Preface: the History of Black Pudding in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Tipperary Heritage Plan 2012-2016

South Tipperary Heritage Plan 2012-2016 “Heritage is not so much a thing of the past but of the present and the future.” — Michael Starrett Chief Executive, the Heritage Council South Tipperary Heritage Plan 2012-2016 TEXT COMPILED AND EDITED BY JANE-ANNE CLEARY, LABHAOISE MCKENNA, MIEKE MUYLLAERT AND BARRY O’REILLY IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE SOUTH TIPPERARY HERITAGE FORUM PRODUCED BY LABHAOISE MCKENNA, HERITAGE OFFICER, SOUTH TIPPERARY COUNTY COUNCIL © 2012 South Tipperary County Council This publication is available from: The Heritage Officer South Tipperary County Council County Hall, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary Phone: 052 6134650 Email: [email protected] Web: www.southtippheritage.ie All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission in writing of the publisher. Graphic Design by Connie Scanlon and print production by James Fraher, Bogfire www.bogfire.com This paper has been manufactured using special recycled fibres; the virgin fibres have come from sustainably managed forests; air emissions of sulphur, CO2 and water pollution have been limited during production. CAPTIONS INSIDE FRONT COVER AND SMALL TITLE PAGE: Medieval celebrations along Clonmel Town Wall during Festival Cluain Meala. Photograph by John Crowley FRONTISPIECE: Marlfield Church. Photograph by Danny Scully TITLE PAGE: Cashel horse taken on Holy Cross Road. Photograph by Brendan Fennessey INSIDE BACK COVER: Hot Horse shoeing at Channon’s Forge, Clonmel. Photograph by John D Kelly. BACK COVER: Medieval celebrations along Clonmel’s Town Wall as part of Festival Cluain Meala. -

Zur Vollversion 3 1 Tells Her All About ( Typical Emma Is on Holiday in England

Lesespurlandkarte British food VORSCHAU Denise Sarrach: Lesespurgeschichten Englisch Landeskunde 5–7 Lesespurgeschichten Englisch Sarrach: Denise Verlag Auer © zur Vollversion3 1 Lesespurgeschichte British food British food Emma is on holiday in England. Her aunt Stacey tells her all about typical (typisch) British food. To get to know what Emma learns about British food, start at number 1. 1 This is what British people eat for breakfast: small sausages. We eat them with baked beans (weiße Bohnen mit Tomatensoße). Can you find them? 2 The English word for your German ‘Chips’ is crisps. This is not fish ’n’ chips. 3 This is shortbread. Some say it’s only a biscuit (Keks), but I think it’s more than that. Another food we like is black pudding. 4 Chicken Tikka Masala is an Indian dish (Speise). Indian culture and food are very popular in England. We love this dish. 5 That’s scrambled eggs, correct. They’re great! The most famous thing we eat for lunch is fish ’n’ chips. 6 We might eat toast on Sundays, but I said Sunday roast, not toast. 7 These are beans as well, but they’re jellybeans. They’re sweets. We don’t eat them for breakfast. 8 This is a chocolate egg. Very good for Easter (Ostern), but not typically British. 9 This is tea, but it’s not black tea. Other kinds of tea are not very familiar (bekannt) here. 10 Sunday roast is a very traditional meal. It’s meat (Fleisch) and vegetables (Gemüse). Another tradition is our black tea for teatime. 11 Yes, thisVORSCHAU is black pudding. -

We're A' Jock Tamson's Bairns

Some hae meat and canna eat, BIG DISHES SIDES Selkirk and some wad eat that want it, Frying Scotsman burger £12.95 Poke o' ChipS £3.45 Buffalo Farm beef burger, haggis fritter, onion rings. whisky cream sauce & but we hae meat and we can eat, chunky chips Grace and sae the Lord be thankit. Onion Girders & Irn Bru Mayo £2.95 But 'n' Ben Burger £12.45 Buffalo Farm beef burger, Isle of Mull cheddar, lettuce & tomato & chunky chips Roasted Roots £2.95 Moving Munros (v)(vg) £12.95 Hoose Salad £3.45 Wee Plates Mooless vegan burger, vegan haggis fritter, tomato chutney, pickles, vegan cheese, vegan bun & chunky chips Mashed Tatties £2.95 Soup of the day (v) £4.45 Oor Famous Steak Pie £13.95 Served piping hot with fresh baked sourdough bread & butter Steak braised long and slow, encased in hand rolled golden pastry served with Champit Tatties £2.95 roasted roots & chunky chips or mash Cullen skink £8.95 Baked Beans £2.95 Traditional North East smoked haddock & tattie soup, served in its own bread Clan Mac £11.95 bowl Macaroni & three cheese sauce with Isle of Mull, Arron smoked cheddar & Fresh Baked Sourdough Bread & Butter £2.95 Parmesan served with garlic sourdough bread Haggis Tower £4.95 £13.95 FREEDOM FRIES £6.95 Haggis, neeps and tatties with a whisky sauce Piper's Fish Supper Haggis crumbs, whisky sauce, fried crispy onions & crispy bacon bits Battered Peterhead haddock with chunky chips, chippy sauce & pickled onion Trio of Scottishness £5.95 £4.95 Haggis, Stornoway black pudding & white pudding, breaded baws, served with Sausage & Mash -

Inside: Shrimp Cake Topped with a Lemon Aioli, Caulilini and Roasted Tomato Medley and Pommes Fondant

Epicureans March 2019 Upcoming The President’s Message Hello to all my fellow members and enthusiasts. We had an amazing meeting this February at The Draft Room Meetings & located in the New Labatt Brew House. A five course pairing that not only showcased the foods of the Buffalo Events: region, but also highlighted the versatility and depth of flavors craft beers offer the pallet. Thank you to our keynote speaker William Keith, Director of Project management of BHS Foodservice Solutions for his colloquium. Also ACF of Greater Buffalo a large Thank-You to the GM Brian Tierney, Executive Chef Ron Kubiak, and Senior Bar Manager James Czora all with Labatt Brew house for the amazing service and spot on pairing of delicious foods and beer. My favorite NEXT SOCIAL was the soft doughy pretzel with a perfect, thick crust accompanied by a whole grain mustard, a perfect culinary MEETING amalgamation! Well it’s almost spring, I think I can feel it. Can’t wait to get outside at the Beer Garden located on the Labatt house property. Even though it feels like it’ll never get here thank goodness for fun events and GREAT FOOD!! This region is not only known for spicy wings, beef on weck and sponge candy, but as a Buffalo local you can choose from an arsenal of delicious restaurants any day of the week. To satisfy what craves you, there are a gamut of food trends that leave the taste buds dripping Buffalo never ceases to amaze. From late night foods, food trucks, micro BHS FOODSERVICE beer emporiums, Thai, Polish, Lebanese, Indian, on and on and on. -

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (From Either the French Chair Cuite = Cooked Meat, Or the French Cuiseur De

CHAPTER-2 Charcutierie Introduction: Charcuterie (from either the French chair cuite = cooked meat, or the French cuiseur de chair = cook of meat) is the branch of cooking devoted to prepared meat products such as sausage primarily from pork. The practice goes back to ancient times and can involve the chemical preservation of meats; it is also a means of using up various meat scraps. Hams, for instance, whether smoked, air-cured, salted, or treated by chemical means, are examples of charcuterie. The French word for a person who prepares charcuterie is charcutier , and that is generally translated into English as "pork butcher." This has led to the mistaken belief that charcuterie can only involve pork. The word refers to the products, particularly (but not limited to) pork specialties such as pâtés, roulades, galantines, crépinettes, etc., which are made and sold in a delicatessen-style shop, also called a charcuterie." SAUSAGE A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted (Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means) meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ A sausage is a food usually made from ground meat , often pork , beef or veal , along with salt, spices and other flavouring and preserving agents filed into a casing traditionally made from intestine , but sometimes synthetic. Sausage making is a traditional food preservation technique. Sausages may be preserved by curing , drying (often in association with fermentation or culturing, which can contribute to preservation), smoking or freezing. -

BREAKFAST MENUS Continental Buffet Breakfast Freshly Baked Mini

BREAKFAST MENUS Continental Buffet Breakfast Freshly baked mini Bridor pastries, 100% butter croissants, mini fruit scones or cranberry and pecan scones with preserves and sweet muffins Contains: ①(WHEAT)③⑥⑦⑧ (ALMOND, PECAN, HAZELNUT) Seasonal fruit platters with Glenilen yoghurt and crunchy granola Contains: ① (OATS, BARLEY, RYE) ⑦⑧ (WALNUT, ALMOND) Freshly brewed tea and coffee to include a variety of herbal and fruit infused teas Contains: No Allergens Keeling’s fresh pressed orange juice and carafes of mint and cucumber water Contains: No Allergens Networking grab and go breakfast Seasonal fresh whole fruit and selection of fruit juices Contains: No Allergens Freshly brewed premium coffee, hot chocolate and a variety of traditional, herbal and fruit infused tea Contains: ⑦ Assorted Danish pastries, muffins, fruit bread and savoury filled croissants Contains: ①(WHEAT)③⑥⑦⑧ (ALMOND, PECAN, HAZELNUT) Macadamia and white chocolate chip cookies Contains: ①(WHEAT)③⑥⑦⑧(MACADAMIA) Little pots of vanilla yoghurt and bircher muesli Contains: ① (OATS, BARLEY, RYE) ⑦⑧ (WALNUT, ALMOND) Blended smoothie of mango, pineapple, banana, and passionfruit Contains: No Allergens Selection of tapas meats and smoked cheese Contains: ⑦⑫ Additional Items Mini smoked streaky bacon butty, Ballymaloe relish Contains: ①(WHEAT)③⑦⑩ Gourmet sausage and black pudding roll Contains: ① (WHEAT, OATS) ③⑦⑫ Pancetta, spring onion and asparagus frittata Contains: ③ Scrambled free range eggs and avocado smash brioche Contains: ①(WHEAT)③⑦ Full Irish Buffet Dry cured bacon, Loughnane’s -

St. Patrick Was Not Irish. He Was Born Maewyn Succat in Britain

St. Patrick Was Not Irish. He Was Born Maewyn Succat In Britain St. Patrick’s Day kicks off a worldwide celebration that is also known as the Feast of St. Patrick. On March 17th, many will wear green in honor of the Irish and decorate with shamrocks. In fact, the wearing of the green is a tradition that dates back to a story written about St. Patrick in 1726. St. Patrick (c. AD 385–461) was known to use the shamrock to illustrate the Holy Trinity and to have worn green clothing. They’ll revel in the Irish heritage and eat traditional Irish fare, too. In the United States, St. Patrick’s Day has been celebrated since before the country was formed. While the holiday has been a bit more of a rowdy one, with green beer, parades, and talk of leprechauns, in Ireland, it the day is more of a solemn event. It wasn’t until broadcasts of the events in the United States were aired in Ireland some of the Yankee ways spread across the pond. One tradition that is an Irish-American tradition not common to Ireland is corned beef and cabbage. In 2010, the average Irish person aged 15+ drank 11.9 litres (3 gallons) of pure alcohol, according to provisional data. That’s the equivalent of about 44 bottles of vodka, 470 pints or 124 bottles of wine. There is a famous Irish dessert known as Drisheen, a surprisingly delicious black pudding. The leprechaun, famous to Ireland, is said to grant wishes to those who can catch them. -

It's All About the Pastry…. Pies, Pasties & More

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE PASTRY…. PIES, PASTIES & MORE Our pork pies use traditional hot water crust pastry, shortcrust pastry in all our pies & pasties & quiches (unless stated), & puff pastry for sausage rolls & slices. For our vegetarian products, our pastry does not contain animal fats. We use a low salt gravy in all our beef pies. Individual pies – 9cm diameter. Sharing or Large pies – 14cm. THE PORK PIE – the pie that started PROPER PIES. AVAILABLE LARGE (600G+) & SMALL BEEF PIES LARGE: 7.50€ Individual pies – 3.20€ - or sharing pies – 7.80€ SMALL: 3.50€ STEAK STEAK & KIDNEY SPECIAL EDITION PORK PIES MEAT & POTATO Available as a large pie MINCE BEEF & ONION SPECIAL EDITION PIES PORK & BLACK PUDDING PIE: 8€ SCOTCH (hot water crust pastry) Sharing pies….to share or not to share? GALA PIE – pork pie & boiled egg: 7.80€ BEEF STEW: 8€ Also available as GALA LOAF: 18.50€ BEEF & BLUE CHEESE: 8.70€ CHICKEN PIES BEEF & CORFU BREWERY DARK (RED) BEER: 8.70€ Individual pies – 3€ - or sharing pies – 7.50€ ROASTED VEGETABLE: 8€ VEGETARIAN CREAMY CHICKEN CREAMY VEGETABLE PIE: 3€ CHICKEN & BACON VEGETARIAN ROLL: 1.50€ CHICKEN & MUSHROOM CHEESE & ONION SLICE: 2.50€ CHICKEN & LEEK ROASTED VEGETABLE PIE: 8€ CHICKEN BALTI QUICHES 10 inch, from 9€, depending on filling…. PUDDINGS ADD MEAT, FISH, VEGETABLES, CHEESE…. Suet pastry, ready steamed – 4€ STEAK STEAK & KIDNEY PASTIES, SAUSAGE ROLLS & MORE AND WHY NOT TRY….. WEST COUNTRY PASTY (Cornish-style): 3€ OUR SPICY PICKLED ONIONS – great with BREAKFAST PIE (sausage & Heinz beans): 3€ our Pork Pies, Sliced Ham, Quiche…. CHEESE & ONION SLICE: 2.50€ Approximate net weight: 300g SAUSAGE ROLL: 1.50€ 3€ PER JAR SCOTCH EGG: 2.50€ . -

Product List ’20 Pies Our Award-Winning, Delicious & Meaty Homemade Pies Are Made Only from the Finest Ingredients

Product list ’20 pies Our award-winning, delicious & meaty homemade pies are made only from the finest ingredients. hot eating 200g pies steak and potato steak and gravy* steak and kidney minced beef and onion chicken and mushroom large 5” beef and gravy (290g) 12 inch pies steak and kidney steak and potato steak and ale* * Proud class and gold medal winners beef and gravy chicken and mushroom at the British Pie Awards 2019 & 2020 chicken and smoked bacon lamb and mint specials 8 inch cutting pies 2.27kg cold eating speciality chicken and ham 500g pies farmhouse pork chicken and cider apple stuffing bury pie with black pudding* UNCOOKED PIES charcoal ploughmans pork, chicken and cider apple stuffing* steak and kidney 200g x 24 huntsman pie with chicken and stuffing long gala (2.72kg) steak and potato 200g x 24 stilton topped pork pie SPECIALS AVAILABLE ON REQUEST beef and onion 200g x 24 charcoal ploughmans* steak and stilton 200g beef and gravy 200g x 24 red leicester and pickle steak and ale 200g chicken and mushroom 200g x 24 all of our meat pies and pastries can be supplied frozen and uncooked ideal for caterers in boxes of 24, 50 for sausage rolls and individual for catering size pasties pork pies quiche traditional pasty individual 112g our quiches are made daily peppered steak pasty 11oz / 308g and contain fresh ingredients 1lb 454g UNCOOKED PASTIES chilli beef pasty x 30 individual - 200g bacon and cheese pasty x 24 5 inch - 290g cheese and onion pasty x 30 12 inch - 2.2kg cheese and ham pasty x 30 vegetable pasty x 30 VARIETIES -

Copyright by Colleen Anne Hynes 2007

Copyright by Colleen Anne Hynes 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Colleen Anne Hynes certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “Strangers in the House”: Twentieth Century Revisions of Irish Literary and Cultural Identity Committee: Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, Supervisor Barbara Harlow, Co-Supervisor Kamran Ali Ann Cvetkovich Ian Hancock “Strangers in the House”: Twentieth Century Revisions of Irish Literary and Cultural Identity by Colleen Anne Hynes, B.S.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2007 Acknowledgements This dissertation project would not have been possible with the support, wisdom and intellectual generosity of my dissertation committee. My two supervisors, Elizabeth Butler Cullingford and Barbara Harlow, introduced me to much of the literature and many of the ideas that make up this project. Their direction throughout the process was invaluable: they have been, and continue to be, inspirational teachers, scholars and individuals. Kamran Ali brought both academic rigor and a sense of humor to the defense as he pushed the manuscript beyond its boundaries. Ann Cvetkovich translated her fresh perspective into comments on new directions for the project and Ian Hancock was constantly generous with his resources and unique knowledge of the Irish Traveller community. Thanks too to my graduate school colleagues, who provided constructive feedback and moral support at every step, and who introduced me to academic areas outside of my own, especially Miriam Murtuza, Miriam Schacht, Veronica House, George Waddington, Neelum Wadhwani, Lynn Makau, Jeanette Herman, Ellen Crowell and Lee Rumbarger. -

Chapter 18 : Sausage the Casing

CHAPTER 18 : SAUSAGE Sausage is any meat that has been comminuted and seasoned. Comminuted means diced, ground, chopped, emulsified or otherwise reduced to minute particles by mechanical means. A simple definition of sausage would be ‘the coarse or finely comminuted meat product prepared from one or more kind of meat or meat by-products, containing various amounts of water, usually seasoned and frequently cured .’ In simplest terms, sausage is ground meat that has been salted for preservation and seasoned to taste. Sausage is one of the oldest forms of charcuterie, and is made almost all over the world in some form or the other. Many sausage recipes and concepts have brought fame to cities and their people. Frankfurters from Frankfurt in Germany, Weiner from Vienna in Austria and Bologna from the town of Bologna in Italy. are all very famous. There are over 1200 varieties world wide Sausage consists of two parts: - the casing - the filling THE CASING Casings are of vital importance in sausage making. Their primary function is that of a holder for the meat mixture. They also have a major effect on the mouth feel (if edible) and appearance. The variety of casings available is broad. These include: natural, collagen, fibrous cellulose and protein lined fibrous cellulose. Some casings are edible and are meant to be eaten with the sausage. Other casings are non edible and are peeled away before eating. 1 NATURAL CASINGS: These are made from the intestines of animals such as hogs, pigs, wild boar, cattle and sheep. The intestine is a very long organ and is ideal for a casing of the sausage. -

Copyrighted Material

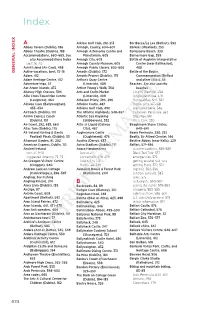

Index A Arklow Golf Club, 212–213 Bar Bacca/La Lea (Belfast), 592 Abbey Tavern (Dublin), 186 Armagh, County, 604–607 Barkers (Wexford), 253 Abbey Theatre (Dublin), 188 Armagh Astronomy Centre and Barleycove Beach, 330 Accommodations, 660–665. See Planetarium, 605 Barnesmore Gap, 559 also Accommodations Index Armagh City, 605 Battle of Aughrim Interpretative best, 16–20 Armagh County Museum, 605 Centre (near Ballinasloe), Achill Island (An Caol), 498 Armagh Public Library, 605–606 488 GENERAL INDEX Active vacations, best, 15–16 Arnotts (Dublin), 172 Battle of the Boyne Adare, 412 Arnotts Project (Dublin), 175 Commemoration (Belfast Adare Heritage Centre, 412 Arthur's Quay Centre and other cities), 54 Adventure trips, 57 (Limerick), 409 Beaches. See also specifi c Aer Arann Islands, 472 Arthur Young's Walk, 364 beaches Ahenny High Crosses, 394 Arts and Crafts Market County Wexford, 254 Aille Cross Equestrian Centre (Limerick), 409 Dingle Peninsula, 379 (Loughrea), 464 Athassel Priory, 394, 396 Donegal Bay, 542, 552 Aillwee Cave (Ballyvaughan), Athlone Castle, 487 Dublin area, 167–168 433–434 Athlone Golf Club, 490 Glencolumbkille, 546 AirCoach (Dublin), 101 The Atlantic Highlands, 548–557 Inishowen Peninsula, 560 Airlink Express Coach Atlantic Sea Kayaking Sligo Bay, 519 (Dublin), 101 (Skibbereen), 332 West Cork, 330 Air travel, 292, 655, 660 Attic @ Liquid (Galway Beaghmore Stone Circles, Alias Tom (Dublin), 175 City), 467 640–641 All-Ireland Hurling & Gaelic Aughnanure Castle Beara Peninsula, 330, 332 Football Finals (Dublin), 55 (Oughterard),