Scincella Lateralis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List Common Name Scientific Name Status Snakes Cape cobra Naja nivea Puffadder Bitis arietans Albany adder Bitis albanica very rare Night adder Causes rhombeatus Bergadder Bitis atropos Horned adder Bitis cornuta Boomslang Dispholidus typus Rinkhals Hemachatus hemachatus Herald/Red-lipped snake Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Olive house snake Lamprophis inornatus Night snake Lamprophis aurora Brown house snake Lamprophis fuliginosus fuliginosus Speckled house snake Homoroselaps lacteus Wolf snake Lycophidion capense Spotted harlequin snake Philothamnus semivariegatus Speckled bush snake Bitis atropos Green water snake Philothamnus hoplogaster Natal green watersnake Philothamnus natalensis occidentalis Shovel-nosed snake Prosymna sundevalli Mole snake Pseudapsis cana Slugeater Duberria lutrix lutrix Common eggeater Dasypeltis scabra scabra Dappled sandsnake Psammophis notosticus Crossmarked sandsnake Psammophis crucifer Black-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus laevissimus Common/Red-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus rufulus Tortoises/terrapins Angulate tortoise Chersina angulata Leopard tortoise Geochelone pardalis Green parrot-beaked tortoise Homopus areolatus Marsh/Helmeted terrapin Pelomedusa subrufa Tent tortoise Psammobates tentorius Lizards/geckoes/skinks Rock Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus niloticus niloticus Water Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus exanthematicus albigularis Tasman's Girdled Lizard Cordylus tasmani Cape Girdled Lizard Cordylus cordylus Southern Rock Agama Agama atra Burrowing -

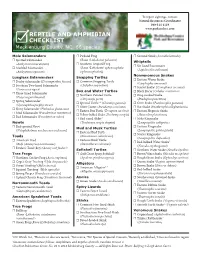

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Reptile Rap Newsletter of the South Asian Reptile Network ISSN 2230-7079 No.15 | January 2013 Date of Publication: 22 January 2013 1

Reptile Rap Newsletter of the South Asian Reptile Network No.15 | January 2013 ISSN 2230-7079 Date of publication: 22 January 2013 1. Crocodile, 1. 2. Crocodile, Caiman, 3. Gharial, 4.Common Chameleon, 5. Chameleon, 9. Chameleon, Flap-necked 8. Chameleon Flying 7. Gecko, Dragon, Ptychozoon Chamaeleo sp. Fischer’s 10 dilepsis, 6. &11. Jackson’s Frill-necked 21. Stump-tailed Skink, 20. Gila Monster, Lizard, Green Iguana, 19. European Iguana, 18. Rhinoceros Antillean Basilisk, Iguana, 17. Lesser 16. Green 15. Common Lizard, 14. Horned Devil, Thorny 13. 12. Uromastyx, Lizard, 34. Eastern Tortoise, 33. 32. Rattlesnake Indian Star cerastes, 22. 31. Boa,Cerastes 23. Python, 25. 24. 30. viper, Ahaetulla Grass Rhinoceros nasuta Snake, 29. 26. 27. Asp, Indian Naja Snake, 28. Cobra, haje, Grater African 46. Ceratophrys, Bombina,45. 44. Toad, 43. Bullfrog, 42. Frog, Common 41. Turtle, Sea Loggerhead 40. Trionychidae, 39. mata Mata 38. Turtle, Snake-necked Argentine 37. Emydidae, 36. Tortoise, Galapagos 35. Turtle, Box 48. Marbled Newt Newt, Crested 47. Great Salamander, Fire Reptiles, illustration by Adolphe Millot. Source: Nouveau Larousse Illustré, edited by Claude Augé, published in Paris by Librarie Larousse 1897-1904, this illustration from vol. 7 p. 263 7 p. vol. from 1897-1904, this illustration Larousse Librarie by published in Paris Augé, Claude by edited Illustré, Larousse Nouveau Source: Millot. Adolphe by illustration Reptiles, www.zoosprint.org/Newsletters/ReptileRap.htm OPEN ACCESS | FREE DOWNLOAD REPTILE RAP #15, January 2013 Contents A new record of the Cochin Forest Cane Turtle Vijayachelys silvatica (Henderson, 1912) from Shendurney Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala, India Arun Kanagavel, 3–6pp New Record of Elliot’s Shieldtail (Gray, 1858) in Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve, Eastern Ghats, Andhra Pradesh, India M. -

Project Name

PROPOSED LAGUNA BAY RESORT AND VISITORS CENTRE JEFFREYS BAY, EASTERN CAPE SPECIALIST REPORT - ECOLOGICAL Prepared for: Berkowitz & Associates 100 William Road Norwood 2192 Prepared by: Coastal & Environmental Services GRAHAMSTOWN P.O. Box 934 Grahamstown, 6140 046 622 2364 Also in East London www.cesnet.co.za DECEMBER 2010 This Report should be sited as follows: Coastal & Environmental Services, December 2010: Laguna Bay Resort and Visitors Centre, Jeffrey’s Bay, Eastern Cape, Ecological Assessment, CES, Grahamstown. COPYRIGHT INFORMATION This document contains intellectual property and propriety information that is protected by copyright in favour of Coastal & Environmental Services and the specialist consultants. The document may therefore not be reproduced, used or distributed to any third party without the prior written consent of Coastal & Environmental Services. This document is prepared exclusively for submission to Berkowitz & Associates, and is subject to all confidentiality, copyright and trade secrets, rules intellectual property law and practices of South Africa. Specialist Ecological Report – December 2010 THE PROJECT TEAM Prof Roy Lubke, Botanical Specialist, been involved in the study and research of coastal dune systems in South Africa, specialising in the rehabilitation of dune systems. These studies include availability of plant pathogens and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza in dune systems and on dune plants; plant succession and dynamics of dune systems; the effects of potentially invasive species on dune systems and the restoration of dune systems. Professor Lubke has held CSIR and FRD national programme funded projects in South Africa, and has managed European Union-funded projects on marram grass and the use of indigenous species for dune rehabilitation, in association with colleagues from the Netherlands, the United Kingom and Botswana. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Sexual Size Dimorphism and Feeding Ecology of Eutropis Multifasciata (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) in the Central Highlands of Vietnam

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 9(2):322−333. Submitted: 8 March 2014; Accepted: 2 May 2014; Published: 12 October 2014. SEXUAL SIZE DIMORPHISM AND FEEDING ECOLOGY OF EUTROPIS MULTIFASCIATA (REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SCINCIDAE) IN THE CENTRAL HIGHLANDS OF VIETNAM 1, 5 2 3 4 CHUNG D. NGO , BINH V. NGO , PHONG B. TRUONG , AND LOI D. DUONG 1Faculty of Biology, College of Education, Hue University, Hue, Thua Thien Hue 47000, Vietnam, 2Department of Life Sciences, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Tainan 70101, Taiwan, e-mail: [email protected] 3Faculty of Natural Sciences and Technology, Tay Nguyen University, Buon Ma Thuot, Dak Lak 55000, Vietnam 4College of Education, Hue University, Hue, Thua Thien Hue 47000, Vietnam 5Corresponding author, e-mail:[email protected] Abstract.—Little is known about many aspects of the ecology of the Common Sun Skink, Eutropis multifasciata (Kuhl, 1820), a terrestrial viviparous lizard found in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. We measured males and females to determine whether this species exhibits sexual size dimorphism and whether there was a correlation between feeding ecology and body size. We also examined spatiotemporal and sexual variations in dietary composition and prey diversity index. We used these data to examine whether the foraging pattern of these skinks corresponded to the pattern of a sit-and-wait predator or a widely foraging predator. The average snout-vent length (SVL) was significantly larger in adult males than in adult females. When SVL was taken into account as a covariate, head length and width and mouth width were larger in adult males than in adult females. -

Common Species

Common Species on District Lands The Southwest Florida Water Management District (District) manages water resources in the west- central portion of Florida according to legislative mandates. The District uses public land acquisition funds to protect key lands for water resources. The natural communities, plants and animals on these lands also benefi t from a level of protection that can be experienced and enjoyed through recreational opportunities made available on District lands. Every year, approximately 2.5 million people visit the more than 436,000 acres of public conservation lands acquired by the District and its partners. The lands are open to the public for activities such as hiking, bicycling, hunting, horseback riding, fi shing, camping, picnicking and studying nature. The District provides these recreational opportunities so that residents may experience healthy natural communities. An array of natural landscapes is available from the meandering Outstanding Florida Southwest Florida Water Management District Waters riverine systems, the cypress domes and strands, swamps and hammocks, to the scrub, sandhill, and pine fl atwoods. The Common Species on District Lands brochure provides insight to what you may experience while recreating on public lands managed by the District. CONSERVATION LANDS Southwest Florida Water Management District Mammals Southwest Florida Water Management District iStock W Barbour - Smithsonian Institute Roger Virginia Brazilian Opossum Free-Tailed Bat Didelphis virginiana Tadarida brasiliensis iStock Ivy -

Check List 17 (1): 27–38

17 1 ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES Check List 17 (1): 27–38 https://doi.org/10.15560/17.1.27 A herpetological survey of Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary Dillon Jones1, Bethany Foshee2, Lee Fitzgerald1 1 Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections, Department of Ecology and Conservation Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. 2 Houston Audubon, 440 Wilchester Blvd. Houston, TX 77079 USA. Corresponding author: Dillon Jones, [email protected] Abstract Urban herpetology deals with the interaction of amphibians and reptiles with each other and their environment in an ur- ban setting. As such, well-preserved natural areas within urban environments can be important tools for conservation. Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary is an 18-acre wooded sanctuary located west of downtown Houston, Texas and is the headquarters to Houston Audubon Society. This study compared iNaturalist data with results from visual encounter surveys and aquatic funnel traps. Results from these two sources showed 24 species belonging to 12 families and 17 genera of herpetofauna inhabit the property. However, several species common in surrounding areas were absent. Combination of data from community science and traditional survey methods allowed us to better highlight herpe- tofauna present in the park besides also identifying species that may be of management concern for Edith L. Moore. Keywords Community science, iNaturalist, urban herpetology Academic editor: Luisa Diele-Viegas | Received 27 August 2020 | Accepted 16 November 2020 | Published 6 January 2021 Citation: Jones D, Foshee B, Fitzgerald L (2021) A herpetology survey of Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary. Check List 17 (1): 27–28. https://doi. -

Lizard ID Guide

Lizards of Anderson County, TN Lizards are extraordinary gifts of nature. World-wide there are close to 6,000 species. The United States is home to more than100 native species, along with many exotic species that have become established, especially in Florida. Tennessee has 9 species, 6 of which are listed for Anderson County. Some are fairly widespread and easy to observe, such as the Common Five-lined Skink below. Unfortunately, the liberal use of pesticides, combined with predation by free roaming house cats have taken a heavy toll on our lizard populations. Most lizards are insect eating machines and their ecological services should be promoted through backyard and schoolyard wildlife habitat projects. Lizard watching is great fun, and over time, observers can gain interesting insights into lizard behavior. Your backyard may be a good place to start your lizarding career. This guide will be helpful for identifying our local lizards and will also provide you with examples of lizard behaviors to observe. Some species must be captured—this can be challenging—to insure accurate identification. Please see the back page for more resources. Lizarding Lizard watching, often referred to as lizarding, will likely never be as popular as bird watching (birding), but there is an advantage to being a “lizarder.” Unlike birders, you don’t need to be an early riser. Bright sunny days with warm temperatures are the keys for successful lizarding, but like birding, close-up binoculars are helpful. A lizard’s life centers around three performance activities: 1) avoiding predators, 2) feeding, and 3) reproduction. Lizard performance is all about optimal body temperature. -

Early German Herpetological Observations and Explorations in Southern Africa, with Special Reference to the Zoological Museum of Berlin

Bonner zoologische Beiträge Band 52 (2003) Heft 3/4 Seiten 193–214 Bonn, November 2004 Early German Herpetological Observations and Explorations in Southern Africa, With Special Reference to the Zoological Museum of Berlin Aaron M. BAUER Department of Biology, Villanova University, Villanova, Pennsylvania, USA Abstract. The earliest herpetological records made by Germans in southern Africa were casual observations of common species around Cape Town made by employees of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) during the mid- to late Seven- teenth Century. Most of these records were merely brief descriptions or lists of common names, but detailed illustrations of many reptiles were executed by two German illustrators in the employ of the VOC, Heinrich CLAUDIUS and Johannes SCHUMACHER. CLAUDIUS, who accompanied Simon VAN DER STEL to Namaqualand in 1685, left an especially impor- tant body of herpetological illustrations which are here listed and identified to species. One of the last Germans to work for the Dutch in South Africa was Martin Hinrich Carl LICHTENSTEIN who served as a physician and tutor to the last Dutch governor of the Cape from 1802 to 1806. Although he did not collect any herpetological specimens himself, LICHTENSTEIN, who became the director of the Zoological Museum in Berlin in 1813, influenced many subsequent workers to undertake employment and/or expeditions in southern Africa. Among the early collectors were Karl BERGIUS and Ludwig KREBS. Both collected material that is still extant in the Berlin collection today, including a small number of reptile types. Because of LICHTENSTEIN’S emphasis on specimens as items for sale to other museums rather than as subjects for study, many species first collected by KREBS were only described much later on the basis of material ob- tained by other, mostly British, collectors. -

First Record of Brown Forest Skink, Scincella Cherriei (Cope, 1893) (Squamata:Scincidae) in El Salvador

Herpetology Notes, volume 13: 715-716 (2020) (published online on 25 August 2020) First record of brown forest skink, Scincella cherriei (Cope, 1893) (Squamata:Scincidae) in El Salvador Antonio E. Valdenegro-Brito1,2, Néstor Herrera-Serrano3, and Uri O. García-Vázquez1,* The Scincella Mittleman, 1950 genus is composed by 2015; Valdenegro-Brito et al., 2016; McCranie, 2018). 36 species, 26 restricted to eastern Asia and 10 species Here, we report the first record of S. cherrie from El are known in the New World in North America, and Salvador. The digital photographs of specimens were Mesoamerica (Myers and Donelly, 1991; Nguyen et al., submitted to the Colección digital de vertebrados de 2019). For El Salvador in Central America, Scincella la Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza, UNAM assata (Cope, 1864) represents the only species of (MZFZ-IMG). the genus know for the country (Köhler et al., 2006). While conducting fieldwork in El Salvador, on 10 Scincella cherriei (Cope, 1893) is characterised November 2019, we observed two male juvenile by possessing 30 to 36 rows of scales around the individuals (MZFZ-IMG254-56 and MZFZ-IMG257- midbody, 58-72 dorsal scales, thick and moderately 260; Fig. 1) of S. cherriei in a coffee plantation within long pentadactyl limbs, average snout-vent length of an oak pine forest in the locality of San José Sacare, 55 mm; the dorsal colouration is dark brown with a municipality of La Palma, Chalatenango department mottled pattern throughout the body, and a well-defined (14. 27079ºN, 89. 17995ºW; datum WGS84) 1215 lateral dark stripe only in the head and neck, which m a.s.l.