and recent reports have included two indices on gender, one accounting for differences between men and women in the HDI dimensions, the other a composite of inequalities in empowerment and well-being. -

To What Extent Was World War Two the Catalyst Or Cause of British Decolonisation?

To what extent was World War Two the catalyst or cause of British Decolonisation? Centre Number: FR042 Word Count: 3992 Words Did Britain and her colonies truly stand united for “Faith, King and Empire” in 1920, and to what extent was Second World War responsible for the collapse of this vast empire? Cover Picture: K.C. Byrde (1920). Empire of the Sun [online]. Available at: http://worldwararmageddon.blogspot.com/2010/09/empire-of-sun.html Last accessed: 27th January 2012 Table of Contents Abstract Page 2 Introduction Page 3 Investigation Page 4 – Page 12 • The War Caused Decolonisation in Page 4 – Page 7 African Colonies • The War acted as a Catalyst in an Page 7 – Page 8 international shift against Imperialism • The War Slowed down Decolonisation in Page 8 – Page 10 Malaya • The War Acted as a Catalyst with regard Page 10 – Page 11 to India • The Method of British Imperialism was Page 11 – Page 12 condemned to fail from the start. Conclusion Page 13 Bibliography Page 14 – Page 15 1 Abstract This question answered in this extended essay is “Was World War Two the catalyst or the cause of British Decolonisation.” This is achieved by analysing how the war ultimately affected the British Empire. The British presence in Africa is examined, and the motives behind African decolonisation can be attributed directly to the War. In areas such as India, once called the ‘Jewel of the British Empire,’ it’s movement towards independence had occurred decades before the outbreak of the War, which there acted merely as a Catalyst in this instance. -

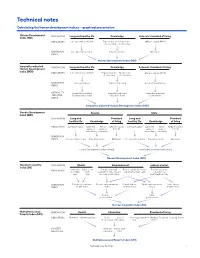

Technical Notes

Technical notes Calculating the human development indices—graphical presentation Human Development DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Index (HDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy index Education index GNI index INDEX Human Development Index (HDI) Inequality-adjusted DIMENSIONS Long and healthy life Knowledge A decent standard of living Human Development Index (IHDI) INDICATORS Life expectancy at birth Expected years Mean years GNI per capita (PPP $) of schooling of schooling DIMENSION Life expectancy Years of schooling Income/consumption INDEX INEQUALITY- Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted Inequality-adjusted ADJUSTED life expectancy index education index income index INDEX Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI) Gender Development Female Male Index (GDI) DIMENSIONS Long and Standard Long and Standard healthy life Knowledge of living healthy life Knowledge of living INDICATORS Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita Life expectancy Expected Mean GNI per capita years of years of (PPP $) years of years of (PPP $) schooling schooling schooling schooling DIMENSION INDEX Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Life expectancy index Education index GNI index Human Development Index (female) Human Development Index (male) Gender Development Index (GDI) Gender Inequality DIMENSIONS Health Empowerment Labour market Index (GII) INDICATORS Maternal Adolescent Female and male Female