Sanctuary Theology in the Book of Exodus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuation on the Last Judgment

Continuation on the Last Judgment 1763 © 2009 Swedenborg Foundation This version was compiled from electronic files of the Standard Edition of the Works of Emanuel Swedenborg as further edited by William Ross Woofenden. Pagination of this PDF document does not match that of the corresponding printed volumes, and any page references within this text may not be accurate. However, most if not all of the numerical references herein are not to page numbers but to Swedenborg’s section numbers, which are not affected by changes in pagination. If this work appears both separately and as part of a larger volume file, its pagination follows that of the larger volume in both cases. This version has not been proofed against the original, and occasional errors in conversion may remain. To purchase the full set of the Redesigned Standard Edition of Emanuel Swedenborg’s works, or the available volumes of the latest translation (the New Century Edition of the Works of Emanuel Swedenborg), contact the Swedenborg Foundation at 1-800-355-3222, www.swedenborg.com, or 320 North Church Street, West Chester, Pennsylvania 19380. Contents 1. The last judgment has been accomplished (sections 1–7) 2. The state of the world and of the church before the last judgment and after it (8–13) 3. The last judgment on the reformed (14–31) Continuation on the spiritual world 4. The spiritual world (32–38) 5. The English in the spiritual world (39–47) 6. The Dutch in the spiritual world (48–55) 7. The Papists in the spiritual world (56–60) 8. -

Christ in the Sanctuary READINGS for the WEEK of PRAYER, SEPTEMBER 7-14 �LEO RANZOLIN Official Paper Seventh-Day Adventist Church God Wants to South Pacific Division

September 7, 1996 1 RECORD Christ in the Sanctuary READINGS FOR THE WEEK OF PRAYER, SEPTEMBER 7-14 LEO RANZOLIN Official Paper Seventh-day Adventist Church God Wants to South Pacific Division Editor Bruce Manners Assistant Editors Lee Dunstan. Karen Miller Copy Editor Graeme Brown Dwell With Us Editorial Secretary Lexie Deed Senior Consulting Editor Laurie Evans A Message From the Officers of the Subscriptions South Pacific Division. $A39.00 SNZ48.75. General Conference All other regions, $A77.00 $NZ96.25. Air mail postage rates on application. Order from Signs Publishing Company. Warburton, Victoria 3799, Australia. hen God created Adam and Eve, He placed them in a garden. That was their home. They cared for the flowers, for the ani- Directory of the South Pacific Division 148 Fox Valley Road, Wahroonga, NSW 2076. mals, and for each other. It was indeed Paradise! Our first par- Phone (02) 9847 3333. ents had the presence of God in their home, and happiness was President Bryan Ball their lot. However, as sin stained the world, our parents had to Secretary Laurie Evans Treasurer Warwick Stokes Wbe driven from their first home. Now they needed shelter. They needed a place Assistant to President Alex Currie with a roof over their heads. They needed to build a house or a tent to protect Associate Secretary Vern Parmenter Associate Treasurers Owen Mason, Lynray themselves against the inclement weather. \X ikon As it was in the beginning, God always wants to live with us. To protect us. To Field Secretary Gerhard Pfandl care for us. He wants to dwell with us, and make us happy. -

REUGIOUS TEXTS of the Yezidfs

THE RELIGION OF THE YEZIDIS REUGIOUS TEXTS OF THE YEZIDfS TRANSLATION, INTRODUCTION AND NOTES GIUSEPPE FURLANI TBAKSLATED FROM ITALIAK WITH ADBITIONAL NOTES, AS APPENDIX AND AN INDEX BY JAMSHEDJI MANECKJI UNVALA, Ph.D. (heidelberg). BOaiCM 1910 THE RELIGION OF THE YEZIDIS REUGIOUS TEXTS OF THE YEZIDIS TRANSLATION, INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY GIUSEPPE FURLANI TRANSLATED FROM ITALIAN WITH ADDITIONAL NOTES, AN APPENDIX AND AN INDEX BY JAMSHEDJI MANECKJI UNVALA, Ph.D. (HBlDELBEBa). BOMBAY 19i0 Printed by AHTHOm P. BH BOUBA at the Port Printing Press, No. 28, Qoa Street, Ballard Satate, Bombay 1. PnUisfaedi hy jAMBBSsn MANEOEiii UiiTAtiA, PkD., Mariampura, Maviati CONTENTS PAGE Preface V Introduction ... 1-43 The religion of the Yezidis ... 1 The sect and the cult ... 26 The sacred books ... oM Bibliographical note ... 43 Translation of the texts ... 45-82 The Book of the Eevelation ... 47 The Black Book ... 54 Memorandum of the Yezidis to the Ottoman authorities ... 61 Prayers of the Yezidis ... 68 Catechism of the Yezidis ... 72 The holidays of the Yezidis ... 78 The panegyric {madihdh) of Seyh 'Adi ... 80 Addenda ... 83 Additional notes by the translator ... 84 Appendix by the translator ... 88 Index by the translator ... 94 During my visit to the editing firm of Nicola Zanichelli of Bologna in the summer of 1933, 1 bought a work in Italian entitled " Testi religiosi dei Yezidi " or Eeligious texts of the Yezidis Bologna 1930, written by Prof. Giuseppe Furlani. As I found on its perusal that later Zoroas- trianism had contributed not a little to the formation of the doctrine of the Yezidi religion and that some religious customs and beliefs of the Yezidis had a striking resemblance to those of the Zoroastrians of India and Iran, I decided to place the work before the Parsis in an English translation, following therein the example of my well-wisher and patron, the late Dr. -

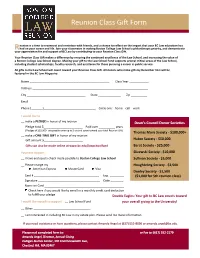

Reunion Class Gift Form

Reunion Class Gift Form eunion is a time to reconnect and reminisce with friends, and a chance to reflect on the impact that your BC Law education has R had on your career and life. Join your classmates in making Boston College Law School a philanthropic priority, and demonstrate your appreciation for and support of BC Law by contributing to your Reunion Class Gift. Your Reunion Class Gift makes a difference by ensuring the continued excellence of the Law School, and increasing the value of a Boston College Law School degree. Making your gift to the Law School Fund supports several critical areas of the Law School, including student scholarships, faculty research, and assistance for those pursuing a career in public service. All gifts to the Law School will count toward your Reunion Class Gift. All donors who make gifts by December 31st will be featured in the BC Law Magazine. Name _________________________________________________ Class Year ____________ Address _______________________________________________________________________ City ____________________________________ State ______________ Zip __________ Email _________________________________________________________________________ Phone (_______)________________________________ Circle one: home cell work I would like to __ make a PLEDGE in honor of my reunion Dean’s Council Donor Societies Pledge total $________________________ Paid over __________ years (Pledges of $10,000+ are payable over up to 5 yrs and count toward your total Reunion Gift) Thomas More Society - $100,000+ __ make a ONE-TIME GIFT in honor of my reunion Huber Society - $50,000 Gift amount $________________________ Gifts can also be made online at www.bc.edu/lawschoolfund Barat Society - $25,000 Payment Options Slizewski Society - $10,000 __ I have enclosed a check made payable to Boston College Law School Sullivan Society - $5,000 __ Please charge my Houghteling Society - $2,500 American Express MasterCard Visa Dooley Society - $1,500 Card # ________________________________________ Exp. -

Balicka-Witakowska Syriac Codicology.Pdf

Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies An Introduction Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies An Introduction Edited by Alessandro Bausi (General Editor) Pier Giorgio Borbone Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet Paola Buzi Jost Gippert Caroline Macé Marilena Maniaci Zisis Melissakis Laura E. Parodi Witold Witakowski Project editor Eugenia Sokolinski COMSt 2015 Copyright © COMSt (Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies) 2015 COMSt Steering Committee 2009–2014: Ewa Balicka-Witakowska (Sweden) Antonia Giannouli (Cyprus) Alessandro Bausi (Germany) Ingvild Gilhus (Norway) Malachi Beit-Arié (Israel) Caroline Macé (Belgium) Pier Giorgio Borbone (Italy) Zisis Melissakis (Greece) Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet (France) Stig Rasmussen (Denmark) =X]DQD*DåiNRYi 6ORYDNLD Jan Just Witkam (The Netherlands) Charles Genequand (Switzerland) Review body: European Science Foundation, Standing Committee for the Humanities Typesetting, layout, copy editing, and indexing: Eugenia Sokolinski Contributors to the volume: Felix Albrecht (FA) Arianna D’Ottone (ADO) Renate Nöller (RN) Per Ambrosiani (PAm) Desmond Durkin-Meisterernst (DDM) Denis Nosnitsin (DN) Tara Andrews (TA) Stephen Emmel (SE) Maria-Teresa Ortega Monasterio (MTO) Patrick Andrist (PAn) Edna Engel (EE) Bernard Outtier (BO) Ewa Balicka-Witakowska (EBW) =X]DQD*DåiNRYi =* Laura E. Parodi (LEP) Alessandro Bausi (ABa) Antonia Giannouli (AGi) Tamara Pataridze (TP) Malachi Beit-Arié (MBA) Jost Gippert (JG) Irmeli Perho (IP) Daniele Bianconi (DB) Alessandro Gori (AGo) Delio Vania Proverbio (DVP) André Binggeli (ABi) Oliver Hahn (OH) Ira Rabin (IR) Pier Giorgio Borbone (PGB) Paul Hepworth (PH) Arietta Revithi (AR) Claire Bosc-Tiessé (CBT) Stéphane Ipert (SI) Valentina Sagaria Rossi (VSR) Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet (FBC) Grigory Kessel (GK) Nikolas Sarris (NS) Paola Buzi (PB) Dickran Kouymjian (DK) Karin Scheper (KS) Valentina Calzolari (VC) Paolo La Spisa (PLS) Andrea Schmidt (AS) Alberto Cantera (AC) Isabelle de Lamberterie (IL) Denis Searby (DSe) Laurent Capron (LCa) Hugo Lundhaug (HL) Lara Sels (LS) Ralph M. -

Sunday, December 6, 2020

Kenilworth Union Church Service of Worship December 6, 2020 Second Sunday of Advent 9:30 a.m. Online CONNECT TO WORSHIP at 9:30 a.m. Prelude Wachet Auf J.S. Bach Joseph Dearest, Joseph Mine Keith Chapman Call to Worship Opening Hymn O Little Town of Bethlehem Lewis Henry Redner 1. O little town of Bethlehem, how still we see thee lie! Above thy deep and dreamless sleep the silent stars go by. Yet in thy dark streets shineth the everlasting light; The hopes and fears of all the years are met in thee tonight. 2. For Christ is born of Mary and, gathered all above, While mortals sleep, the angels keep their watch of wondering love. O morning stars, together proclaim the holy birth, And praises sing to God the king, and peace to all on earth. 3. How silently, how silently, the wondrous gift is given! So God imparts to human hearts the blessings of his heaven. No ear may hear his coming, but in this world of sin, Where meek souls will receive him, still the dear Christ enters in. 4. O holy child of Bethlehem, descend to us, we pray; Cast out our sin and enter in; be born in us today. We hear the Christmas angels the great glad tidings tell; O come to us; abide with us, our Lord Emmanuel! Advent Prayer and Candle Lighting Ministry of Music “Sing Lullaby!” from A Light in the Stable Alan Bullard Sing lullaby! Lullaby baby, now reclining, sing lullaby! Hush, do not wake the infant king. -

LAW and COVENANT ACCORDING to the BIBLICAL WRITERS By

LAW AND COVENANT ACCORDING TO THE BIBLICAL WRITERS by KRISTEN L. COX (Under the Direction of Richard Elliott Friedman) ABSTRACT The following thesis is a source critical analysis of the law and covenant in the Torah of the Hebrew Bible. Specifically I analyze the presentation of the Israelite Covenant in the Sinai Pericope and in Deuteronomy. I present the argument that, while the biblical writers are influenced by the formula of the ancient Near Eastern treaty documents, they each present different views of what happened at Sinai and what content is contained in the law code which was received there. INDEX WORDS: Covenant, Treaty, Law, Israelite law, Old Testament, Hebrew Bible, Torah, Sinai Pericope, Israelite Covenant, Abrahamic Covenant, Davidic Covenant, Noahic Covenant, Suzerain-vassal treaty, Royal grant, ancient Near Eastern law codes LAW AND COVENANT ACCORDING TO THE BIBLCAL WRITERS by KRISTEN L. COX BA , The University of Georgia, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Kristen L. Cox All Rights Reserved LAW AND COVENANT ACCORDING TO THE BIBLICAL WRITERS by KRISTEN L. COX Major Professor: Richard Elliott Friedman Committee: William L. Power Wayne Coppins Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2010 iv DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my all of my family. My mother has been my source of strength every day. My father who passed away my freshman year continues to be my source of inspiration for hard work, integrity and perseverance. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

What Is the Dominant Theme of the Book of Deuteronomy? by Flora Richards-Gustafson, Demand Media

Education Menu ☰ What Is the Dominant Theme of the Book of Deuteronomy? by Flora Richards-Gustafson, Demand Media Deuteronomy is the fifth book of the Torah and of the Bible’s Old Testament. When translated from the Greek Septuagint, the word “Deuteronomy” means “second law,” as in Moses’ retelling of God’s laws. The dominant theological theme in this book is the renewal of God’s covenant and Moses’ call to obedience, as evident in Deuteronomy 4: 1, 6 and 13; 30: 1 to 3 and 8 to 20. Sponsored Link 5,000 Flyers - Only $98 Print 5,000 Flyers for Just $98! Superior Quality & Timely Delivery. overnightprints.com / Flyers People throughout the Bible refer to the Laws of Moses. Summary of Deuteronomy The accounts in Deuteronomy occur in Moab, 40 days before the Related Articles Israelites enter the Promised Land, Canaan. At 120 years old, What Is the Falling Action of "Percy Moses knew that he would soon die, so he took the opportunity to Jackson and the Titan's Curse"? issue a call to obedience and review God’s covenants. Moses recounts the experiences of the past 40 years in the wilderness, What Is the Falling Action of the Book restates the Ten Commandments, and gives the Israelites "Frindle?" guidelines to follow regarding different aspects of life. He tells the Books of the Old Testament in the people that he will die before they enter the Promised Land and English Order appoints Joshua to take his place. Moses gave the Israelites three reasons to renew their obedience to God: God’s history of What Is the Climax of the Book "Rascal?" goodness to his people, the goodness of God’s laws, and God’s unconditional promises of blessings for the future. -

The Centrality to the Exodus of Torah As Ethical Projection

THE CENTRALITY TO THE EXODUS OF TORAH AS ETHICAL PROJECTION Vern Neufeld Redekop Saint Paul University, Ontario How can those liberated from oppression avoid mimesis of their oppressors? When confronted with the stark realities of oppression, the question seems inappropriate, audacious, and even insensitive. Yet history teaches us that it is prudent to confront the question sooner rather than later. That this is a preoccupation of Torah is indicated by the often repeated phrase, "remember that you were slaves in Egypt." In what follows, we will enter the world of the Hebrew Bible to examine the relationship of Torah to the theme of oppression. Our points of entry will be the contemporary gates of liberation theology and Hebrew Bible exegesis. I will argue that Torah as teaching is central to the Exodus, that as teaching it combines awareness of a situation, interpretation of an event, and articulation of practical knowledge. Positively stated, the Exodus paradigm of liberation includes both a freedom from oppression and a freedom to enjoy and develop the resources of the land. This paradigm can be explained, in the vocabulary of Paul Ricoeur, as a transformation of people from sufferers (understood as being acted upon) to actors (being able to take initiative). As such, it addresses the essential question, "How is a liberated people to act?" Torah answers this question through story and stipulation. Its teaching is both indirect and direct. The Exodus concerns not only the flight from Egypt into the promised land, but also the question of how a people is to live in that land. -

Xii Afroasiatica Romana

D S ’A S O XII QUADERNI DI VICINO ORIENTE XII-2017 E T N E I R O O N I C I V I D I N R E D AFROASIATICA ROMANA A U Q A A M G A G 2017 ROMA 2017 QUADERNI DI VICINO ORIENTE SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA _________________________________________________________________________ QUADERNI DI VICINO ORIENTE XII - 2017 AFROASIATICA ROMANA “PROCEEDINGS OF THE 15TH MEETING OF AFROASIATIC LINGUISTICS” 17-19 September 2014, Rome edited by Alessio Agostini and Maria Giulia Amadasi Guzzo ROMA 2017 QUADERNI DI VICINO ORIENTE SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA _________________________________________________________________________ Direttore Scientifico: Lorenzo Nigro Redazione: Daria Montanari, Federico Cappella ISSN 1127-6037 e-ISSN 2532-5175 Frontcover: Maxim Kantor, Babel Tower (2008). Courtesy of the Artist. QUADERNI DI VICINO ORIENTE SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA _________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Introdu i M.I. Ababneh - Kinship terms in Safaitic inscriptions 1 S. Anthonioz - -: toward a philological and exegetical hypothesis 29 F. Aspesi - Ebraico biblico e il sostrato linguistico egeo-cananaico 39 L. Avallone - Neither fu nor : how to reach a simplified Arabic - and practice of the Third Language 47 S. Baldi - R. Leger - Gender in Hausa and Igbo proverbs 55 G. Banti - M. Vergari- Aspects of Saho dialectology 65 A. Boucherit - Spatial deixis and interlocution space in Algerian Arabic tales 83 D. Calabro - Inalienable possession in early Egypto-Semitic genitive constructions 91 M. Campanelli - Conflict in government (T): the treatment of the coordination reduction inside the Arabic linguistic tradition 107 G. Castagna - Towards a systematisation of the broken plural patterns in the Mehri language of Oman and Yemen 115 A.