A Navy Doctor at War I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Pueblo's Wake

IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO by JAMES A. DUERMEYER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN U.S. HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2016 Copyright © by James Duermeyer 2016 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to my professor and friend, Dr. Joyce Goldberg, who has guided me in my search for the detailed and obscure facts that make a thesis more interesting to read and scholarly in content. Her advice has helped me to dig just a bit deeper than my original ideas and produce a more professional paper. Thank you, Dr. Goldberg. I also wish to thank my wife, Janet, for her patience, her editing, and sage advice. She has always been extremely supportive in my quest for the masters degree and was my source of encouragement through three years of study. Thank you, Janet. October 21, 2016 ii Abstract IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO James Duermeyer, MA, U.S. History The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Joyce Goldberg On January 23, 1968, North Korea attacked and seized an American Navy spy ship, the USS Pueblo. In the process, one American sailor was mortally wounded and another ten crew members were injured, including the ship’s commanding officer. The crew was held for eleven months in a North Korea prison. -

For Reference Use Only

b559M Ui,,,i,%'ERSjTY OFGRLENYSa ' LýERARY FORREFERENCE USEONLY UNIVERSITY OF GREENWICH GREENWICH MARITIME INSTITUTE THE SEAFARER, PIRACY AND THE LAW A HUMAN RIGHTS APPROACH P. G. Widd BSc, MA Master Mariner A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Greenwich May 2008 Vol V\j UINIv tiTY OFGREENWICH LIBRARY FORRFFFRFPICF ! 1SF ÖNl Y ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With thanks to the following: ProfessorA. D. Couper for much helpful "pilotage" advice, keeping this thesis on course. P. Mukundan of the International Maritime Bureau for answering my questions with good humour and supplying me with the piracy reports. Brigadier(Retd) B. A. H. Parritt CBE for allowing me to share in small measure his expertise on security. III ABSTRACT been Piracy at seahas existed almost since voyaging began and has effectively Navy in 1stC subduedfrom time to time, principally by the Roman Imperial the and the British Navy in the 19thC. Over the past twenty five years piracy has once again been increasing such that it has now become of serious concern to the maritime bears brunt community, in particular the seafarer,who as always the of these attacks. developed from In parallel with piracy itself the laws of piracy have the Rhodian Laws through Roman Law, post Treaty of Westphalia Law both British and Convention American until today the Law of Piracy is embodied in the United Nations be of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982. Under this Law piracy can only committed on the high seasand with UNCLOS increasing the limit of the territorial seafrom 3m1.to 12ml. -

1944, Service Record

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons George V. Tudor Second World War Series 4. Service Document Photocopies Correspondence Collection 7-21-1944 1944, Service Record Unknown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/ gvtudor_correspondence_service_documents Part of the Cultural History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Military History Commons, Other History Commons, Political History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Unknown, "1944, Service Record" (1944). Series 4. Service Document Photocopies. 4. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/gvtudor_correspondence_service_documents/4 This Service Document is brought to you for free and open access by the George V. Tudor Second World War Correspondence Collection at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Series 4. Service Document Photocopies by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1944, Service Record Keywords Service Record Disciplines Cultural History | History of Science, Technology, and Medicine | Military History | Other History | Political History | Public History | Social History | United States History Identifier 2015-083-w-r-_Tudor_WWII_Expeditions This service document is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/ gvtudor_correspondence_service_documents/4 EXPEDITIONS, ENGAGEMENTS, DISTINGUISHED SERVICE NAME ETx,1R,) GEOl<.G-E V SERVICE NUMBER Sb-3 55/ Embarked on board U.S.S. Heywood at San Diego,· Calif.,June 17, 19 Onbo'ard USS HEYWO.OD J. 42 and sailed June 18, 194~. Jr?s~~d the E~uator 26Jun42; ~rrived at APIA, SAMOA on .,_nitiated as 1 Shell - backlf 1Jul42 Disembarked on on 27Jun42. -

Watriama and Co Further Pacific Islands Portraits

Watriama and Co Further Pacific Islands Portraits Hugh Laracy Watriama and Co Further Pacific Islands Portraits Hugh Laracy Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Laracy, Hugh, author. Title: Watriama and Co : further Pacific Islands portraits / Hugh Laracy. ISBN: 9781921666322 (paperback) 9781921666339 (ebook) Subjects: Watriama, William Jacob, 1880?-1925. Islands of the Pacific--History. Dewey Number: 995.7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Preface . ix 1 . Pierre Chanel of Futuna (1803–1841): The making of a saint . 1 2 . The Sinclairs Of Pigeon Bay, or ‘The Prehistory of the Robinsons of Ni’ihau’: An essay in historiography, or ‘tales their mother told them’ . 33 3 . Insular Eminence: Cardinal Moran (1830–1911) and the Pacific islands . 53 4 . Constance Frederica Gordon-Cumming (1837–1924): Traveller, author, painter . 69 5 . Niels Peter Sorensen (1848–1935): The story of a criminal adventurer . 93 6 . John Strasburg (1856–1924): A plain sailor . 111 7 . Ernest Frederick Hughes Allen (1867–1924): South Seas trader . 127 8 . Beatrice Grimshaw (1870–1953): Pride and prejudice in Papua . 141 9 . W .J . Watriama (c . 1880–1925): Pretender and patriot, (or ‘a blackman’s defence of White Australia’) . -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

![The American Legion [Volume 142, No. 3 (March 1997)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6999/the-american-legion-volume-142-no-3-march-1997-3606999.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 142, No. 3 (March 1997)]

Le Sabre Peac IBl 1 TO LeSabre Peace of mind. $500 Member Benefit January 15 through March 31, 1997 LeSabre, LeSabre Living Space Safe Priorities Comfort and quality are synonymous with LeSabre. From the carefully contoured seats to the refined quiet ride, Buick continues to build a strong safety reputation with a wide the confidence that Buick array of standard safety features such as dual airbags and anti- owners experience is the lock brakes. The safety and security of you and your family are most important quality top priorities with LeSabre. There has never been a better of all time to visit your local Buick dealer Take advantage of Buick savings as a member of the So drive into your local American Legion family From Buick dealer today with the January 15 through March 31, attached American Legion 1997, you can save $500 in $500 Member Benefit addition to a LeSabre national Certificate from LeSabre. cash-off incentive on the When you purchase or lease purchase or lease of a new your 1997 LeSabre, you'll also and unused 1997 LeSabre. be contributing to a very The optional leather interior features a wrap around See your local Buick dealer worthy cause. Buick will instrument panel. for details. donate $100 to your local Post or Auxiliary for the support of American Legion Baseball. LeSabre offers dual air bags as a standard feature. Always wear When filling out your member certificate, remember to include your safety belts even with your local Post # or Auxiliary Unit #. LeSabre, The American Another powerful reason for LeSabre 's best seller status, the 3800 Series II V6 engine's 205 horsepower Legion's Choice A full-size car with its powerful 3800 Series 11 SFI V6 engine provides effortless cruising for a family of six. -

October 2004

October November December 2004 "Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if again sounded, to provide firepower for freedom…” THE JERSEYMAN The Battle of Leyte Gulf... Sixty years ago, naval forces of the United States and Australia dealt a deadly and final blow to the Japanese Navy at Leyte Gulf. Over a four day period ranging from 23 - 26 October 1944, and in four separate engagements, the Japanese Navy lost 26 ships and the US Navy lost 6. With this issue of The Jerseyman, we present another look back at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, record some new stories, and present a few 60 year old, but “new” photos sent in by the men that were there. Our sincere thanks to all WW2 veterans, and Battle of Leyte Gulf veterans for their contributions to this issue. History also records that the Battle of Leyte Gulf was the one time in the Pacific war that Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, flying his flag aboard battleship USS NEW JERSEY, had a chance to take on the giant Japanese battleships IJN Musashi, and IJN Yamato. But in a controversial decision that is studied and discussed to this day, Admiral Halsey took the bait of a Japanese carrier decoy fleet, split his forces, and headed USS NEW JERSEY and the Third Fleet North. Admiral Halsey lost his chance. The greatest sea-battle victory in history fell instead to the older ships of the United States Seventh Fleet. We can only speculate on what it would have meant if Halsey’s Third Fleet had been there with the old Seventh Fleet battleships of WEST VIRGINIA, CALIFORNIA, TENNESSEE, MARYLAND, PENNSYLVANIA, and- MISSISSIPPI, and had added the firepower from fast battleships NEW JERSEY, IOWA, MASSACHUSETTS, SOUTH DAKOTA, WASHINGTON and ALABAMA… The flag shown is on display in the museum area of the ship. -

Forgotten Battles of Attu & Kiska

JUNE 2020 FORGOTTEN BATTLES OF ATTU & KISKA INSIDE: 9 On & Off the Hill 26 Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum 37 Education Foundation $175,000 IN GOLD COULD BE WORTH OVER ONE MILLION DOLLARS id you know that if you would have taken $175,000 of your money and bought Dphysical gold in 2000, you would now have over $1 million at today’s gold prices?* That’s an incredible increase of over 525%, outperforming the Nasdaq, Dow, and S&P 500. Many analysts believe that the long-term gold bull run has only just begun and predict its current price to rise—even DOUBLE—in the future. That’s why we believe now is the time to diversify your money with physical gold before prices move to new highs. growth 525% “Don’t play games with your money.” —Chuck Woolery USMR customer & paid spokesperson Unlock the secret to wealth protection with YOUR FREE GOLD INFORMATION KIT U.S. Money Reserve proudly announces As the only gold company led by our release of the ultimate 2020 Gold a former U.S. Mint Director, we Information Kit—and it’s yours know trust is our most valuable absolutely FREE. Plus! Call right now asset. With over 525,000 clients to also receive two exclusive BONUS served, we have a track record reports: 25 Reasons to Own Gold AND of trustworthy and ethical the 2020 Global Gold Forecast. That’s business practices, including over 85 pages of insider information an A+ RATING from the you won’t fi nd anywhere else with no Better Business Bureau and CALL NOW purchase required. -

![The American Legion [Volume 124, No. 2 (February 1988)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0430/the-american-legion-volume-124-no-2-february-1988-4110430.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 124, No. 2 (February 1988)]

• THE AMERICAN 1 Legion FOR GOD AND COUNTRY February 1988 TWO DOLLARS HOW VALID ARE THE POLLS? THE SILENT KILLER American Industry ROBOTS FOR DEFENSE CAN WE MOBILIZE FOR WAR? OUR ENDANGERED INDUSTRIAL BASE k - - ..xV • - • - —»— i * 5 -j .;•/'-• if] ^iff] Lj-i-l-'f t-i-> L/j.U * • » « '**."*. * •*•» «•" r? . !m .T ^ ; / > jjflj *yj ^ .l^" /c3J . TLmerican Oailored Executive Slacks pairs for only Without Question, the Best Buy in men's clothing in America today, from Haband the mail order people from Paterson, New Jersey. These are beautifully tailored executive fashion slacks suitable for both business and social occasions. You get comfortable executive cut, cool crisp no-wrinkle performance, 100% no-iron machine wash and wear, and countless detailing niceties. Straight flat front, easy diagonal front pockets, two safeguard back pockets, deep "no-hole" pocketing, Talon® unbreakable "Zephyr" zipper, Ban-Rol® no-roll inner waistband, Hook Flex® hook and eye closure, and full finish tailoring throughout. Fabric is 100% Fortrel® Polyester S-T-R-E-T-C-H, for easy give-and-take as you sit, stride, bend or move. And now for the Spring and Summer vacation season, 8 new colors to choose! We have your exact size in stock! Waists 30-32-34-35-36- 37-38-39-40-41-42-43-44. *Big Men's Department, please add $2.00 per pair for 46-48-50-52-54. Leg Length: 27-28-29- 30-31-32-33-34, already to wear! SIMPLY TELL US YOUR SIZE!!! No shopping around or costly alterations. We ship direct to your door — Fill out the coupon for EASY At-Home A Try-On Approval! "American Gailoreti Executive Slacks LT. -

Mobility, Support, Endurance : a Story of Naval Operational Logistics in The

BMmi : "^ ; ;tl!!tl! sll> 1 i ^^^^^^^^^^H if m nil i iii 11 i im m MONGOLIA ; X)SUKA CHI CHI JIMA N AWA ^ti^?=^"a:PCKNER BAY 'AN ISIUNG 'ING HARBOR ^i^JtlAM \0! PPINE: EQUATO-B- Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/mobilitysupporteOOhoop QXfOP,0(^ MOBILITY, SUPPORT ENDURANCE A Story of Naval Operational Logistics in the Vietnam War 1965-1968 by VICE ADMIRAL EDWIN BICKFORD HOOPER, USN (Retired) NAVAL HISTORY DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY WASHINGTON, D.C., 1972 LC Card 76-184047 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1972 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402—Price S4.25 Stock Number 0846-0057 Dedication Dedicated to the logisticians of all Services and in all wars, and in particular, to the dedicated, and often heroic, ofl&cers and men of the Service Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet. UNNTED STATES NH-74351 The globe as viewed from over the intersection of the Date Line and Equator. Foreword In narrating the naval history of a war, one approach open to a historian is to record the general story of naval operations, then complement the main history with works dealing with specialized fields. The Naval History Division plans to follow this approach in the case of the Vietnam War, focusing the Division's efforts primarily on an account of naval operations but accompanying the major history with publications in limited fields deserving of treatment beyond that to be given in the main work. -

Salute to Veterans

9 Choose Your Ohio Location Special Edition MISSION IN Mount Pleasant Retirement Village* MISSION IN Monroe (513) 539-7391 In this Special Issue Park Vista Retirement A Tribute to Our Troops ................ 3 Community* Youngstown Honor Flight Founder (330) 746-2944 Visits Dorothy Love .......................24 OPRS Reaches Out to Rockynol* Veterans and Troops .....................25 Akron A Salute The Lima Company Memorial ... 26 (330) 867-2150 Sue Mooney Wins National to OPRS Award ............................................ 28 Dorothy Love FOCUS on Employees .................29 Retirement Swan Creek Community* Retirement Village* Veter ans: Sidney Toledo Breckenridge Village* (937) 498-2391 (419) 865-4445 Willoughby (440) 942-4342 Lake Vista The Vineyard of Cortland on Catawba Cortland Port Clinton Cape May (330) 638-2420 (419) 797-3100 Retirement Village Wilmington Honoin ose (937) 382-2995 Llanfair Retirement Westminster-Thurber Community* Community* Cincinnati Columbus *Accredited by the Commission on (513) 681-4230 (614) 228-8888 o Srved Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) – Continuing Care Accreditation Commission (CCAC) of the American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging (AAHSA). Wth Hono NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATION For more information U.S. POSTAGE Our mission Ohio Presbyterian PAID COLUMBUS, OH is to provide Retirement Services and PERMIT NO. 227 older adults the OPRS Foundation 1001 Kingsmill Parkway with caring and quality services 1001 Kingsmill Parkway Columbus, Ohio 43229 www.oprs.org toward the enhancement of Columbus, Ohio 43229 physical, (614) 888-7800 or (800) 686-7800. mental Senior Independence and spiritual Home and Community Based well-being Services in 38 Ohio counties, consistent with (800) 686-7800. the Christian Gospel. Volume 10 • Issue 2 • 2008 Dear Friends, When you think of those who have served in the military, no matter what branch or which war, certain words come to mind. -

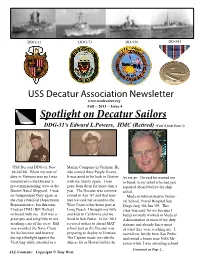

Spotlight on Decatur Sailors DDG-31’S Edward L.Powers, HMC (Retired) (Cont’D from Issue 3)

DDG-31 DDG-73 DD-936 DD-341 USS Decatur Association Newsletter www.ussdecatur.org Fall -- 2013 -- Issue 4 Spotlight on Decatur Sailors DDG-31’s Edward L.Powers, HMC (Retired) (Cont’d from Issue 3) USS Decatur DDG-31 Nov Marine Company in Vietnam. He ‘66-Jul’68. When my tour of also earned three Purple Hearts. duty in Vietnam was up I was It was good to be back in Boston let me go. He said he wanted me transferred to the Decatur’s with my family again. I was to break in my relief who had just pre-commissioning crew at the gone from them for more than a reported aboard before the ship Boston Naval Shipyard. I was year. The Decatur was commis- sailed. on Independent Duty again as sioned in Apr ‘67 and that sum- Medical Administrative Techni- the ship’s Medical Department mer we took her around to the cal School, Naval Hospital San Representative, but this time West Coast to her home port at Diego Aug ‘68-Jun ‘69. This I had an HM2 (Bill Hickey) Long Beach. I brought my wife class was easy for me because I on board with me. Bill was a and kids to California and we had previously worked in Medical great guy and a big help to me lived in San Pedro. In Jul ‘68 I Administation at most of my duty in taking care of the crew. Bill received orders to attend MAT stations and already knew most was awarded the Navy Cross school just as the Decatur was of what they were teaching me.