An Anya-Centered Feminist Analysis of Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Sanctuary Theology in the Book of Exodus

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Summer 1986, Vol. 24, No. 2, 127-145. Copyright@ 1986 by Andrews University Press. SANCTUARY THEOLOGY IN THE BOOK OF EXODUS ANGEL MANUEL RODRIGUEZ Antillian College Mayaguez, Puerto Rico 00709 The book of Exodus is the first OT book that mentions the Israelite sanctuary. This book provides us not only with precise information with respect to the sanctuary's physical structure and furniture, but also with basic information on its significance. The present study proposes to take an overview of several important theological motifs that emerge in connection with the ancient Israelite sanctuary as portrayed in the book of Exodus. Although various of these aspects have already been noticed by other researchers, my hope herein is to bring together certain significant elements in such a way as to broaden our understanding of the ancient Hebrew concept of the meaning of the ancient Israelite sanctuary. At the outset, it is appropriate to state that the various ele- ments we shall consider all have a bearing upon, and contribute to, an overarching theological concern related to the OT sanctuary/ temple: namely, the presence of Yahweh. Moreover, the book of Exodus is foundational for a proper understanding of this basic motif, as it describes how the people of Israel were miraculously delivered from Egyptian slavery by Yahweh, and how, by his grace, they became a holy nation under his leadership. He entered into a covenant relationship with them, and gave them the precious gift of his own presence.' 'The theology of the presence of God is a very important one in the OT. -

Continuation on the Last Judgment

Continuation on the Last Judgment 1763 © 2009 Swedenborg Foundation This version was compiled from electronic files of the Standard Edition of the Works of Emanuel Swedenborg as further edited by William Ross Woofenden. Pagination of this PDF document does not match that of the corresponding printed volumes, and any page references within this text may not be accurate. However, most if not all of the numerical references herein are not to page numbers but to Swedenborg’s section numbers, which are not affected by changes in pagination. If this work appears both separately and as part of a larger volume file, its pagination follows that of the larger volume in both cases. This version has not been proofed against the original, and occasional errors in conversion may remain. To purchase the full set of the Redesigned Standard Edition of Emanuel Swedenborg’s works, or the available volumes of the latest translation (the New Century Edition of the Works of Emanuel Swedenborg), contact the Swedenborg Foundation at 1-800-355-3222, www.swedenborg.com, or 320 North Church Street, West Chester, Pennsylvania 19380. Contents 1. The last judgment has been accomplished (sections 1–7) 2. The state of the world and of the church before the last judgment and after it (8–13) 3. The last judgment on the reformed (14–31) Continuation on the spiritual world 4. The spiritual world (32–38) 5. The English in the spiritual world (39–47) 6. The Dutch in the spiritual world (48–55) 7. The Papists in the spiritual world (56–60) 8. -

UA 12 Steps 04072020

UA QUESTIONS Read step one out of the AA 12 and 12 then answer the questions. 1. What symptoms of underearning have you experienced or are you currently experiencing? (Hint: look at the symptoms list) 2. How have you tried to control or overcome underearning on your own efforts? 3. In what ways has your under earning defeated you...what did you do in response to this feeling of defeat? (Hint: Quit jobs, use credit cards, fight with co-workers) 4. How is underearning making your life unmanageable (Having no money, job or clients, debting, eviction) 5. How have you tried to make under earning work? (Hint: working 3 jobs, working overtime, cheating on the job) 6. What do you consider to be an underearning job or client? 7. How did you react to other people's prosperity around you and why? (Hint: Undercut them, criticize them, gossip about them, conspire against them, etc) 8. In what instances have you had a bad attitude about being an employee or a subordinate? How did you express this bad attitude? 9. In what instances have you slacked off on the job, disappointing supervisors, co-workers, family members or spouses? 10. How have you tried to top or outshine your co-workers in order to get a raise or promotion as a solution to your under earning? 11. In what instances did you manipulate others to do your work for you because you felt the work was beneath you. Read step two out of the AA 12 and 12 then answer the questions. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

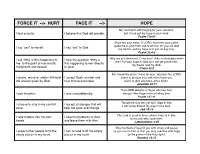

FORCE IT FACE IT HOPE Handout

FORCE IT --> HURT FACE IT --> HOPE My soul faints with longing for your salvation, ! I fear scarcity. I believe that God will provide. but I have put my hope in your word.! Psalm 119:81 Show me your ways, O LORD, teach me your paths; ! guide me in your truth and teach me, for you are God ! I say “yes” to myself. I say “yes” to God. my Savior, and my hope is in you all day long. ! Psalm 25:4-5 I ask “Why is this happening to I take the question “Why is Why are you downcast, O my soul? Why so disturbed within me? Put your hope in God, for I will yet praise him, ! me” to the point of narcissistic this happening to me” directly my Savior and my God.! martyrdom and despair. to God. Psalm 42:5 For I know the plans I have for you," declares the LORD, I ignore, mis-use, and/or withhold I accept God’s answer and "plans to prosper you and not to harm you, ! the answer given by God. trust Him to know best. plans to give you hope and a future.! Jeremiah 29:11 The LORD delights in those who fear him, ! I pick favorites. I love unconditionally. who put their hope in his unfailing love.! Psalm 147:11 Though he slay me, yet will I hope in him; ! I choose to stay in my comfort I accept challenges that will I will surely defend my ways to his face.! zone. help me grow and change. Job 13:15 The Lord is good to those whose hope is in him, ! I take matters into my own I take my problems to God to the one who seeks him; ! hands. -

Inside the Leaders of Tomorrow

NEWSLETTER | VOL. 2 INSIDE THE LEADERS OF TOMORROW MOVING INTO NEW HOMES RESIDENTS WORKING ON REBUILD FIRST BUILDING Wallace has been a resident of Sunnydale his whole life. In order GOING UP to qualify to work for Cahill on Parcel Q, he recently completed an eight-week training class. Welcome to the second move into the new homes. Our multilingual and issue of The Sunnydale multicultural staff are working in partnership Newsletter. So much is with Bay Area Legal Aid and the YMCA to happening on the ground provide one-on-one counseling to households that we barely have room for eviction prevention, so they can retain their to share all the highlights current apartments and qualify for relocation in this issue. On behalf of and later replacement housing. our staff, residents, and partners, we thank you for We are working tirelessly with residents to A LETTER making the redevelopment prepare them to move into their new homes FROM DOUG of Sunnydale a reality. We and renovated apartments within Sunnydale. SHOEMAKER, appreciate your support and Through a partnership with San Francisco’s PRESIDENT couldn’t do it without you. housing agencies, dozens of residents have already moved into new homes around the city, The most tangible sign of progress is including 23 families that chose to move into construction of the first Sunnydale replacement Mercy Housing’s recently completed Natalie 2 homes, which are halfway finished and Gubb Commons near the Salesforce Transbay scheduled to open in fall of 2019. Development Terminal. of the first new homes at Sunnydale is being led by our partners, Related Companies of Last but not least, with funding from our 2017 California. -

Satan's Sibling - Poems

Poetry Series Satan's Sibling - poems - Publication Date: 2008 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Satan's Sibling(15/03/1990) I am a poetry enthusiast with a variety of poetry styles. Some are love poems, some are hate poems. But I guess that love and hate are the basis of life, Aren't they? (My motto for life is 'There is no God, he is a figment of our imagination. There is no Karma, we punish ourselves. No destiny, we choose our own path. No freedom. We are bound by our own laws. For now.) www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 1 Million Years Bc (Lyrics) They're calling me, the creatures of the nigh, Beautiful music, Animal instincts survived, the serpent tongue, so ancient before the dawn of time, Spread throughout the ages, On the blood of mankind. I've seen it all. From grace man falls, Babylon, curse of all creation, Winged serpent of the pit, Monstrosity. Ten thousand centuries ago, Cast down from heaven, To pillage below, The serpents eye, Still watching for it's easy prey, Feed upon the hopeless, the weak and afraid. I've seen it all. From grace men fall, Babylon, curse of all creation. Winged serpent of the pit, Monstrosity. 1 million yeasr bc x3 Satan's Sibling www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 8 Line Poem (Lyrics) The tactful cactus by your window Surveys the prairie of your room The mobile spins to its collision Clara puts her head between her paws They've opened shops down West side Will all the cacti find a home But the key to the city Is in the sun that pins the branches to the sky Satan's Sibling www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 A Desirable Complication I sit here in anguish, Silently suffering. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 2010 "Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett University of Nebraska at Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Burnett, Tamy, ""Just a Girl": The Community-Centered Cult Television Heroine, 1995-2007" (2010). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 by Tamy Burnett A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Specialization: Women‟s and Gender Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Kwakiutl L. Dreher Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2010 “JUST A GIRL”: THE COMMUNITY-CENTERED CULT TELEVISION HEROINE, 1995-2007 Tamy Burnett, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2010 Adviser: Kwakiutl L. Dreher Found in the most recent group of cult heroines on television, community- centered cult heroines share two key characteristics. The first is their youth and the related coming-of-age narratives that result. -

Living Clean the Journey Continues

Living Clean The Journey Continues Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Living Clean Approval Draft Copyright © 2011 by Narcotics Anonymous World Services, Inc. All rights reserved World Service Office PO Box 9999 Van Nuys, CA 91409 T 1/818.773.9999 F 1/818.700.0700 www.na.org WSO Catalog Item No. 9146 Living Clean Approval Draft for Decision @ WSC 2012 Table of Contents Preface ......................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One Living Clean .................................................................................................................. 9 NA offers us a path, a process, and a way of life. The work and rewards of recovery are never-ending. We continue to grow and learn no matter where we are on the journey, and more is revealed to us as we go forward. Finding the spark that makes our recovery an ongoing, rewarding, and exciting journey requires active change in our ideas and attitudes. For many of us, this is a shift from desperation to passion. Keys to Freedom ......................................................................................................................... 10 Growing Pains .............................................................................................................................. 12 A Vision of Hope ......................................................................................................................... 15 Desperation to Passion ..............................................................................................................