From Ruler to Pariah: the Life and Times of the True Path Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Left Info Flyer

United for a left alternative in Europe United for a left alternative in Europe ”We refer to the values and traditions of socialism, com- munism and the labor move- ment, of feminism, the fem- inist movement and gender equality, of the environmental movement and sustainable development, of peace and international solidarity, of hu- man rights, humanism and an- tifascism, of progressive and liberal thinking, both national- ly and internationally”. Manifesto of the Party of the European Left, 2004 ABOUT THE PARTY OF THE EUROPEAN LEFT (EL) EXECUTIVE BOARD The Executive Board was elected at the 4th Congress of the Party of the European Left, which took place from 13 to 15 December 2013 in Madrid. The Executive Board consists of the President and the Vice-Presidents, the Treasurer and other Members elected by the Congress, on the basis of two persons of each member party, respecting the principle of gender balance. COUNCIL OF CHAIRPERSONS The Council of Chairpersons meets at least once a year. The members are the Presidents of all the member par- ties, the President of the EL and the Vice-Presidents. The Council of Chairpersons has, with regard to the Execu- tive Board, rights of initiative and objection on important political issues. The Council of Chairpersons adopts res- olutions and recommendations which are transmitted to the Executive Board, and it also decides on applications for EL membership. NETWORKS n Balkan Network n Trade Unionists n Culture Network Network WORKING GROUPS n Central and Eastern Europe n Africa n Youth n Agriculture n Migration n Latin America n Middle East n North America n Peace n Communication n Queer n Education n Public Services n Environment n Women Trafficking Member and Observer Parties The Party of the European Left (EL) is a political party at the Eu- ropean level that was formed in 2004. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Making of SYRIZA

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Panos Petrou The making of SYRIZA Published: June 11, 2012. http://socialistworker.org/print/2012/06/11/the-making-of-syriza Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. June 11, 2012 -- Socialist Worker (USA) -- Greece's Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA, has a chance of winning parliamentary elections in Greece on June 17, which would give it an opportunity to form a government of the left that would reject the drastic austerity measures imposed on Greece as a condition of the European Union's bailout of the country's financial elite. SYRIZA rose from small-party status to a second-place finish in elections on May 6, 2012, finishing ahead of the PASOK party, which has ruled Greece for most of the past four decades, and close behind the main conservative party New Democracy. When none of the three top finishers were able to form a government with a majority in parliament, a date for a new election was set -- and SYRIZA has been neck-and-neck with New Democracy ever since. Where did SYRIZA, an alliance of numerous left-wing organisations and unaffiliated individuals, come from? Panos Petrou, a leading member of Internationalist Workers Left (DEA, by its initials in Greek), a revolutionary socialist organisation that co-founded SYRIZA in 2004, explains how the coalition rose to the prominence it has today. -

The Rise of the Welfare Party in Perspective

Third World Quarterly ISSN: 0143-6597 (Print) 1360-2241 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctwq20 The political economy of Islamic resurgence in Turkey: The rise of the Welfare Party in perspective Ziya Onis To cite this article: Ziya Onis (1997) The political economy of Islamic resurgence in Turkey: The rise of the Welfare Party in perspective, Third World Quarterly, 18:4, 743-766, DOI: 10.1080/01436599714740 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01436599714740 Published online: 25 Aug 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1047 View related articles Citing articles: 61 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ctwq20 Download by: [SOAS, University of London] Date: 06 March 2017, At: 22:18 ThirdW orldQu arterly,V ol18,No4,pp743±766,1997 ThepoliticaleconomyofIslamic resurgence inTurkey:therise ofthe WelfareParty in perspective ZIÇ YA OÈ NISË Therisingelectoralfortu neso ftheWelfareP arty(Refah P artisi( RP)), a party thatd ifferentiatesitselfsh arplyfro mthe`orthodox’p artieso ftherightorlefto f thepoliticalspectrumbycam paigningex plicitlyonanIslam istp latform, constitutesth emosto bviousorv isiblesig nofIslamicresurg encein th eTurkish 1 context. Theturning-pointinth eevolutionof RP intoa majorpoliticalmove- mentcamewiththe m unicipalg overnmentelecti onsofMarch1 994during whichth epartym anagedto cap tureth emayorshipsofthetwokeym etropolitan areaso fIstanbulandA nkara.T hisvicto -

Redalyc.Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: a Case Study On

Argumentum E-ISSN: 2176-9575 [email protected] Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Brasil Sinem ARIKAN, Elif Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: A Case Study on Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Argumentum, vol. 8, núm. 1, enero-abril, 2016, pp. 115-125 Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo Vitória, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=475555256018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18315/argumentum.v8i1.11884 ARTIGO Social Welfare Provision at Local Level: A Case Study on Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality Prestação de assistência social a nível local: um estudo de caso no Município de Istambul Elif Sinem ARIKAN1 Abstract: In this article I tried to find traces of a neo-conservative model the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipal- ity in Turkey. Firstly I tried to explain significant collaboration between liberalism and conservatism in the neoliberal context. Subsequently, I tried to evaluate the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality to see the neo- conservative administration’s effects on local administrations based on market-oriented administration ra- tionale. I tried to explain that the gender discourse was strengthened because of such administration rationale. I tried to evaluate this matter profoundly. I mentioned the Ladies Commission of RP (Welfare Party) and Kadın Koordinasyon Merkezi (Women Coordination Center (WCC)) in the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality as examples of models of conservative women’s political organizations. Keywords: Neoliberalism. -

Dynamics of Youth Euroscepticism a Thesis

DYNAMICS OF YOUTH EUROSCEPTICISM A THESIS SUBMITED TO THE GARADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ÖNDER KÜÇÜKURAL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN SOCIOLOGY DECEMBER 2005 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof.Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sibel Kalaycıoğlu Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Dr. Mustafa Şen Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Galip Yalman (METU, ADM) Dr. Mustafa Şen (METU, Sociology) Assist. Prof. Dr Aykan Erdemir (METU, Sociology) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Önder Küçükural Signature : iii ABSTRACT Dynamics of Youth Euroscepticism Küçükural, Önder M.Sc., Department of Sociology Supervisor: Dr. Mustafa Şen December 2005, 138 pages The aim of this thesis is to describe the dominant features of Euroscepticism in Turkish context and to understand its main dynamics with special reference to a particular group, the youth in Turkey. A field research was conducted in order to understand youth’s EU support. -

Voter Preferences, Electoral Cleavages and Support for Islamic Parties

Voter Preferences, Electoral Cleavages and Support for Islamic Parties Sabri Ciftci Department of Political Science Kansas State University, Manhattan [email protected] Yusuf Tekin Gaziosmanpasa University, Tokat, TURKEY [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the 2009 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 2‐5 2009, Chicago, IL Abstract Increasing scholarly attention has recently been focused upon the origins and fortunes of Islamic parties. This paper examines the individual determinants of support for these parties utilizing the fifth wave of the World Values Survey. It is argued that the distribution of individual preferences along political cleavages like left‐right, secularism‐Islamism, and regime‐opposition are critical explanatory variables. The cases under investigation are Justice and Development Party (AKP) in Turkey and Party of Justice and Development (PJD) in Morocco. The results of the multinomial logit show that Islamic parties obtain support from a broad spectrum of voters and this support base is best understood in relation to the distribution of voter preferences for rival parties. Furthermore, left‐right and Islamism appear to be the most important cleavages in the electoral markets under investigation. 1 Introduction Increasing scholarly attention has recently been focused upon the origins and fortunes of Islamic parties. In this vein, a good amount of research examined the Islamic party moderation (Kalyvas, 2000; Schwedler, 2007) and their commitment to democracy (Tibbi, 2008, p. 43-48; Nasr, 2005). While there is merit in investigating these questions, it is also important to understand the microlevel foundations of support for Islamic parties. Surprisingly, little empirical research has been conducted toward this end (for an exception see Carkoglu, 2006; Tepe, 2007) and studies with a comparative orientation are rare (Garcia-Rivero and Kotze, 2007; Tepe and Baum, 2008). -

TRANSFORMATION of POLITICAL ISLAM in TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’S Pro-EU Turn

PARTY POLITICS VOL 9. No.4 pp. 463–483 Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications London Thousand Oaks New Delhi www.sagepublications.com TRANSFORMATION OF POLITICAL ISLAM IN TURKEY Islamist Welfare Party’s Pro-EU Turn Saban Taniyici ABSTRACT The recent changes in the Islamist party’s ideology and policies in Turkey are analysed in this article. The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) was ousted from power in June 1997 and was outlawed by the Consti- tutional Court (CC) in March 1998. After the ban, the WP elite founded the Virtue Party and changed policies on a number of issues. They emphasized democracy and basic human rights and freedoms in the face of this external shock. The WP’s hostile policy toward the European Union (EU) was changed. This process of change is discussed and it is argued that the EU norms presented a political opportunity structure for the party elites to influence the change of direction of the party. When the VP was banned by the CC in June 2001, the VP elites split and founded two parties which differ on a number of issues but have positive policies toward the EU. KEY WORDS European Union party change political Islam political oppor- tunity structure Turkey Introduction The Islamist Welfare Party (WP) in Turkey recently changed its decades-old policy of hostility toward the European Union (EU) and began strongly to support Turkey’s accession to the Union, thereby raising doubts about the inevitability of a civilizational conflict between Islam and the West. 1 This change was part of the party’s broader image transformation which took place after its leader, Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan,2 was forced by the Turkish political establishment to resign from a coalition government in June 1997. -

The Paradox of Adversity: New Left Party Survival and Collapse in Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina

The Paradox of Adversity: New Left Party Survival and Collapse in Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina Why do some new political parties take root after rising to electoral prominence, while others collapse after their initial success? Although strong parties are critical for stable, high-quality democracy, relatively little is known about the conditions under which strong parties emerge. The classic literature on party system development is largely based on studies of the United States and Western European countries.1 Since almost all of these polities developed stable party systems, the classic theories tend to take successful party-building for granted. While telling us much about how electoral rules, social cleavages, and access to patronage shape emerging party systems, they leave aside a more fundamental question: Under what conditions do strong parties emerge in the first place? Since the onset of the third wave of democratization, attempts to build parties have failed in much of the developing world.2 In Latin America, over 95% of the parties born during the 1980s and 1990s disbanded after failing to take off electorally, and even among the small subset of parties that attained national prominence, most collapsed shortly afterward.3 Despite the preponderance of unsuccessful new parties, existing literature on party-building in developing countries focuses overwhelmingly on the tiny fraction of new parties that survived. For example, scholars have written hundreds of book-length studies on successful new parties in Latin America but only a few such studies on unsuccessful cases.4 This inattention to unsuccessful cases is methodologically problematic: without studying cases of party-building failure, we cannot fully account for party-building success. -

What's Left of the Left: Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging

What’s Left of the Left What’s Left of the Left Democrats and Social Democrats in Challenging Times Edited by James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Duke University Press Durham and London 2011 © 2011 Duke University Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Typeset in Charis by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction: The New World of the Center-Left 1 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Part I: Ideas, Projects, and Electoral Realities Social Democracy’s Past and Potential Future 29 Sheri Berman Historical Decline or Change of Scale? 50 The Electoral Dynamics of European Social Democratic Parties, 1950–2009 Gerassimos Moschonas Part II: Varieties of Social Democracy and Liberalism Once Again a Model: 89 Nordic Social Democracy in a Globalized World Jonas Pontusson Embracing Markets, Bonding with America, Trying to Do Good: 116 The Ironies of New Labour James Cronin Reluctantly Center- Left? 141 The French Case Arthur Goldhammer and George Ross The Evolving Democratic Coalition: 162 Prospects and Problems Ruy Teixeira Party Politics and the American Welfare State 188 Christopher Howard Grappling with Globalization: 210 The Democratic Party’s Struggles over International Market Integration James Shoch Part III: New Risks, New Challenges, New Possibilities European Center- Left Parties and New Social Risks: 241 Facing Up to New Policy Challenges Jane Jenson Immigration and the European Left 265 Sofía A. Pérez The Central and Eastern European Left: 290 A Political Family under Construction Jean- Michel De Waele and Sorina Soare European Center- Lefts and the Mazes of European Integration 319 George Ross Conclusion: Progressive Politics in Tough Times 343 James Cronin, George Ross, and James Shoch Bibliography 363 About the Contributors 395 Index 399 Acknowledgments The editors of this book have a long and interconnected history, and the book itself has been long in the making. -

SYRIZA and the Rise of Radical Left-Reformism in Europe

SYRIZA and the Rise of Radical Left-Reformism in Europe Donal Mac Fhearraigh The rise of SYRIZA, Greece's Coalition ternative to austerity and the crisis of of the Radical Left, in the May elections capitalism has provoked panic among the and in polls since, has electrified the left Euro-elites and the Greek ruling class. globally. Tsipras stunned Europe's rulers when, af- The election on 6 May revealed that ter receiving the mandate from the Greek the mass of the Greek people rejected president to try and form a government, the austerity programme imposed under after New Democracy proved unable to do the Memorandum of Understanding be- so, he declared the austerity measures be- tween their government and the European ing imposed on Greece `null and void'. Union (EU) and the International Mone- The campaign of Jean-Luc Melenchon tary Fund (IMF). SYRIZA's leader, Alex in the French Presidential election shows Tsipras, has denounced the programme that the re-emergence of a left-reformist as `barbarous' and his refusal to form a current in politics isn't peculiar to Greece, coalition with the parties that support the as the EU ruling class strategy of deep- Memorandum has forced Greece into a sec- ening austerity erodes traditional political ond election on 17 June. loyalties and creates rising political polar- The last opinion poll published on Fri- isation. Overall unemployment across the day 1 June showed SYRIZA on 31.5 per- eurozone stands at its highest level since cent, its highest performance yet, and a 1999 when the currency was launched with full six points ahead of the right-wing New 17.4 million out of work2 . -

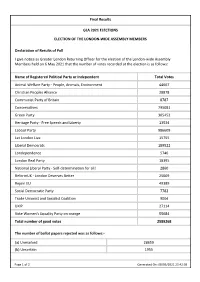

London Wide Assembly Final Results

Final Results GLA 2021 ELECTIONS ELECTION OF THE LONDON-WIDE ASSEMBLY MEMBERS Declaration of Results of Poll I give notice as Greater London Returning Officer for the election of the London-wide Assembly Members held on 6 May 2021 that the number of votes recorded at the election is as follows: Name of Registered Political Party or Independent Total Votes Animal Welfare Party - People, Animals, Environment 44667 Christian Peoples Alliance 28878 Communist Party of Britain 8787 Conservatives 795081 Green Party 305452 Heritage Party - Free Speech and Liberty 13534 Labour Party 986609 Let London Live 15755 Liberal Democrats 189522 Londependence 5746 London Real Party 18395 National Liberal Party - Self-determination for all! 2860 ReformUK - London Deserves Better 25009 Rejoin EU 49389 Social Democratic Party 7782 Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition 9004 UKIP 27114 Vote Women's Equality Party on orange 55684 Total number of good votes 2589268 The number of ballot papers rejected was as follows:- (a) Unmarked 28659 (b) Uncertain 1955 Page 1 of 2 Generated On: 08/05/2021 23:42:39 (c) Voting for too many 24212 (d) Writing identifying voter 88 (e) Want of official mark 17 Total 54931 And I do hereby declare the eleven London-wide Assembly Member seats have been allocated and filled as follows Name of Registered Political Party Seat Number or Independent 1 Green Party BERRY Sian 2 Liberal Democrats PIDGEON Caroline Valerie 3 Green Party RUSSELL Caroline 4 Conservatives BAILEY Shaun 5 Conservatives BOFF Andrew 6 Green Party POLANSKI Zack 7 Conservatives