Paperback Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography of Frank Cook's Early Library

Bibliography of Frank Cook’s Early Library Frank was a pack rat. He saved every book he ever owned. The following list represents Frank’s early readings, for the most part before his love of plants emerged. Frank gathered these books in a small library kept in his brother Ken’s basement shortly before his death. PHI provides this bibliography to friends interested in seeing some of Frank’s early influences. ALLEN, E. B. D. M. (1960). THE NEW AMERICAN POETRY (Reprint. Twelfth Printing.). GROVE PRESS. Amend, V. E. (1965). Ten Contemporary Thinkers. The Free Press. Anonymous. (1965). The Upanishads. Penguin Classics. Armstrong, G. (1969). Protest: Man against Society (2nd ed.). Bantam Books. Asimov, I. (1969). Words of Science. Signet. Atkinson, E. (1965). Johnny Appleseed. Harper & Row. Bach, R. (1989). A Gift of Wings. Dell. Baker, S. W. (1985). The Essayist (5th ed.). HarperCollins Publishers. Baricco, A. (2007). Silk. Vintage. Beavers, T. L. (1972). Feast: A Tribal Cookbook (First Edition.). Doubleday. Beck, W. F. (1976). The Holy Bible. Leader Publishing Company. Berger, T. (1982). Little Big Man. Fawcett. Bettelheim, B. (2001). The Children of the Dream. Simon & Schuster. Bolt, R. (1990). A Man for All Seasons (First Vintage International Edition.). Vintage. brautigan, R. (1981). Hawkline Monster. Pocket. Brautigan, R. (1973). A Confederate General from Big Sur (First Thus.). Ballantine. Brautigan, R. (1975). Willard and His Bowling Trophies (1st ed.). Simon & Schuster. Brautigan, R. (1976). Loading Mercury With a Pitchfork: [Poems] (First Edition.). Simon & Schuster. Brautigan, R. (1978). Dreaming of Babylon. Dell Publishing Co. Brautigan, R. (1979). Rommel Drives on Deep into Egypt. -

The Indie NEXT List MAY ’16 THIS Sleeping Giants MONTH’S #1 by Sylvain Neuvel (Del Rey, 9781101886694, $26) the Atomic Weight of Love: a Novel by Elizabeth J

The Indie NEXT List MAY ’16 THIS Sleeping Giants MONTH’S #1 By Sylvain Neuvel (Del Rey, 9781101886694, $26) The Atomic Weight of Love: A Novel By Elizabeth J. Church Recommended by Linda Bond, Auntie’s Bookstore, Spokane, WA (Algonquin Books, 9781616204846, $25.95) “Church deftly traces the life of Meridian Wallace, an intelligent Eligible: A Novel young woman who is searching for who she is and what she wants to become. As America braces for entrance into WWII, By Curtis Sittenfeld Meri falls for the ambitious Alden Whetstone, a much older but (Random House, 9781400068326, $28) brilliant scientist. Aspiring to be a ‘good wife,’ Meri abandons her own academic pursuits in ornithology to follow Alden to Los Recommended by Sharon Nagel, Boswell Book Company, Alamos, but the years that follow are filled with dashed hopes Milwaukee, WI and compromises. Over the decades of her marriage, Meri attempts to fill the void of unrealized dreams by making a home and reclaiming her sense of self. Filled with sharp, poignant prose, the novel mimics the birds Meri studies, following her as she The Versions of Us: A Novel struggles to find her wings, let go, and take flight. Church gives readers a thoughtful and thought-provoking examination of the sacrifices women make in life and the By Laura Barnett courage needed for them to soar on their own.” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 9780544634244, $26) —Anderson McKean, Page & Palette, Fairhope, AL Recommended by Kelly Estep, Carmichael’s Bookstore, The Mirror Thief: A Novel Louisville, KY By Martin Seay Imagine -

Big Tip Book for the Commodore

, THE BIG TIP BOOK FOR THE COMMODORE THE BIG TIP BOOK FOR THE COMMODORE John Annalaro and Bert Kersey BANTAM BOOKS TORONTO· !\"EW YORK· LONDON· SYDNEY· AUCKLAND Dedicated to R.A., B.A., ?A., and me. THE BIG TIP BOOK FOR THE COMMODORE A Bantam Book / June 1987 All rights reserved. Copyright © 1987 by John Annaloro and Bert Kersey. Cover design copyright © 1987 by Bantam Books. Inc. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Bantam Books, Inc. ISBN 0-553-34411-0 Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words "Bantam Books" and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, Inc., 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10103. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA B098765432 CONTENTS Preface VI 1. Getting Started 1 2. For Beginners Only: Inside Tips 11 3. Pointers for Beginners 27 4. Converting Programs to the 128 37 5. Basic Tricks 43 6. Screen and Text Graphics 53 7. Memory and Speed 61 8. Useful Applications 71 9. Protection 77 10. Advanced Programming Tricks 87 11. Machine Language 97 12. Disks and Drives 107 13. Audio and Video Communications 123 14. Printers and Printing Tips 131 Appendix A 64 and 128 Basic Commands 141 Appendix B Abbreviations for Basic Keywords 157 Appendix C Commodore Character Codes 163 Appendix D Escape Codes for the 128 169 Index 171 PREFACE 1 like programming. -

PDF Article Download

Frankfurt Book Fair Briefcase 2019 Rights Wednesday, 16th October 2019 Agents announce their top titles for the Frankfurt Book Fair (16-20 October) Aitken Alexander Girl, Woman, Other is Bernardine Evaristo's Booker-shortlisted verse novel, about an interconnected group of Black British women (agent Emma Patterson; Hamish Hamilton UK; Grove US; Eksmo Russia). Sisters is the new novel by Daisy Johnson (left), the youngest author to be shortlisted for the Booker Prize: a "taut, powerful and deeply moving" account of sibling love (agent Chris Wellbelove; Cape UK; Riverhead US; Shanghai Literature and Art China; Stock France; BTB Germany; Koppernik Netherlands; Swiat Ksiazki Poland). In Imperfect: The Power of Good Enough in the Age of Perfectionism, behavioural psychologist Tom Curran distils his research on perfectionism to show why being "just good enough" is the key to happiness, health and success (agent Chris Wellbelove; Scribner US; under offer UK). Meet Dean and his rescue kitten Nala on an adventurous and inspiring journey around the globe, in Nala's World by Dean Nicholson and Garry Jenkins (agent Lesley Thorne; Hodder UK; Grand Central US; WSOY Finland; Nona Sweden; Luebbe Germany; Sperling Italy; Meulenhoff Netherlands; Porto Portugal). Social scientist Des Fitzgerald explores the future of urban spaces in Metropolis Now (agent Chris Wellbelove; Faber UK; Basic Books US). Richard Cohen's The History Makers is an epic exploration of who gets to write the history books, and of how the lives and biases of certain storytellers continue to influence our ideas (agent the Robbins Office; Random House US; Weidenfeld UK). Ampersand Agency Eleanor Porter's debut, provisionally entitled The Ripped Earth, is the lyrical and unsparing story – based on a real event - of a young girl scapegoated for a catastrophe that divided her Elizabethan community (agent Peter Buckman; Boldwood world English). -

The Non-Western World: an Annotated Pibliograrhy for Flementary and Secondary 'Rchools

DOCIIMENT RESTIME ED 047 039 UD 011 172 AUTHOR Probandt, Puth TITLE The Non-Western World: An Annotated Pibliograrhy for Flementary and Secondary 'Rchools. INSTITIPION Massachusetts Univ., Amherst. School of rducatior. PUP FATF, May /0 NOTE g9P. AVAILABLE FFO!,! Center for International Tducation, School oc rlucation, University of Massachusets, Amherst, Mass. 01002 ($1.00) 'TOPS PRIC7 7:4RS Price MT-$.0.55 Fc-$1.20 DFSCRIPTORS African Culture, African History, African tit?rature, *AnnoiAtel Bibliographies, *Asian History, Elementary School Students, 1.atin American Culture, *Non Westerr Civilization, Resource Materials, Secondary School Students, *Social Stvaies, Spanish Culture ?lack Africa, China, India, Japan, Mexico, south America, Southeast Asia, Vietnam ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography on Asia, Africa, and Latin America contains sources primarily for elementary and secondary school students; also included are hooks for libraries and teachers. The bibliography on Asia is divided into curriculum materials and information bcoks. Some of the countries covered are: Burma; Cambodia; China; India; Japan; Korea; and Vietnam. The section on Black Africa includes a social studies curriculum for secondary students. The books on Iatin America cover Mexico as ve71. Appended are lists of audio-visual ail companies ani book publishers. (CV) S DEPARTMENT 0f NE A-TH. EDUCATION S WELFARE. OFFICE Of EDUCATION prN TNiS DOCUMENT NAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVES FROM TN E PERSON CS ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT POiNTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED 00 NOT NECES SARILV REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF ECU CATION POSITION OR POLICY THE NON-WESTERN WORLD AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY for ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS by Ruth Probandt CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION SCHOOL OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Published May 1970 Copies may be obtained from the Center for International Education, School of Education, University of Katiew3husette, Amherst, Massachusetts 01002. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

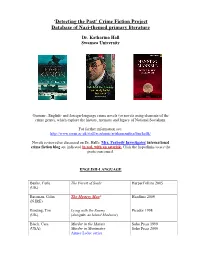

'Detecting the Past' Crime Writing Project

‘Detecting the Past’ Crime Fiction Project Database of Nazi-themed primary literature Dr. Katharina Hall Swansea University German-, English- and foreign-language crime novels (or novels using elements of the crime genre), which explore the history, memory and legacy of National Socialism. For further information see: http://www.swan.ac.uk/staff/academic/artshumanities/ltm/hallk/ Novels reviewed or discussed on Dr. Hall's 'Mrs. Peabody Investigates' international crime fiction blog are indicated in red, with an asterisk. Click the hyperlinks to see the posts concerned. ENGLISH-LANGUAGE Banks, Carla The Forest of Souls HarperCollins 2005 (UK) Bateman, Colin The Mystery Man* Headline 2009 (N.IRE) Binding, Tim Lying with the Enemy Picador 1998 (UK) (also pub. as Island Madness) Black, Cara Murder in the Marais Soho Press 1999 (USA) Murder in Montmatre Soho Press 2006 Aimee Leduc series Broderick, William The Sixth Lamentation* (see Time Warner 2004 [2003] (UK) discussion in comments section) Father Anselm series Brophy, Grace A Deadly Paradise Soho Press 2008 (US) Le Carré, John Call for the Dead* Penguin 2012 [1961] (UK) Penguin 2010 [1963] The Spy who Came in from the Cold* George Smiley #1 and #3 Sceptre 1999 [1968] A Small Town in Germany* Chabon, Michael The Final Solution Harper Perennial 2008 (USA) [2005] The Yiddish Policemen’s Union* Harper Perennial 2008 [2007] Cook, Thomas H. Instruments of Night Bantam 1999 (USA) Crispin, Edmund Holy Disorders Vintage 2007 [1946] (UK) Crombie, Deborah Where Memories Lie Macmillan 2009 [2008] -

Newly Added Paperbacks Malpass Library (Main Level) December 2015 - January 2016

Newly Added Paperbacks Malpass Library (Main Level) December 2015 - January 2016 Call Number Author Title Publisher Enum Publication Date PBK A237 ha Adler, Elizabeth House in Amalfi / St. Martin's Press, 2005 (Elizabeth A.) PBK A237 hr Adler, Elizabeth Hotel Riviera / St. Martin's Press, 2003 (Elizabeth A.) PBK A237 ip Adler, Elizabeth Invitation to Provence / St. Martin's Press, 2004 (Elizabeth A.) PBK A237 nn Adler, Elizabeth Now or never / Delacorte Press, 1997 (Elizabeth A.) PBK A237 sc Adler, Elizabeth Sailing to Capri / St. Martin's Press, 2006 (Elizabeth A.) PBK A237 st Adler, Elizabeth Summer in Tuscany / St. Martin's Press, 2002 (Elizabeth A.) PBK A277 il Agresti, Aimee. Illuminate / Harcourt, 2012 PBK A285 fl Ahern, Cecelia, 1981- Flawed / Feiwel & Friends, 2016 PBK A339 tm Albom, Mitch, 1958- Tuesdays with Morrie : an old man, a young man, Broadway Books, 2002 and life's greatest lesson / PBK A395 tp Alger, Cristina. This was not the plan : a novel / Touchstone, 2016 PBK A432 jl Allende, Isabel, Japanese lover : a novel / Atria Books, 2015 PBK A461 ll Alsaid, Adi, Let's get lost / Harlequin Teen, 2014 PBK A613 is Anner, Zach, 1984- If at birth you don't succeed : my adventures with Henry Holt and 2016 disaster and destiny / Company, PBK A917 cb 2002t Auel, Jean M. Ayla und der Clan des Bären : Roman / Wilhelm Heyne, 2002 PBK A917 mm 2002t Auel, Jean M. Ayla und die Mammutjäger : Roman / Wilhelm Heyne, 2002 PBK A917 pp 2002t Auel, Jean M. Ayla und das Tal der Grossen Mutter : Roman / Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, 2002 PBK A917 sh 2002t Auel, Jean M. -

INFORM ATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Arm Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE EXPLORATION OF MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS' INTERESTS IN AND ATTRACTIONS TO THE WRITINGS OF R. L. STINE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stacia A. -

2017 Delbarton Summer Reading List

2017 DELBARTON SUMMER READING LIST 7TH GRADE Sword of Shannara Author: Brooks, Terry ISBN 13: 978-0-345-31425-3 ISBN 10: 0-345-31425-5 Publisher: Penguin Random House Llc Publisher Imprint: Ballantine Books, Inc. 8th GRADE Enders Game Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Author: Card, Orson Scott Author: Kamkwamba, William / ISBN 13: 978-0-8125-5070-2 Mealer, Bryan ISBN 10: 0-8125-5070-6 ISBN 13: 978-0-06-173033-7 Publisher: MacMillan Higher Education ISBN 10: 0-06-173033-5 Publisher Imprint: Tor Books Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers 9th GRADE Power of One Mort Author: Courtenay, Bryce Author: Pratchett, Terry ISBN 13: 978-0-345-41005-4 ISBN 13: 978-0-06-222571-9 ISBN 10: 0-345-41005-X ISBN 10: 0-06-222571-5 Publisher: Penguin Random House Llc Publisher: HarperCollins Publishers Publisher Imprint: Ballantine Books, Inc. 10th GRADE Angela's Ashes : Memoir Travels with Charley : In Search of Author: McCourt, Frank America ISBN 13: 978-0-684-84267-7 Author: Steinbeck, John ISBN 10: 0-684-84267-X ISBN 13: 978-0-14-310700-2 Publisher: Simon & Schuster, Inc ISBN 10: 0-14-310700-3 Publisher Imprint: Touchstone Books Publisher: Penguin Random House Llc Publisher Imprint: Penguin Books, Inc 11th GRADE Old Man and the Sea Into the Wild Author: Hemingway, Ernest Author: Krakauer, Jon ISBN 13: 978-0-684-80122-3 ISBN 13: 978-0-385-48680-4 ISBN 10: 0-684-80122-1 ISBN 10: 0-385-48680-4 Publisher: Simon & Schuster, Inc Publisher: Penguin Random House Llc Publisher Imprint: Charles Scribner's & Sons Publisher Imprint: Anchor Press 12th GRADE Worst Hard Time: Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl Author: Egan, Timothy ISBN 13: 978-0-618-77347-3 ISBN 10: 0-618-77347-9 Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publisher Imprint: Mariner Books Station Eleven Cannery Row Author: Mandel, Emily Author: Steinbeck, John ISBN 13: 978-0-8041-7244-8 ISBN 13: 978-0-14-017738-1 ISBN 10: 0-8041-7244-7 ISBN 10: 0-14-017738-8 Publisher: Penguin Random House Llc Publisher: Penguin Random House Llc Publisher Imprint: Vintage Books Publisher Imprint: Penguin Books, Inc. -

2017 Annual Report INTRODUCTION

COVER Annual Report 2014 // 2015 2017 Annual Report INTRODUCTION In June 2013, a group of twelve librarians and library advocates announced the launch of a monthly list, inspired by the American Booksellers Association’s Indie Next list, dedicated to the ten favorite titles of library staff due to be published the following month. This list is the LibraryReads list, a celebration of the titles library staff love. LibraryReads is unique in that the list is not trying to pick “the best” of anything, and there are no judges or juries. The monthly list is the collective favorites of the library staff who have voted — the books we loved reading and cannot wait to share! Participation is open to everyone who works in a public library, both senior staff and new arrivals, no matter which area of the library they work in. The more the merrier — LibraryReads is designed to be inclusive, and to represent a broad range of reading tastes. One of the goals of LibraryReads is to showcase the important role public libraries play in building buzz for new books and new authors. This is already well-established in the field of children’s books – but perhaps not as widely acknowledged for adult books. OUR MISSION LibraryReads puts in list form what library staff do with patrons every day at the desk, in the community, and online: connecting readers with books, suggesting titles that will generate lively conversation among readers, and encouraging staff and readers to share further within their own reading network. LibraryReads is dedicated to celebrating reading and encouraging a sense of delight and discovery for readers of adult books. -

Palgrave Macmillan X PREFACE

The Evolution of Modern Fantasy From Antiquarianism to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series Jamie Williamson palgrave macmillan x PREFACE some cohesion. On the other hand, this approach tends toward oversim plification and breeds a kind of tunnel vision. One area which that tunnel vision has largely eliminated from consid eration in histories of fantasy has been the narrative poetry, some quite long, of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: work that engaged similar subject matter, identifieditself with similar areas of premodem and tradi tional narrative, and was widely read by many of the writers of the BAFS Introduction canon. Another area, not neglected but needing some refinement of per spective, has to do with those "epics and romances and sagas": they are gen erally alluded to rather indiscriminately as stufffrom (vaguely) "way back Charting the Terrain then." But modern access to these works is via scholarly editions, transla tions, epitomes, and retellings, themselves reflectingmodern perspectives; to readers of two centuries ago, the medieval Arthurian romances seeing print forthe first time were as new as Pride and Prejudice. My contention is that what we call modern fantasywas in facta creative extension of the he coalesc�ce of fantasy-thatcontem or ry l ter cat go y wh s _ _ r, � � �,:, � � � : antiquarian work that made these older works available. The history here, Tname most readily evokes notions of epic trilogies witb mythic then, begins in the eighteenth century. settings and characters-into a discrete genre occurred quite recently and This is, obviously, a wide arc to cover, and the following, of necessity, abruptly, a direct result of the crossing of a resurgence of interest in Ameri treats individual authors and works with brevity; detailed close readinghas can popular "Sword and Sorcery" in the early 1960s with the massive com been avoided.