Cyavana Helps Ashvins, Prometheus Helps Humans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17-Chapter-16-Versewise.Pdf

BHAGAVAD GITA Chapter 16 Daivasura-Sampad-Vibhaga Yoga (The Divine and Demoniac Natures Defined) 1 Chapter 16 Introduction : 1) Of vain hopes, of vain actions, of vain knowledge and senseless (devoid of discrimination), they verily are possessed of the delusive nature of raksasas and asuras. [Chapter 9 – Verse 12] Asura / Raksasa Sampad : • Moghasah, Mogha Karmanah – false hopes from improper actions. Vicetasah : • Lack of discrimination. • Binds you to samsara. 2) But the Mahatmas (great souls), O Partha, partaking of My divine nature, worship Me with a single mind (with a mind devoted to nothing else), knowing Me as the imperishable source of all beings. [Chapter 9 – Verse 13] Daivi Sampad : • Seek Bagawan. • Helps to gain freedom from Samsara. 2 • What values of the mind constitute spiritual disposition and demonic disposition? Asura – Sampad Daivi Sampad - Finds enjoyment only in - Make choice as per value sense objects. structure, not as per - Will compromise to gain convenience. the end. • Fields of experiences - Kshetram change but the subject Kshetrajna, knower is one in all fields. • Field is under influence of different temperaments – gunas and hence experiences vary from individual to individual. • Infinite is nature of the subject, transcendental state of perfection and pure knowledge (Purushottama). • This chapter describes how the knower pulsates through disciplined or undisciplined field of experience. • Field is the 3 gunas operative in the minds of individuals. • Veda is a pramana only for prepared mind. Values are necessary to gain knowledge – chapter 13, 14, 15 are direct means to liberation through Jnana yoga. Chapter 16, 17 are values to gain knowledge. 3 Chapter 16 - Summary Verse 1 - 3 Verse 4 - 21 Verse 22 Daivi Sampat (Spiritual) – 18 Values Asuri Sampat (Materialistic) – 18 Values - Avoid 3 traits and adopt daivi sampat and get qualifications 1. -

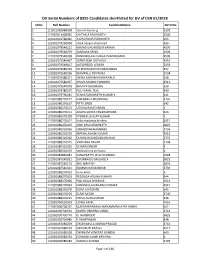

DV Sl No.S of 8255 Cen 01 2018.Xlsx

DV Serial Numbers of 8255 Candidates shortlisted for DV of CEN 01/2018 Sl No. Roll Number CandidateName DV Sl No. 1 111021092980008 ramesh kumar g 2592 2 121001013400035 CHITYALA RAVIKANTH 4506 3 121001022780082 JUJJAVARAPU SRIMANTH 635 4 121001079230008 shaik naseer ahammad 636 5 121001079540221 KAMADI JAGADEESH VARMA 4507 6 121001079540279 SANDAKA SRINU 4508 7 121001079540338 KANDREGULA DURGA PHANIKUMAR 4509 8 121001079540407 VENKATESH GUTHULA 4510 9 121001079540817 KATIKIREDDI LOKESH 2593 10 121001079580229 DILEEPKUMAR DEVARAKONDA 637 11 121001079580296 MAMPALLI PRIYANKA 3734 12 121001079580321 CHINA AKKAIAH KANKANALA 638 13 121001079580337 NAGALAKSHMI PONNURI 4511 14 121001079640078 BHUKYA DASARADH 639 15 121001079780207 PULI VIMAL TEJA 640 16 121001079790242 VENKATABHARATH KUMAR Y 641 17 121001080270122 KALLAPALLI ARUNBABU 3735 18 121001080270167 PITTA BABJI 642 19 121001080270174 UDDISA RAMCHARAN 1 20 121001080270211 ADAPA SURYA CHAKRADHARA 643 21 121001080270328 PYDIMALLA AJAY KUMAR 2 22 121001080270412 Kalla chaitanya krishna 4512 23 121001080270493 JAMI KASI VISWANATH 6822 24 121001080310065 DARABOINA RAMBABU 3736 25 121001080310176 SEPENA ASHOK KUMAR 4513 26 121001080310262 DUNNA HEMASUNDARA RAO 3737 27 121001080310275 VANDANA PAVAN 3738 28 121001080310395 DUNNA DINESH 3 29 121001080310479 vattikuti siva srinivasu 4 30 121001083840041 KANAPARTHI JAYA CHANDRA 2594 31 121001087540021 SIVUNNAIDU MUDADLA 6823 32 121001087540116 ARJI MAHESH 6824 33 121001087540321 KOMMA RAVISANKAR 3739 34 121001088270010 kona kiran 5 35 121001088270019 -

Women in Hindu Dharma- a Tribute

Women in Hindu Dharma- a Tribute Respected Ladies and Gentlemen1, Namaste! Women and the Divine Word:- Let me start my talk with a recitation from the Vedas2, the ‘Divinely Exhaled’ texts of Hindu Dharma – Profound thought was the pillow of her couch, Vision was the unguent for her eyes. Her wealth was the earth and Heaven, When Surya (the sun-like resplendent bride) went to meet her husband.3 Her mind was the bridal chariot, And sky was the canopy of that chariot. Orbs of light were the two steers that pulled the chariot, When Surya proceeded to her husband’s home!4 The close connection of women with divine revelation in Hinduism may be judged from the fact that of the 407 Sages associated with the revelation of Rigveda, twenty-one5 are women. Many of these mantras are quite significant for instance the hymn on the glorification of the Divine Speech.6 The very invocatory mantra7 of the Atharvaveda8 addresses divinity as a ‘Devi’ – the Goddess, who while present in waters, fulfills all our desires and hopes. In the Atharvaveda, the entire 14th book dealing with marriage, domestic issues etc., is attributed to a woman. Portions9 of other 19 books are also attributed to women sages10. 1 It is a Hindu tradition to address women before men in a group, out of reverence for the former. For instance, Hindu wedding invitations are normally addressed ‘To Mrs. and Mr. Smith’ and so on and not as ‘To Mr. And Mrs. Smith’ or as ‘ To Mr. and Mrs. John Smith’ or even as ‘To Mrs. -

Purusha Suktam Class-V

Purusha Suktam Class-V Note 11 PURUSHA SUKTAM When you were an infant, your father was everything for you. He provides anything you need, he protects the family, he gives you emotional support almost he is like an all-rounder for you. Similarly, you mother; she makes it possible to get what you want, almost all the works of your house are done by her, basically she is the home maker, she cooks, cleans, manages, supports, mentors and what not? Don’t you think parents are everything for you. When you grow, capable of handling things yourself, just your parents are not everything. You can see teachers, managers, principals and village Panchayat officials etc. who are just more than capable than your parents. However, there 86 Veda - B level Purusha Suktam Class-V can be no one who cares you more than your parents or parent- like caring people, is it not? Scientists of this land have visualized a grand entity which is Note capable of doing everything, all capable. It has thousands of limbs to act, eyes to watch, ears to hear etc. This is the whole message of this Purusha Sukta. Purusha Suktam colorfully narrates the properties, characteristics of Purusha (cosmic existance). The body of capable of doing everything is called Purusha in Vedas. There are many Purushas also, Vastu Purusha, Rashtra Purusha, Yajna purusha, Samaja Pursha etc. OBJECTIVES After reading this lesson, you will be able to: • recite all the mantras of Purusha sukta, • understand the basics of Purusha suktam. 11.1 PURUSHA SUKTAM Now, let us learn how to recite the Mantras of Purusha Suktam Veda - B level 87 Purusha Suktam Class-V We worship and pray to the Supreme Lord for the welfare of all beings. -

JAY MANGALAMURTI (Aarti to Shri Ganesha)

Aartis 1 JAY MANGALAMURTI (Aarti to Shri Ganesha) Sukha Karta Dukha Harta Varta Vighnachi You are the One who offers happiness and removes sorrows at the time of danger. Nurvi Purvi Prem Krupa Jayachi You offer tender lots of love and blessings Sarvangi Sunder Uti Shendurachi You have red paste on Your body Kanthi Jhalke Mal Mukta Falanchi and wear a pearl necklace. Chorus: Jai Dev., Jai Dev., Jai Mangalamurti Victory to You, most auspicious One! Darshan Matre Mana Kamana Purti Even by Your glance You fulfill the desires in our minds. Jai Dev., Jai Dev. Victory, O God! Ratna Khachita Fara Tuza Gauri Kumara The Goddess Gauri is present by Your side Chandanachi Uti Kumkum Keshara Bedecked with gems and jewellery. Hire Jadita Muguta Shobhato Bara The diamond studded crown on Your head adds to Your gracefulness, Runjhunti Nupure Charni Ghagariya The anklets on Your feet make heavenly music. Lambodar Pitambar Fanivar Bandhana I always have in mind Your long belly, Your pitambar (silk dhoti), Kundalini on Your stomach Saral Sonda Vakratunda Trinayana Your straight trunk, Your innocent face with its three eyes. Das. Ramacha Vat. Pahe Sadana The servant of Shri Rama is waiting for You in this house (body). Sankashti Pavave Nirvani Rakshave Please protect us from calamities and sorrows. O Highest amongst Gods, we bow to You! Survar Vandana Aartis 2 ARATI NIRMALA MATA Chorus: Arati Nirmala Mata ) Aarti to Mother Nirmala > Charni Thevila Me Mata ) (x2) I have surrendered to You Arati Nirmala Mata Aarti to Mother Nirmala Adi Shakti Kundalini Oh Primordial power of the Kundalini who Sarva Vishwachi Janani is the Mother of the Universe Nirguna He Rupa Tuzhe Your form is beyond the Gunas and now Zahli Saguna Tu Ata You have become Saguna (of good qualities). -

Rig Veda 5.73

1 RV 5.73 ṛṣi: paura ātreya; devatā: aśvinīkumāra; chanda: anuṣṭup; Anuvāka VI ydœ A/* Sw> p?ra/vit/ydœA?vaR/vTy!A?iñna , - - ydœva?pu/ê pu?é-uja/ydœA/Ntir?]/Aa g?tm!. 5 073 01 #/h Tya pu?é/-Ut?ma pu/ê d<sa<?is/ibæ?ta , - - v/r/Sya ya/My!AiØ?gU÷/vetu/ivò?ma -u/je. 5 073 02 $/maRNydœvpu?;e/vpu?z!c/³<rw?Sy yemwu> , - - pyR!A/Nya na÷?;a yu/ga m/ûa rja<?is dIyw> . 5 073 03 tdœ^/;uva?m!@/na k«/t<ivña/ydœva/m!Anu/òve?, - - nana?ja/tav!A?re/psa/sm!A/SmebNxu/m!@y?wu> . 5 073 04 Aa ydœva<?sU/yaR rw</itó?dœr"u/:yd</sda?, - - pir?vam!Aé/;a vyae?"&/[a v?rNt Aa/tp>?. 5 073 05 yu/vaerœAiÇ?z!icketit/nra?su/çen/cet?sa , - - "/m¡ydœva?m!Are/ps</nas?Tya/õa -u?r/{yit?. 5 073 06 %/¢aeva<?kk…/haey/iy> z&/{veyame?;us<t/in> , - - ydœva</d<sae?i-rœAiñ/naiÇ?rœnrav/vtR?it . 5 073 07 mXv?^/;um?xUyuva/éÔa/is;?i− ip/Pyu;I?, - - yt!s?mu/Ôait/p;R?w> p/Kva> p&]ae?-rNt vam!. 5 073 08 s/Tym!#dœva %?Aiñna yu/vam!Aa?÷rœmyae/-uva?, - - ta yam?n!yam/øt?ma/yam/Ú!Aa m&?¦/yÄ?ma . 5 073 09 #/ma äüa?i[/vxR?na/iñ_ya<?sNtu/z<t?ma , - - ya t]a?m/rwa? #/vavae?cam b&/hn!nm>?. 5 073 10 2 Analysis of RV 5.73 ydœ A/* Sw> p?ra/vit/ydœA?vaR/vTy!A?iñna , - - ydœva?pu/ê pu?é-uja/ydœA/Ntir?]/Aa g?tm!. -

My HANUMAN CHALISA My HANUMAN CHALISA

my HANUMAN CHALISA my HANUMAN CHALISA DEVDUTT PATTANAIK Illustrations by the author Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017 7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj New Delhi 110002 Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Illustrations Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Cover illustration: Hanuman carrying the mountain bearing the Sanjivani herb while crushing the demon Kalanemi underfoot. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-291-3770-8 First impression 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The moral right of the author has been asserted. This edition is for sale in the Indian Subcontinent only. Design and typeset in Garamond by Special Effects, Mumbai This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. To the trolls, without and within Contents Why My Hanuman Chalisa? The Text The Exploration Doha 1: Establishing the Mind-Temple Doha 2: Statement of Desire Chaupai 1: Why Monkey as God Chaupai 2: Son of Wind Chaupai 3: -

Mystical Interpretation of the Hanuman Chalisa

1 a mystical interpretation of the By#Swami#Jyo+rmayananda# Hanuman Chal!a 2 A Mystical Interpretation of the Hanuman Chalisa By Swami Jyotirmayananda Introduction by Ram-Giri The Ramayana is one of the greatest stories ever told. In this fantastic tale of the adventures of Gods and demons, humans, monkeys and bears, the fertile mind of India takes us into a journey to our own liberation. The tale engrosses the heart and mind because it is infinitely deeper than its surface narrative. It is a story told by the enlightened mind to enlighten us. It gives us a master key, a highly sophisticated psychology of the Higher Self, which transforms the reader on levels much deeper than the thinking mind. Here is a simplified summary of the mystical significance of the major elements of the Ramayana, following Swami Jyotirmayananda’s fascinating interpretation. The whole story is told with fascinating detail in Swamiji’s “Mysticism of the Ramayana,” available at yrf.org. Rama symbolizes the Supreme Self, the Ultimate Reality, the Brahman of the Upanishads. His brothers stand for sat-chit-ananda, the divine attributes—existence, consciousness, and bliss. Sita is the Divine Mother, who, through the Cosmic Mind, is the cause of the multiplicity of life. She is inseparable from Brahman. On the level of our relative existence the protagonists represent the aspects of our lives: Rama stands for the soul in the process of awakening. Lakshmana is the power of will in us. Shatrughna represents reason, and Bharata is the emotional aspect of the personality, which is channeled into devotion. -

Hindu Energies Package Descriptions

HINDU ENERGIES PACKAGE DESCRIPTIONS Ashta Lakshmi Ashta Lakshmi assists you to make energetic connection to Lakshmi and her Divine Blessings . Goddess Lakshmi means Good Luck to Hindus. The word 'Lakshmi' is derived from the Sanskrit word "Laksya", meaning 'aim' or 'goal', and she is the goddess of wealth and prosperity, both material and spiritual. Lakshmi is one of the mother goddesses and is addressed as "mata" (mother) instead of just "devi" (goddess). As a female counterpart of Lord Vishnu, Mata Lakshmi is also called 'Shri', the female energy of the Supreme Being. She is the goddess of prosperity, wealth, purity, generosity, and the embodiment of beauty, grace and charm. Lakshmi is the household goddess of most Hindu families, and a favorite of women. The Lakshmi Form: Lakshmi is depicted as a beautiful woman of golden complexion, with four hands, sitting or standing on a full-bloomed lotus and holding a lotus bud, which stands for beauty, purity and fertility. Her four hands represent the four ends of human life: dharma or righteousness, "kama" or desires, "artha" or wealth, and "moksha" or liberation from the cycle of birth and death.Cascades of gold coins are seen flowing from her hands, suggesting that those who worship her gain wealth. She always wears gold embroidered red clothes. Red symbolizes activity and the golden lining indicates prosperity. Lakshmi is the active energy of Vishnu, and also appears as Lakshmi- Narayan - Lakshmi accompanying Vishnu. Ashvins Kumaras Founder: Ramon Martinez Lopez. The Ashvins or Ashwini Kumaras (Sanskrit: अश्विê 4; aśvin-, dual aśvinau), in Hindu mythology, are divine twin horsemen in the Rigveda, sons of Saranya (daughter of vishwakarma), a goddess of the clouds and wife of Surya in his form as Vivasvat. -

Hinduism's Treatment of Untouchables

Introduction India is one of the world's great civilizations. An ancient land, vast and complex, with a full and diverse cultural heritage that has enriched the world. Extending back to the time of the world's earliest civilizations in an unbroken tradition, Indian history has seen the mingling of numerous peoples, the founding of great religions and the flourishing of science and philosophy under the patronage of grand empires. With a great reluctance to abandon traditions, India has grown a culture that is vast and rich, with an enormous body of history, legend, theology, and philosophy. With such breadth, India offers a multitude of adventuring options. Many settings are available such as the high fantasy Hindu epics or the refined British Empire in India. In these settings India allows many genres. Espionage is an example, chasing stolen nuclear material in modern India or foiling Russian imperialism in the 19th century. War is an option; one could play a soldier in the army of Alexander the Great or a proud Rajput knight willing to die before surrender. Or horror in a dangerous and alien land with ancient multi-armed gods and bloodthirsty Tantric sorcerers. Also, many styles are available, from high intrigue in the court of the Mogul Emperors to earnest quests for spiritual purity to the silliness of Mumbai "masala" movies. GURPS India presents India in all its glory. It covers the whole of Indian history, with particular emphasis on the Gupta Empire, the Moghul Empire, and the British Empire. It also details Indian mythology and the Hindu epics allowing for authentic Indian fantasy to be played. -

Kali, Untamed Goddess Power and Unleashed Sexuality: A

Journal of Asian Research Vol. 1, No. 1, 2017 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/jar Kali, Untamed Goddess Power and Unleashed Sexuality: A Study of the ‘Kalika Purana’ of Bengal Saumitra Chakravarty1* 1 Post-Graduate Studies in English, National College, Bangalore, India * Saumitra Chakravarty, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper attempts to analyse the paradox inherent in the myth of Kali, both in her iconic delineation and the rituals associated with her worship as depicted in the twelfth century Kalika Purana. The black goddess Kali breaks conventional stereotypes of feminine beauty and sexuality in Hindu goddess mythology. She is the dominant sexual partner straddling the prone Siva and the wild warrior goddess drinking demon blood. She is originally depicted as a symbol of uncontrolled fury emerging from the fair, beautiful goddess Ambika in the battle with the demons in older goddess texts. Thereafter she gains independent existence both as the dark, mysterious and sexually demanding version of the more benign and auspicious Parvati and the Primordial Goddess Power pre-dating the Hindu trinity of male gods, the Universal Mother Force which embraces both good and evil, gods and demons in the Kalika Purana. Unlike other goddess texts which emphasize Kali’s role in the battle against the demons, the Kalika Purana’s focus is on her sexuality and her darkly sensual beauty. Equally it is on the heterodoxical rituals associated with her worship involving blood and flesh offerings, wine and the use of sexual intercourse as opposed to Vedic rituals. Keywords kali, female, sexuality, primordial, goddess, paradox 1. -

Aryan and Non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the Linguistic Situation, C

Michael Witzel, Harvard University Aryan and non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the linguistic situation, c. 1900-500 B.C.. § 1. Introduction To describe and interpret the linguistic situation in Northern India1 in the second and the early first millennium B.C. is a difficult undertaking. We cannot yet read and interpret the Indus script with any degree of certainty, and we do not even know the language(s) underlying these inscriptions. Consequently, we can use only data from * archaeology, which provides, by now, a host of data; however, they are often ambiguous as to the social and, by their very nature, as to the linguistic nature of their bearers; * testimony of the Vedic texts , which are restricted, for the most part, to just one of the several groups of people that inhabited Northern India. But it is precisely the linguistic facts which often provide the only independent measure to localize and date the texts; * the testimony of the languages that have been spoken in South Asia for the past four thousand years and have left traces in the older texts. Apart from Vedic Skt., such sources are scarce for the older periods, i.e. the 2 millennia B.C. However, scholarly attention is too much focused on the early Vedic texts and on archaeology. Early Buddhist sources from the end of the first millennium B.C., as well as early Jaina sources and the Epics (with still undetermined dates of their various strata) must be compared as well, though with caution. The amount of attention paid to Vedic Skt.