First Peoples Students in Higher Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018-2019 Table of Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Chair and the Director General ........................................................................................................................ 2 Mission Statement ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 College Governance ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Code of Ethics ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Strategic Plan 2015-2020 ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Highlights of 2018-2019 .............................................................................................................................................................................................................10 Celebrating Achievements ..................................................................................................................................................................................................18 -

Participating Universities and Colleges: Acadia University Algoma University Algonquin College Ambrose University Assiniboine C

Participating universities and colleges: Acadia University Cégep de Thetford Algoma University Cégep de Trois-Rivières Algonquin College Cégep de Victoriaville Ambrose University Cégep du Vieux Montréal Assiniboine Community College Cégep régional de Lanaudière à Joliette Bishop’s University Centennial College Booth University College Centre d'études collégiales de Montmagny Brandon University Champlain College Saint-Lambert Brescia University College Collège Ahuntsic Brock University Collège d’Alma Cambrian College Collège André-Grasset Camosun College Collège Bart Canadian Mennonite University Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne Canadore College Collège Boréal Cape Breton University Collège Ellis Capilano University Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf Carleton University Collège Laflèche Carlton Trail College Collège LaSalle Cégep de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue Collège de Maisonneuve Cégep de Baie-Comeau Collège Montmorency Cégep de Chicoutimi College of the North Atlantic Cégep de Drummondville Collège O’Sullivan de Montréal Cégep Édouard-Montpetit Collège O’Sullivan de Québec Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles College of the Rockies Cégep Gérald-Godin Collège TAV Cégep de Granby Collège Universel Gatineau Cégep Heritage College Collégial du Séminaire de Sherbrooke Cégep de Jonquière Columbia Bible College Cégep de Lévis Concordia University Cégep Marie-Victorin Concordia University of Edmonton Cégep de Matane Conestoga College Cégep de l’Outaouais Confederation College Cégep La Pocatière Crandall University Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup Cumberland College Cégep Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu Dalhousie University Cégep de Saint-Jérôme Dalhousie University Agricultural Campus Cégep de Sainte-Foy Douglas College Cégep de St-Félicien Dumont Technical Institute Cégep de Sept-Îles Durham College Cégep de Shawinigan École nationale d’administration publique Cégep de Sorel-Tracy (ENAP) Cégep St-Hyacinthe École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) Cégep St-Laurent Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Cégep St. -

Mcgill Master Plan

DRA MASTERPLAN 2019 1 CREDITS + ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS McGill contributors: The Campus Planning and Development Office wishes to thank: Executive Director, McGill Teaching and Learning Services Campus Planning and Development Office (CPDO): Cameron Charlebois Facilities Management and Ancillary Services Manager, Master and Campus Planning (CPDO): Anna Bendix The McGill Office of Sustainability Senior Campus Planners The Office of the Dean of Libraries (Master and Campus Planning team, CPDO): Adam Dudeck (project coordinator) The Office of the Dean, Macdonald Campus Maxime Gagnon Kakwiranoron Cook, Special Advisor, Indigenous Initiatives Janelle Kasperski, Indigenous Education Advisor Project support (CPDO): Allan Vicaire, Associate Director, Student Services Director Stakeholder Relations: Dicki Chhoyang Space Data Administrator: Ian Tattersfield McGill Graphics, Communications and External Relations Manager, Special Projects and Planning: Geneviève Côté Senior Campus Planner (Development): Paul Guenther Joan Busquets, urban planner, BAU Barcelona, whose urban design study created for McGill in 2017 greatly informed this plan. Approved by the Board of Governors on May 23, 2019 MESSAGE FROM THE PRINCIPAL AND VICE-CHANCELLOR Dear Members of the McGill Community, At McGill University, we pride ourselves on having As we approach our third century, McGill is com- beautiful and vibrant campuses, both at Macdonald mitted to providing opportunities that open doors, and nestled in the heart of downtown Montreal. Our leading research that will change lives, fostering campuses are more than just a space for our class- innovation, and ensuring that our students are fu- rooms, libraries, labs, arts and sports facilities, and ture-ready. Our surroundings must therefore create student residences; they bring together all of these an environment that breeds collaboration, bold elements to create an ecosystem for growth and ideas, and critical thinking. -

2014 Program

SALTISE 3RD ANNUAL CONFERENCE 3E CONFÉRENCE ANNUELLE S Bridging knowing how A with knowing why L Bâtir un pont entre T savoir pourquoi et I savoir comment S E June 12, 2014 | 12 juin 2014 http://www.saltise.ca/conference-2014/ [email protected] SALTISE Annual Conference | 2014 Program Table of Contents Table des matières Welcome from Richard Filion ................................................. 4 Mot Bienvenue de Richard Fillon ........................................... 4 Welcome from Robert Kavanagh ........................................... 5 Mot de Bienvenue de Robert Kavanagh ................................ 5 Information about SALTISE .................................................... 6 Informations sur SALTISE ........................................................ 6 Welcome from SALTISE .......................................................... 7 Mot de bienvenue de SALTISE ............................................... 7 Committees ............................................................................ 7 Comités .................................................................................. 7 Location of Events ............................................................. 8 - 9 Lieux des événements ....................................................... 8 - 9 Keynote Speakers ................................................................. 10 Conférenciers ....................................................................... 10 Program at a Glance .................................................... -

Annual Report 2016-2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Chair and the Director General ..................2 Mission Statement ..........................................................................................................................3 College Governance .....................................................................................................................4 Code of Ethics .........................................................................................................................................6 Strategic Plan 2015-2020 .......................................................................................................8 Highlights of 2016-2017 ......................................................................................................10 Celebrating Achievements ...........................................................................................18 About our Students ..................................................................................................................22 Enrolment in the Day Division .......................................................................22 DECs Granted ..........................................................................................................................23 Enrolment in Continuing Education .....................................................23 AECs Granted ...........................................................................................................................23 First Semester Overall Pass Rates -

Past Imperfect: Reflections on Memory September 10 -14, 2018 Dawson College

Humanities and Public Life Conference Past Imperfect: REFLECTIONS ON MEMORY September 10 -14, 2018 Dawson College Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, September 10th September 11th September 12th September 13th September 14th 8:30 – 9:45 a.m. Thoughts on Building Like a Hurricane: KEYNOTE Civic engagement a Common Memory Grappling with PRESENTATION – what it looks like, Across Cultural and the Past after 9/11, who gets to Historical Divides: the Colombian Conflict, A Closer Look participate, and what Muslim Philosophers and Katrina at Human Dignity forms of participation on Memory, Tradition are valued Gray Miles and Social Interaction and Translation Humanities Department, Catherine Richardson/ Rudayna Bahubeshi Michael Nafi Dawson College Kinewesquao Inspirit Foundation Humanities, Metis counsellor, Presentation Co-Sponsored Philosophy, and Religion, School of Social Work, with Dawson Peace Week John Abbott College Université de Montréal 10:00 – 11:15 a.m. The Unpast, “You know this: why Politicization and SPECIAL PLACE Narratives, our ‘actual’ form do I have to tell you Polarization? The (3T Theatre) Memory and Policing of memory all this if you already Influence of Mass From Ani Kouni Black Lives know it?”: Recaps, Media on American Dominique Scarfone to Cowboys and Robyn Maynard the binge-watch, and Views and Voting Indians: Increasing Psychology Department, the Iliad Behavior Presentation Co-Sponsored Université de Montréal our understanding of with Dawson Peace Week Lynn Kozak Elizabeth Fischer cultural appropriation History and Martin Elizabeth Fast Classics Studies, School of Public Affairs, Applied Human McGill University American University Sciences, MOderatOR Concordia University Chris Bourne Politics Department, Dawson College 11:30 – 12:45 p.m. -

Simonsehayek Education

SimonSehayek education 2015– Ph.D. Physics McGill University, Montreal present Supervisor: Paul Wiseman 2013–2015 M.Sc. Physics McGill University, Montreal Thesis: Refinements and extensions of correlation techniques applied to fluorescence microscopy (thesis link) Supervisor: Paul Wiseman 2010–2013 B.Sc. Joint Hons. Mathematics and Physics McGill University, Montreal Graduated with First Class Honours 2008–2010 D.E.C. Science John Abbott College, Montreal research experience 2013– McGill University Montreal, Canada present Research Assistantship My main focus of research is developing ensemble autocorrelation approaches for rapidly extracting biologically relevant parameters from fluorescence image series. Summer Weizmann Institute of Science Rehovot, Israel 2012 Undergraduate Summer Research Project Research in complex fluid dynamics as a summer student. publications 1. Sehayek, S.; Gidi, Y.; Glembockyte, V.; Brandão, H. B.; François, P.; Cosa, G.; Wiseman, P. W. A High-Throughput Image Correlation Method for Rapid Analysis of Fluorophore Photoblinking and Photobleaching Rates. ACS Nano Article ASAP. DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.9b06033 2. Mikolajewicz, N.; Sehayek, S.; Wiseman, P. W.; Komarova, S. V. Transmission of Me- chanical Information by Purinergic Signaling. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 2009-2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.04.012 posters 2019 BPS Poster Baltimore, MD Beating Nyquist Limits for the Measurement of Fluorophore Blinking Rates using Image Correlation and Camera Detection Abstract DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.11.3057 2016 McGill Physics Outreach Montreal, Canada teaching & tutoring 2013–2018 McGill University Montreal, Canada Teaching Assistant Tasks included: lab demonstrations, grading, office hours, tutorials. From 2015–2018, I was a TA for biophysics course PHYS/BIOL 319 and had to create assignments, class notes, worksheets, exam questions and solutions. -

Programmes TIPSA Anglais.Indd

GUIDE TO TECHNICAL TRAINING IN ENGLISH GENERAL ADMISSION CONDITIONS In keeping with the College Education Regulations (CER), to be admitted to a program leading to a Diploma of College Studies (DCS), students must meet one of the following three conditions: 1. Have a Secondary School Diploma (SSD) A person who has a SSD, but who has not successfully completed the following subjects, must complete remedial studies during his or her college studies: • Secondary V Language of Instruction • Secondary V Second Language • Secondary IV Mathematics • Secondary IV Science and Technology or Technological and Scientifi c Applications • Secondary IV History and Citizenship Education A college may, however, grant conditional admission to a student who requires six credits or less to obtain his or her Sec- ondary School Diploma. The students must agree to obtain these credits during the fi rst term of his or her college studies. 2. Have a Diploma of Vocational Studies (DVS) A student who has a DVS must have also successfully completed the following subjects: • Secondary V Language of Instruction • Secondary V Second Language • Secondary IV Mathematics A college may, however, grant conditional admission to a student who has completed two out of three required subjects in addition to a DVS, and who agrees to complete the third subject during the fi rst term of his or her college studies. A student who has obtained a DVS is also eligible for admission to certain programs designated by the Minister. In this case, the student must meet certain conditions established for each program of study, in accordance with the vocational training program completed in secondary school. -

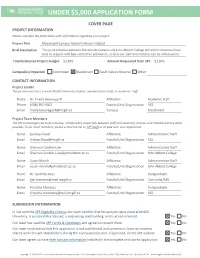

Under $5,000 Application Form

UNDER $5,000 APPLICATION FORM COVER PAGE PROJECT INFORMATION Please complete the fields below with information regarding your project. Project Title Macdonald Campus Native Pollinator Habitat Brief Description This joint initiative between Macdonald Campus and John Abbott College will aim to showcase how best to support wild bees and other pollinators, so that our staff and students can be ambassadors . Total Estimated Project Budget $2,876 Amount Requested from SPF $1,876 Campus(es) Impacted Downtown Macdonald Gault Nature Reserve Other CONTACT INFORMATION Project Leader This person must be a current McGill University student, administrative staff, or academic staff. Name Dr. Frieda Beauregard Affiliation Academic Staff Phone (438) 392-4902 Faculty/Unit/Organization AES Email [email protected] Campus Macdonald Project Team Members The SPF encourages you to be inclusive, collaborative (especially between staff and students), diverse, and interdisciplinary when possible. To list more members, please e-mail the list to SPF Staff to include with your application. Name Lindsay Flood Affiliation Administrative Staff Email [email protected] Faculty/Unit/Organization AES Name Shannon Coulter-Low Affiliation Administrative Staff Email [email protected] Faculty/Unit/Organization John Abbott College Name Susan Marsh Affiliation Administrative Staff Email [email protected] Faculty/Unit/Organization John Abbott College Name Dr. Gail MacInnis Affiliation Postgraduate Email [email protected] Faculty/Unit/Organization Concordia/AES Name Krisztina Mosdoss Affiliation Postgraduate Email [email protected] Faculty/Unit/Organization AES SUBMISSION INFORMATION In line with the SPF Eligibility Criteria, our team certifies that this project takes place at McGill University, is sustainability focused, is requesting seed funding, and is action oriented. -

The Lillian Robinson Scholars Program

The Lillian Robinson Scholars Program Lillian Robinson Dr. Lillian Robinson, a feminist scholar whose career spanned over 35 years, was Principal of the Simone de Beauvoir Institute, home of the first Women’s Studies program in Canada, from 2000 to 2006. She was widely recognized as one of the leading feminist theorists of the twentieth century, and her essays and books have inspired feminist scholarship around the world. Dr. Robinson was the author of the ground-breaking collections of essays on literature and culture, Sex, Class, and Culture (1978) and In the Canon’s Mouth: Dispatches from Culture Wars (1997); a chapbook of poetry, Robinson on the Woman Question (1975); Wonder Women: Feminisms and Superheroes (2004), a study of feminist superheroes and the comics; and a murder mystery, Murder Most Puzzling (1998). She was co-author of Feminist Scholarship: Kindling in the Groves of Academe (1984) and Night Market (1998), a book about the Thai sex trade. She also edited a four-volume reference book, Modern Women Writers (1996). Prior to joining the Concordia University faculty, Dr. Robinson taught at the State University of New York at Buffalo, the Sorbonne, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Hawaii, and East Carolina University. The Lillian Robinson Scholars program honours her memory by bringing distinguished Visiting Scholars to the Simone de Beauvoir Institute at Concordia to enhance the intellectual vitality of the institution. Program Information The Lillian Robinson Scholars Program is designed to attract a series of distinguished visiting scholars working on a range of feminist research topics to the Simone de Beauvoir Institute of Concordia University. -

John Abbott College

JOHN ABBOTT COLLEGE SPORTS Not the greatest week for John Abbot sports a couple ups and downs. The women’s Volleyball get third place in tournament. The women’s Basketball win 49-48 against Heritage College Hurricane, unfortunetly we loss for Women’s Hockey against rivals Dawson Blues Elimination from playoff contention for the Men’s Basketball A great weekend for Lacrosse, Rugby and Football read all about it on page 3 & 4! Cha Cha Real Smooth: Latin & Ballroom Dance Ballroom and latin dancing classes are coming to John Abbott College for the first time this winter. Starting February 1st, you can take the steps necessary to becoming the Casanova you’ve always dreamed of. Read more on the next page! FEBUARY FOOD DRIVE Women’s Hockey VS Dawson College Blues Are you JAC Alumni? Do you have a child or family member at John Abbott College? Do you hate the thought that there are students here on our campus that are hungry and need our help? You can make a difference. Don’t miss this event! You get the opportunity to help our students in need. The JAC Pantry will be there with food bins and a 50/50 raffle! No donation is too small. A bag of non-perishable food items or a monetary donation would make a world of difference! We can’t wait to see you there! Read more about our great activities on the next page! (514) 457-6610 [email protected] 21275 Lakeshore Dr, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, QC H9X 3L9 FEBUARY FOOD DRIVE Women’s Hockey VS Dawson College Blues Are you JAC Alumni? Do you have a child or family member at John Abbott College? Do you hate the thought that there are students here on our campus that are hungry and need our help? You can make a difference. -

Associate Director-University Safety & Head of Security Services: Pierre

Associate Director-University Safety & Head of Security Services: Pierre Barbarie Number of Staff Members: Downtown Campus Management Staff (10): Operations Manager, Systems Technology Supervisor, Supervisor, Investigations and Community Relations, Operations Administrator (Crime Prevention and Statistical Analysis), Operations Administrator (Security Operations Center), Operations Administrator (Special Events), Operations Administrator (Construction Projects), Operations Administrator (Agent Services), Information Liaison Officers. Agency Uniformed Personnel (65): 1 Captain, 1 Assistant Captain, 1 Senior Lieutenant, 4 Shift Supervisors, 1 Relations Patroller, 17 Patrollers, 8 Controllers, 32 Security Agents. Administrative and Technical Staff (5) Featured above are the Management, Administrative and Technical Team of McGill Security Services. IACLEA SPOTLIGHT: McGILL UNIVERSITY SECURITY SERVICES Number of Staff Members: Macdonald Campus Management Staff (2): Operations Manager, Operations Administrator (Security Systems) Agency Uniformed Personnel (30): 1 Captain, 4 Sergeants, 25 Security Agents. Total Staff on both Campuses (113) Macdonald (MAC) Campus Security Services delivers services and expertise relating to protection, prevention, response, guidance and information for the safety and security of people and assets of Macdonald campus and John Abbott College (JAC). There are approximately 2000 students at MAC and 7000 students at JAC. We have a combined population of roughly 10,000, 15 major buildings, on 650 hectares in a beautiful waterfront setting on the Western tip of the island of Montreal. Macdonald Campus is truly unique, located in the picturesque town of Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue. The IACLEA SPOTLIGHT: McGILL UNIVERSITY SECURITY SERVICES campus is spread over 1900 acres of land including a working farm, research facilities, an Arboretum and Ecomusuem that are patrolled by a team of dedicated security professionals.