A Comparative Study of Fonn and Theology in the Works of Flannery O'connor and Simone Weil by Catherine Ann Maxwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This

Theologica Xaveriana ISSN: 0120-3649 ISSN: 2011-219X [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia Poggi, Alfredo Ignacio A Southern Gothic Theology: Flannery O’Connor and Her Religious Conception of the Novel∗ Theologica Xaveriana, vol. 70, 2020, pp. 1-23 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx70.sgtfoc Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=191062490018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative doi: https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx70.sgtfoc A Southern Gothic Theology: Una teología gótica sureña: Flannery O’Connor y su concepción religiosa de la Flannery O’Connor and novela Her Religious Conception Resumen: Mary Flannery O’Connor, a ∗ menudo considerada una de las mejores of the Novel escritoras norteamericanas del siglo XX, parece haber respaldado la existencia de la a “novela católica” como género particular. Alfredo Ignacio Poggi Este artículo muestra las características University of North Georgia descritas por O’Connor sobre este género, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9663-3504 puntualizando la constitución indefinida y problemática de dicha delimitación. Independientemente de la imposibilidad RECIBIDO: 30-07-19. APROBADO: 18-02-20 de definir el término, este artículo sostiene además que la explicación de O’Connor sobre el género trasciende el campo lite- rario y muestra una visión distintiva de Abstract: Mary Flannery O’Connor, often consi- la fe cristiana y una teología sofisticada dered one of the greatest North American writers of que denomino “gótico sureño”. -

Hypnotherapy.Pdf

Hypnotherapy An Exploratory Casebook by Milton H. Erickson and Ernest L. Rossi With a Foreword by Sidney Rosen IRVINGTON PUBLISHERS, Inc., New York Halsted Press Division of JOHN WILEY Sons, Inc. New York London Toronto Sydney The following copyrighted material is reprinted by permission: Erickson, M. H. Concerning the nature and character of post-hypnotic behavior. Journal of General Psychology, 1941, 24, 95-133 (with E. M. Erickson). Copyright © 1941. Erickson, M. H. Hypnotic psychotherapy. Medical Clinics of North America, New York Number, 1948, 571-584. Copyright © 1948. Erickson, M. H. Naturalistic techniques of hypnosis. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1958, 1, 3-8. Copyright © 1958. Erickson, M. H. Further clinical techniques of hypnosis: utilization techniques. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1959, 2, 3-21. Copyright © 1959. Erickson, M. H. An introduction to the study and application of hypnosis for pain control. In J. Lassner (Ed.), Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine: Proceedings of the International Congress for Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine. Springer Verlag, 1967. Reprinted in English and French in the Journal of the College of General Practice of Canada, 1967, and in French in Cahiers d' Anesthesiologie, 1966, 14, 189-202. Copyright © 1966, 1967. Copyright © 1979 by Ernest L. Rossi, PhD All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission from the publisher. For information, write to Irvington Publishers, Inc., 551 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10017. Distributed by HALSTED PRESS A division of JOHN WILEY SONS, Inc., New York Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Erickson, Milton H. -

Flannery O'connor

ANALYSIS “The Artificial Nigger” (1955) Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) “I suppose ‘The Artificial Nigger’ is my favorite…. And there is nothing that screams out the tragedy of the South like what my uncle calls ‘nigger statuary.’ And then there’s Peter’s denial. They all got together in that one. You are right about this negativity being in large degree personal. My disposition is a combination of Nelson’s and Hulga’s. Or perhaps I only flatter myself.” O’Connor, Letter (6 September 1955) “Well, I never had heard the phrase before, but my mother was out trying to buy a cow, and she rode up the country a-piece. She had the address of a man who was supposed to have a cow for sale, but she couldn’t find it, so she stopped in a small town and asked the countryman on the side of the road where the house was, and he said, ‘Well, you go into this town and you can’t miss it ‘cause it’s the only house in town with a artificial nigger in front of it.’ So I decided I would have to find a story to fit that.” O’Connor, Symposium, Vanderbilt U (1957) “’The Artificial Nigger’ is my favorite and probably the best thing I’ll ever write.” O’Connor, Letter (10 March 1957) “We begin here with nothing more uncommon than a rustic old man taking his rustic grandson for his first trip to the city. While their backwoodness is a bit grotesque and the old man’s vanity provides touching humor, metaphysical drama doesn’t overturn secular seeming until the man publicly denies his relationship to the boy to escape retribution and to give the humor a new dimension. -

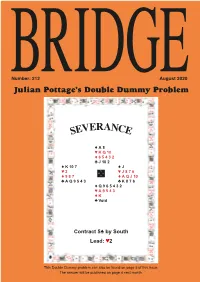

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

BA Thesis O'connor

UNIVERZITA KARLOVA V PRAZE – FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV ANGLOFONNÍCH LITERATUR A KULTUR The Conflict of Country and City in Flannery O’Connor’s Short Stories BAKALÁ ŘSKÁ PRÁCE Vedoucí bakalá řské práce (supervisor): doc. Clare Wallace, PhD, M.A. Zpracoval (author): Anna Hejzlarová Studijní obor (subject): Anglistika a amerikanistika Praha, 14.1.2013 i Declaration Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalá řskou práci vypracoval/a samostatně, že jsem řádn ě citoval/a všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného či stejného titulu. I declare that the following BA thesis is my own work for which I used only the sources and literature mentioned, and that this thesis has not been used in the course of other university studies or in order to acquire the same or another type of diploma. V Praze dne 14.1.2013 Anna Hejzlarová ii Permission Souhlasím se zap ůjčením bakalá řské práce ke studijním ú čel ům. I have no objections to the BA thesis being borrowed and used for study purposes. iii Acknowledgements Tímto bych ráda pod ěkovala doc. Clare Wallace, PhD, M.A., za cenné rady, trp ělivost a vedení, jež mi pomohly p ři psaní a formování této práce. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to doc. Clare Wallace, PhD, M.A., for her valuable advice, patience, and guidance, which helped me to write and shape this thesis. iv Table of Contents Declaration .................................................................................................................................ii -

Flannery O'connor's Images of the Self

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 1978 CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF MICHAEL JOHN LEE Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation LEE, MICHAEL JOHN, "CLOWNS AND CAPTIVES: FLANNERY O'CONNOR'S IMAGES OF THE SELF" (1978). Doctoral Dissertations. 1210. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1210 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document ' ave been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “ target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Region, Idolatry, and Catholic Irony: Flannery O'connor's Modest Literary Vision

01-logos-jackson-pp13-40 2/8/02 3:51 PM Page 13 Robert Jackson Region, Idolatry, and Catholic Irony: Flannery O’Connor’s Modest Literary Vision Introduction:On Adolescence and Authority,Region,and Religion Writing to his lifelong friend Walker Percy in 1969, the Mis- sissippi novelist and historian Shelby Foote assessed the life and career of their contemporary and fellow Southerner Flannery O’Connor: She had the real clew, the solid gen, on what it’s about; I just wish she’d had time to demonstrate it fully instead of in frag- ments. She’s a minor-minor writer,not because she lacked the talent to be a major one, but simply because she died before her development had time to evolve out of the friction of just living enough years to soak up the basic joys and sorrows. That, and I think because she also didn’t have time to turn her back on Christ, which is something every great Catholic writer (that I know of, I mean) has done. Joyce, Proust—and, I think, Dostoevsky, who was just about the least Christian man I ever encountered except maybe Hemingway....I always had the feeling that O’Connor was going to be one of our big talents; I didn’t know she was dying—which of course logos 5:1 winter 2002 01-logos-jackson-pp13-40 2/8/02 3:51 PM Page 14 logos means I misunderstood her. She was a slow developer, like most good writers, and just plain didn’t have the time she needed to get around to the ordinary world, which would have been her true subject after she emerged from the “grotesque” one she explored throughout the little time she had.1 Foote’s image of O’Connor is striking not only for what it express- es about her life and writings, but perhaps even more so for its imaginative portrait of the person who might have evolved into a very different writer with age and maturity. -

Glossary of Bridge Terms

GLOSSARY OF BRIDGE TERMS Alert When your partner makes a conventional bid you must alert this to the opponents by knocking the table (or displaying the ‘Alert’ card if using bidding boxes). Auction Another term for the bidding. Avoidance An attempt to prevent a particular defender from regaining the lead. Balanced A hand containing no void, no singleton and not more than one Hand doubleton. Barrier When planning your opener's rebid, imagine a ‘barrier’ just above your first suit at the next level up. A new suit rebid below the barrier shows 12-15 points (occasionally 16 or 17 points after a 1 level response when opener doesn’t have enough for a jump shift). A new suit rebid above the barrier that isn’t a jump shift shows 16-19 points (also known as a reverse). Blocked A suit is blocked if there is a high card in the short hand that prevents the suit from being cashed. A player will often aim to unblock the suit. Break The way in which the defenders’ cards in a particular suit are divided between their two hands. For example, a 4-2 break indicates that with 6 cards in a suit missing, one defender has 4 cards of the suit and his partner has 2 cards. Also referred to as split. Cash Playing a card that is certain to win the trick. This card is known as a master. Clear a suit Knocking out the opponents’ last stopper in a suit, after which it will be possible to cash one’s tricks in the suit. -

Following the Equator by Mark Twain</H1>

Following the Equator by Mark Twain Following the Equator by Mark Twain This etext was produced by David Widger FOLLOWING THE EQUATOR A JOURNEY AROUND THE WORLD BY MARK TWAIN SAMUEL L. CLEMENS HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT THE AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MDCCCXCVIII COPYRIGHT 1897 BY OLIVIA L. CLEMENS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FORTIETH THOUSAND THIS BOOK page 1 / 720 Is affectionately inscribed to MY YOUNG FRIEND HARRY ROGERS WITH RECOGNITION OF WHAT HE IS, AND APPREHENSION OF WHAT HE MAY BECOME UNLESS HE FORM HIMSELF A LITTLE MORE CLOSELY UPON THE MODEL OF THE AUTHOR. THE PUDD'NHEAD MAXIMS. THESE WISDOMS ARE FOR THE LURING OF YOUTH TOWARD HIGH MORAL ALTITUDES. THE AUTHOR DID NOT GATHER THEM FROM PRACTICE, BUT FROM OBSERVATION. TO BE GOOD IS NOBLE; BUT TO SHOW OTHERS HOW TO BE GOOD IS NOBLER AND NO TROUBLE. CONTENTS CHAPTER I. The Party--Across America to Vancouver--On Board the Warrimo--Steamer Chairs-The Captain-Going Home under a Cloud--A Gritty Purser--The Brightest Passenger--Remedy for Bad Habits--The Doctor and the Lumbago --A Moral Pauper--Limited Smoking--Remittance-men. page 2 / 720 CHAPTER II. Change of Costume--Fish, Snake, and Boomerang Stories--Tests of Memory --A Brahmin Expert--General Grant's Memory--A Delicately Improper Tale CHAPTER III. Honolulu--Reminiscences of the Sandwich Islands--King Liholiho and His Royal Equipment--The Tabu--The Population of the Island--A Kanaka Diver --Cholera at Honolulu--Honolulu; Past and Present--The Leper Colony CHAPTER IV. Leaving Honolulu--Flying-fish--Approaching the Equator--Why the Ship Went Slow--The Front Yard of the Ship--Crossing the Equator--Horse Billiards or Shovel Board--The Waterbury Watch--Washing Decks--Ship Painters--The Great Meridian--The Loss of a Day--A Babe without a Birthday CHAPTER V. -

FLANNERY O'connor's PICTORIAL TEXT Ruth Reiniche

Sign Language: Flannery O'Connor's Pictorial Text Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Reiniche, Ruth Mary Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 22:20:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/325225 1 SIGN LANGUAGE: FLANNERY O’CONNOR’S PICTORIAL TEXT Ruth Reiniche ____________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Ruth Reiniche, titled Sign Language: Flannery O’Connor’s Pictorial Text and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 5/2/2014 Charles W. Scruggs PhD _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 5/2/2014 Edgar Dryden PhD. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 5/2/2014 Judy Temple PhD. Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. ________________________________________________ Date: 5/2/2014 Dissertation Director: Charles W. -

Reading Flannery O'connor in Spain: from Andalusia To

READING FLANNERY O’CONNor IN SPAIN: FroM ANDALUSIA TO ANDALUCÍA Mark Bosco, S. J. & Beatriz Valverde (Eds.) TABLE of CONTENTS Flannery O’Connor: Catholic and Quixotic . 7 Mark Bosco, S.J. and Beatriz Valverde Reaching the World from the South: . .23 the Territory of Flannery O’Connor Guadalupe Arbona Another of Her Disciples: The Literary Grotesque . .49 and its Catholic Manifestations in Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor and La vida invisible by Juan Manuel de Prada Anne-Marie Pouchet “Andalusia on the Liffey”: Sacred Monstrosity in O’Connor and Joyce . 71 Michael Kirwan, S.J. Death’s Personal Call: The Aesthetics of Catholic Eschatology . .89 in Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find” and Muriel Spark’s Memento Mori Anabel Altemir-Giral and Ismael Ibáñez-Rosales Quixotism and Modernism: The Conversion of Hazel Motes. 107 Brent Little 5 Reading Flannery O’Connor in Spain: From Andalusia to Andalucía A Christian Malgré Lui: Crisis, Transition, and the Quixotic Pursuit . 129 of the Ideal in Flannery O’Connor’s Fiction Xiamara Hohman The Other as Angels: O’Connor’s Case for Radical Hospitality. 153 Michael Bruner “A Purifying Terror”: Apocalypse, Apostasy, and Alterity . .171 in Flannery O’Connor’s “The Enduring Chill” José Liste Noya An Unpleasant Little Jolt: Flannery O’Connor’s Creation ex Chaos . 191 Thomas Wetzel 6 FLANNERY O’coNNor: CATHOLIC AND QUIXOTIC MARK Bosco, S.J. BEATRIZ VALVERDE “Flannery O’Connor is unique. There is no one like her. You can’t lump her with Faulkner, you can’t lump her Walker Percy, you can’t lump her with anyone.” So proclaims the American novelist Alice McDermott regarding the place of Flannery O’Connor in the American canon of literature. -

The Displaced Person

BOOKS BY Flannery O'Connor Flannery O'Connor THE NOV E L S Wise Blood COMPLETE The Violent Bear It Away STORIES STORIES A Good Man Is Hard to Find Everything That Rises Must Converge with an introduction by Robert Fitzgerald NON-FICTION Mystery and Manners edited and with an introduction by Robert and SaUy Fitzgerald The Habit of Being edited and with an introduction by Sally Fitzgerald Straus and Giroux New York ~ I Farrar, Straus and Giroux 19 Union Square West, New York 10003 Copyright © 1946, 194il, 195(l, 1957, 1958, 1960, [()61, Hi)2, 1963, 1964,l()65, 1970, 1971 by [he Estate of Mary Flannery O'Connor. © 1949, 1952, [955,1960,1\162 by Contents O'Connor. Introduction copyright © 1971 by Robert Giroux All rights reserved Distributed in Canada by Douglas & McImyre Ltd. Printed in the United States of America First published in J(171 by Farrar, Straus and (;iroux INTRODUCTION by Robert Giroux Vll Quotations from Inters are used by permission of Robert Fitzgerald and of the Estate and are copyright © 197 r by the Estate of Mary Flannery O'Connor. The ten stories The Geranium 3 from A Good ManIs Hard to Find, copyright © [953,1954,1955 by Flannery O'Connor, The Barber 15 arc used by special arrangement with Harcourt Hrace Jovanovich, Inc Wildcat 20 The Crop 33 of Congress catalog card number; 72'171492 The Turkey 42 Paperback ISBN: 0-374-51536-0 The Train 54 The Peeler 63 Designed by Herb Johnson The Heart of the Park ~h A Stroke of Good Fortune 95 Enoch and the Gorilla lOS A Good Man Is Hard to Find II7 55 57 59 61 62 60 58 56 A Late Encounter with the Enemy 134 The Life You Save May Be Your Own 14'5 The River 157 A Circle in the Fire 175 The Displaced Person 194 A Temple of the Holy Ghost The Artificial Nigger 249 Good Country People 27 1 You Can't Be Any Poorer Than Dead 292 Greenleaf 311 A View of the Woods 335 v The Displaced Person / I95 them.