Singleton, David TITLE Language Across Cultures. Proceedings of a Symposium (St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Flavour of Hampton

A Flavour of Hampton Hampton,Friends of The NewLane Memorial Hampshire Library A FLAVOUR OF HAMPTON Recipes and Reminiscences Sponsored By The Friends of the Lane Memorial Library Hampton, New Hampshire 1979 To the many good cooks and good Friends who worked to make this cookbook a success, we extend warm thanks and appreciation. Over a hundred persons contributed recipes-- and you will recognize among them Hampton neigh- bors who are not members of the Friends, but who share our commitment to the Lane Memorial Library and its varied services. r Special thanks go to the many Friends who so generously gave their time and talents to A Flavour of Hampton: who helped to plan it, or r solicited recipes, or assisted in editing, proof- reading, indexing, distributing, promoting or selling the book. M And let's all backspace for a moment and remember the typists, who produced a polished manuscript under deadline pressure. A word of caution to the reader: cooks work in different ways, so please read a recipe carefully before commencing it. w Illustrations by Ina Chiaramitaro IW Calligraphy by Arlene Tompson PI 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS NOTES AND LEGENDS By Mary Ellen James, Marianne Jewell and Connie Call Lane Memorial Library and the Friends 14 Thorvald the Viking 29 The Founding of Hampton 46 Goody Cole 77 Jonathan Moulton And His Pact With The Devil 112 The Lane Family 138 Appetizers & Beverages SAUSAGE BREAD - hors d' oeuvre Bonnie Sheets (Make ahead if desired) 1 lb. hot Italian sausage ½ lb. Provolone cheese - shredded 1/4 c. grated Italian cheese 6 eggs 1 stick pepperoni, diced 3 frozen bread dough - raised Skin sausage and fry 10-15 min. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Inside: Shrimp Cake Topped with a Lemon Aioli, Caulilini and Roasted Tomato Medley and Pommes Fondant

Epicureans March 2019 Upcoming The President’s Message Hello to all my fellow members and enthusiasts. We had an amazing meeting this February at The Draft Room Meetings & located in the New Labatt Brew House. A five course pairing that not only showcased the foods of the Buffalo Events: region, but also highlighted the versatility and depth of flavors craft beers offer the pallet. Thank you to our keynote speaker William Keith, Director of Project management of BHS Foodservice Solutions for his colloquium. Also ACF of Greater Buffalo a large Thank-You to the GM Brian Tierney, Executive Chef Ron Kubiak, and Senior Bar Manager James Czora all with Labatt Brew house for the amazing service and spot on pairing of delicious foods and beer. My favorite NEXT SOCIAL was the soft doughy pretzel with a perfect, thick crust accompanied by a whole grain mustard, a perfect culinary MEETING amalgamation! Well it’s almost spring, I think I can feel it. Can’t wait to get outside at the Beer Garden located on the Labatt house property. Even though it feels like it’ll never get here thank goodness for fun events and GREAT FOOD!! This region is not only known for spicy wings, beef on weck and sponge candy, but as a Buffalo local you can choose from an arsenal of delicious restaurants any day of the week. To satisfy what craves you, there are a gamut of food trends that leave the taste buds dripping Buffalo never ceases to amaze. From late night foods, food trucks, micro BHS FOODSERVICE beer emporiums, Thai, Polish, Lebanese, Indian, on and on and on. -

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (From Either the French Chair Cuite = Cooked Meat, Or the French Cuiseur De

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (from either the French chair cuite = cooked meat, or the French cuiseur de chair = cook of meat) is the branch of cooking devoted to prepared meat products such as sausage primarily from pork. The practice goes back to ancient times and can involve the chemical preservation of meats; it is also a means of using up various meat scraps. Hams, for instance, whether smoked, air-cured, salted, or treated by chemical means, are examples of charcuterie. The French word for a person who prepares charcuterie is charcutier , and that is generally translated into English as "pork butcher." This has led to the mistaken belief that charcuterie can only involve pork. The word refers to the products, particularly (but not limited to) pork specialties such as pâtés, roulades, galantines, crépinettes, etc., which are made and sold in a delicatessen-style shop, also called a charcuterie." SAUSAGE A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted (Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means) meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ A sausage is a food usually made from ground meat , often pork , beef or veal , along with salt, spices and other flavouring and preserving agents filed into a casing traditionally made from intestine , but sometimes synthetic. Sausage making is a traditional food preservation technique. Sausages may be preserved by curing , drying (often in association with fermentation or culturing, which can contribute to preservation), smoking or freezing. -

Spices from the East: Papers in Languages of Eastern Indonesia

Sp ices fr om the East Papers in languages of eastern Indonesia Grimes, C.E. editor. Spices from the East: Papers in languages of Eastern Indonesia. PL-503, ix + 235 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2000. DOI:10.15144/PL-503.cover ©2000 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Also in Pacific Linguistics Barsel, Linda A. 1994, The verb morphology of Mo ri, Sulawesi van Klinken, Catherina 1999, A grammar of the Fehan dialect of Tetun: An Austronesian language of West Timor Mead, David E. 1999, Th e Bungku-Tolaki languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia Ross, M.D., ed., 1992, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 2. (Papers by Sarah Bel1, Robert Blust, Videa P. De Guzman, Bryan Ezard, Clif Olson, Stephen J. Schooling) Steinhauer, Hein, ed., 1996, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 3. (Papers by D.G. Arms, Rene van den Berg, Beatrice Clayre, Aone van Engelenhoven, Donna Evans, Barbara Friberg, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Paul R. Kroeger, DIo Sirk, Hein Steinhauer) Vamarasi, Marit, 1999, Grammatical relations in Bahasa Indonesia Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia, Southeast and South Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. -

St. Patrick Was Not Irish. He Was Born Maewyn Succat in Britain

St. Patrick Was Not Irish. He Was Born Maewyn Succat In Britain St. Patrick’s Day kicks off a worldwide celebration that is also known as the Feast of St. Patrick. On March 17th, many will wear green in honor of the Irish and decorate with shamrocks. In fact, the wearing of the green is a tradition that dates back to a story written about St. Patrick in 1726. St. Patrick (c. AD 385–461) was known to use the shamrock to illustrate the Holy Trinity and to have worn green clothing. They’ll revel in the Irish heritage and eat traditional Irish fare, too. In the United States, St. Patrick’s Day has been celebrated since before the country was formed. While the holiday has been a bit more of a rowdy one, with green beer, parades, and talk of leprechauns, in Ireland, it the day is more of a solemn event. It wasn’t until broadcasts of the events in the United States were aired in Ireland some of the Yankee ways spread across the pond. One tradition that is an Irish-American tradition not common to Ireland is corned beef and cabbage. In 2010, the average Irish person aged 15+ drank 11.9 litres (3 gallons) of pure alcohol, according to provisional data. That’s the equivalent of about 44 bottles of vodka, 470 pints or 124 bottles of wine. There is a famous Irish dessert known as Drisheen, a surprisingly delicious black pudding. The leprechaun, famous to Ireland, is said to grant wishes to those who can catch them. -

Wedding Menu 2020/21

W E D D I N G M E N U 2 0 2 0 / 2 1 S U P P L I E D B Y CANAPÉS £6.95 for a choice of 3 / £2.25 each additional MEAT -Quail scotch egg, curry mayo -Sesame tempura chicken balls, ketchup manis -Boerewors sausage, chilli jam glaze -Mini pork and chorizo burger, stilton cheese sauce -Mini steak and chips, Rosedew ketchup -Beef brisket bon bon, sweetcorn puree VEGGIE -Welsh rarebit muffins, onion jam -Red onion and goats cheese tart -Mini vegetable spring roll, sweet chilli (Vegan) -Beetroot, feta and crispy onion tartlets -Mini falafel burgers, red pepper salsa (Vegan) -Garlic mushroom arrancini, aioli FISH -Cockle and bacon tart -Kuro prawns, lime and ginger mayo -Mini fish and chips, pea purée -Beetroot gravlax blini, horseradish cream, caperberries -Thai fishcake lollipops, sweet chilli BREADS Chefs selection of freshly baked breads, served with salty churned butter portions. (GF/Vegan options available) Add extra's for £1.50 per table -Flavoured butter slates -Extra virgin olive oil and balsamic pearls -Houmous: plain, smoked or red pepper -Garlic and herb aioli GRAZING BOARDS £8 per person Choose 4 items from ‘mains’ section and 2 from the ‘sides’ section All meat options have veggie alternatives available on request {MAINS} -Selection of antipasti meats -Mini pork pies -Chicken liver parfait -Ham hock terrine -Calamari -Crispy cod goujons -Goats cheese and caramelised onion quiche (V) -Marinated seared halloumi (Ve) -Roasted Mediterranean veg skewers (Ve) -Melting camembert {SIDES} -Garlic and herb olives -Chefs mixed salad -Spiced -

Toward a Phonological Reconstruction of Proto-Sula (PDF)

W O R K I N G P A P E R S I N L I N G U I S T I C S The notes and articles in this series are progress reports on work being carried on by students and faculty in the Department. Because these papers are not finished products, readers are asked not to cite from them without noting their preliminary nature. The authors welcome any comments and suggestions that readers might offer. Volume 46(8) December 2015 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA HONOLULU 96822 An Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Institution University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa: Working Papers in Linguistics 46(8) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS FACULTY 2015 Victoria B. Anderson Andrea Berez-Kroeker Derek Bickerton (Emeritus) Robert A. Blust Lyle Campbell Kenneth W. Cook (Adjunct) Kamil Deen Patricia J. Donegan (Chair) Katie K. Drager Emanuel J. Drechsel (Adjunct) Michael L. Forman (Emeritus) Gary Holton Roderick A. Jacobs (Emeritus) William O’Grady Yuko Otsuka Ann Marie Peters (Emeritus) Kenneth L. Rehg (Adjunct) Lawrence A. Reid (Emeritus) Amy J. Schafer (Acting Graduate Chair) Albert J. Schütz, (Emeritus, Editor) Jacob Terrell James Woodward Jr. (Adjunct) #ii TOWARD A PHONOLOGICAL RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-SULA1 TOBIAS BLOYD ABSTRACT. This paper describes the primary dialect division in Sula, an under-documented language of eastern Indonesia. It uses the Comparative Method with new primary data to describe the protolanguage and its transformations, and in the process helps to narrow the regional literature gap. Collins (1981) placed Sula within a Buru–Sula–Taliabo subgroup of Proto–West–Central Maluku with- in the Austronesian family. -

Chapter 18 : Sausage the Casing

CHAPTER 18 : SAUSAGE Sausage is any meat that has been comminuted and seasoned. Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means. A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ In simplest terms, sausage is ground meat that has been salted for preservation and seasoned to taste. Sausage is one of the oldest forms of charcuterie, and is made almost all over the world in some form or the other. Many sausage recipes and concepts have brought fame to cities and their people. Frankfurters from Frankfurt in Germany, Weiner from Vienna in Austria and Bologna from the town of Bologna in Italy. are all very famous. There are over 1200 varieties world wide Sausage consists of two parts: - the casing - the filling THE CASING Casings are of vital importance in sausage making. Their primary function is that of a holder for the meat mixture. They also have a major effect on the mouth feel (if edible) and appearance. The variety of casings available is broad. These include: natural, collagen, fibrous cellulose and protein lined fibrous cellulose. Some casings are edible and are meant to be eaten with the sausage. Other casings are non edible and are peeled away before eating. 1 NATURAL CASINGS: These are made from the intestines of animals such as hogs, pigs, wild boar, cattle and sheep. The intestine is a very long organ and is ideal for a casing of the sausage. -

To Download Application Form for West

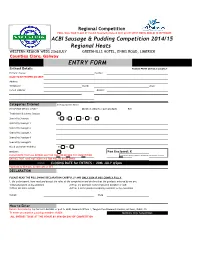

Regional Competition FINAL (NATIONALWILL TAKE FINAL PLACE WILL AT TAKEFood PLACE& Hospitality AT SHOP Ireland 2012 @2014 RDS @ in CITY September) WEST HOTEL DUBLIN IN SEPTEMBER ACBI Sausage & Pudding Competition 2014/15 Regional Heats WESTERN REGION WEDS 23rdJULY GREENHILLS HOTEL, ENNIS ROAD, LIMERICK Counties Clare, Galway ENTRY FORM Entrant Details PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Entrant's Name: Position: NAME TO BE PRINTED ON CERT: Address: Telephone: (work) (fax) e-mail address: Mobile: Categories Entered (tick appropriate boxes) PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Member entry fee (per product) €45 Traditional Butchers Sausage Speciality Sausage 1 2 3 4 5 Speciality Sausage 1 Speciality Sausage 2 Speciality Sausage 3 Speciality Sausage 4 Speciality Sausage 5 Black and White Pudding B W Drisheen Fee Enclosed: € PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL ENTRIES MUST BE PAID FOR BEFORE THE COMPETITION Please make cheques payable to Associated Craft Butchers of Ireland ENTRIES THAT HAVE NOT BEEN PAID FOR WILL BE DISALLOWED >>>> CLOSING DATE for ENTRIES : 20th JULY @5pm Payment by Cheque, Credit card or EFT DECLARATION PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING DECLARATION CAREFULLY AND ONLY SIGN IF YOU COMPLY FULLY. I, the undersigned, have read and accept the rules of the competition and declare that the products entered by me are; 1) Manufactured on my premises 2) That the premises is the registered member of ACBI 3) That the meat is Irish 4) That it is the product normally available to my customers Signed Date How to Enter Return this form by by fax to 01-8682822 or post to ACBI, Research Office 1, Teagasc Food Research Centre, Ashtown, Dublin 15. -

ENTRY FORM Entrant Details PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Entrant's Name: Position: NAME to BE PRINTED on CERT: Address: Telephone: (Work) (Fax) E-Mail Address: Mobile

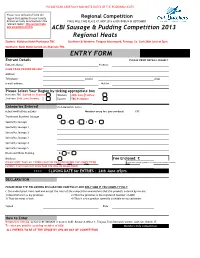

PLEASE READ CAREFULLY AND NOTE DATES OF THE REGIONAL HEATS Please note on back of form the region that applies to your county. Regional Competition Entries will only be accepted in the (NATIONAL FINAL WILL FINAL TAKE WILL PLACE TAKE AT PLACESHOP 2013 AT SHOP @ RDS 2012 DUBLIN @ RDS IN inSEPTEMBER September) relevant region. We cannot make any exceptions to this ACBI Sausage & Pudding Competition 2013 Regional Heats Eastern: Maldron Hotel Portlaoise TBC Southern & Western: Teagasc Moorepark, Fermoy, Co. Cork 26th June at 3pm Northern: Bush Hotel Carrick-on-Shannon TBC ENTRY FORM Entrant Details PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Entrant's Name: Position: NAME TO BE PRINTED ON CERT: Address: Telephone: (work) (fax) e-mail address: Mobile: Please Select Your Region by ticking appropriate box Northern TBC Carrick on Shannon Western 26th June FermoyFermoy Southern 26th June Fermoy Eastern TBC Portlaoise Categories Entered (tick appropriate boxes) PLEASE PRINT DETAILS CLEARLY Member entry fee (per product) €45 Traditional Butchers Sausage Speciality Sausage 1 2 3 4 5 Speciality Sausage 1 Speciality Sausage 2 Speciality Sausage 3 Speciality Sausage 4 Speciality Sausage 5 Black and White Pudding B W Drisheen Fee Enclosed: € PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL ENTRIES MUST BE PAID FOR BEFORE THE COMPETITION Please make cheques payable to Associated Craft Butchers of Ireland ENTRIES THAT HAVE NOT BEEN PAID FOR WILL BE DISALLOWED >>>> CLOSING DATE for ENTRIES : 24th June @5pm DECLARATION PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING DECLARATION CAREFULLY AND ONLY SIGN IF YOU COMPLY FULLY. I, the undersigned, have read and accept the rules of the competition and declare that the products entered by me are; 1) Manufactured on my premises 2) That the premises is the registered member of ACBI 3) That the meat is Irish 4) That it is the product normally available to my customers Signed Date How to Enter Return this form by by fax to 01-8682820 or post to ACBI, Research Office 1, Teagasc Food Research Centre, Ashtown, Dublin 15. -

Word-Prosodic Systems of Raja Ampat Languages

Word-prosodic systems of Raja Ampat languages PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Dr. D.D. Breimer, hoogleraar in de faculteit der Wiskunde en Natuurwetenschappen en die der Geneeskunde, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 9 januari 2002 te klokke 15.15 uur door ALBERT CLEMENTINA LUDOVICUS REMIJSEN geboren te Merksem (België) in 1974 Promotiecommissie promotores: Prof. Dr. V.J.J.P. van Heuven Prof. Dr. W.A.L. Stokhof referent: Dr. A.C. Cohn, Cornell University overige leden: Prof. Dr. T.C. Schadeberg Prof. Dr. H. Steinhauer Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6006 Trans 10 fax: +31 30 253 6000 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.let.uu.nl/LOT/ Cover illustration: Part of the village Fafanlap (Misool, Raja Ampat archipelago, Indonesia) in the evening light. Photo by Bert Remijsen (February 2000). ISBN 90-76864-09-8 NUGI 941 Copyright © 2001 by Albert C.L. Remijsen. All rights reserved. This book is dedicated to Lex van der Leeden (1922-2001), with friendship and admiration Table of contents Acknowledgements vii Transcription and abbreviations ix 1 Introduction 1 2 The languages of the Raja Ampat archipelago 5 2.1. About this chapter 5 2.2. Background 6 2.2.1. The Austronesian and the Papuan languages, and their origins 6 2.2.2. The South Halmahera-West New Guinea subgroup of Austronesian 8 2.2.2.1. In general 8 2.2.2.2. Within the South Halmahera-West New Guinea (SHWNG) subgroup 9 2.2.2.3.