Trade-Offs Between Burrowing and Biting Force in Fossorial Scincid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List Common Name Scientific Name Status Snakes Cape cobra Naja nivea Puffadder Bitis arietans Albany adder Bitis albanica very rare Night adder Causes rhombeatus Bergadder Bitis atropos Horned adder Bitis cornuta Boomslang Dispholidus typus Rinkhals Hemachatus hemachatus Herald/Red-lipped snake Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Olive house snake Lamprophis inornatus Night snake Lamprophis aurora Brown house snake Lamprophis fuliginosus fuliginosus Speckled house snake Homoroselaps lacteus Wolf snake Lycophidion capense Spotted harlequin snake Philothamnus semivariegatus Speckled bush snake Bitis atropos Green water snake Philothamnus hoplogaster Natal green watersnake Philothamnus natalensis occidentalis Shovel-nosed snake Prosymna sundevalli Mole snake Pseudapsis cana Slugeater Duberria lutrix lutrix Common eggeater Dasypeltis scabra scabra Dappled sandsnake Psammophis notosticus Crossmarked sandsnake Psammophis crucifer Black-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus laevissimus Common/Red-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus rufulus Tortoises/terrapins Angulate tortoise Chersina angulata Leopard tortoise Geochelone pardalis Green parrot-beaked tortoise Homopus areolatus Marsh/Helmeted terrapin Pelomedusa subrufa Tent tortoise Psammobates tentorius Lizards/geckoes/skinks Rock Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus niloticus niloticus Water Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus exanthematicus albigularis Tasman's Girdled Lizard Cordylus tasmani Cape Girdled Lizard Cordylus cordylus Southern Rock Agama Agama atra Burrowing -

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 60, Number 1, Pp

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, volume 60, number 1, pp. 190–201 doi:10.1093/icb/icaa015 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology SYMPOSIUM Convergent Evolution of Elongate Forms in Craniates and of Locomotion in Elongate Squamate Reptiles Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-abstract/60/1/190/5813730 by Clark University user on 24 July 2020 Philip J. Bergmann ,* Sara D. W. Mann,* Gen Morinaga,1,*,† Elyse S. Freitas‡ and Cameron D. Siler‡ *Department of Biology, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA; †Department of Integrative Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA; ‡Department of Biology and Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA From the symposium “Long Limbless Locomotors: The Mechanics and Biology of Elongate, Limbless Vertebrate Locomotion” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology January 3–7, 2020 at Austin, Texas. 1E-mail: [email protected] Synopsis Elongate, snake- or eel-like, body forms have evolved convergently many times in most major lineages of vertebrates. Despite studies of various clades with elongate species, we still lack an understanding of their evolutionary dynamics and distribution on the vertebrate tree of life. We also do not know whether this convergence in body form coincides with convergence at other biological levels. Here, we present the first craniate-wide analysis of how many times elongate body forms have evolved, as well as rates of its evolution and reversion to a non-elongate form. We then focus on five convergently elongate squamate species and test if they converged in vertebral number and shape, as well as their locomotor performance and kinematics. -

The Herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and Lower Cuando River Catchments of South-Eastern Angola

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 10(2) [Special Section]: 6–36 (e126). The herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and lower Cuando river catchments of south-eastern Angola 1,2,*Werner Conradie, 2Roger Bills, and 1,3William R. Branch 1Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, SOUTH AFRICA 2South African Institute for Aquatic Bio- diversity, P/Bag 1015, Grahamstown 6140, SOUTH AFRICA 3Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P O Box 77000, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 6031, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—Angola’s herpetofauna has been neglected for many years, but recent surveys have revealed unknown diversity and a consequent increase in the number of species recorded for the country. Most historical Angola surveys focused on the north-eastern and south-western parts of the country, with the south-east, now comprising the Kuando-Kubango Province, neglected. To address this gap a series of rapid biodiversity surveys of the upper Cubango-Okavango basin were conducted from 2012‒2015. This report presents the results of these surveys, together with a herpetological checklist of current and historical records for the Angolan drainage of the Cubango, Cuito, and Cuando Rivers. In summary 111 species are known from the region, comprising 38 snakes, 32 lizards, five chelonians, a single crocodile and 34 amphibians. The Cubango is the most western catchment and has the greatest herpetofaunal diversity (54 species). This is a reflection of both its easier access, and thus greatest number of historical records, and also the greater habitat and topographical diversity associated with the rocky headwaters. -

Project Name

PROPOSED LAGUNA BAY RESORT AND VISITORS CENTRE JEFFREYS BAY, EASTERN CAPE SPECIALIST REPORT - ECOLOGICAL Prepared for: Berkowitz & Associates 100 William Road Norwood 2192 Prepared by: Coastal & Environmental Services GRAHAMSTOWN P.O. Box 934 Grahamstown, 6140 046 622 2364 Also in East London www.cesnet.co.za DECEMBER 2010 This Report should be sited as follows: Coastal & Environmental Services, December 2010: Laguna Bay Resort and Visitors Centre, Jeffrey’s Bay, Eastern Cape, Ecological Assessment, CES, Grahamstown. COPYRIGHT INFORMATION This document contains intellectual property and propriety information that is protected by copyright in favour of Coastal & Environmental Services and the specialist consultants. The document may therefore not be reproduced, used or distributed to any third party without the prior written consent of Coastal & Environmental Services. This document is prepared exclusively for submission to Berkowitz & Associates, and is subject to all confidentiality, copyright and trade secrets, rules intellectual property law and practices of South Africa. Specialist Ecological Report – December 2010 THE PROJECT TEAM Prof Roy Lubke, Botanical Specialist, been involved in the study and research of coastal dune systems in South Africa, specialising in the rehabilitation of dune systems. These studies include availability of plant pathogens and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza in dune systems and on dune plants; plant succession and dynamics of dune systems; the effects of potentially invasive species on dune systems and the restoration of dune systems. Professor Lubke has held CSIR and FRD national programme funded projects in South Africa, and has managed European Union-funded projects on marram grass and the use of indigenous species for dune rehabilitation, in association with colleagues from the Netherlands, the United Kingom and Botswana. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Scincella Lateralis)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 7(2): 109–114. Submitted: 30 January 2012; Accepted: 30 June 2012; Published: 10 September 2012. SEXUAL DIMORPHISM IN HEAD SIZE IN THE LITTLE BROWN SKINK (SCINCELLA LATERALIS) 1 BRIAN M. BECKER AND MARK A. PAULISSEN Department of Natural Sciences, Northeastern State University, Tahlequah, Oklahoma 74464, USA 1Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Many species of skinks show pronounced sexual dimorphism in that males have larger heads relative to their size than females. This can occur in species in which males have greater body length and show different coloration than females, such as several species of the North American genus Plestiodon, but can also occur in species in which males and females have the same body length, or species in which females are larger than males. Another North American skink species, Scincella lateralis, does not exhibit obvious sexual dimorphism. However, behavioral data suggest sexual differences in head size might be expected because male S. lateralis are more aggressive than females and because these aggressive interactions often involve biting. In this study, we measured snout-to-vent length and head dimensions of 31 male and 35 female S. lateralis from northeastern Oklahoma. Females were slightly larger than males, but males had longer, wider, and deeper heads for their size than females. Sexual dimorphism in head size may be the result of sexual selection favoring larger heads in males in male-male contests. However, male S. lateralis are also aggressive to females and larger male head size may give males an advantage in contests with females whose body sizes are equal to or larger than theirs. -

Annotated Checklist and Provisional Conservation Status of Namibian Reptiles

Annotated Checklist - Reptiles Page 1 ANNOTATED CHECKLIST AND PROVISIONAL CONSERVATION STATUS OF NAMIBIAN REPTILES MICHAEL GRIFFIN BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM PRIVATE BAG 13306 WINDHOEK NAMIBIA Annotated Checklist - Reptiles Page 2 Annotated Checklist - Reptiles Page 3 CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 5 INTRODUCTION 5 METHODS AND DEFINITIONS 6 SPECIES ACCOUNTS Genus Crocodylus Nile Crocodile 11 Pelomedusa Helmeted Terrapin 11 Pelusios Hinged Terrapins 12 Geochelone Leopard Tortoise 13 Chersina Bowsprit Tortoise 14 Homopus Nama Padloper 14 Psammobates Tent Tortoises 15 Kinixys Hinged Tortoises 16 Chelonia GreenTurtle 16 Lepidochelys Olive Ridley Turtle 17 Dermochelys Leatherback Turtle 17 Trionyx African Soft-shelled Turtle 18 Afroedura Flat Geckos 19 Goggia Dwarf Leaf-toed Geckos 20 Afrogecko Marbled Leaf-toed Gecko 21 Phelsuma Namaqua Day Gecko 22 Lygodactylus Dwarf Geckos 23 Rhoptropus Namib Day Geckos 25 Chondrodactylus Giant Ground Gecko 27 Colopus Kalahari Ground Gecko 28 Palmatogecko Web-footed Geckos 28 Pachydactylus Thick-toed Geckos 29 Ptenopus Barking Geckos 39 Narudasia Festive Gecko 41 Hemidactylus Tropical House Geckos 41 Agama Ground Agamas 42 Acanthocercus Tree Agama 45 Bradypodion Dwarf Chameleons 46 Chamaeleo Chameleons 47 Acontias Legless Skinks 48 Typhlosaurus Blind Legless Skinks 48 Sepsina Burrowing Skinks 50 Scelotes Namibian Dwarf Burrowing Skink 51 Typhlacontias Western Burrowing Skinks 51 Lygosoma Sundevall’s Writhing Skink 53 Mabuya Typical Skinks 53 Panaspis Snake-eyed Skinks 60 Annotated -

Abstracts Part 1

375 Poster Session I, Event Center – The Snowbird Center, Friday 26 July 2019 Maria Sabando1, Yannis Papastamatiou1, Guillaume Rieucau2, Darcy Bradley3, Jennifer Caselle3 1Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, Chauvin, LA, USA, 3University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA Reef Shark Behavioral Interactions are Habitat Specific Dominance hierarchies and competitive behaviors have been studied in several species of animals that includes mammals, birds, amphibians, and fish. Competition and distribution model predictions vary based on dominance hierarchies, but most assume differences in dominance are constant across habitats. More recent evidence suggests dominance and competitive advantages may vary based on habitat. We quantified dominance interactions between two species of sharks Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos and Carcharhinus melanopterus, across two different habitats, fore reef and back reef, at a remote Pacific atoll. We used Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) to observe dominance behaviors and quantified the number of aggressive interactions or bites to the BRUVs from either species, both separately and in the presence of one another. Blacktip reef sharks were the most abundant species in either habitat, and there was significant negative correlation between their relative abundance, bites on BRUVs, and the number of grey reef sharks. Although this trend was found in both habitats, the decline in blacktip abundance with grey reef shark presence was far more pronounced in fore reef habitats. We show that the presence of one shark species may limit the feeding opportunities of another, but the extent of this relationship is habitat specific. Future competition models should consider habitat-specific dominance or competitive interactions. -

Fauna of Australia 2A

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 26. BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYLOGENY OF THE SQUAMATA Mark N. Hutchinson & Stephen C. Donnellan 26. BIOGEOGRAPHY AND PHYLOGENY OF THE SQUAMATA This review summarises the current hypotheses of the origin, antiquity and history of the order Squamata, the dominant living reptile group which comprises the lizards, snakes and worm-lizards. The primary concern here is with the broad relationships and origins of the major taxa rather than with local distributional or phylogenetic patterns within Australia. In our review of the phylogenetic hypotheses, where possible we refer principally to data sets that have been analysed by cladistic methods. Analyses based on anatomical morphological data sets are integrated with the results of karyotypic and biochemical data sets. A persistent theme of this chapter is that for most families there are few cladistically analysed morphological data, and karyotypic or biochemical data sets are limited or unavailable. Biogeographic study, especially historical biogeography, cannot proceed unless both phylogenetic data are available for the taxa and geological data are available for the physical environment. Again, the reader will find that geological data are very uncertain regarding the degree and timing of the isolation of the Australian continent from Asia and Antarctica. In most cases, therefore, conclusions should be regarded very cautiously. The number of squamate families in Australia is low. Five of approximately fifteen lizard families and five or six of eleven snake families occur in the region; amphisbaenians are absent. Opinions vary concerning the actual number of families recognised in the Australian fauna, depending on whether the Pygopodidae are regarded as distinct from the Gekkonidae, and whether sea snakes, Hydrophiidae and Laticaudidae, are recognised as separate from the Elapidae. -

The Herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and Lower Cuando River Catchments of South-Eastern Angola

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 10(2) [Special Section]: 6–36 (e126). The herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and lower Cuando river catchments of south-eastern Angola 1,2,*Werner Conradie, 2Roger Bills, and 1,3William R. Branch 1Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, SOUTH AFRICA 2South African Institute for Aquatic Bio- diversity, P/Bag 1015, Grahamstown 6140, SOUTH AFRICA 3Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P O Box 77000, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 6031, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—Angola’s herpetofauna has been neglected for many years, but recent surveys have revealed unknown diversity and a consequent increase in the number of species recorded for the country. Most historical Angola surveys focused on the north-eastern and south-western parts of the country, with the south-east, now comprising the Kuando-Kubango Province, neglected. To address this gap a series of rapid biodiversity surveys of the upper Cubango-Okavango basin were conducted from 2012‒2015. This report presents the results of these surveys, together with a herpetological checklist of current and historical records for the Angolan drainage of the Cubango, Cuito, and Cuando Rivers. In summary 111 species are known from the region, comprising 38 snakes, 32 lizards, five chelonians, a single crocodile and 34 amphibians. The Cubango is the most western catchment and has the greatest herpetofaunal diversity (54 species). This is a reflection of both its easier access, and thus greatest number of historical records, and also the greater habitat and topographical diversity associated with the rocky headwaters. -

Greater Waterberg Landscape: 74 Species of Reptiles Known Or Expected to Occur

Greater Waterberg Landscape: 74 species of reptiles known or expected to occur: TORTOISES & Leopard Tortoise Stigmochelys pardalis TERRAPINS Kalahari Tent Tortoise Psammobates oculiferus Marsh/Helmeted Terrapin Pelomedusa subrufa SNAKES Blind Snakes Boyle’s Beaked Blind Snake Rhinotyphlops boylei Schinz’s Beaked Blind Snake Rhinotyphlops schinzi Schlegel’s Beaked Blind Snake Rhinotyphlops schlegelii Thread Snakes Peter’s Thread Snake Leptotyphlops scutifrons Pythons Southern African Python Python natalensis Burrowing Asps Bibron’s Burrowing Asp Atractaspis bibronii Purple Glossed Kalahari Purple-glossed Snake Amblyodipsas ventrimaculata Snakes Quill Snouted Bicoloured Quill-snouted Snake Xenocalamus bicolor Snakes Elongate Quill-snouted Snake Xenocalamus mechowii Typical Snakes Brown House Snake Lamprophis fuliginosus Cape Wolf Snake Lycophidion capense Angola File Snake Mehelya vernayi Mole Snake Pseudaspis cana Two-striped Shovel-snout Prosymna bivittata South-western Shovel-snout Prosymna frontalis Viperine Bark Snake Hemirhagerrhis viperinus Dwarf Beaked Snake Dipsina multimaculata Striped Skaapsteker Psammophylax tritaeniatus Karoo Sand Snake Psammophis notostictus Namib Sand Snake Psammophis leightoni trinasalis Jalla’s Sand Snake Psammophis jallae Stripe-bellied Sand Snake Psammophis subtaeniatus Leopard and Short-snouted Psammophis brevirostris leopardinus Grass Snakes Olive grass snake Psammophis mossambicus Spotted Bush Snake Philothamnus semivariegatus Common/Rhombic Egg Eater Dasypeltis scabra Eastern Tiger Snake Telescopus -

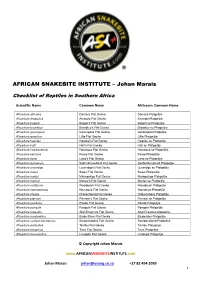

Johan Marais

AFRICAN SNAKEBITE INSTITUTE – Johan Marais Checklist of Reptiles in Southern Africa Scientific Name Common Name Afrikaans Common Name Afroedura africana Damara Flat Gecko Damara Platgeitjie Afroedura amatolica Amatola Flat Gecko Amatola Platgeitjie Afroedura bogerti Bogert's Flat Gecko Bogert se Platgeitjie Afroedura broadleyi Broadley’s Flat Gecko Broadley se Platgeitjie Afroedura gorongosa Gorongosa Flat Gecko Gorongosa Platgeitjie Afroedura granitica Lillie Flat Gecko Lillie Platgeitjie Afroedura haackei Haacke's Flat Gecko Haacke se Platgeitjie Afroedura halli Hall's Flat Gecko Hall se Platgeitjie Afroedura hawequensis Hawequa Flat Gecko Hawequa se Platgeitjie Afroedura karroica Karoo Flat Gecko Karoo Platgeitjie Afroedura langi Lang's Flat Gecko Lang se Platgeitjie Afroedura leoloensis Sekhukhuneland Flat Gecko Sekhukhuneland Platgeitjie Afroedura loveridgei Loveridge's Flat Gecko Loveridge se Platgeitjie Afroedura major Swazi Flat Gecko Swazi Platgeitjie Afroedura maripi Mariepskop Flat Gecko Mariepskop Platgeitjie Afroedura marleyi Marley's Flat Gecko Marley se Platgeitjie Afroedura multiporis Woodbush Flat Gecko Woodbush Platgeijtie Afroedura namaquensis Namaqua Flat Gecko Namakwa Platgeitjie Afroedura nivaria Drakensberg Flat Gecko Drakensberg Platgeitjie Afroedura pienaari Pienaar’s Flat Gecko Pienaar se Platgeitjie Afroedura pondolia Pondo Flat Gecko Pondo Platgeitjie Afroedura pongola Pongola Flat Gecko Pongola Platgeitjie Afroedura rupestris Abel Erasmus Flat Gecko Abel Erasmus platgeitjie Afroedura rondavelica Blyde River