Dynamics of Youth Euroscepticism a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zealous Democrats: Islamism and Democracy in Egypt, Indonesia and Turkey

Lowy Institute Paper 25 zealous democrats ISLAMISM AND DEMOCRACY IN EGYPT, INDONESIA AND TURKEY Anthony Bubalo • Greg Fealy Whit Mason First published for Lowy Institute for International Policy 2008 Anthony Bubalo is program director for West Asia at the Lowy Institute for International Policy. Prior to joining the Institute he worked as an Australian diplomat for 13 PO Box 102 Double Bay New South Wales 1360 Australia years and was a senior Middle East analyst at the Offi ce of www.longmedia.com.au National Assessments. Together with Greg Fealy he is the [email protected] co-author of Lowy Institute Paper 05 Joining the caravan? Tel. (+61 2) 9362 8441 The Middle East, Islamism and Indonesia. Lowy Institute for International Policy © 2008 ABN 40 102 792 174 Dr Greg Fealy is senior lecturer and fellow in Indonesian politics at the College of Asia and the Pacifi c, The All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part Australian National University, Canberra. He has been a of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (including but not limited to electronic, visiting professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School mechanical, photocopying, or recording), without the prior written permission of the of Advanced International Studies, Washington DC, and copyright owner. was also an Indonesia analyst at the Offi ce of National Assessments. He has published extensively on Indonesian Islamic issues, including co-editing Expressing Islam: Cover design by Longueville Media Typeset by Longueville Media in Esprit Book 10/13 Religious life and politics in Indonesia (ISEAS, 2008) and Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia (ISEAS, 2005). -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Rise of the Welfare Party in Perspective

Third World Quarterly ISSN: 0143-6597 (Print) 1360-2241 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctwq20 The political economy of Islamic resurgence in Turkey: The rise of the Welfare Party in perspective Ziya Onis To cite this article: Ziya Onis (1997) The political economy of Islamic resurgence in Turkey: The rise of the Welfare Party in perspective, Third World Quarterly, 18:4, 743-766, DOI: 10.1080/01436599714740 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436599714740 Published online: 25 Aug 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1047 View related articles Citing articles: 61 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ctwq20 Download by: [SOAS, University of London] Date: 06 March 2017, At: 22:18 ThirdW orldQu arterly,V ol18,No4,pp743±766,1997 ThepoliticaleconomyofIslamic resurgence inTurkey:therise ofthe WelfareParty in perspective ZIÇ YA OÈ NISË Therisingelectoralfortu neso ftheWelfareP arty(Refah P artisi( RP)), a party thatd ifferentiatesitselfsh arplyfro mthe`orthodox’p artieso ftherightorlefto f thepoliticalspectrumbycam paigningex plicitlyonanIslam istp latform, constitutesth emosto bviousorv isiblesig nofIslamicresurg encein th eTurkish 1 context. Theturning-pointinth eevolutionof RP intoa majorpoliticalmove- mentcamewiththe m unicipalg overnmentelecti onsofMarch1 994during whichth epartym anagedto cap tureth emayorshipsofthetwokeym etropolitan areaso fIstanbulandA nkara.T hisvicto -

Redalyc.Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: a Case Study On

Argumentum E-ISSN: 2176-9575 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Brasil Sinem ARIKAN, Elif Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: A Case Study on Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Argumentum, vol. 8, núm. 1, enero-abril, 2016, pp. 115-125 Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Vitória, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=475555256018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18315/argumentum.v8i1.11884 ARTIGO Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: A Case Study on Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Prestação de assistência social a nível local: um estudo de caso no Município de Istambul Elif Sinem ARIKAN1 Abstract: In this article I tried to find traces of a neo-conservative model the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipal- ity in Turkey. Firstly I tried to explain significant collaboration between liberalism and conservatism in the neoliberal context. Subsequently, I tried to evaluate the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality to see the neo- conservative administration’s effects on local administrations based on market-oriented administration ra- tionale. I tried to explain that the gender discourse was strengthened because of such administration rationale. I tried to evaluate this matter profoundly. I mentioned the Ladies Commission of RP (Welfare Party) and Kadın Koordinasyon Merkezi (Women Coordination Center (WCC)) in the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality as examples of models of conservative women’s political organizations. Keywords: Neoliberalism. -

Meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network 1-2 October 2020 List of Participants

as of 02/10/2020 Meeting of the OECD Global Parliamentary Network 1-2 October 2020 List of participants MP or Chamber or Political Party Country Parliamentary First Name Last Name Organisation Job Title Biography (MPs only) Official represented Pr. Ammar Moussi was elected as Member of the Algerian Parliament (APN) for the period 2002-2007. Again, in the year Algerian Parliament and Member of Peace Society 2017 he was elected for the second term and he's now a member of the Finance and Budget commission of the National Algeria Moussi Ammar Parliamentary Assembly Member of Parliament Parliament Movement. MSP Assembly. In addition, he's member of the parliamentary assembly of the Mediterranean PAM and member of the executif of the Mediterranean bureau of tha Arab Renewable Energy Commission AREC. Abdelmajid Dennouni is a Member of Parliament of the National People’s Assembly and a Member of finances and Budget Assemblée populaire Committee, and Vice president of parliamentary assembly of the Mediterranean. He was previously a teacher at Oran Member of nationale and Algeria Abdelmajid Dennouni Member of Parliament University, General Manager of a company and Member of the Council of Competitiveness, as well as Head of the Parliament Parliamentary Assembly organisaon of constucng, public works and hydraulics. of the Mediterranean Member of Assemblée Populaire Algeria Amel Deroua Member of Parliament WPL Ambassador for Algeria Parliament Nationale Assemblée Populaire Algeria Parliamentary official Safia Bousnane Administrator nationale Lucila Crexell is a National Senator of Argentina and was elected by the people of the province of Neuquén in 2013 and reelected in 2019. -

Voter Preferences, Electoral Cleavages and Support for Islamic Parties

Voter Preferences, Electoral Cleavages and Support for Islamic Parties Sabri Ciftci Department of Political Science Kansas State University, Manhattan [email protected] Yusuf Tekin Gaziosmanpasa University, Tokat, TURKEY [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the 2009 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 2‐5 2009, Chicago, IL Abstract Increasing scholarly attention has recently been focused upon the origins and fortunes of Islamic parties. This paper examines the individual determinants of support for these parties utilizing the fifth wave of the World Values Survey. It is argued that the distribution of individual preferences along political cleavages like left‐right, secularism‐Islamism, and regime‐opposition are critical explanatory variables. The cases under investigation are Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey and Party of Justice and Development (PJD) in Morocco. The results of the multinomial logit show that Islamic parties obtain support from a broad spectrum of voters and this support base is best understood in relation to the distribution of voter preferences for rival parties. Furthermore, left‐right and Islamism appear to be the most important cleavages in the electoral markets under investigation. 1 Introduction Increasing scholarly attention has recently been focused upon the origins and fortunes of Islamic parties. In this vein, a good amount of research examined the Islamic party moderation (Kalyvas, 2000; Schwedler, 2007) and their commitment to democracy (Tibbi, 2008, p. 43-48; Nasr, 2005). While there is merit in investigating these questions, it is also important to understand the microlevel foundations of support for Islamic parties. Surprisingly, little empirical research has been conducted toward this end (for an exception see Carkoglu, 2006; Tepe, 2007) and studies with a comparative orientation are rare (Garcia-Rivero and Kotze, 2007; Tepe and Baum, 2008). -

TRANSFORMATION of POLITICAL ISLAM in TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’S Pro-EU Turn

PARTY POLITICS VOL 9. No.4 pp. 463–483 Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi www.sagepublications.com TRANSFORMATION OF POLITICAL ISLAM IN TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’s Pro-EU Turn Saban Taniyici ABSTRACT The recent changes in the Islamist party’s ideology and policies in Turkey are analysed in this article. The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) was ousted from power in June 1997 and was outlawed by the Consti- tutional Court (CC) in March 1998. After the ban, the WP elite founded the Virtue Party and changed policies on a number of issues. They emphasized democracy and basic human rights and freedoms in the face of this external shock. The WP’s hostile policy toward the European Union (EU) was changed. This process of change is discussed and it is argued that the EU norms presented a political opportunity structure for the party elites to influence the change of direction of the party. When the VP was banned by the CC in June 2001, the VP elites split and founded two parties which differ on a number of issues but have positive policies toward the EU. KEY WORDS European Union party change political Islam political oppor- tunity structure Turkey Introduction The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) in Turkey recently changed its decades-old policy of hostility toward the European Union (EU) and began strongly to support Turkey’s accession to the Union, thereby raising doubts about the inevitability of a civilizational conflict between Islam and the West. 1 This change was part of the party’s broader image transformation which took place after its leader, Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan,2 was forced by the Turkish political establishment to resign from a coalition government in June 1997. -

Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey

A Freedom House Special Report Democracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkey Susan Corke Andrew Finkel David J. Kramer Carla Anne Robbins Nate Schenkkan Executive Summary 1 Cover: Mustafa Ozer AFP / GettyImages Introduction 3 The Media Sector in Turkey 5 Historical Development 5 The Media in Crisis 8 How a History Magazine Fell Victim 10 to Self-Censorship Media Ownership and Dependency 12 Imprisonment and Detention 14 Prognosis 15 Recommendations 16 Turkey 16 European Union 17 United States 17 About the Authors Susan Corke is Andrew Finkel David J. Kramer Carla Anne Robbins Nate Schenkkan director for Eurasia is a journalist based is president of Freedom is clinical professor is a program officer programs at Freedom in Turkey since 1989, House. Prior to joining of national security at Freedom House, House. Ms. Corke contributing regularly Freedom House in studies at Baruch covering Central spent seven years at to The Daily Telegraph, 2010, he was a Senior College/CUNY’s School Asia and Turkey. the State Department, The Times, The Transatlantic Fellow at of Public Affairs and He previously worked including as Deputy Economist, TIME, the German Marshall an adjunct senior as a journalist Director for European and CNN. He has also Fund of the United States. fellow at the Council in Kazakhstan and Affairs in the Bureau written for Sabah, Mr. Kramer served as on Foreign Relations. Kyrgyzstan and of Democracy, Human Milliyet, and Taraf and Assistant Secretary of She was deputy editorial studied at Ankara Rights, and Labor. appears frequently on State for Democracy, page editor at University as a Critical Turkish television. -

Explaining Turkish Party and Public Support for the EU Seth Jolly

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Archive of European Integration Explaining Turkish Party and Public Support for the EU Seth Jolly, Syracuse University Sibel Oktay, Syracuse University February 2011 Draft Presented at the Biennial Meeting of the European Union Studies Association, Boston, 3-5 March 2011 Abstract: The three main Turkish political parties, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), the Republican People's Party (CHP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), each favor Turkish accession to the European Union, with varying degrees of reservations. Turkish public support for EU membership is also divided, with recent surveys showing only 50% of the population views the EU positively. In this paper, we first evaluate the extent of support for European integration among Turkish mainstream and minor parties using Chapel Hill Expert Survey data and case studies. Next, building from the vast literature on public and party support for the EU in western European states, we develop utilitarian and identity hypotheses to explain public support. Using Eurobarometer data, we test these explanations. In this analysis, we compare Turkish parties and public to their counterparts in eastern and western Europe. I. Introduction What explains the levels of mass and elite support toward European integration in Turkey? To what extent do the established theories of public and elite attitudes toward integration explain the Turkish case? Can we integrate our findings to the comparative scope of the literature, or is Turkish exceptionalism a reality? During the era of permissive consensus, European integration was an elite-driven process. But the recent literature on attitudes toward European integration has established that the era of permissive consensus (Lindberg and Scheingold 1970) is over (Carrubba 2001, Hooghe and Marks 2005, De Vries and Edwards 2009); in other words, Euroskepticism should be studied at the mass level along with the elite level. -

London Wide Assembly Final Results

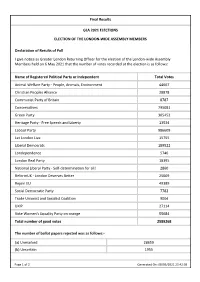

Final Results GLA 2021 ELECTIONS ELECTION OF THE LONDON-WIDE ASSEMBLY MEMBERS Declaration of Results of Poll I give notice as Greater London Returning Officer for the election of the London-wide Assembly Members held on 6 May 2021 that the number of votes recorded at the election is as follows: Name of Registered Political Party or Independent Total Votes Animal Welfare Party - People, Animals, Environment 44667 Christian Peoples Alliance 28878 Communist Party of Britain 8787 Conservatives 795081 Green Party 305452 Heritage Party - Free Speech and Liberty 13534 Labour Party 986609 Let London Live 15755 Liberal Democrats 189522 Londependence 5746 London Real Party 18395 National Liberal Party - Self-determination for all! 2860 ReformUK - London Deserves Better 25009 Rejoin EU 49389 Social Democratic Party 7782 Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition 9004 UKIP 27114 Vote Women's Equality Party on orange 55684 Total number of good votes 2589268 The number of ballot papers rejected was as follows:- (a) Unmarked 28659 (b) Uncertain 1955 Page 1 of 2 Generated On: 08/05/2021 23:42:39 (c) Voting for too many 24212 (d) Writing identifying voter 88 (e) Want of official mark 17 Total 54931 And I do hereby declare the eleven London-wide Assembly Member seats have been allocated and filled as follows Name of Registered Political Party Seat Number or Independent 1 Green Party BERRY Sian 2 Liberal Democrats PIDGEON Caroline Valerie 3 Green Party RUSSELL Caroline 4 Conservatives BAILEY Shaun 5 Conservatives BOFF Andrew 6 Green Party POLANSKI Zack 7 Conservatives -

Full Text (PDF)

PEARSON JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES & HUMANITIES 2020 Doi Number :http://dx.doi.org/10.46872/pj.83 THE ROLE OF N. ERBAKAN AND THE WELFARE PARTY IN THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF TURKEY Dr. Namig Mammadov Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences ORCID: 0000-0003-4356-6111 Özet Bu makale, Necmettin Erbakan'ın ve Refah Partisi'nin modern Türkiye'nin siyasi tarihindeki rolünü incelemekte ve analiz etmektedir. Türkiye'de Milli Görüş Hareketi'nin oluşumunda ve gelişiminde ideoloji, sosyal taban ve ana itici güçler ile faaliyetleri de bu makalenin incelenme kısmıdır. Makale ayrıca hareketin önderi, önde gelen bilim adamı ve araştırmacısı, profesör Necmeddin Erbakan'ın rolü de dahil olmak üzere hareketin oluşumunu ve gelişimini etkileyen tarihsel koşulların yanı sıra siyasi arenaya girme nedenleri ve sonuçları da analiz ediyor. N. Erbakan'ın Türkiye'nin siyasi hayatındaki rolü araştırılarak değerlendirilmeye çalışılmıştır. Refah Partisi'nin ana ideolojisinin faizsiz bir serbest piyasa ekonomisi, üretimin güçlendirilmesi, temel insan haklarının korunduğu adil bir toplumun kurulması vb. olduğu kaydedilmiştir. Refah Partisi (RP), aynı yönü temsil eden Ahmet Tekdal liderliğinde 1983 yılında kuruldu. Siyasi yasakların kaldırılmasının ardından N. Erbakan yeniden parti başkanlığına seçildi. 1990'lar, Milli Görüş hareketinin gelişiminde yeni bir aşamaya geldi ve Refah Partisi'nin itibarı yükselmeye başladı. 1995 seçimlerinde parti oyların yüzde 21'ini kazandı. 1996 yılında N. Erbakan, Tansu Çiller liderliğindeki Doğru Yol Partisi ile koalisyon hükümeti kurdu. Bu hükümet 28 Şubat süreci sonucunda istifa etti ve parti feshedildi. Parti üyeleri Fazilet Partisi'ni kurdu. Anahtar kelimeler: Türkiye, N. Erbakan, Milli Görüş Hareketi, Milli Nizam Partisi, Refah Partisi Abstract This article examines and analyzes the role of Najmeddin Erbakan and the Welfare Party in the political history of modern Turkey. -

Political Islam in Turkey

Political Islam in Turkey CEPS Working Document No. 265/April 2007 Senem Aydin and Ruşen Çakır Abstract Turkey differs from the Arab states studied in the CEPS–FRIDE Political Islam project in not only in having a European Union membership prospect, but also in the fact that a broadly Islamist-oriented party has been in office since 2002. The Justice and Development Party (AKP) still enjoys the primary support of pro-Islamic constituencies in Turkish society and its orientation towards the EU has not changed since its assumption of power. An overwhelming majority in the party still sees the EU as the primary anchor of Turkish democracy and modernisation despite the inferred limitations of cooperation on issues relating to the reform of Turkish secularism. Yet the growing mistrust towards the EU as a result of perceived discrimination and EU double standards is beginning to cloud positive views within the party. Decreasing levels of support for EU membership in Turkish society and the fact that explicitly Euro-sceptic positions are now coming from both the left and the right of the political spectrum suggest that the sustainability of the pro-European discourse within the party could be difficult to maintain in the longer run. The present working paper is based on contributions made to a conference on “Political Islam and the European Union” organised by CEPS and La Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior (FRIDE) and hosted by the Fundación Tres Culturas in Sevilla on 24-25 November 2006. At this conference, Arab and Turkish scholars presented papers on the ‘Muslim democrat’ political parties of the Arab Mediterranean states and Turkey.