Chapter 2 the Threat Section 1. Threat Offensive Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firing US 120Mm Tank Ammunition in the Leopard 2 Main Battle Tank

An advanced weapon and space systems company Firing US 120mm Tank Ammunition in the Leopard 2 Main Battle Tank NDIA Guns and Missiles Conference Harlan Huls 22 April 2008 1_T105713Cauthor.ppt 04/03/20001 1 Agenda An advanced weapon and space systems company 1. Overview of tanks and ammunition • Interoperability of the weapon and ammunition 2. Objectives of the test conducted in Denmark 3. Results of the firings in Leopard 2 with L44 and L55 weapon system 4. Conclusions 2 Description of US Tank Ammunition An advanced weapon and space systems company US 120mm Tank Ammunition Types M1028 KEWA2™ M829A3 M830A1 M1002 M831A1 M830 M908 M865 Canister APFSDS-T APFSDS-T HEAT-MP-T TPMP-T TP-T HEAT-MP-T HE-OR-T TPCSDS-T Several US ammunition types with interoperability maintained through International JCB by controlling interface features (ICD) 3 Abrams and Leopard 2 MBT With 120mm Smoothbore Cannon An advanced weapon and space systems company Leopard 2 Tanks Abrams Tanks Leo2A6 L55 Weapon (Dutch) M1A1 Abrams Leo2A5 (M256 ~ L44 Weapon) L44 Weapon (Danish) Leo2A4 M1A2 Abrams L44 Weapon (M256 ~ L44 Weapon) Several MBT configurations with 120mm weapon. Interoperability is maintained through international JCB by controlling interface features (ICD) 4 120mm Smoothbore Compatible Platforms An advanced weapon and space systems company Platform Picture Type and Country Caliber Basic Tactical Training Comments Load Rounds Rounds M1A1 Abrams 44 40 M829A3 M865 Training and USA, Australia, rounds M829A2 M831A1 Tactical designed M829A1 for 120mm Kuwait, Egypt -

Commonality in Military Equipment

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Arroyo Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Commonality in Military Equipment A Framework to Improve Acquisition Decisions Thomas Held, Bruce Newsome, Matthew W. -

Projected Acquisition Costs for the Army's Ground Combat Vehicles

Projected Acquisition Costs for the Army’s Ground Combat Vehicles © MDart10/Shutterstock.com APRIL | 2021 At a Glance The Army operates a fleet of ground combat vehicles—vehicles intended to conduct combat opera- tions against enemy forces—and plans to continue to do so. Expanding on the Army’s stated plans, the Congressional Budget Office has projected the cost of acquiring such vehicles through 2050. Those projections include costs for research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) and for procurement but not the costs of operating and maintaining the vehicles. CBO’s key findings are as follows: • Total acquisition costs for the Army’s ground combat vehicles are projected to average about $5 billion per year (in 2020 dollars) through 2050—$4.5 billion for procurement and $0.5 billion for RDT&E. • The projected procurement costs are greater (in constant dollars) than the average annual cost for such vehicles from 2010 to 2019 but approximately equal to the average annual cost from 2000 to 2019 (when spending was boosted because of operations in Iraq). • More than 40 percent of the projected acquisition costs of Army ground combat vehicles are for Abrams tanks. • Most of the projected acquisition costs are for remanufactured and upgraded versions of current vehicles, though the Army also plans to acquire an Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle, which will replace the Bradley armored personnel carrier; an Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle, which will replace the M113 armored personnel carrier; and a new Mobile Protected Firepower tank, which will be lighter than an Abrams tank. • The Army is also considering developing an unmanned Decisive Lethality Platform that might eventually replace Abrams tanks. -

COMBAT DAMAGE ASSESSMENT TEAM A-10/GAU-8 LOW ANGLE FIRINGS VERSUS INDIVIDUAL SOVIET TANKS (February - March 1978)

NPS56-79-005 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California COMBAT DAMAGE ASSESSMENT TEAM A-10/GAU-8 LOW ANGLE FIRINGS VERSUS INDIVIDUAL SOVIET TANKS (February - March 1978) R.H.S. Stolfi J.E. Clemens R.R. McEachir August 1979 Approved for public release; distribution unlimited •7 Prepared for: A-10 System Program Office Wright Patterson Air Force Base Ohio 45433 FEDDOCS D 208.1 4/2:NPS-56-79-005 r NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California Rear Admiral Tyler F. - Dedman Jark R Rnrct1 nn Superintendent Borsting jjj^J' he r ed he rein P was supported by the A-10 System Program OfficI Wr?nht p fl r 9 ,T r F° r " BaSe Ohio ' The " ' reproduction of allai\ oror'oarpart of thisf"reportt' is authorized. UNCLASSIFIED SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE (Whan Dili Bnlarad) READ INSTRUCTIONS REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE BEFORE COMPLETING FORM NO 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER t. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVT ACCESSION NPS56-79-005 S. TYPE OF REPORT ft PERIOD COVERED 4. TITLE (and Subtltlt) Special Report for Period Combat Damage Assessment Team A-10/GAU-8 February - March 1978 Low Angle Firings Versus Individual Soviet 6. PERFORMING ORG. REPORT NUMBER Tanks (February - March 1978) B. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBERf*.) 7. AUTHOR^; R.H.S. Stolfi None J.E. Clemens R.R. McEachin 10. PROGRAM ELEMENT, PROJECT, TASK 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS AREA ft WORK UNIT NUMBERS Naval Postgraduate School F 47615-78-5209 and Monterey, California 93940 FY 7621-78-90220 12. REPORT DATE II. CONTROLLING OFFICE NAME AND ADDRESS A-10 System Program Office January 1979 Wright Patterson Air Force Base 13. -

Characteristics of Torsion Bar Suspension Elasticity in Mbts and the Assessment of Realized Solutions

Scientific-Technical Review,vol.LIII,no.2,2003 67 UDC: 623.438.3(047)=20 COSATI: 19-03, 20-11 Characteristics of torsion bar suspension elasticity in MBTs and the assessment of realized solutions Rade Stevanović, BSc (Eng)1) On the basis of available data and known equations, basic parameters of suspension systems in a number of main bat- tle tanks with torsion bar suspension are determined. On the basis of the conclusions obtained from the presented graphs and the table, the characteristics of torsion bar suspension elasticity in some main types of tanks are assessed. Key words: main battle tank, suspension, torsion bar, elasticity, work load capacity. Principal symbols Union), the US and Germany, in one type of French and one Japanese main battle tank, and in some British tanks for a – swing arm length export as well. All other producers from other countries, c – torsion bar spring rate whose main battle tanks had the torsion bar suspension, Crs – reduced torsion bar spring rate in the static wheel mainly used the licence or the experience of the previously position, suspension characteristic derivate in the mentioned countries. static wheel position The characteristics of torsion bar suspension systems in d – torsion bar diameter main battle tanks in serial production until the 60s for the fd – positive vertical spring travel, static-to-bump use in NATO forces (M-47 and M-48) and the Warsaw movement Treaty countries (T-54 and T-55), were of nearly the same fs, fm – rebound and total vertical spring travel (low) level, but still higher than the British tank Centurion Fs – vertical wheel load on the road wheel in the static characteristics, with BOGEY suspension, which was also wheel position in serial production at that time. -

The Army's M-1 Abrams, M-2/M-3 Bradley, and M-1126 Stryker: Background and Issues for Congress

The Army’s M-1 Abrams, M-2/M-3 Bradley, and M-1126 Stryker: Background and Issues for Congress (name redacted) Specialist in Military Ground Forces April 5, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44229 The Army’s M-1 Abrams, M-2/M-3 Bradley, and M-1126 Stryker Summary The M-1 Abrams Tank, the M-2/M-3 Bradley Fighting Vehicle (BFV), and the M-1126 Stryker Combat Vehicle are the centerpieces of the Army’s Armored Brigade Combat Teams (ABCTs) and Stryker Brigade Combat Teams (SBCTs). In addition to the military effectiveness of these vehicles, Congress is also concerned with the economic aspect of Abrams, Bradley, and Stryker recapitalization and modernization. Due to force structure cuts and lack of Foreign Military Sales (FMS) opportunities, Congress has expressed a great deal of concern with the health of the domestic armored combat vehicle industrial base. ABCTs and SBCTs constitute the Army’s “heavy” ground forces; they provide varying degrees of armored protection and mobility that the Army’s light, airborne (parachute), and air assault (helicopter transported) infantry units that constitute Infantry Brigade Combat Teams (IBCTs) do not possess. These three combat vehicles have a long history of service in the Army. The first M-1 Abrams Tank entered service with the Army in 1980; the M-2/M-3 Bradley Fighting Vehicle in 1981; and the Stryker Combat Vehicle in 2001. Under current Army modernization plans, the Army envisions all three vehicles in service with Active and National Guard forces beyond FY2028. There are several different versions of these vehicles in service. -

Tank Gunnery

Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com MHI Copy 3 FM 17-12 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY FIELD MANUAL TANK GUNNERY HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY NOVEMBER 1964 Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com PREPARE TO FIRE Instructional Card (M41A3, M48, and M60 Tanks) TANK COMMANDER GUNNER DRIVER LOADER Commond: PREPARE TO Observe looder's actionr in Cleon periscopes, Check indicotor tape for FIRE. making check of replenisher in. lower seat, close proper amount of recoil oil Inspect coaxial machine- dicotor tope. Clean nd inspect hoatch, nd turn in replenilher. Check posi- gun ond telescope ports gunner s direct-fire sights. Check on master switch. tion of breechblock crank to ensure gun shield operaoion of sight covers if op. stop. Open breech (assisted cover is correctly posi- cable. Check instrument lights. by gunner); inspect cham- tioned ond clomps are Assist loader in opening breech. ber ond tube, and clote secure. Clean exterior breech. Check coxial lenses and vision devices. mochinegun and adjust and clean ond inspect head space if opplicble. commander's direct-fire Check coaxial machinegun sight(s). Inspect cupolao mount ond odjust solenoid. sowed ammunilion if Inspect turret-stowed am. applicable. munitlon. Command: CHECK FIR- Ploce main gun safety in FIRE Start auxiliary Place moin gun safety ING SWITCHES. position if located on right side engine (moin en- in FIREposition if loated If main gun has percus- of gun. Turn gun switch ON. gin. if tank has on left side of gun. If sion mechanism, cock gun Check firing triggers on power no auxiliary en- moin gun hoaspercussion for eoch firing check if control handle if applicable. -

115 Mm, 120 Mm & 125 Mm Tank Guns

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS ANNEX D 115 MM, 120 MM & 125 MM TANK GUNS The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) is an expert organisation working to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards, in close partnership with states, the UN and other human security actors. Based at the Maison de la paix in Geneva, the GICHD employs around 55 staff from over 15 countries with unique expertise and knowledge. bhenkz2) Our work is made possible by core contributions, project funding and in-kind support from more than 20 governments and organisations. photobucket The research project was guided and advised by a group of 18 international experts dealing with credit: weapons-related research and practitioners who address the implications of explosive weapons in humanitarian, policy, advocacy and legal fields. This document contributes to the research of the (Photo characterisation of explosive weapons (CEW) project in 2015-2016. gun main its firing Characterisation of explosive weapons study, annex D – 115 m m, 120 mm & 125 mm tank guns GICHD, Geneva, February 2017 T-90MS-V ISBN: 978-2-940369-65-2 Tank Russian The content of this publication, its presentation and the designations employed do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) regarding the legal status of image: any country, territory or armed group, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All content remains the sole responsibility of the GICHD. Cover CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 TANK GUNS 6 High Explosive Tank Gun Ammunition 8 TANK GUN CASE STUDIES 11 Brief Descriptions 11 CASE STUDIES 13 Case Study 1 13 Case Study 2 17 Case Study 3 21 Case Study 4 24 Case Study 5 26 Annex D Contents 3 INTRODUCTION This study examines the characteristics, use and effects of tank guns and tank projectiles. -

The Bradley Fighting Vehicle-The Troops Love It Just Like Its Partner-In

The Bradley Fighting Vehicle-The Troops Love It Just like its partner-in-combat the Ml Abrams tank, the Army's new M2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle is rolling off the assembly line in grow ing numbers and finding an enthusias tic welcome in the units where it is be ing assigned. From the battalion com manders down to the squad leaders who fight from the Bradley there is high praise for its speed, agility, fire power and protection from artillery fragments and small caliber weapons. Also, just like the Abrams tank, the Bradley has been subject to a great deal of uninformed and polemical crit icism leading to its current less-than optimal press image. In truth, the Bradley, now fielded in 17 battalions, is a very successful piece of equip ment. It does what it was intended to do and does it very well. It deserves more objective treatment by the press and other critics who do not under stand its function. The Bradley exists to provide infan trymen and cavalry scouts a protected fighting platform on the battlefield where they function as partners of a combined-arms team, closely integrat ed with tanks, artillery, aviation and air defense weapons. For the first time our infantry soldiers can move into a new dimension-aboard a protective vehicle from which they can fight the enemy, with the firepower, agility and speed which assures continuous effec tiveness on a modern battlefield. This is not just a matter of getting the infantry to the battle. It is the de mand that infantry and tanks fight to gether, that both be there offering their strengths and protecting the oth er's weaknesses. -

Leopard 2 - Tank Variants Summary As Of: 21 Feb 11

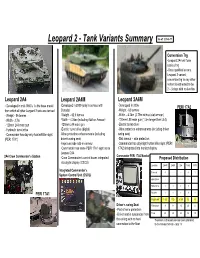

Leopard 2 - Tank Variants Summary As of: 21 Feb 11 Conversion Trg -Leopard 2A4 will form basis of trg -Once qualified on any Leopard 2 variant, conversion trg to any other variant is estimated to be 2 – 3 days with no live fire Leopard 2A4 Leopard 2A4M Leopard 2A6M - Developed in mid-1980’s. Is the base model -Developed in 2009 (only in service with -Developed in 2006 PERI 17A2 from which all other Leopard 2 tank are derived Canada) -Weight - 63 tonnes - Weight - 56 tonnes -Weight – 62.5 tonnes -Width – 4.24m (3.75m without slat armour) - Width - 3.7m -Width – 4.05m (including Add-on Armour) -120mm L55 main gun (1.3m longer than L44) - 120mm L44 main gun -120mm L44 main gun -Electric turret drive - Hydraulic turret drive -Electric turret drive (digital) -Mine protection enhancements (including driver - Commander has day-only hunter/Killer sight -Mine protection enhancements (including swing seat) (PERI 17A1) driver’s swing seat) -Slat armour – side protection -Improved side add-on-armour -Commander has day/night hunter killer sight (PERI -Commander has same PERI 17A1 sight as on 17A2) integrated into monitor display Leopard 2A4 2A4 Crew Commander’s Station -Crew Commander’s control boxes integrated Commander PERI 17A2 Monitor Proposed Distribution into digital display (CSCU) Location 2A4M 2A6M 2A4 Total ARV Integrated Commander’s Fenced 4 - - 4 1 System Control Unit (CSCU) Ops Stock - - - - - Reference 1 1 1 3 - PERI 17A1 Borden 1 1 1 3 1 Gagetown* 5 (2) 7 (2) 20 (9) 32 4 Driver’s swing Seat Edmonton 9 11 20 40 4 -Part of mine protection -

Crescent Moon Rising? Turkish Defence Industrial Capability Analysed

Volume 4 Number 2 April/May 2013 Crescent moon rising? Turkish defence industrial capability analysed SETTING TOOLS OF FIT FOR THE SCENE THE TRADE PURPOSE Urban combat training Squad support weapons Body armour technology www.landwarfareintl.com LWI_AprMay13_Cover.indd 1 26/04/2013 12:27:41 Wescam-Land Warfare Int-ad-April 2013_Layout 1 13-03-07 2:49 PM Page 1 IDENTIFY AND DOMINATE L-3’s MXTM- RSTA: A Highly Modular Reconnaissance, Surveillance and Target Acquisition Sighting System • Configurable as a Recce or independent vehicle sighting system • Incorporate electro-optical/infrared imaging and laser payloads that match your budget and mission portfolio • 4-axis stabilization allows for superior on-the-move imaging capability • Unrivaled ruggedization enables continuous performance under the harshest climates and terrain conditions MX-RSTA To learn more, visit www.wescam.com. WESCAM L-3com.com LWI_AprMay13_IFC.indd 2 26/04/2013 12:29:01 CONTENTS Front cover: The 8x8 Pars is one of a growing range of armoured vehicles developed in Turkey. (Image: FNSS/Lorna Francis) Editor Darren Lake. [email protected] Deputy Editor Tim Fish. [email protected] North America Editor Scott R Gourley. [email protected] Tel: +1 (707) 822 7204 European Editor Ian Kemp. [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL COMMENT Staff Reporters Beth Stevenson, Jonathan Tringham Export drive Defence Analyst Joyce de Thouars 4 NEWS Contributors • Draft RfP outlines US Army AMPV requirements Claire Apthorp, Gordon Arthur, Mike Bryant, Peter Donaldson, • Navistar delivers first Afghan armoured cabs Jim Dorschner, Christopher F Foss, • Canada solicits bids for integrated soldier system Helmoed Römer Heitman, Rod Rayward • KMW seals Qatar tank and artillery deal Production Manager • Dutch Cheetah air defence guns sold to Jordan David Hurst Sub-editor Adam Wakeling 7 HOME GROWN Commercial Manager Over the past three decades, Turkey has gradually Jackie Hall. -

KV-IV in Bolt Action

KV-IV in Bolt action Points: Inexperienced (650 points) includes 15 crewmen and 1 commissar Damage Value: 10+ (Heavy Tank) Options • Spotter +10 points • Four man rocket reload crew + 28 points Weapons Hard point Weapons Range Shots Pen Special Rules Bow Bow MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, forward arc Forward turret Medium Anti Tank Gun 60” 1 +5 Team, Fixed, forward, right, left arcs, HE(1”) coax MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, forward, right, left arcs rear MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, right, left arcs Forward sub turret Vehicle flame throwers 12” D6+1 +3 Team, Fixed, Forward, right, left arcs, Flamethrower Pintel HMG 36” 3 1 Team, Fixed, Flak Deck MG turret Twin MMG 36” 10 - Team, Fixed, Right arc Deck MG turret Twin MMG 36” 10 - Team, Fixed, Left arc Midships turret Twin heavy Howitzer (36”-84”) 2 HE Team, Fixed, forward, Left, right arcs, 72” Howitzer HE(4”) Rear MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, Left Right arcs Pintel HMG 36” 3 1 Team, Fixed, Flak Midships sub Light Anti Tank gun 48” 1 +4 Team, Fixed, forward, right, left arcs, turret: HE(1”) Coax MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, Left Right arcs Rear MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, Left Right arcs Deck MG turret Twin MMG 36” 10 - Team, Fixed, Right arc Deck MG turret Twin MMG 36” 10 - Team, Fixed, Left arc Rear turret Medium Anti Tank Gun 60” 1 +5 Team, Fixed, rear, right, left arcs, HE(1”) coax MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, rear, right, left arcs rear MMG 36” 5 - Team, Fixed, left, right arcs Katyusha Multiple launcher (12”-72”) 1 HE Team, Fixed, rear, right, left arcs, HE(3”) Special Rules Slow: maximum move of 6 inches Poor turning circle: instead of pivoting 90 degrees the front of the tank can be moved up to 3 inches to the left or right when the tank pivots.