Activity Patterns and Habitat Selection in a Population of the African Fire Skink (Lygosoma Fernandi) from the Niger Delta, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution of Lygosoma Guentheri (Peter, 1879) (Reptilia: Scincidae)

JoTT NOTE 2(4): 837-840 Distribution of Lygosoma guentheri is the most speciose containing over (Peter, 1879) (Reptilia: Scincidae) in 600 species in 45 genera (Griffith et al. 2000). The genus Lygosoma Andhra Pradesh, India Gray, 1828 includes forms that are 1 2 terrestrial and semi-fossorial and S.M. Maqsood Javed , M. Seetharamaraju , K. Thulsi Rao 3, Farida Tampal 4 & C. Srinivasulu 5 belong to Mabuya group. In India, the genus Lygosoma Gray, 1828 includes nine species, of which Günther’s 1, 4 World Wide Fund for Nature-India (WWF), APSO, 818, Supple Skink Lygosoma guentheri (Peter, 1879) was Castle Hills, Road No. 2, Near NMDC, Vijayanagar Colony, reported only from the Western Ghats from Gujarat to Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh 500057, India 2, 5 Kerala (Smith 1935; Daniel 1962). Rao et al. (2005) Wildlife Biology Section, Department of Zoology, University College of Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad, Andhra reported its presence in the Eastern Ghats based on a Pradesh 500057, India specimen collected in the central Nallamalai Hills, Andhra 3 Eco-Research and Monitoring Laboratories, Nagarjunasagar Pradesh. Recently, Srinivasulu & Das (2008) recognized Srisailam Tiger Reserve, Sundipenta, Kurnool District, Andhra its presence in the Nallamalai Hills. This paper provides Pradesh 518102, India Email: [email protected] information on the distribution, habits and habitat of L. guentheri in Andhra Pradesh One adult specimen (106mm) of L. guentheri was Family Scincidae is the largest among lizards, captured, examined and released by SMMJ from the comprising more than 1300 species (Bauer 1998). Of the Bhimaram (18050’N & 79042’E), Adilabad District on 15 five subfamilies recognized, the subfamily Lygosominae June 2007, around 1300hr. -

Notes and Comments on the Distribution of Two Endemic Lygosoma Skinks (Squamata: Scincidae: Lygosominae) from India

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 December 2014 | 6(14): 6726–6732 Note The family Scincidae is the Notes and comments on the distribution largest group among lizards, of two endemic Lygosoma skinks comprising more than 1558 species (Squamata: Scincidae: Lygosominae) ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) (Uetz & Hosek 2014). Of the from India ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) seven subfamilies recognized, the subfamily Lygosominae contains Raju Vyas OPEN ACCESS over 52 species in five genera (Uetz & Hosek 2014). The genus 505, Krishnadeep Tower, Mission Road, Fatehgunj, Vadodara, Gujarat Lygosoma Hardwicke & Gray, 1827 has a long and 390002, India [email protected] complicated nomenclatural history (see Geissler et al. 2011). In India, the genus Lygosoma is represented by nine species, of which five are endemic (Datta-Roy et al. 2014), including Günther’s Supple Skink Lygosoma City, Vadodara District and after examination both the guentheri (Peters, 1879) and the Lined Supple Skink skinks were released in the nearby riverine habitat of Lygosoma lineata (Gray, 1839). These are less studied, Vishwamitri River within the limits of the city area. terrestrial, insectivorous and diurnal supple-skinks Lygosoma guentheri: On 12 December 2013, a large (Molur & Walker 1998). Both these species are found adult specimen of Lygosoma (Image 1) was captured by in peninsular India and are classified ‘Least Concern’ a local rescue group from a garden in Vadodara City, species by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Gujarat. The specimen was identified as L. guentheri (Srinivasulu & Srinivasulu 2013a, b). with the help of the literature (Boulenger 1890; Smith Reserved forest and degraded areas of the northern 1935). -

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, Volume 60, Number 1, Pp

Integrative and Comparative Biology Integrative and Comparative Biology, volume 60, number 1, pp. 190–201 doi:10.1093/icb/icaa015 Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology SYMPOSIUM Convergent Evolution of Elongate Forms in Craniates and of Locomotion in Elongate Squamate Reptiles Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icb/article-abstract/60/1/190/5813730 by Clark University user on 24 July 2020 Philip J. Bergmann ,* Sara D. W. Mann,* Gen Morinaga,1,*,† Elyse S. Freitas‡ and Cameron D. Siler‡ *Department of Biology, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA; †Department of Integrative Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA; ‡Department of Biology and Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA From the symposium “Long Limbless Locomotors: The Mechanics and Biology of Elongate, Limbless Vertebrate Locomotion” presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology January 3–7, 2020 at Austin, Texas. 1E-mail: [email protected] Synopsis Elongate, snake- or eel-like, body forms have evolved convergently many times in most major lineages of vertebrates. Despite studies of various clades with elongate species, we still lack an understanding of their evolutionary dynamics and distribution on the vertebrate tree of life. We also do not know whether this convergence in body form coincides with convergence at other biological levels. Here, we present the first craniate-wide analysis of how many times elongate body forms have evolved, as well as rates of its evolution and reversion to a non-elongate form. We then focus on five convergently elongate squamate species and test if they converged in vertebral number and shape, as well as their locomotor performance and kinematics. -

The Herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and Lower Cuando River Catchments of South-Eastern Angola

Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 10(2) [Special Section]: 6–36 (e126). The herpetofauna of the Cubango, Cuito, and lower Cuando river catchments of south-eastern Angola 1,2,*Werner Conradie, 2Roger Bills, and 1,3William R. Branch 1Port Elizabeth Museum (Bayworld), P.O. Box 13147, Humewood 6013, SOUTH AFRICA 2South African Institute for Aquatic Bio- diversity, P/Bag 1015, Grahamstown 6140, SOUTH AFRICA 3Research Associate, Department of Zoology, P O Box 77000, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth 6031, SOUTH AFRICA Abstract.—Angola’s herpetofauna has been neglected for many years, but recent surveys have revealed unknown diversity and a consequent increase in the number of species recorded for the country. Most historical Angola surveys focused on the north-eastern and south-western parts of the country, with the south-east, now comprising the Kuando-Kubango Province, neglected. To address this gap a series of rapid biodiversity surveys of the upper Cubango-Okavango basin were conducted from 2012‒2015. This report presents the results of these surveys, together with a herpetological checklist of current and historical records for the Angolan drainage of the Cubango, Cuito, and Cuando Rivers. In summary 111 species are known from the region, comprising 38 snakes, 32 lizards, five chelonians, a single crocodile and 34 amphibians. The Cubango is the most western catchment and has the greatest herpetofaunal diversity (54 species). This is a reflection of both its easier access, and thus greatest number of historical records, and also the greater habitat and topographical diversity associated with the rocky headwaters. -

Reptile Rap Newsletter of the South Asian Reptile Network ISSN 2230-7079 No.15 | January 2013 Date of Publication: 22 January 2013 1

Reptile Rap Newsletter of the South Asian Reptile Network No.15 | January 2013 ISSN 2230-7079 Date of publication: 22 January 2013 1. Crocodile, 1. 2. Crocodile, Caiman, 3. Gharial, 4.Common Chameleon, 5. Chameleon, 9. Chameleon, Flap-necked 8. Chameleon Flying 7. Gecko, Dragon, Ptychozoon Chamaeleo sp. Fischer’s 10 dilepsis, 6. &11. Jackson’s Frill-necked 21. Stump-tailed Skink, 20. Gila Monster, Lizard, Green Iguana, 19. European Iguana, 18. Rhinoceros Antillean Basilisk, Iguana, 17. Lesser 16. Green 15. Common Lizard, 14. Horned Devil, Thorny 13. 12. Uromastyx, Lizard, 34. Eastern Tortoise, 33. 32. Rattlesnake Indian Star cerastes, 22. 31. Boa,Cerastes 23. Python, 25. 24. 30. viper, Ahaetulla Grass Rhinoceros nasuta Snake, 29. 26. 27. Asp, Indian Naja Snake, 28. Cobra, haje, Grater African 46. Ceratophrys, Bombina,45. 44. Toad, 43. Bullfrog, 42. Frog, Common 41. Turtle, Sea Loggerhead 40. Trionychidae, 39. mata Mata 38. Turtle, Snake-necked Argentine 37. Emydidae, 36. Tortoise, Galapagos 35. Turtle, Box 48. Marbled Newt Newt, Crested 47. Great Salamander, Fire Reptiles, illustration by Adolphe Millot. Source: Nouveau Larousse Illustré, edited by Claude Augé, published in Paris by Librarie Larousse 1897-1904, this illustration from vol. 7 p. 263 7 p. vol. from 1897-1904, this illustration Larousse Librarie by published in Paris Augé, Claude by edited Illustré, Larousse Nouveau Source: Millot. Adolphe by illustration Reptiles, www.zoosprint.org/Newsletters/ReptileRap.htm OPEN ACCESS | FREE DOWNLOAD REPTILE RAP #15, January 2013 Contents A new record of the Cochin Forest Cane Turtle Vijayachelys silvatica (Henderson, 1912) from Shendurney Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala, India Arun Kanagavel, 3–6pp New Record of Elliot’s Shieldtail (Gray, 1858) in Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve, Eastern Ghats, Andhra Pradesh, India M. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care Sheets Are Often An

MAHS Care Sheet Master List *By Eric Roscoe Care sheets are often an excellent starting point for learning more about the biology and husbandry of a given species, including their housing/enclosure requirements, temperament and handling, diet , and other aspects of care. MAHS itself has created many such care sheets for a wide range of reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates we believe to have straightforward care requirements, and thus make suitable family and beginner’s to intermediate level pets. Some species with much more complex, difficult to meet, or impracticable care requirements than what can be adequately explained in a one page care sheet may be multiple pages. We can also provide additional links, resources, and information on these species we feel are reliable and trustworthy if requested. If you would like to request a copy of a care sheet for any of the species listed below, or have a suggestion for an animal you don’t see on our list, contact us to let us know! Unfortunately, for liability reasons, MAHS is unable to create or publish care sheets for medically significant venomous species. This includes species in the families Crotilidae, Viperidae, and Elapidae, as well as the Helodermatidae (the Gila Monsters and Mexican Beaded Lizards) and some medically significant rear fanged Colubridae. Those that are serious about wishing to learn more about venomous reptile husbandry that cannot be adequately covered in one to three page care sheets should take the time to utilize all available resources by reading books and literature, consulting with, and working with an experienced and knowledgeable mentor in order to learn the ropes hands on. -

Hoser, R. T. 2018. New Australian Lizard Taxa Within the Greater Egernia Gray, 1838 Genus Group Of

Australasian Journal of Herpetology 49 Australasian Journal of Herpetology 36:49-64. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) Published 30 March 2018. ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) New Australian lizard taxa within the greater Egernia Gray, 1838 genus group of lizards and the division of Egernia sensu lato into 13 separate genera. RAYMOND T. HOSER 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: snakeman (at) snakeman.com.au Received 1 Jan 2018, Accepted 13 Jan 2018, Published 30 March 2018. ABSTRACT The Genus Egernia Gray, 1838 has been defined and redefined by many authors since the time of original description. Defined at its most conservative is perhaps that diagnosis in Cogger (1975) and reflected in Cogger et al. (1983), with the reverse (splitters) position being that articulated by Wells and Wellington (1985). They resurrected available genus names and added to the list of available names at both genus and species level. Molecular methods have largely confirmed the taxonomic positions of Wells and Wellington (1985) at all relevant levels and their legally available ICZN nomenclature does as a matter of course follow from this. However petty jealousies and hatred among a group of would-be herpetologists called the Wüster gang (as detailed by Hoser 2015a-f and sources cited therein) have forced most other publishing herpetologists since the 1980’s to not use anything Wells and Wellington. Therefore the most commonly “in use” taxonomy and nomenclature by published authors does not reflect the taxonomic reality. This author will not be unlawfully intimidated by Wolfgang Wüster and his gang of law-breaking thugs using unscientific methods to destabilize zoology as encapsulated in the hate rant of Kaiser et al. -

Abstracts Part 1

375 Poster Session I, Event Center – The Snowbird Center, Friday 26 July 2019 Maria Sabando1, Yannis Papastamatiou1, Guillaume Rieucau2, Darcy Bradley3, Jennifer Caselle3 1Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA, 2Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, Chauvin, LA, USA, 3University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA Reef Shark Behavioral Interactions are Habitat Specific Dominance hierarchies and competitive behaviors have been studied in several species of animals that includes mammals, birds, amphibians, and fish. Competition and distribution model predictions vary based on dominance hierarchies, but most assume differences in dominance are constant across habitats. More recent evidence suggests dominance and competitive advantages may vary based on habitat. We quantified dominance interactions between two species of sharks Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos and Carcharhinus melanopterus, across two different habitats, fore reef and back reef, at a remote Pacific atoll. We used Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) to observe dominance behaviors and quantified the number of aggressive interactions or bites to the BRUVs from either species, both separately and in the presence of one another. Blacktip reef sharks were the most abundant species in either habitat, and there was significant negative correlation between their relative abundance, bites on BRUVs, and the number of grey reef sharks. Although this trend was found in both habitats, the decline in blacktip abundance with grey reef shark presence was far more pronounced in fore reef habitats. We show that the presence of one shark species may limit the feeding opportunities of another, but the extent of this relationship is habitat specific. Future competition models should consider habitat-specific dominance or competitive interactions. -

On Further Specimens of the Poorly-Known Pruthi's Skink Lygosoma Pruthi

Asian Journal of Conservation Biology, December 2018. Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 128-132 AJCB: SC0032 ISSN 2278-7666 ©TCRP 2018 On further specimens of the poorly-known Pruthi’s skink Lygosoma pruthi (Sharma, 1977) with an expanded description S.R. Ganesh1* and R. Aengals2,3 1Chennai Snake Park, Rajbhavan Post, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India 2Zoological Survey of India, Southern Regional Station, Chennai, India 3Zoological Survey of India, Sunderbans Regional Centre, Canning, India (Accepted November 25, 2018) ABSTRACT We report on further specimens of the rare and elusive Pruthi’s skink Lygosoma pruthi based on both pre- served and live specimens. We review and summarise its taxonomic and nomenclatural history. Detailed description of a voucher specimen from Pachaimalai is provided and the species is illustrated in life depict- ing both adult and juvenile morphology, based on live skinks sighted in Teerthamalai. Nuptial colouration of breeding males and life colouration in general are provided herein for the first time. We review its past records and allocate previous partly- or un-allocated sightings to this nominate species based on congruent morphology and distribution. We expand its geographic range and present additional localities such as Pa- chaimalai, Bilgiri, Melagiri, Jawadi, Gingee, Shevaroys, Kolli and Sirumalai, apart from its type locality – Chitteri. Key words: Eastern Ghats, morphology, scalation, skink, Pachaimalai, Teerthamalai INTRODUCTION (Gray, 1839), L. vosmaerii (Gray, 1839), L. albopuncta- tum (Gray, 1846), L. guentheri (Peters, 1879) have been The Pruthi’s skink Lygosoma pruthi (Sharma, 1977) is a studied (Ganesh et al., 2017; Javed et al., 2010; Seetha- little known species of skink in India (Sharma, 1977, ramaraju et al., 2009; Vyas et al., 2009) such aspects of 2004; Venugopal 2010). -

Captive Wildlife Exclusion List

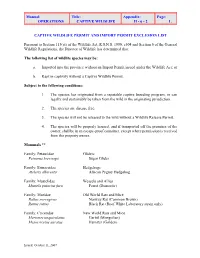

Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 1. CAPTIVE WILDLIFE PERMIT AND IMPORT PERMIT EXCLUSION LIST Pursuant to Section 113(at) of the Wildlife Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c504 and Section 6 of the General Wildlife Regulations, the Director of Wildlife has determined that: The following list of wildlife species may be: a. Imported into the province without an Import Permit issued under the Wildlife Act; or b. Kept in captivity without a Captive Wildlife Permit. Subject to the following conditions: 1. The species has originated from a reputable captive breeding program, or can legally and sustainably be taken from the wild in the originating jurisdiction. 2. The species are disease free. 3. The species will not be released to the wild without a Wildlife Release Permit. 4. The species will be properly housed, and if transported off the premises of the owner, shall be in an escape-proof container, except where permission is received from the property owner. Mammals ** Family: Petauridae Gliders Petuarus breviceps Sugar Glider Family: Erinaceidae Hedgehogs Atelerix albiventis African Pygmy Hedgehog Family: Mustelidae Weasels and Allies Mustela putorius furo Ferret (Domestic) Family: Muridae Old World Rats and Mice Rattus norvegicus Norway Rat (Common Brown) Rattus rattus Black Rat (Roof White Laboratory strain only) Family: Cricetidae New World Rats and Mice Meriones unquiculatus Gerbil (Mongolian) Mesocricetus auratus Hamster (Golden) Issued: October 11, 2007 Manual: Title: Appendix: Page: OPERATIONS CAPTIVE WILDLIFE II - 6 - 2 2. Family: Caviidae Guinea Pigs and Allies Cavia porcellus Guinea Pig Family: Chinchillidae Chinchillas Chincilla laniger Chinchilla Family: Leporidae Hares and Rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus European Rabbit (domestic strain only) Birds Family: Psittacidae Parrots Psittaciformes spp.* All parrots, parakeets, lories, lorikeets, cockatoos and macaws. -

Morphology, Taxonomy and Life Cycles of Some Saurian

MORPHOLOGY, TAXONOMY AND LIFE CYCLES OF SOME SAURIAN HAEMATOZOA by Keith Robert Wallbanks B.Sc. (Lond.) A.R.C.S. 1982 A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London Department of Pure and Applied Biology Imperial College Silwood Park Ascot Berkshire ii TO MY MOTHER AND FATHER WITH GRATITUDE AND LOVE iii Abstract The trypanosomes and Leishmania parasites of lizards are reviewed. The development of Trypanosoma platydactyli in two sandfly species, Sergentomyia minuta and Phlehotomus papatasi and in in vitro culture was followed. In sandflies the blood trypomastigotes passed through amastigote, epimastigote and promastigote phases in the midgut of the fly before developing into short, slender, non-dividing trypomastigotes in the mid- and hind-gut. These short trypomastigotes are presumed to be the infective metatrypomastigotes. In axenic culture T. platydactyli passed through amastigote and epimastigote phases into a promastigote phase. The promastigote phase was very stable and attempts to stimulate -the differentiation of promastigotes to epi- or trypo-mastigotes, by changing culture media, pH values and temperature failed. The trypanosome origin of the promastigotes was proved by the growth of promastigotes in cultures from a cloned blood trypomastigote. The resultant promastigote cultures were identical in general morphology, ultrastructure and the electrophoretic mobility of 8 enzymes to those previously considered to be Leishmania tarentolae. T. platydactyli and L. tarentolae are synonymised and the present status of saurian Leishmania parasites is discussed. Promastigote cultures of T. platydactyli formed intracellular amastigotes. in mouse macrophages, lizard monocytes and lizard kidney cells in vitro. The parasites were rapidly destroyed by mouse macrophages jlii vivo and in vitro at 37°C.