For Reference Use Only

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filing Port Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Last

Filing Last Port Call Sign Foreign Trade Official Voyage Vessel Type Dock Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Last Domestic Port Vessel Name Last Foreign Port Number IMO Number Country Code Number Number Vessel Flag Code Agent Name PAX Total Crew Operator Name Draft Tonnage Owner Name Dock Name InTrans 5301 HOUSTON, TX 5301-2021-01647 1/1/2021 - GOLDENGATE PARK RIO JAINA D5EL2 9493145 DO 1 16098 64 LR 150 NORTON LILLY INTL 0 23 MADDSIN SHIPPING LTD. 18'0" 6115 MADDSIN SHIPPING LTD. ITC DEER PARK DOCK NO 7 L 2002 NEW ORLEANS, LA 2002-2021-00907 1/1/2021 HOUSTON, TX AS Cleopatra - V2DV3 9311787 - 6 4550 051N AG 310 NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL 3 17 AS CLEOPATRA SCHIFFAHRTSGESELLSCHAFT MBH & CO., KG 37'9" 13574 AS CLEOPATRA SCHIFFAHRTSGESELLSCHAFT MBH & CO., KG NASHVILLE AVENUE WHARVES A, B AND C DFLX 4106 ERIE, PA 4106-2021-00002 1/1/2021 - ALGOMA BUFFALO HAMILTON, ONT WXS6134 7620653 CA 1 841536 058 CA 600 WORLD SHIPPING INC. 0 20 ALGOMA CENTRAL CORPORATION CANADA 22'6" 5107 ALGOMA CENTRAL CORPORATION CANADA DONJON SHIPBUILDING & REPAIR N 2002 NEW ORLEANS, LA 2002-2021-00906 1/1/2021 HOUSTON, TX TEMPANOS - A8VP9 9447897 - 6 92780 2044N LR 310 NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL 2 26 HAPAG-LLOYD/ GERMANY 39'4" 42897 HULL 1794 CO. LTD NASHVILLE AVENUE WHARVES A, B AND C DFLX 1103 WILMINGTON, DE 1103-2021-00185 1/1/2021 PORTSMOUTH, NH HOURAI MARU - V7A2157 9796585 - 4 8262 1 MH 210 MORAN SHIPPING AGENCIES, INC 0 24 SYNERGY MARITIME PRIVATE LIMITED 23'4" 7638 SOUTHERN PACIFIC HOLDING CORPORATION SUNOCO MARCUS HOOK L 2904 PORTLAND, OR 2904-2021-00150 1/1/2021 - PAN TOPAZ KUSHIRO 3FMZ5 9625827 JP 1 43732-12-B 52 PA 229 transmarine navigation corp. -

In Pueblo's Wake

IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO by JAMES A. DUERMEYER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN U.S. HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2016 Copyright © by James Duermeyer 2016 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to my professor and friend, Dr. Joyce Goldberg, who has guided me in my search for the detailed and obscure facts that make a thesis more interesting to read and scholarly in content. Her advice has helped me to dig just a bit deeper than my original ideas and produce a more professional paper. Thank you, Dr. Goldberg. I also wish to thank my wife, Janet, for her patience, her editing, and sage advice. She has always been extremely supportive in my quest for the masters degree and was my source of encouragement through three years of study. Thank you, Janet. October 21, 2016 ii Abstract IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO James Duermeyer, MA, U.S. History The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Joyce Goldberg On January 23, 1968, North Korea attacked and seized an American Navy spy ship, the USS Pueblo. In the process, one American sailor was mortally wounded and another ten crew members were injured, including the ship’s commanding officer. The crew was held for eleven months in a North Korea prison. -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

Fixed Link Between Labrador and Newfoundland Pre-Feasibility Study Final Report

Fixed Link between Labrador and Newfoundland Pre-feasibility Study Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................. 1 Background and Purpose ............................................ 1 Overview of Previous Work ......................................... 1 Other Relevant Fixed Links & Tunnels Worldwide .................... 1 The Environment and Geology of the Study Area ..................... 1 Assessment of Alternative Fixed Link Concepts ..................... 2 Bridge..............................................................2 Causeway............................................................2 Tunnels.............................................................2 Comparison Summary of Alternatives..................................3 Implementation Schedule ........................................... 4 Regulatory and Environmental Issues ............................... 4 Economic and Business Case Analysis ............................... 4 Financing Considerations .......................................... 7 Conclusions ....................................................... 7 1 INTRODUCTION................................................... 8 1.1 Background and Purpose....................................... 8 1.2 Overview of Previous Work.................................... 9 1.3 Study Approach.............................................. 10 2 REVIEW OF RELEVANT FIXED LINKS WORLDWIDE...................... 12 2.1 Øresund Link............................................... -

Legislating for Brexit: EU Decisions

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8205, 18 January 2018 Legislating for Brexit: EU By Vaughne Miller Decisions Contents: 1. EU law in force 2. What are EU decisions? 3. Brexit legislation 4. Other Brexit-related Bills 5. Annex I – JHA framework decisions 6. Annex II - CFSP common positions, joint actions and decisions 7. Annex III - Council and Council/EP decisions 8. Annex IV - Commission decisions www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Legislating for Brexit: EU Decisions Contents Summary 4 1. EU law in force 8 2. What are EU decisions? 10 2.1 Binding measures 10 Article 288 TFEU 10 Legislative and non-legislative decisions 10 Delegated and implementing decisions 11 2.2 Commission decisions 11 Directly applicable 12 Direct effect 13 2.3 Council decisions 13 TFEU decisions 13 TEU decisions 13 2.4 Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) decisions and framework decisions 14 Framework decisions 14 UK JHA opt-out and opt-in arrangements 15 2.5 Common Foreign and Security Policy decisions 17 A different kind of EU decision 17 Decisions about international relations 18 Some sanctions decisions need an accompanying regulation 18 Council decisions on external agreements 20 3. Brexit legislation 23 3.1 The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill 23 Retained EU law 23 3.2 The EUW Bill and EU decisions 23 Clause 8 26 4. Other Brexit-related Bills 27 4.1 Bills to allow government amendment of policies after Brexit 27 The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Bill 27 The Trade Bill 29 The Taxation (Cross-border Trade) Bill 29 The Nuclear Safeguards Bill 30 5. -

TP 14876E Study on Potential Hub-And-Spoke Container Transhipment Operations in Eastern Canada for Marine Movements of Freight (

TP 14876E Study on Potential Hub-and-Spoke Container Transhipment Operations in Eastern Canada for Marine Movements of Freight (Short Sea Shipping) Final Discussion Report Prepared for: Transport Canada by: CPCS Transcom Limited December 2008 TP 14876E Study on Potential Hub-and-Spoke Container Transhipment Operations in Eastern Canada for Marine Movements of Freight (Short Sea Shipping) Final Discussion Report Prepared by: James Frost and Marc-André Roy CPCS Transcom Limited with Mary R. Brooks and Mike Zelman December 2008 EASTERN CANADA HUB-AND-SPOKE (SHORT SEA SHIPPING) STUDY FINAL DISCUSSION REPORT Notices This report reflects the views of the authors and not necessarily the official views or policies of Transport Canada. Transport Canada does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are essential to its objectives. Since some of the accepted measures in the industry are imperial, metric measures are not always used in this report. Un sommaire français se trouve avant la table des matières. © Her Majesty the Queen in right on Canada 2008 as represented by the Minister of Transport ii Transport Transports Canada Canada PUBLICATION DATA FORM 1. Transport Canada Publication No. 2. Project No. 3. Recipient’s Catalogue No. TP 14876E --- 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Publication Date Study on Potential Hub and Spoke Container Transshipment December 2008 Operations in Eastern Canada for Marine Movements of Freight (Short Sea Shipping) 6. Performing Organization Document No. 08078 7. Author(s) 8. Transport Canada File No. James Frost, Marc-André Roy, Mary R. Brooks, and Mike Zelman --- 9. -

Fourteenth Report: Draft Statute Law Repeals Bill

The Law Commission and The Scottish Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 211) (SCOT. LAW COM. No. 140) STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT DRAFT STATUTE LAW (REPEALS) BILL Presented to Parliament by the Lord High Chancellor and the Lord Advocate by Command of Her Majesty April 1993 LONDON: HMSO E17.85 net Cm 2176 The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the Law. The Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Mr. Justice Brooke, Chairman Mr Trevor M. Aldridge, Q.C. Mr Jack Beatson Mr Richard Buxton, Q.C. Professor Brenda Hoggett, Q.C. The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Collon. Its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. The Scottish Law Commissioners are- The Honourable Lord Davidson, Chairman .. Dr E.M. Clive Professor P.N. Love, C.B.E. Sheriff I.D.Macphail, Q.C. Mr W.A. Nimmo Smith, Q.C. The Secretary of the Scottish Law Commission is Mr K.F. Barclay. Its offices are at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh EH9 1PR. .. 11 THE LAW COMMISSION AND THE SCOTTISH LAW COMMISSION STATUTE LAW REVISION: FOURTEENTH REPORT Draft Statute Law (Repeals) Bill To the Right Honourable the Lord Mackay of Clashfern, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and the Right Honourable the Lord Rodger of Earlsferry, Q.C., Her Majesty's Advocate. In pursuance of section 3(l)(d) of the Law Commissions Act 1965, we have prepared the draft Bill which is Appendix 1 and recommend that effect be given to the proposals contained in it. -

ZEEBRIEF#153 13 April 2019

ZEEBRIEF#153 13 april 2019 Mutaties Nederlandse zeeschepen, Nieuwsbrief-255 AALSMEERGRACHT (NB-254), AALSMEERGRACHT heet toch echt wel officieel vertaalt GRIGORY SHELIKHOV en geen Grigoriy ….. Maar what’s in a name! Zij lezen de laatste twee letters als een i en een y, maar officieel is dat een i en een j (klinkt als iej), die combinatie wordt dan weer internationaal geschreven als een y. Kortom de laatste twee Russische letters samen staan voor een enkele y. Afhankelijk van het Russische dialect en het jaartal waarin de vertaling is gemaakt worden de i en y afzonderlijk ook nog verschillend gebruikt. Zo ken ik nog wel een paar voorbeelden Tiksi of Tiksy, Taymir en Tambey. (Bron: medewerker Spliethoff. Foto: Kees Bustraan†). ALGERIAN EXPRESS, IMO 9108221 (NB-133), 10-1995 opgeleverd door China Shipbuilding Corp., Kaohsiung (597) als KUO FAH aan Cheng Lie Navigation Co. Ltd., Taipei. 15.095 GT, 6.453 NT. 18.294 DWT. 1295 TEU. 17 kn. 11.050 EPK, 8.128 kW, B&W, Hitachi Zosen Corp. 1995 verkocht aan Cho Yang Shipping Co. Ltd., Panama, 1995 herdoopt CHOYANG LEADER. 2001 verkocht aan Heung-A Shipping Co. Ltd., Busan, vlag: Panama, 18-6-2001 herdoopt YOUNG LIBERTY. 12-2002 verkocht aan Algerian Express Corp., Panama, in beheer bij Vroon B.V. 4-2004 verkocht aan Allocean Charters Ltd., Hong Kong, roepsein VRAA3, in beheer bij Teekay Marine Services AS, voor 2 jaar in timecharter bij Vroon B.V. 23-5-2005 (e) verkocht aan Allocean Maritime Container No. 1, Hong Kong, in beheer bij Univan Ship Management Ltd., 30-8-2005 (e) herdoopt ALGERIAN EXPRESS. -

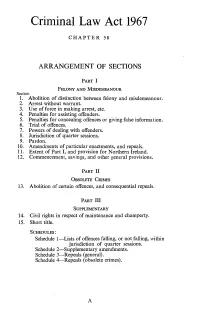

Arrangement of Sections

Criminal Law Act 1967 CHAPTER 58 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Section 1. Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. 2. Arrest without warrant. 3. Use of force in making arrest, etc. 4. Penalties for assisting offenders. 5. Penalties for concealing offences or giving false information. 6. Trial of offences. 7. Powers of dealing with offenders. 8. Jurisdiction of quarter sessions. 9. Pardon. 10. Amendments of particular enactments, and repeals. 11. Extent of Part I, and provision for Northern Ireland. 12. Commencement, savings, and other general provisions. PART 11 OBSOLETE CRIMES 13. Abolition of certain offences, and consequential repeals. PART III SUPPLEMENTARY 14. Civil rights in respect of maintenance and champerty. 15. Short title. SCHEDULES: Schedule 1-Lists of offences falling, or not falling, within jurisdiction of quarter sessions. Schedule 2-Supplementary amendments. Schedule 3-Repeals (general). Schedule 4--Repeals (obsolete crimes). A Criminal Law Act 1967 CH. 58 1 ELIZABETH n , 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] E IT ENACTED by the Queen's most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and BTemporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR 1.-(1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are J\b<?liti?n of hereby abolished. -

Record of Vessel in Foreign Trade Entrances

Filing Last Port Call Sign Foreign Trade Official Voyage Vessel Type Dock Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Last Domestic Port Vessel Name Last Foreign Port Number IMO Number Country Code Number Number Vessel Flag Code Agent Name PAX Total Crew Operator Name Draft Tonnage Owner Name Dock Name InTrans 3801 DETROIT, MI 3801-2021-00374 8/13/2021 - ALGOMA NIAGARA PORT COLBORNE, ONT CFFO 9619270 CA 2 840674 30 CA 330 WORLD SHIPPING INC 0 19 ALGOMA CENTRAL CORP. 23'0" 8979 ALGOMA CENTRAL CORP. ST. MARYS CEMENT CO., DETROIT PLANT WHARF D 5301 HOUSTON, TX 5301-2021-05471 8/13/2021 - IONIC STORM PUERTO QUETZAL V7BQ9 9332963 GT 1 5190 71 MH 229 Southport Agencies 0 20 IONIC SHIPPING (MGT) INC 32'0" 18504 SCOTIA PROJECTS LTD CITY DOCK NOS. 41 - 46 L 3002 TACOMA, WA 3002-2021-00775 8/13/2021 - HYUNDAI BRAVE VANCOUVER, BC V7EY4. 9346304 CA 3 7477 95 MH 310 HYUNDAI AMERICA SHIPPING AGENCY 0 25 HMM OCEAN SERVICE CO. LTD 38'5" 51638 SHIP OWNER INVESTMENT CO NO 7 S.A. WASHINGTON UNITED TERMINALS, TACOMA WHARF (WUT) DFL 5301 HOUSTON, TX 5301-2021-05472 8/13/2021 - NAVIGATOR EUROPA DAESAN D5FZ3 9661807 KR 2 16397 2102 LR 150 Fillette Green Shipping 0 20 NAVIGATOR EUROPA LLC 36'5" 5163 NAVIGATO EUROPA LLC BAYPORT RO RO TERMINAL D 1816 PORT CANAVERAL, FL 1816-2021-00412 8/13/2021 - DISNEY DREAM CASTAWAY CAY C6YR6 9434254 BS 1 8001800 1081 BS 350 Disney Cruise Lines 1348 1230 MAGICAL CRUISE COMPANY LIMITED 28'2" 104345 MAGICAL CRUISE COMPANY LIMITED CT8 DISNEY CRUISE TERMINAL 8 N 3001 SEATTLE, WA 3001-2021-01615 8/13/2021 SKAGWAY, AK CELEBRITY MILLENNIUM - 9HJF9 9189419 - 4 9189419 56800 MT 350 INTERCRUISES SHORESIDE & PORT SERVICES 1142 744 CELEBRITY CRUISES INC. -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

Watriama and Co Further Pacific Islands Portraits

Watriama and Co Further Pacific Islands Portraits Hugh Laracy Watriama and Co Further Pacific Islands Portraits Hugh Laracy Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Laracy, Hugh, author. Title: Watriama and Co : further Pacific Islands portraits / Hugh Laracy. ISBN: 9781921666322 (paperback) 9781921666339 (ebook) Subjects: Watriama, William Jacob, 1880?-1925. Islands of the Pacific--History. Dewey Number: 995.7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Preface . ix 1 . Pierre Chanel of Futuna (1803–1841): The making of a saint . 1 2 . The Sinclairs Of Pigeon Bay, or ‘The Prehistory of the Robinsons of Ni’ihau’: An essay in historiography, or ‘tales their mother told them’ . 33 3 . Insular Eminence: Cardinal Moran (1830–1911) and the Pacific islands . 53 4 . Constance Frederica Gordon-Cumming (1837–1924): Traveller, author, painter . 69 5 . Niels Peter Sorensen (1848–1935): The story of a criminal adventurer . 93 6 . John Strasburg (1856–1924): A plain sailor . 111 7 . Ernest Frederick Hughes Allen (1867–1924): South Seas trader . 127 8 . Beatrice Grimshaw (1870–1953): Pride and prejudice in Papua . 141 9 . W .J . Watriama (c . 1880–1925): Pretender and patriot, (or ‘a blackman’s defence of White Australia’) .