Lepidothyris Fernandi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 60, Number 1, Pp

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, volume 60, number 1, pp. 190–201 doi:10.1093/icb/icaa015 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology SYMPOSIUM Convergent Evolution of Elongate Forms in Craniates and of Locomotion in Elongate Squamate Reptiles Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-abstract/60/1/190/5813730 by Clark University user on 24 July 2020 Philip J. Bergmann ,* Sara D. W. Mann,* Gen Morinaga,1,*,† Elyse S. Freitas‡ and Cameron D. Siler‡ *Department of Biology, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA; †Department of Integrative Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA; ‡Department of Biology and Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA From the symposium “Long Limbless Locomotors: The Mechanics and Biology of Elongate, Limbless Vertebrate Locomotion” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology January 3–7, 2020 at Austin, Texas. 1E-mail: [email protected] Synopsis Elongate, snake- or eel-like, body forms have evolved convergently many times in most major lineages of vertebrates. Despite studies of various clades with elongate species, we still lack an understanding of their evolutionary dynamics and distribution on the vertebrate tree of life. We also do not know whether this convergence in body form coincides with convergence at other biological levels. Here, we present the first craniate-wide analysis of how many times elongate body forms have evolved, as well as rates of its evolution and reversion to a non-elongate form. We then focus on five convergently elongate squamate species and test if they converged in vertebral number and shape, as well as their locomotor performance and kinematics. -

The Herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and Lower Cuando River Catchments of South-Eastern Angola

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 10(2) [Special Section]: 6–36 (e126). The herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and lower Cuando river catchments of south-eastern Angola 1,2,*Werner Conradie, 2Roger Bills, and 1,3William R. Branch 1Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, SOUTH AFRICA 2South African Institute for Aquatic Bio- diversity, P/Bag 1015, Grahamstown 6140, SOUTH AFRICA 3Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P O Box 77000, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 6031, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—Angola’s herpetofauna has been neglected for many years, but recent surveys have revealed unknown diversity and a consequent increase in the number of species recorded for the country. Most historical Angola surveys focused on the north-eastern and south-western parts of the country, with the south-east, now comprising the Kuando-Kubango Province, neglected. To address this gap a series of rapid biodiversity surveys of the upper Cubango-Okavango basin were conducted from 2012‒2015. This report presents the results of these surveys, together with a herpetological checklist of current and historical records for the Angolan drainage of the Cubango, Cuito, and Cuando Rivers. In summary 111 species are known from the region, comprising 38 snakes, 32 lizards, five chelonians, a single crocodile and 34 amphibians. The Cubango is the most western catchment and has the greatest herpetofaunal diversity (54 species). This is a reflection of both its easier access, and thus greatest number of historical records, and also the greater habitat and topographical diversity associated with the rocky headwaters. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care Sheets Are Often An

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care sheets are often an excellent starting point for learning more about the biology and husbandry of a given species, including their housing/enclosure requirements, temperament and handling, diet , and other aspects of care. MAHS itself has created many such care sheets for a wide range of reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates we believe to have straightforward care requirements, and thus make suitable family and beginner’s to intermediate level pets. Some species with much more complex, difficult to meet, or impracticable care requirements than what can be adequately explained in a one page care sheet may be multiple pages. We can also provide additional links, resources, and information on these species we feel are reliable and trustworthy if requested. If you would like to request a copy of a care sheet for any of the species listed below, or have a suggestion for an animal you don’t see on our list, contact us to let us know! Unfortunately, for liability reasons, MAHS is unable to create or publish care sheets for medically significant venomous species. This includes species in the families Crotilidae, Viperidae, and Elapidae, as well as the Helodermatidae (the Gila Monsters and Mexican Beaded Lizards) and some medically significant rear fanged Colubridae. Those that are serious about wishing to learn more about venomous reptile husbandry that cannot be adequately covered in one to three page care sheets should take the time to utilize all available resources by reading books and literature, consulting with, and working with an experienced and knowledgeable mentor in order to learn the ropes hands on. -

Abstracts Part 1

375 Poster Session I, Event Center – The Snowbird Center, Friday 26 July 2019 Maria Sabando1, Yannis Papastamatiou1, Guillaume Rieucau2, Darcy Bradley3, Jennifer Caselle3 1Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, Chauvin, LA, USA, 3University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA Reef Shark Behavioral Interactions are Habitat Specific Dominance hierarchies and competitive behaviors have been studied in several species of animals that includes mammals, birds, amphibians, and fish. Competition and distribution model predictions vary based on dominance hierarchies, but most assume differences in dominance are constant across habitats. More recent evidence suggests dominance and competitive advantages may vary based on habitat. We quantified dominance interactions between two species of sharks Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos and Carcharhinus melanopterus, across two different habitats, fore reef and back reef, at a remote Pacific atoll. We used Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) to observe dominance behaviors and quantified the number of aggressive interactions or bites to the BRUVs from either species, both separately and in the presence of one another. Blacktip reef sharks were the most abundant species in either habitat, and there was significant negative correlation between their relative abundance, bites on BRUVs, and the number of grey reef sharks. Although this trend was found in both habitats, the decline in blacktip abundance with grey reef shark presence was far more pronounced in fore reef habitats. We show that the presence of one shark species may limit the feeding opportunities of another, but the extent of this relationship is habitat specific. Future competition models should consider habitat-specific dominance or competitive interactions. -

Activity Patterns and Habitat Selection in a Population of the African Fire Skink (Lygosoma Fernandi) from the Niger Delta, Nigeria

HERPETOLOGICAL JOURNAL 19: 207–211, 2009 Activity patterns and habitat selection in a population of the African fire skink (Lygosoma fernandi) from the Niger Delta, Nigeria Godfrey C. Akani1, Luca Luiselli2, Anthony E. Ogbeibu3, Mike Uwaegbu4 & Nwabueze Ebere1 1Department of Applied and Environmental Biology, Rivers State University of Science & Technology, Nigeria 2Institute of Environmental Studies DEMETRA, Rome, Italy 3Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, University of Benin, Nigeria 4Department of Zoology, Ambrose Alli University, Nigeria The African fire skink, Lygosoma fernandi, is a poorly known, large scincid species inhabiting the rainforests of central and western Africa. Aspects of its field ecology (daily and seasonal activity patterns and habitat selection) were studied at a coastal site in southeastern Nigeria. Skinks were studied by both pitfall traps and visual encounter survey techniques for a total of 40 field days (20 in the dry and 20 in the wet season) by nine researchers. Over 98% of skinks (n=106) were active between 1715 and 1830, while only 2% were found out of their burrow earlier in the day. Above-ground activity was significantly more intense during the wet season. Lygosoma fernandi selected habitat types regardless of their relative availability in the field, and showed a clear preference for swamp forest and lowland forest patches. Mangrove swamps were, on the other hand, actively avoided. Key words: ecology, morphometry, Scincidae, West Africa INTRODUCTION (Luiselli et al., 2002). In some localities of southern Ni- geria, L. fernandi is regarded as an omen or totem, and is he African fire skink, Lygosoma (= Lepidothyris, = erroneously thought to be venomous by rural people. -

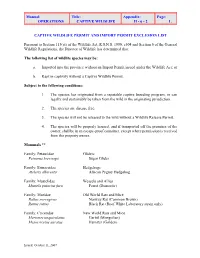

Captive Wildlife Exclusion List

Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 1. CAPTIVE WILDLIFE PERMIT AND IMPORT PERMIT EXCLUSION LIST Pursuant to Section 113(at) of the Wildlife Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c504 and Section 6 of the General Wildlife Regulations, the Director of Wildlife has determined that: The following list of wildlife species may be: a. Imported into the province without an Import Permit issued under the Wildlife Act; or b. Kept in captivity without a Captive Wildlife Permit. Subject to the following conditions: 1. The species has originated from a reputable captive breeding program, or can legally and sustainably be taken from the wild in the originating jurisdiction. 2. The species are disease free. 3. The species will not be released to the wild without a Wildlife Release Permit. 4. The species will be properly housed, and if transported off the premises of the owner, shall be in an escape-proof container, except where permission is received from the property owner. Mammals ** Family: Petauridae Gliders Petuarus breviceps Sugar Glider Family: Erinaceidae Hedgehogs Atelerix albiventis African Pygmy Hedgehog Family: Mustelidae Weasels and Allies Mustela putorius furo Ferret (Domestic) Family: Muridae Old World Rats and Mice Rattus norvegicus Norway Rat (Common Brown) Rattus rattus Black Rat (Roof White Laboratory strain only) Family: Cricetidae New World Rats and Mice Meriones unquiculatus Gerbil (Mongolian) Mesocricetus auratus Hamster (Golden) Issued: October 11, 2007 Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 2. Family: Caviidae Guinea Pigs and Allies Cavia porcellus Guinea Pig Family: Chinchillidae Chinchillas Chincilla laniger Chinchilla Family: Leporidae Hares and Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus European Rabbit (domestic strain only) Birds Family: Psittacidae Parrots Psittaciformes spp.* All parrots, parakeets, lories, lorikeets, cockatoos and macaws. -

Morphology, Taxonomy and Life Cycles of Some Saurian

MORPHOLOGY, TAXONOMY AND LIFE CYCLES OF SOME SAURIAN HAEMATOZOA by Keith Robert Wallbanks B.Sc. (Lond.) A.R.C.S. 1982 A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London Department of Pure and Applied Biology Imperial College Silwood Park Ascot Berkshire ii TO MY MOTHER AND FATHER WITH GRATITUDE AND LOVE iii Abstract The trypanosomes and Leishmania parasites of lizards are reviewed. The development of Trypanosoma platydactyli in two sandfly species, Sergentomyia minuta and Phlehotomus papatasi and in in vitro culture was followed. In sandflies the blood trypomastigotes passed through amastigote, epimastigote and promastigote phases in the midgut of the fly before developing into short, slender, non-dividing trypomastigotes in the mid- and hind-gut. These short trypomastigotes are presumed to be the infective metatrypomastigotes. In axenic culture T. platydactyli passed through amastigote and epimastigote phases into a promastigote phase. The promastigote phase was very stable and attempts to stimulate -the differentiation of promastigotes to epi- or trypo-mastigotes, by changing culture media, pH values and temperature failed. The trypanosome origin of the promastigotes was proved by the growth of promastigotes in cultures from a cloned blood trypomastigote. The resultant promastigote cultures were identical in general morphology, ultrastructure and the electrophoretic mobility of 8 enzymes to those previously considered to be Leishmania tarentolae. T. platydactyli and L. tarentolae are synonymised and the present status of saurian Leishmania parasites is discussed. Promastigote cultures of T. platydactyli formed intracellular amastigotes. in mouse macrophages, lizard monocytes and lizard kidney cells in vitro. The parasites were rapidly destroyed by mouse macrophages jlii vivo and in vitro at 37°C. -

Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021, W-13.12 Reg 5

1 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 W-13.12 REG 5 The Captive Wildlife Regulations, 2021 being Chapter W-13.12 Reg 5 (effective June 1, 2021). NOTE: This consolidation is not official. Amendments have been incorporated for convenience of reference and the original statutes and regulations should be consulted for all purposes of interpretation and application of the law. In order to preserve the integrity of the original statutes and regulations, errors that may have appeared are reproduced in this consolidation. 2 W-13.12 REG 5 CAPTIVE WILDLIFE, 2021 Table of Contents PART 1 PART 5 Preliminary Matters Zoo Licences and Travelling Zoo Licences 1 Title 38 Definition for Part 2 Definitions and interpretation 39 CAZA standards 3 Application 40 Requirements – zoo licence or travelling zoo licence PART 2 41 Breeding and release Designations, Prohibitions and Licences PART 6 4 Captive wildlife – designations Wildlife Rehabilitation Licences 5 Prohibition – holding unlisted species in captivity 42 Definitions for Part 6 Prohibition – holding restricted species in captivity 43 Standards for wildlife rehabilitation 7 Captive wildlife licences 44 No property acquired in wildlife held for 8 Licence not required rehabilitation 9 Application for captive wildlife licence 45 Requirements – wildlife rehabilitation licence 10 Renewal 46 Restrictions – wildlife not to be rehabilitated 11 Issuance or renewal of licence on terms and conditions 47 Wildlife rehabilitation practices 12 Licence or renewal term PART 7 Scientific Research Licences 13 Amendment, suspension, -

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda

Nationally Threatened Species for Uganda National Red List for Uganda for the following Taxa: Mammals, Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Butterflies, Dragonflies and Vascular Plants JANUARY 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The research team and authors of the Uganda Redlist comprised of Sarah Prinsloo, Dr AJ Plumptre and Sam Ayebare of the Wildlife Conservation Society, together with the taxonomic specialists Dr Robert Kityo, Dr Mathias Behangana, Dr Perpetra Akite, Hamlet Mugabe, and Ben Kirunda and Dr Viola Clausnitzer. The Uganda Redlist has been a collaboration beween many individuals and institutions and these have been detailed in the relevant sections, or within the three workshop reports attached in the annexes. We would like to thank all these contributors, especially the Government of Uganda through its officers from Ugandan Wildlife Authority and National Environment Management Authority who have assisted the process. The Wildlife Conservation Society would like to make a special acknowledgement of Tullow Uganda Oil Pty, who in the face of limited biodiversity knowledge in the country, and specifically in their area of operation in the Albertine Graben, agreed to fund the research and production of the Uganda Redlist and this report on the Nationally Threatened Species of Uganda. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREAMBLE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................... -

Thiel, C. 2011. Ecology and Population Status of the Serval Leptailurus Serval in Zambia

Thiel, C. 2011. Ecology and population status of the serval Leptailurus serval in Zambia. Thesis: 1-294. Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn. 2011. Keywords: 1ET/1KE/1TZ/1UG/1ZA/1ZM/diet/disease/distribution/ecology/habitat/habitat preference/Leptailurus serval/parasites/population status/prey/prey availability/serval/status Abstract: Little is known about the Serval's ecology, its needs and population status. This thesis is providing a new and detailed groundwork on this elusive felid species. The study was conducted between 2006 and 2008 in Zambia, with the focus area being Luambe National Park (LNP) in the Luangwa Valley. Using transect line walking, signs of Serval presence (faeces, spoor and sightings) were recorded. Analyses of these records revealed new information on the diet, habitat preferences, the distribution within LNP, and parasite composition in faecal samples. The most studied fact on Servals found in literature is their diet, through scats analyses, observations and stomach analyses. Faeces analyses of this thesis supported the previous studies' findings that the Leptailurus serval is a rodent hunter. But besides that, they also prey extensively on birds, on reptiles, and on arthropods. A diet breadth of 0.5 also indicates a more opportunistic lifestyle. People associate Servals with grasslands and wetlands, but this study proved the Servals to use also thickets and riverine woodland. This felid needs water resources nearby and a certain degree of cover, whether it is grass or thickets/bushes. Closed forests with little ground cover are less preferred or even avoided habitats. parasites of Servals were never analysed up to now. This analysis revealed Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Haemaphysalis leachi, both so-called 'Dog Ticks', to be the most common tick of Leptailurus serval. -

Preliminary Herpetological Survey of Ngonye Falls and Surrounding Regions in South-Western Zambia 1,2,*Darren W

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 11(1) [Special Section]: 24–43 (e148). Preliminary herpetological survey of Ngonye Falls and surrounding regions in south-western Zambia 1,2,*Darren W. Pietersen, 3Errol W. Pietersen, and 4,5Werner Conradie 1Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, SOUTH AFRICA 2Research Associate, Herpetology Section, Department of Vertebrates, Ditsong National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 413, Pretoria, 0001, SOUTH AFRICA 3P.O. Box 1514, Hoedspruit, 1380, SOUTH AFRICA 4Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. Box 13147, Humewood, 6013, SOUTH AFRICA 5School of Natural Resource Management, George Campus, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, George, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—The herpetofauna of Zambia has been relatively well-studied, although most surveys were conducted decades ago. In western Zambia in particular, surveys were largely restricted to a few centers, particularly those along the Zambezi River. We here report on the herpetofauna of the Ngonye Falls and surrounding regions in south-western Zambia. We recorded 18 amphibian, one crocodile, two chelonian, 22 lizard, and 19 snake species, although a number of additional species are expected to occur in the region based on their known distribution and habitat preferences. We also provide three new reptile country records for Zambia (Long-tailed Worm Lizard, Dalophia longicauda, Anchieta’s Worm Lizard, Monopeltis anchietae, and Zambezi Rough-scaled Lizard, Ichnotropis grandiceps), and report on the second specimen of Schmitz’s Legless Skink, Acontias schmitzi, a species described in 2012 and until now known only from the holotype. This record also represents a 140 km southward range extension for the species.