Check List 17 (1): 27–38

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Yellow-Bellied Water Snake Plain-Bellied Water

Nature Flashcards Snakes All photos are subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Public License Based on Nature Quiz Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 United States unless copyright otherwise By Phil Huxford noted. TMN-COT Meeting November, 2013 Texas Master Naturalist Cradle of Texas Chapter Cradle of Texas Chapter Yellow-bellied Water Snake Plain-bellied Water Snake Nerodia erythrogaster flavigaster Elliptical eye pupils Bright yellow underneath Found around ponds, lakes, swamps, and wet bottomland forests 2 – 3 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Broad-banded Water snake Nerodia fasciata confluens Dark, wide bands separated by yellow Bold, dark checked stripes Strong swimmer Cradle of Texas Chapter 2 – 4 feet long Blotched Water Snake Nerodia erythrogaster transversa Black-edged; dark brown dorsal markings Yellow or sometimes orange belly Lives in small ponds, ditches, and rain-filled pools Typically 2 – 5 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Diamond-back Water Snake Northern Diamond-back Water Snake Nerodia rhombifer Heavy-bodied, large girth Can be dark brown Head somewhat flattened and wide Texas’ largest Nerodia Strikes without warning and viciously 4 – 6’ long Cradle of Texas Chapter Photo by J.D. Wilson http://srelherp.uga.edu/snakes/ Western Mud Snake Mud Snake Farancia abacura Lives in our area but rarely seen Glossy black above Red belly with black lines in belly Found in wooded swampland and wet areas Does not bite when handled but pokes tail like stinger 3 – 4 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Texas Coral Snake Micrurus fulvius tenere Blunt head; shiny, slender body Round pupils Colors red, yellow, black Lives in partly wooded organic material Cradle of Texas Chapter Usually 2 – 3 feet long Record: 47 ¾ inches in Brazoria County ‘Red touches yellow – kill a fellow. -

Amphibians Present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve

Amphibians present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. The species list was generated from data compiled from NPS observations and during a 2001-2002 reptile and amphibian inventory conducted by Noah J. Anderson and Dr. Richard A. Seigel, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, Louisiana. Common Name Scientific Name Habitat Association Smallmouth salamander Ambystoma texanum hardwood forests Three-toed amphiuma Amphiuma tridactylum swamp, marsh, restricted to aquatic habitats in hardwood forests Dwarf salamander Eurycea quadridigitata hardwood forests, marsh Eastern newt Notophthalmus viridescens found in and near aquatic habitats Southern dusky salamander Desmognathus auriculatus hardwood forests Lesser siren Siren intermedia swamp, marsh Northern cricket frog Acris crepitans all habitats Gulf coast toad Bufo valliceps all habitats Greenhouse frog Eleutherodactylus planirostris hardwood forests Eastern narrowmouth toad Gastrophryne carolinensis all habitats Bird-voiced treefrog Hyla avivoca hardwood forests, swamp Green treefrog Hyla cinerea all habitats Squirrel treefrog Hyla squirella swamp, hardwood forests Spring peeper Pseudacris crucifer swamp, hardwood forests Chorus frog Pseudacris triseriata hardwood forests, swamp Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana hardwood forests, swamp Bronze frog Rana clamitans all habitats Pig frog Rana grylio marsh Southern leopard frog Rana sphenocephala swamp, marsh Reptiles present in the Barataria Preserve of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. -

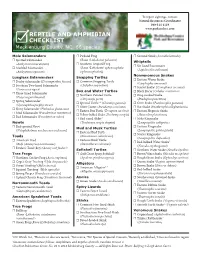

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

Missouri's Toads and Frogs Booklet

TOADSMissouri’s andFROGS by Jeffrey T. Briggler and Tom R. Johnson, Herpetologists www.MissouriConservation.org © 1982, 2008 Missouri Conservation Commission Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Missouri Department of Conservation is available to all individuals without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability. Questions should be directed to the Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 180, Jefferson City, MO 65102, (573) 751-4115 (voice) or 800-735-2966 (TTY), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Federal Assistance, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop: MBSP-4020, Arlington, VA 22203. Cover photo: Eastern gray treefrog by Tom R. Johnson issouri toads and frogs are colorful, harmless, vocal and valuable. Our forests, prairies, rivers, swamps and marshes are Mhome to a multitude of toads and frogs, but few people know how many varieties we have, how to tell them apart, or much about their natural history. Studying these animals and sharing their stories with fellow Missourians is one of the most pleasurable and rewarding aspects of our work. Toads and frogs are amphibians—a class Like most of vertebrate animals that also includes amphibians, salamanders and the tropical caecilians, which are long, slender, wormlike and legless. frogs and Missouri has 26 species and subspecies (or toads have geographic races) of toads and frogs. Toads and frogs differ from salamanders by having an aquatic relatively short bodies and lacking tails at adulthood. Being an amphibian means that tadpole stage they live two lives: an aquatic larval or tadpole and a semi- stage and a semi-aquatic or terrestrial adult stage. -

By a Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasypus Novemcinctus) in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica

Edentata: in press Electronic version: ISSN 1852-9208 Print version: ISSN 1413-4411 http://www.xenarthrans.org FIELD NOTE Predation of a Central American coral snake (Micrurus nigrocinctus) by a nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica Eduardo CarrilloA and Todd K. FullerB,1 A Instituto Internacional en Conservación y Manejo de Vida Silvestre, Universidad Nacional, Apdo. 1350, Heredia, Costa Rica. E-mail: [email protected] B Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts 01003, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Corresponding author Abstract We describe the manner in which a nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) killed a Cen- tral American coral snake (Micrurus nigrocinctus) that it subsequently ate. The armadillo repeatedly ran towards, jumped, flipped over in mid-air, and landed on top of the snake with its back until the snake was dead. Keywords: armadillo, behavior, food, predation, snake Depredación de una serpiente de coral de América Central (Micrurus nigrocinctus) por un armadillo de nueve bandas (Dasypus novemcinctus) en el Parque Nacional Santa Rosa, Costa Rica Resumen En esta nota describimos la manera en que un armadillo de nueve bandas (Dasypus novemcinc- tus) mató a una serpiente de coral de América Central (Micrurus nigrocinctus) que posteriormente comió. El armadillo corrió varias veces hacia adelante, saltó, se dio vuelta en el aire y aterrizó sobre la serpiente con la espalda hasta que la serpiente estuvo muerta. Palabras clave: armadillo, comida, comportamiento, depredación, serpiente Nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinc- The ~4-kg nine-banded armadillo is distributed tus) feed mostly on arthropods such as beetles, ter- from the southeast and central United States to Uru- mites, and ants, but also consume bird eggs and guay and northern Argentina, Granada, Trinidad “unusual items” such as fruits, fungi, and small verte- and Tobago, and the Margarita Islands (Loughry brates (McBee & Baker, 1982; Wetzel, 1991; Carrillo et al., 2014). -

Common Species

Common Species on District Lands The Southwest Florida Water Management District (District) manages water resources in the west- central portion of Florida according to legislative mandates. The District uses public land acquisition funds to protect key lands for water resources. The natural communities, plants and animals on these lands also benefi t from a level of protection that can be experienced and enjoyed through recreational opportunities made available on District lands. Every year, approximately 2.5 million people visit the more than 436,000 acres of public conservation lands acquired by the District and its partners. The lands are open to the public for activities such as hiking, bicycling, hunting, horseback riding, fi shing, camping, picnicking and studying nature. The District provides these recreational opportunities so that residents may experience healthy natural communities. An array of natural landscapes is available from the meandering Outstanding Florida Southwest Florida Water Management District Waters riverine systems, the cypress domes and strands, swamps and hammocks, to the scrub, sandhill, and pine fl atwoods. The Common Species on District Lands brochure provides insight to what you may experience while recreating on public lands managed by the District. CONSERVATION LANDS Southwest Florida Water Management District Mammals Southwest Florida Water Management District iStock W Barbour - Smithsonian Institute Roger Virginia Brazilian Opossum Free-Tailed Bat Didelphis virginiana Tadarida brasiliensis iStock Ivy -

Triadica Sebifera), on Development and Survival of Anuran Larvae Author(S): Taylor B

Effects of an Invasive Plant, Chinese Tallow (Triadica sebifera), on Development and Survival of Anuran Larvae Author(s): Taylor B. Cotten, Matthew A. Kwiatkowski, Daniel Saenz, and Michael Collyer Source: Journal of Herpetology, 46(2):186-193. Published By: The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles https://doi.org/10.1670/10-311 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1670/10-311 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 46, No. 2, 186–193, 2012 Copyright 2012 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Effects of an Invasive Plant, Chinese Tallow (Triadica sebifera), on Development and Survival of Anuran Larvae 1,2 1,3 4 1 TAYLOR B. COTTEN, MATTHEW A. KWIATKOWSKI, DANIEL SAENZ, AND MICHAEL COLLYER 1Department of Biology, Stephen F. Austin State University, PO Box 13003, Nacogdoches, Texas 75962, USA 4Southern Research Station, U.S. -

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana Non-venomous Snakes (25 Species) For more info: Buttermilk Racer Coluber constrictor anthicus 318-773-9393 Eastern Coachwhip Coluber flagellum flagellum www.learnaboutcritters.org Prairie Kingsnake Lampropeltis calligaster [email protected] Speckled Kingsnake Lampropeltis holbrooki www.facebook.com/learnaboutcritters Western Milksnake Lampropeltis gentilis Northern Rough Greensnake Opheodrys aestivus aestivus Alligator (1 species) Western Ratsnake Pantherophis obsoletus American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis Slowinski’s Cornsnake † Pantherophis slowinskii Flat-headed Snake † Tantilla gracilis Western Wormsnake † Carphophis vermis Lizards (10 Species) Mississippi Ring-necked Snake Diadophis punctatus stictogenys Western Mudsnake Farancia abacura reinwardtii Northern Green Anole Anolis carolinensis Eastern Hog-nosed Snake Heterodon platirhinos Prairie Lizard Sceloporus consobrinus Mississippi Green Watersnake Nerodia cyclopion Southern Coal Skink † Plestiodon anthracinus pluvialis Plain-bellied Watersnake Nerodia erythrogaster Common Five-lined Skink Plestiodon fasciatus Broad-banded Watersnake Nerodia fasciata confluens Broad-headed Skink Plestiodon laticeps Graham's Crayfish Snake Regina grahamii Southern Prairie Skink † Plestiodon septentrionalis obtusirostris Gulf Swampsnake Liodytes rigida sinicola Little Brown Skink Scincella lateralis Dekay’s Brownsnake Storeria dekayi Eastern Six-lined Racerunner Aspidoscelis sexlineata sexlineata Red-bellied Snake -

The Southern Watersnake (Nerodia Fasciata) in Folsom, California: History, Population Attributes, and Relation to Other Introduced Watersnakes in North America

THE SOUTHERN WATERSNAKE (NERODIA FASCIATA) IN FOLSOM, CALIFORNIA: HISTORY, POPULATION ATTRIBUTES, AND RELATION TO OTHER INTRODUCED WATERSNAKES IN NORTH AMERICA FINAL REPORT TO: U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office 2800 Cottage Way, Room W-2605 Sacramento, California 95825-1846 UNDER COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT #11420-1933-CM02 BY: ECORP Consulting, Incorporated 2260 Douglas Blvd., Suite 160 Roseville, California 95661 Eric W. Stitt, M. S., University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources, Tucson Peter S. Balfour, M. S., ECORP Consulting Inc., Roseville, California Tara Luckau, University of Arizona, Dept. of Ecology and Evolution, Tucson Taylor E. Edwards, M. S., University of Arizona, Genomic Analysis and Technology Core The Southern Watersnake (Nerodia fasciata) in Folsom, California: History, Population Attributes, and Relation to Other Introduced Watersnakes in North America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 The Southern Watersnake (Nerodia fasciata)................................................................3 Study Area ....................................................................................................................6 METHODS ..........................................................................................................................9 Surveys and Hand Capture.............................................................................................9 Trapping.......................................................................................................................11 -

Northern Population Segment of the Copperbelly Water Snake (Nerodia Erythrogaster Neglecta) Recovery Plan

U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northern Population Segment of the Copperbelly Water Snake (Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta) Recovery Plan December 2008 Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region Fort Snelling, MN Cover graphic The drawing of Nerodia erythrogaster is reproduced with permission of the authors from the book, North American Watersnakes: A Natural History, by J. Whitfield Gibbons and Michael E. Dorcas, published by the University of Oklahoma Press (2004). Drawing by Peri Mason, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory. DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or conserve listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the Service. They represent the official position of the Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. LITERATURE CITATION SHOULD READ AS FOLLOWS: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Northern Population Segment of the Copperbelly Water Snake (Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta) Recovery Plan. Fort Snelling, Minnesota. ix + 79 pp. ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PLAN CAN BE OBTAINED FROM: U.S. -

Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION 597 Herpetological Review, 2015, 46(4), 597–601. © 2015 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA Distributional maps found in Amphibians and Reptiles of records for a variety of amphibian and reptile species in Georgia. Georgia (Jensen et al. 2008), along with subsequent geographical All records below were verified by David Bechler (VSU), Nikole distribution notes published in Herpetological Review, serve Castleberry (GMNH), David Laurencio (AUM), Lance McBrayer as essential references for county-level occurrence data for (GSU), and David Steen (SRSU), and datum used was WGS84. herpetofauna in Georgia. Collectively, these resources aid Standard English names follow Crother (2012). biologists by helping to identify distributional gaps for which to target survey efforts. Herein we report newly documented county CAUDATA — SALAMANDERS DIRK J. STEVENSON AMBYSTOMA OPACUM (Marbled Salamander). CALHOUN CO.: CHRISTOPHER L. JENKINS 7.8 km W Leary (31.488749°N, 84.595917°W). 18 October 2014. D. KEVIN M. STOHLGREN Stevenson. GMNH 50875. LOWNDES CO.: Langdale Park, Valdosta The Orianne Society, 100 Phoenix Road, Athens, (30.878524°N, 83.317114°W). 3 April 1998. J. Evans. VSU C0015. Georgia 30605, USA First Georgia record for the Suwannee River drainage. MURRAY JOHN B. JENSEN* CO.: Conasauga Natural Area (34.845116°N, 84.848180°W). 12 Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 116 Rum November 2013. N. Klaus and C. Muise. GMNH 50548. Creek Drive, Forsyth, Georgia 31029, USA DAVID L. BECHLER Department of Biology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, AMBYSTOMA TALPOIDEUM (Mole Salamander). BERRIEN CO.: Georgia 31602, USA St.