Reconstructing the World of Roman Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantastic W Ays to Travel and Save Money with Go North East Travelling with Uscouldn't Be Simpler! Ten Services Betw Een

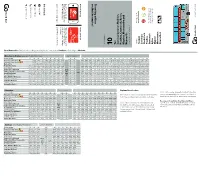

money with Go North East money and save travel to ways Fantastic couldn’t be simpler! couldn’t with us Travelling gonortheast.co.uk the Go North East app. mobile with your to straight times and tickets Live Go North app East Get in touch gonortheast.co.uk 420 5050 0191 @gonortheast simplyGNE 5 mins 5 mins gonortheast.co.uk /gneapp Buses run up to Buses run up to 30 minutes every ramp access find You’ll bus and travel on every on board. advice safety gonortheast.co.uk smartcard. deals on exclusive with everyone, easier for cheaper and travel Makes smartcard the key /thekey the key the key Serving: Hexham Corbridge Stocksfield Prudhoe Crawcrook Ryton Blaydon Metrocentre Newcastle Go North East 10 Bus times from 21 May 2017 21 May Bus times from Ten Ten Hexham, between Services Ryton, Crawcrook, Prudhoe, and Metrocentre Blaydon, Newcastle 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Crawcrook » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Every 30 minutes at Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10X 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle Eldon Square - 0623 0645 0715 0745 0815 0855 0925 0955 25 55 1355 1425 1455 1527 1559 1635 1707 1724 1740 1810 1840 1900 1934 1958 2100 2200 2300 Newcastle Central Station - 0628 0651 0721 0751 0821 0901 0931 1001 31 01 1401 1431 1501 1533 1606 1642 1714 1731 1747 1817 1846 1906 1940 2003 2105 2205 2305 Metrocentre - 0638 0703 0733 0803 0833 0913 0944 1014 44 14 1414 1444 1514 1546 1619 1655 1727 X 1800 1829 1858 1919 1952 2016 2118 2218 2318 Blaydon -

Map for Day out One Hadrian's Wall Classic

Welcome to Hadian’s Wall Country a UNESCO Arriva & Stagecoach KEY Map for Day Out One World Heritage Site. Truly immerse yourself in Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east A Runs Daily the history and heritage of the area by exploring 685 Hadrian’s Wall Classic Tickets and Passes National Trail (See overleaf) by bus and on foot. Plus, spending just one day Arriva Cuddy’s Crags Newcastle - Corbridge - Hexham www.arrivabus.co.uk/north-east Alternative - Roman Traveller’s Guide without your car can help to look after this area of X85 Runs Monday - Friday Military Way (Nov-Mar) national heritage. Hotbank Crags 3 AD122 Rover Tickets The Sill Walk In this guide to estbound These tickets offer This traveller’s guide is designed to help you leave Milecastle 37 Housesteads eet W unlimited travel on Parking est End een Hadrian’s Wall uns r the AD122 service. Roman Fort the confines of your car behind and truly “walk G ee T ont Str ough , Hexham Road Approx Refreshments in the footsteps of the Romans”. So, find your , Lion and Lamb journey times Crag Lough independent spirit and let the journey become part ockley don Mill, Bowes Hotel eenhead, Bypass arwick Bridge Eldon SquaLemingtonre Thr Road EndsHeddon, ThHorsler y Ovington Corbridge,Road EndHexham Angel InnHaydon Bridge,Bar W Melkridge,Haltwhistle, The Gr MarketBrampton, Place W Fr Scotby Carlisle Adult Child Concession Family Roman Site Milecastle 38 Country Both 685 and X85 of your adventure. hr Sycamore 685 only 1 Day Ticket £12.50 £6.50 £9.50 £26.00 Haydon t 16 23 27 -

Roman Britain

Roman Britain Hadrian s Wall - History Vallum Hadriani - Historia “ Having completely transformed the soldiers, in royal fashion, he made for Britain, where he set right many things and - the rst to do so - drew a wall along a length of eighty miles to separate barbarians and Romans. (The Augustan History, Hadrian 11.1)” Although we have much epigraphic evidence from the Wall itself, the sole classical literary reference for Hadrian having built the Wall is the passage above, wrien by Aelius Spartianus towards the end of the 3rd century AD. The original concept of a continuous barrier across the Tyne-Solway isthmus, was devised by emperor Hadrian during his visit to Britain in 122AD. His visit had been prompted by the threat of renewed unrest with the Brigantes tribe of northern Britain, and the need was seen to separate this war-like race from the lowland tribes of Scotland, with whom they had allied against Rome during recent troubles. Components of The Wall Hadrian s Wall was a composite military barrier which, in its nal form, comprised six separate elements; 1. A stone wall fronted by a V-shaped ditch. 2. A number of purpose-built stone garrison forti cations; Forts, Milecastles and Turrets. 3. A large earthwork and ditch, built parallel with and to the south of the Wall, known as the Vallum. 4. A metalled road linking the garrison forts, the Roman Military Way . 5. A number of outpost forts built to the north of the Wall and linked to it by road. 6. A series of forts and lookout towers along the Cumbrian coast, the Western Sea Defences . -

La Libellule

LA LIBELLULE FENROTHER | MORPETH | NORTHUMBERLAND A superb barn conversion with high quality interior situated in a rural yet accessible location LA LIBELLULE FENROTHER | MORPETH | NORTHUMBERLAND APPROXIMATE MILEAGES Morpeth 6.0 miles | Alnwick 15.1 miles | Newcastle International Airport 20.3 miles Newcastle City Centre 21.0 miles ACCOMMODATION IN BRIEF Entrance Hall | Sitting Room | Kitchen/Breakfast Room | Utility Room | Cloakroom Master Bedroom with En-suite Shower Room | Two Further Bedrooms | Family Bathroom Gardens | Parking Finest Properties | Crossways | Market Place | Corbridge | Northumberland | NE45 5AW T: 01434 622234 E: [email protected] finest properties.co.uk THE PROPERTY La Libellule is a delightful stone built barn conversion nestled within a select development with two other properties which was completed in 2008. The property offers a wealth of charm throughout, sympathetically blending the original character with a more modern day feel. The front door enters into a naturally bright entrance hall with flagstone floor, stairs to the first floor and access to the ground floor accommodation. The sitting room sits to one side, offering generous proportions and dual aspect to the north and west. A wood burning stove with stone mantle surround by Chesneys provides a focal point to the room with exposed beams and oak flooring adding to the character. The kitchen/breakfast room provides a good range of bespoke, painted wooden units with contrasting wooden and granite work surfaces as well as Fired Earth tiles to the floor and walls. Integral appliances include a dishwasher, Belfast sink and Rangemaster cooker, whilst a useful utility room accessed off the kitchen has further storage, sink and plumbing for a washing machine. -

Trains Tyne Valley Line

From 15th May to 2nd October 2016 Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Northern Mondays to Fridays Gc¶ Hp Mb Mb Mb Mb Gc¶ Mb Sunderland dep … … 0730 0755 0830 … 0930 … … 1030 1130 … 1230 … 1330 Newcastle dep 0625 0646 0753 0824 0854 0924 0954 1024 1054 1122 1154 1222 1254 1323 1354 Dunston 0758 0859 Metrocentre 0634 0654 0802 0832 0903 0932 1002 1033 1102 1132 1202 1232 1302 1333 1402 Blaydon 0639 | 0806 | 1006 | | 1206 | | 1406 Wylam 0645 0812 0840 0911 1012 1110 1212 1310 1412 Prudhoe 0649 0704 0817 0844 0915 0942 1017 1043 1114 1142 1217 1242 1314 1344 1417 Stocksfield 0654 | 0821 0849 0920 | 1021 | 1119 | 1221 | 1319 | 1421 Riding Mill 0658 | 0826 | 0924 | 1026 | 1123 | 1226 | 1323 | 1426 Corbridge 0702 0830 0928 1030 1127 1230 1327 1430 Hexham arr 0710 0717 0838 0858 0937 0955 1038 1055 1137 1155 1238 1255 1337 1356 1438 Hexham dep … 0717 … 0858 … 0955 … 1055 … 1155 … 1255 … 1357 … Haydon Bridge … 0726 … 0907 … | … 1104 … | … 1304 … | … Bardon Mill … 0733 … 0914 … … 1111 … … 1311 … … Haltwhistle … 0740 … 0921 … 1014 … 1118 … 1214 … 1318 … 1416 … Brampton … 0755 … 0936 … | … 1133 … | … 1333 … | … Wetheral … 0804 … 0946 … … 1142 … … 1342 … … Carlisle arr … 0815 … 0957 … 1046 … 1157 … 1247 … 1354 … 1448 … Mb Mb Wv Mb Gc¶ Mb Ct Mb Sunderland dep … 1430 … 1531 … 1630 … … 1730 … 1843 1929 2039 2211 Newcastle dep 1424 1454 1524 1554 1622 1654 1716 1724 1754 1824 1925 2016 2118 2235 Dunston 1829 Metrocentre 1432 1502 1532 1602 1632 1702 1724 1732 1802 1833 1934 2024 2126 2243 Blaydon | | 1606 -

The Antonine Wall, the Roman Frontier in Scotland, Was the Most and Northerly Frontier of the Roman Empire for a Generation from AD 142

Breeze The Antonine Wall, the Roman frontier in Scotland, was the most and northerly frontier of the Roman Empire for a generation from AD 142. Hanson It is a World Heritage Site and Scotland’s largest ancient monument. The Antonine Wall Today, it cuts across the densely populated central belt between Forth (eds) and Clyde. In The Antonine Wall: Papers in Honour of Professor Lawrence Keppie, Papers in honour of nearly 40 archaeologists, historians and heritage managers present their researches on the Antonine Wall in recognition of the work Professor Lawrence Keppie of Lawrence Keppie, formerly Professor of Roman History and Wall Antonine The Archaeology at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow University, who spent edited by much of his academic career recording and studying the Wall. The 32 papers cover a wide variety of aspects, embracing the environmental and prehistoric background to the Wall, its structure, planning and David J. Breeze and William S. Hanson construction, military deployment on its line, associated artefacts and inscriptions, the logistics of its supply, as well as new insights into the study of its history. Due attention is paid to the people of the Wall, not just the ofcers and soldiers, but their womenfolk and children. Important aspects of the book are new developments in the recording, interpretation and presentation of the Antonine Wall to today’s visitors. Considerable use is also made of modern scientifc techniques, from pollen, soil and spectrographic analysis to geophysical survey and airborne laser scanning. In short, the papers embody present- day cutting edge research on, and summarise the most up-to-date understanding of, Rome’s shortest-lived frontier. -

The Roman Baths Complex Is a Site of Historical Interest in the English City of Bath, Somerset

Aquae Sulis The Roman Baths complex is a site of historical interest in the English city of Bath, Somerset. It is a well-preserved Roman site once used for public bathing. Caerwent Caerwent is a village founded by the Romans as the market town of Venta Silurum. The modern village is built around the Roman ruins, which are some of the best-preserved in Europe. Londinium Londinium was a settlement established on the current site of the City of London around 43 AD. Its bridge over the River Thames turned the city into a road nexus and major port, serving as a major commercial centre in Roman Britain until its abandonment during the 5th century. Dere Street Dere Street or Deere Street is what is left of a Roman road which ran north from Eboracum (York), and continued beyond into what is now Scotland. Parts of its route are still followed by modern roads that we can drive today. St. Albans St. Albans was the first major town on the old Roman road of Watling Street. It is a historic market town and became the Roman city of Verulamium. St. Albans takes its name from the first British saint, Albanus, who died standing up for his beliefs. Jupiter Romans believed Jupiter was the god of the sky and thunder. He was king of the gods in Ancient Roman religion and mythology. Jupiter was the most important god in Roman religion throughout the Empire until Christianity became the main religion. Juno Romans believed Juno was the protector of the Empire. She was an ancient Roman goddess who was queen of all the gods. -

Antonine Wall - Castlecary Fort

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC170 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90009) Taken into State care: 1961 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2005 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ANTONINE WALL - CASTLECARY FORT We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ANTONINE WALL – CASTLECARY FORT BRIEF DESCRIPTION The property is part of the Antonine Wall and contains the remains of a Roman fort and annexe with a stretch of Antonine Wall to the north-east of the fort. The Edinburgh-Glasgow railway cuts across the south section of the fort while modern buildings disturb the north-east corner of the fort and ditch. The Antonine Wall is a linear Roman frontier system of wall and ditch accompanied at stages by forts and fortlets, linked by a road system, stretching for 60km from Bo’ness on the Forth to Old Kilpatrick on the Clyde. It is one of only three linear barriers along the 2000km European frontier of the Roman Empire. These systems are unique to Britain and Germany. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview Archaeological finds indicate the site was used during the Flavian period (AD 79- 87/88). Antonine Wall construction initiated by Emperor Antoninus Pius (AD 138-161) after a successful campaign in AD 139/142 by the Governor of Britain, Lollius Urbicus. -

A Roman Altar from Westerwood on the Antonine Wall by R

A Roman Altar from Westerwood on the Antonine Wall by R. P. Wright The altar here illustrated (PI. 23a) was found3 in ploughing in the spring of 1963 perhaps within r moro , e likel fore f Westerwoowesth e o ty , th jus of to t tAntonine th n do e Walle Th . precise spot could not be determined, but as the altar was unofficial it is more likely to have lain outsiddragges fortboundare e wa aree th th t I ef .fieldth e o d a o t th f ,y o wherrecognise s wa t ei d two days later by Master James Walker and was transferred to Dollar Park Museum. The altar4 is of buff sandstone, 10 in. wide by 25 in. high by 9£ in. thick, and has a rosette with recessed centr focus e plac n stonei e th severas f Th eo .e ha l plough-score bace d th kan n so right side, and was slightly chipped when being hauled off the field, fortunately without any dam- age to the inscription. Much of the lettering was at first obscured by a dark and apparently ferrous concretion, but after some weeks of slow drying this could be brushed off, leaving a slight reddish staininscriptioe Th . n reads: SILVANIS [ET] | QUADRVIS CA[E]|LESTIB-SACR | VIBIA PACATA | FL-VERECV[ND]I | D LEG-VI-VIC | CUM SVIS | V-S-L-M Silvanis Quadr(i)viset Caelestib(us) sacr(wri) Vibia Pacata Fl(avi) Verecundi (uxor) c(enturionis) leg(ionis) VI Vic(tricis) cum suis v(ptum) s(olvii) l(ibens) m(erito) 'Sacred to the Silvanae Quadriviae Caelestes: Vibia Pacata, wife of Flavius Verecundus, centurion Sixte oth f h Legion Victrix, wit r familhhe y willingl deservedld yan y fulfille r vow.he d ' Dedications expressed to Silvanus in the singular are fairly common in Britain,5 as in other provinces. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th.