Lullaby”: the Story of a Niggun1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A NATION of ANGELS Assessing the Impact of Angel Investing Across the UK

A NATION OF ANGELS Assessing the impact of angel investing across the UK January 2015 A Nation of Angels Assessing the impact of angel investing across the UK Mike Wright Enterprise Research Centre [email protected] Mark Hart Enterprise Research Centre [email protected] Kun Fu Enterprise Research Centre [email protected] Acknowledgements: The study has been conducted by the Enterprise Research Centre. The study is supported by financial contributions from Barclays, Deloitte and the BVCA and has been conducted in partnership with the UK Business Angels Association and the Centre for Entrepreneurs. Contents About Us 4 Foreword 5 Executive Summary 6 UKBAA Response to Research Findings 7 1. Introduction 8 2. Angel Background and Investing Activity 10 2.1 Who are the UK’s Angels? 10 2.2 Experience and Scale of Angel Activity 12 2.3 Where do Angels Invest in the UK? 15 2.4 What Type of Activities do Angels Invest in? 16 2.5 What use do Angels make of EIS/SEIS Tax Relief? 17 2.6 How far do Angels Co-Invest with other Sources of Finance? 18 3. Impact of Angel Investments 21 3.1 Positive Exit 21 3.2 Angels’ Perspective on their Portfolio Growth 22 3.3 Returns on Investments 25 3.4 Angel Experience and Expected Returns 29 3.5 Regional Differences in Performance of Investments 31 3.6 Investment in Social Impact Businesses 33 4. Summary and Conclusions 35 4.1 Introduction 35 4.2 Summary of Findings 35 4.3 Conclusions 36 Appendix 37 A Nation of Angels / 3 About Us The UK Business Angels Association The UK Business Angels Association (UKBAA) is the national trade association representing angel and early stage investment in the UK. -

CHERES Hailed to Be “The Best Purveyor of Authentic Ukrainian Folk

CHERES Hailed to be “the best purveyor of authentic Ukrainian folk music in the United States” by the former head of the Archive of Folk Culture at the Library of Congress, Cheres brings to life melodies from the Carpathian mountains in Western Ukraine and neighboring Eastern European countries. Since its founding in 1990 by students of the Kyiv State Conservatory in the Ukraine, the ensemble has enthralled North American audiences with their rousing renditions of folk music performed on the cymbalum, violin, woodwinds, accordion, bass, and percussion. Virtuoso musicians join spirited dancers, all donned in traditional Western Ukrainian hand-embroidered garments, to paint a vivid picture of Ukrainian folk art. The musicians, most of whom are from Halychyna in western Ukraine, are united by an artistic vision to preserve their traditions. “Cheres” is actually a little known Ukrainian term for a metal- studded leather belt formerly used as a bulletproof vest during the Middle Ages. Today, the group Cheres has adopted this Medieval protective shield as their name to symbolize the safeguarding of vanishing folk art traditions from the Carpathian mountains. This seasoned ensemble has performed in nightclubs and concerts in New York City; music festivals in the Tri-State area, including Lincoln Center’s Out of Doors Festival in 2006 and Folk Parks in 2000, as well as colleges and universities on the east coast. Cheres has appeared on television on NBC’s Weekend Today show, as well as the Food Network’s Surprise! show. Tracks from their latest CD, Cheres: From the Mountains to the Steppe” have been played on WNYC’s New Sounds program, as well as other stations in the region. -

Comparison Between Persian and English Lullabies' Themes: Songs

19895 Maryam Sedaghat et al./ Elixir Literature 65 (2013) 19895-19899 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Literature Elixir Literature 65 (2013) 19895-19899 Comparison between Persian and English Lullabies’ themes: Songs which Originate From Heart of the Culture Maryam Sedaghat 1,* and Ahmad Moinzadeh 2 1Translation Studies, University of Isfahan, Iran. 2Department of English, University of Isfahan, Iran. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The present research aimed to investigate the thematic concepts of lullabies as folk songs Received: 3 November 2013; which have passed orally through generations. The themes are hidden ideologies of lullabies Received in revised form: that carry cultural attitudes; in this regard, lullabies’ themes can reveal narrators viewpoints 2 December 2013; which originate from cultures and surrounding areas. Regarding the mentioned elements, the Accepted: 9 December 2013; themes suggested by Homayuni (2000) considered as the appropriate model for data extraction using the comparative and descriptive method. The findings showed the same Keywords themes in lullabies of both Persian and British cultures; but, in spite of similarities between Lullaby, themes, they had different ways of expression. This is to say, similarities were found in the Folklore, themes as the basic ideas and hidden layers of lullabies and differences were in their Theme, expressing ways as people attitudes. Oral tradition. © 2013 Elixir All rights reserved Introduction lullabies , are more properly song by woman, others by men” Children’s literature or juvenile literature deals with the (1972, p.1034). stories and poems for children and tries to investigate various Theme areas of this genre. Folklore is a main issue which has been Considering lullabies feminine aspect, it seems reasonable considered by researchers in children’s literature field; mother to take their thoughts into these lyrics, so, themes of lullabies sings lullabies to her child during his/her infancy and, come from their thoughts and attitudes. -

Order of Worship 12 20 2020

December 20, 2020 Fourth Sunday of Advent Order of Worship Welcome and Call to Worship Rev. Dr. David D. Young Prelude An Advent Prelude Charles Callahan Linda Repking - flute, Dr. Hyunju Hwang - organ Lighting of the Fourth Advent Candle Opening Sentences Michael Moorhead Scripture Genesis 12: 1-4 Bell Carol O Come, O Come, Emmanuel Neighborhood Brass Rings Prayer O God, who in this Advent season speaks again the word of blessing which calls us to new faith journeys, help us to have ears to hear and eyes to see the unfolding of your promise in the coming of Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen. Lighting of the Fourth Advent Candle We light the fourth Advent candle which points to promise as we remember father Abraham who heard God’s voice and was not afraid to take the first step in faithful response to God’s promised tomorrow. Scripture Reading Matthew 1: 18-25 Now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together, she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit. Her husband Joseph, being a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace, planned to dismiss her quietly. But just when he had resolved to do this, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream and said, “Joseph, son of David, do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit. She will bear a son, and you are to name him Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” All this took place to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet: “Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel,” which means “God is with us.” When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took her as his wife, but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son; and he named him Jesus.” December 20, 2020 Fourth Sunday of Advent Hymn of Preparation Angels We Have Heard on High Christopher Craig, David Sateren, Dr. -

Narration Script for Children's Pageant Imagine the Stars in the Sky, The

Narration Script for Children’s Pageant Imagine the stars in the sky, the countless constellations, the sprawling Solar System. And among it a little planet called Earth. God made all of those things, and all of the people and inhabitants of our planet. Just over two thousand years ago, God came to be with us, to show us how life should be lived. God could have chosen anywhere to be God’s home. God could have built a palace that would have made the grandeur of the most amazing palaces seem like nothing. But no. God chose a baby born among forgotten people; people who were overlooked by governments and among the poorest people. This is the story of how God came to be with us. The story begins with a young woman in her home - Mary. Unless you look a bit deeper, there is nothing particularly remarkable about Mary. She was from a town called Nazareth, and she was engaged to be married to Joseph. But, to God, she was very important. So important that God sent an angel with a message for her. The angel told Mary that she was very special and God was with her. But Mary found it hard to understand why the angel had come to see her. She was just an ordinary woman. She worried what the angel meant by the greeting. Seeing she was scared, the angel told her not to be afraid – God was very pleased with her. And she would give birth to a son. She was to call him Jesus, and he would be called the Son of God. -

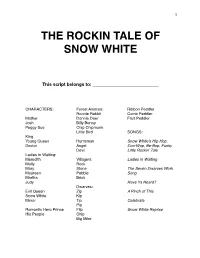

Rockin Snow White Script

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

Buffy at Play: Tricksters, Deconstruction, and Chaos

BUFFY AT PLAY: TRICKSTERS, DECONSTRUCTION, AND CHAOS AT WORK IN THE WHEDONVERSE by Brita Marie Graham A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSTIY Bozeman, Montana April 2007 © COPYRIGHT by Brita Marie Graham 2007 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Brita Marie Graham This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Linda Karell, Committee Chair Approved for the Department of English Dr. Linda Karell, Department Head Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox, Vice Provost iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it availably to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Brita Marie Graham April 2007 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In gratitude, I wish to acknowledge all of the exceptional faculty members of Montana State University’s English Department, who encouraged me along the way and promoted my desire to pursue a graduate degree. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Friday, 9/25/20 Announcements • the Jesuit's Dads Club Is Sponsoring A

Friday, 9/25/20 Announcements • The Jesuit’s Dads Club is sponsoring a Feeding Tampa Bay Mobile Pantry on Saturday, October 3rd at Hillsborough Community College. This is an opportunity for Jesuit students to volunteer alongside their fathers to help serve the hungry throughout the Tampa Bay area. The Dad’s Club is looking for 50-75 father-son pairs to help make this event a success. Interested volunteers should check the X2Vol bulletin board or email Coach Wood with any questions. • Auditions for The Masque’s fall production TWELVE INCOMPETENT JURORS will take place via Zoom today and Monday at 4pm. It is not too late to sign up, and no prior acting experience is required. To register, see the Masque Fall Play Auditions module on the Student Life Canvas page. • Yesterday, the Tiger Golf team, led by Carter Dill and Chase Johns, defeated Tampa Catholic by sweeping the Crusaders in what was their final meeting this season. Next up, the team will participate in The Lakewood Ranch Invitational on Monday. • Yesterday, the Jesuit Swimming and Diving team moved to 3-0 on the season by defeating Robinson, 145-26. Winners included: -200 Medley Relay: Liam Schindler, Nick Shaffer, Jordan Jansen, Sam Prabhakaran -200 Freestyle: Ryan Finster -200 IM: Sam Prabhakaran -50 Freestyle: Nick Shaffer -Diving: Sasha Fiola -100 Fly: Brayden Hohman -100 Freestyle: Jordan Jansen -500 Freestyle: Nick Shaffer -200 Freestyle Relay: Sam Prabhakaran, Ryan Finster, Sean Kenny, Erick Magalhaes -100 Backstroke: Aidan Clements -100 Breaststroke: Sam Prabhakaran -400 Freestyle Relay: Brayden Hohman, Liam Schindler, Jordan Jansen, Nick Shaffer The team looks to continue their dominance next Tuesday against Plant. -

Lullaby”: the Story of a Niggun1

“Lullaby”: The Story of a Niggun1 MICHAEL BECKERMAN AND NAOMI TADMOR Introduction In the winter of 1943, a song was performed in the Terezín Ghetto. It was an art song with a Hebrew text, yet its melody had also featured as a folk song, a pop tune, and a wordless vocalization; later, it would become a religious hymn. This article seeks to uncover the story of this tune: how it emerged, how it acquired a text, how it got to Terezín, how it was treated there, and what meanings can be drawn from its manifestations. The piece in question is Gideon Klein’s “Lullaby.” Our inquiry started as we noted an anomaly, a disagreement between recordings. At a key point in the composition, we realized that two performers sing different pitches, which is not unusual in many song traditions, but is entirely atypical of a notated art song. Example 1a: Excerpt from Isabelle Ganz’s recording of Gideon Klein’s “Lullaby”2 Example 1b: Excerpt from Wolfgang Holzmair’s recording of Gideon Klein’s “Lullaby.”3 Listen at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/mp.9460447.0010.101 We wondered, how could this difference be explained? Was one version mistaken? If so, which one, and why did the mistake occur? Does it have any significance? While attempting to answer these questions, we found ourselves embarking on a scholarly pilgrimage, which took us from a shtetl-like community within a Russian imperial city, where the tune originated as a Hasidic niggun, to Anglo-Palestine in the 1930s and 40s, where it was transformed, and from there further to the European diaspora in the 1940s, to countries such as England and Poland, and then to Nazi Germany, where the version on which Klein’s song was based, was created; from there we crossed the Atlantic to New York, where a version of the original niggun was first notated, and then back to Terezín. -

Go, Go Gabriel – Programme Notes

Go, Go Gabriel Synopsis and Songs. Act One • Go, Go Gabriel The Angel Gabriel hears that he has a special mission. • You’ve Got To Tell Her Gabe learns that he needs to tell Mary that she will have a very special baby. • Have I Got News For You Gabe tells Mary the amazing news – but will she believe him? • How Do I Tell Joe? Mary wonders how Joseph will react to the news. • The Little Problem Mary tries to explain to Joseph. He doesn’t believe her! • You’re Easily Hurt Joe is upset and it is up to Gabe to convince him that Mary is telling the truth. • Go, Go Gabriel (Reprise) Gabe has helped Joe to understand what is going on, and Mary and Joseph are married. However, Gabe still has more work to do. • They’re Having A Baby The townspeople react to the news that Mary and Joe are expecting a baby. • Caesar Wants His Pound of Flesh A census is called and Joe reveals that they will have to travel to Bethlehem. • We’re Here Mary and Joseph arrive in Bethlehem. Mary is tired from the journey, so Joseph sings her to sleep. • No Room At The Inn Joseph goes in search of a bed for the night, but this proves more difficult than he thought. Eventually the problem is solved and the baby is born. Act Two • Come On! The Angels hurry to tell the shepherds the wonderful news about the baby. • Myrrh Sir The Angels visit the Three Kings, and their journey to Bethlehem begins.