1.E SPRING POPULATION SURVEY of EMPEROR GEESE (Chen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology, Harvest, and Use of Harbor Seals and Sea Lions: Interview Materials from Alaska Native Hunters

Ecology, Harvest, and Use of Harbor Seals and Sea Lions: Interview Materials from Alaska Native Hunters Technical Paper No. 249 Terry L. Haynes and Robert J. Wolfe, Editors Funded through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Subsistence Harvest and Monitor System (No. 50ABNF700050) and Subsistence Seal and Sea Lion Research (NA66FX0476) Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Juneau, Alaska August 1999 The Alaska Department of Fish and Game conducts all programs and activities free from discrimination on the basis of sex, color, race, religion, national origin, age, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. For information on alternative formats available for this and other department publications, please contact the department ADA Coordinator at (voice) 907-465-4120, (TDD) 1-800-478-3648 or (FAX) 907-586-6595. Any person who believes s/he has been discriminated against should write to: ADF&G, P.O. Box 25526, Juneau, Alaska 99802-5526; or O.E.O., U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. 20240. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 1 ALEUTIAN ISLANDS ............................................................................................... 11 Akutan................................................................................................................. 11 Atka .................................................................................................................... -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

PROCEEDINGS OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM VoL 109 WMhington : 1959 No. 3412 MARINE MOLLUSCA OF POINT BARROW, ALASKA Bv Nettie MacGinitie Introduction The material upon which this study is based was collected by G. E. MacGinitie in the vicinity of Point Barrow, Alaska. His work on the invertebrates of the region (see G. E. MacGinitie, 1955j was spon- sored by contracts (N6-0NR 243-16) between the OfRce of Naval Research and the California Institute of Technology (1948) and The Johns Hopkins L^niversity (1949-1950). The writer, who served as research associate under this project, spent the. periods from July 10 to Oct. 10, 1948, and from June 1949 to August 1950 at the Arctic Research Laboratory, which is located at Point Barrow base at ap- proximately long. 156°41' W. and lat. 71°20' N. As the northernmost point in Alaska, and representing as it does a point about midway between the waters of northwest Greenland and the Kara Sea, where collections of polar fauna have been made. Point Barrow should be of particular interest to students of Arctic forms. Although the dredge hauls made during the collection of these speci- mens number in the hundreds and, compared with most "expedition standards," would be called fairly intensive, the area of the ocean ' Kerckhofl Marine Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. 473771—59 1 59 — 60 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. los bottom touched by the dredge is actually small in comparison with the total area involved in the investigation. Such dredge hauls can yield nothing comparable to what can be obtained from a mudflat at low tide, for instance. -

An Annotated Checklist of the Marine Macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T

NOAA Professional Paper NMFS 19 An annotated checklist of the marine macroinvertebrates of Alaska David T. Drumm • Katherine P. Maslenikov Robert Van Syoc • James W. Orr • Robert R. Lauth Duane E. Stevenson • Theodore W. Pietsch November 2016 U.S. Department of Commerce NOAA Professional Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic Papers NMFS and Atmospheric Administration Kathryn D. Sullivan Scientific Editor* Administrator Richard Langton National Marine National Marine Fisheries Service Fisheries Service Northeast Fisheries Science Center Maine Field Station Eileen Sobeck 17 Godfrey Drive, Suite 1 Assistant Administrator Orono, Maine 04473 for Fisheries Associate Editor Kathryn Dennis National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Science and Technology Economics and Social Analysis Division 1845 Wasp Blvd., Bldg. 178 Honolulu, Hawaii 96818 Managing Editor Shelley Arenas National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Publications Office 7600 Sand Point Way NE Seattle, Washington 98115 Editorial Committee Ann C. Matarese National Marine Fisheries Service James W. Orr National Marine Fisheries Service The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS (ISSN 1931-4590) series is pub- lished by the Scientific Publications Of- *Bruce Mundy (PIFSC) was Scientific Editor during the fice, National Marine Fisheries Service, scientific editing and preparation of this report. NOAA, 7600 Sand Point Way NE, Seattle, WA 98115. The Secretary of Commerce has The NOAA Professional Paper NMFS series carries peer-reviewed, lengthy original determined that the publication of research reports, taxonomic keys, species synopses, flora and fauna studies, and data- this series is necessary in the transac- intensive reports on investigations in fishery science, engineering, and economics. tion of the public business required by law of this Department. -

17 R.-..Ry 19" OCS Study MMS 88-0092

OCISt.., "'1~2 Ecologic.1 Allociue. SYII'tUsIS 0' ~c. (I( 1'B IPnCfS OP MOISE AlII) DIsmuA1K2 a, IIUc. IIADLOft m.::IIIDA1'IONS or lUIS SIA PI.-IPms fr •• LGL Muke ••••• rda Aaeoc:iat_, Inc •• 505 "-t IIortbera Lllbta .1••••,"Sait. 201 ABdaonp, AlMke 99503 for u.s. tIl_rala •••••••••• Seni.ce Al_1taa o.t.r CoIItlM11tal Shelf legion U.S. u.,c. of Iat.dor ••• 603, ,., EMt 36tla A.-... A8eb0ra•• , Aluke 99501 Coatraet _. 14-12-00CU-30361 LGL •••••• 'U 821 17 r.-..ry 19" OCS Study MMS 88-0092 StAllUIS OWIUOlMUc. 011'DB &IIBCfI ,. 11010 AlII) DIS'ftJU8CB 011llAJoa IWJLOU'r COIICIII'DArIa. OW101. SB&PIDU&DI by S.R. Johnson J.J. Burnsl C.I. Malme2 R.A. Davis LGL Alaska Research Associatel, Inc. 505 West Northern Lights Blv~., Suite 201 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 for u.S. Minerals Management Service Alaskan Outer Continental Shelf Region U.S. Dept. of Interior Room 603, 949 East 36th Avenue Anchorage, Alaska 99508 Contract no. 14-12-0001-30361 LGL Rep. No. TA 828 17 February 1989 The opinionl, findings, conclusions, or recolmBendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Dept. of the Interior. nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. 1 Living Resources Inc., Fairbanks, AK 2 BBN Systems and Technologies Corporation, Cambridge, MA Table of Contents ii 'UIU or cc»mll UBLBor cowmll ii AIS'lIAC'f • · . vi Inter-site Population Sensitivity Index (IPSI) vi Norton Basin Planning Area • • vii St. -

Ring of Fire Proposed RMP and Final EIS- Volume 1 Cover Page

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management N T OF M E TH T E R A IN P T E E D R . I O S R . U M 9 AR 8 4 C H 3, 1 Ring of Fire FINAL Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement and Final Environmental Impact Statement and Final Environmental Management Plan Resource Proposed Ring of Fire Volume 1: Chapters 1-3 July 2006 Anchorage Field Office, Alaska July 200 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMMENT 6 Volume 1 The Bureau of Land Management Today Our Vision To enhance the quality of life for all citizens through the balanced stewardship of America’s public lands and resources. Our Mission To sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. BLM/AK/PL-06/022+1610+040 BLM File Photos: 1. Aerial view of the Chilligan River north of Chakachamna Lake in the northern portion of Neacola Block 2. OHV users on Knik River gravel bar 3. Mountain goat 1 4. Helicopter and raft at Tsirku River 2 3 4 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Ring of Fire Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement Prepared By: Anchorage Field Office July 2006 United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Alaska State Office 222 West Seventh Avenue, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 995 13-7599 http://www.ak.blm.gov Dear Reader: Enclosed for your review is the Proposed Resource Management Plan and Final Environmental Impact Statement (Proposed RMPIFinal EIS) for the lands administered in the Ring of Fire by the Bureau of Land Management's (BLM's) Anchorage Field Office (AFO). -

Publications in Biological Oceanography, No

National Museums National Museum of Canada of Natural Sciences Ottawa 1971 Publications in Biological Oceanography, No. 3 The Marine Molluscs of Arctic Canada Elizabeth Macpherson CALIFORNIA OF SCIK NCCS ACADEMY |] JAH ' 7 1972 LIBRARY Publications en oceanographie biologique, no 3 Musees nationaux Musee national des du Canada Sciences naturelles 1. Belcher Islands 2. Evans Strait 3. Fisher Strait 4. Southampton Island 5. Roes Welcome Sound 6. Repulse Bay 7. Frozen Strait 8. Foxe Channel 9. Melville Peninsula 10. Frobisher Bay 11. Cumberland Sound 12. Fury and Hecia Strait 13. Boothia Peninsula 14. Prince Regent Inlet 15. Admiralty Inlet 16. Eclipse Sound 17. Lancaster Sound 18. Barrow Strait 19. Viscount Melville Sound 20. Wellington Channel 21. Penny Strait 22. Crozier Channel 23. Prince Patrick Island 24. Jones Sound 25. Borden Island 26. Wilkins Strait 27. Prince Gustaf Adolf Sea 28. Ellef Ringnes Island 29. Eureka Sound 30. Nansen Sound 31. Smith Sound 32. Kane Basin 33. Kennedy Channel 34. Hall Basin 35. Lincoln Sea 36. Chantrey Inlet 37. James Ross Strait 38. M'Clure Strait 39. Dease Strait 40. Melville Sound 41. Bathurst Inlet 42. Coronation Gulf 43. Dolphin and Union Strait 44. Darnley Bay 45. Prince of Wales Strait 46. Franklin Bay 47. Liverpool Bay 48. Mackenzie Bay 49. Herschel Island Map 1 Geographical Distribution of Recorded Specimens CANADA DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, MINES AND RESOURCES CANADASURVEYS AND MAPPING BRANCH A. Southeast region C. North region B. Northeast region D. Northwest region Digitized by tlie Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from California Academy of Sciences Library http://www.archive.org/details/publicationsinbi31nati The Marine Molluscs of Arctic Canada Prosobranch Gastropods, Chitons and Scaphopods National Museum of Natural Sciences Musee national des sciences naturelles Publications in Biological Publications d'oceanographie Oceanography, No. -

A Synopsis of the Marine Prosobranch Gastropod and Bivalve Mollusks in Alaskan Waters

A synopsis of the marine prosobranch gastropod and bivalve mollusks in Alaskan waters Item Type Thesis Authors Foster, Nora Rakestraw Download date 10/10/2021 02:40:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/5221 A SYNOPSIS OF THE MARINE PROSOBRANCH GASTROPOD AND BIVALVE MOLLUSKS IN ALAbRAN ’-.ArLRS RECOMMENDED: Chairman, Advisory Committee Program Head Director of Division of Marine Science APPROVED: Dean of the College of Environmental Sciences Date Vice Chancellor for Research and Advanced Stud A SYNOPSIS OF THE NARINE PROSOBRANCH GASTROPOD AND BIVALVE MOLLUSKS IN ALASKAN WATERS A THESIS Presented to the Faculty University of Alaska in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Decree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Nora Rakestraw Foster, B.S. V- > • Fairbanks, Alaska December, 197 9 Abstract This studv presents information on the tnxonomv and distribution of the marine prosobranch gastropod and bivalve mollusks from the waters surrounding Alaska. Three hundred fifty-two species of prosobranch gastropods and 202 species of bivalves are reported from these waters. Over 3,000 lots of specimens, representing 330 species and literature sources form the basis of this study. References, synonymy, geographic and bathymetric ranges are provided for each species. Characteristics used to identify the species of 66 genera are presented in tabular form. The greatest number of species is reported from the southern Bering Sea, <-ite fewest from the Beaufort Sea. Most of the species have wide ranges in the eastern or western Pacific. New collecting records reported here extend the known ranges of 27 species. Eight species were previously unknown from Alaskan waters. -

Population and Status of Emperor Geese Along the North Side of the Alaska Peninsula MARGARET R

Population and status of Emperor Geese along the north side of the Alaska Peninsula MARGARET R. PETERSEN and ROBERTE. GILL, Jr. The Emperor Goose Anser canagicus is 1,900 km2. They are characterized by ex found primarily in maritime areas through tensive intertidal areas of mud, sand, and out its annual cycle (Bellrose 1976; Palmer sand-gravel, and are partly protected from 1976; Eisenhauer & Kirkpatrick 1977). In the open sea by barrier islands or sand North America, the breeding population is spits. centred on the coastal fringe of the Nelson Lagoon, the principal study area, Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Alaska. Birds is part of the Port Moller complex. The winter along the Alaska Peninsula, in the lagoon is shallow, with extensive flats Kodiak Archipelago, and throughout the (47% of the lagoon) exposed at mean low Aleutian Islands. The estuaries along tide. The study area has been described in the north side of the Alaska Peninsula are detail by Gill & Jorgensen (1979) and the main staging areas during migration in Petersen (1980, 1981). spring and autumn, during which tens of thousands of birds concentrate for brief periods (US Fish and Wildlife Service Methods [U.S.F.W.S.], unpub.). Recent publications (Bellrose 1976; Populations and age determination Eisenhauer & Kirkpatrick 1977) cite King and Lensink’s (1971) estimate of an The total number of Emperor Geese along autumn population of 150,000 Emperor the north side of the Alaska Peninsula was Geese in Alaska. Since 1971 this estimate estimated in autumn 1979 and 1980, and in has not been refined and there has been no spring 1977 and 1981, from aerial surveys serious effort to assess the population sta flown at heights of 50-150 m over the tus of this goose. -

Alaska Russia

410 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 9, Chapter 8 19 SEP 2021 178°W 174°W 170°W 166°W 162°W 158°W KOTZEBUE SOUND T I A R R USSIA T S G 16190 N I R E B Cape Rodney 16206 Nome 64°N NORTON SOUND 16200 St. Lawrence Island 16220 ALASKA 16240 BERING SEA Cape Romanzof 16304 St. Matthew Island Bethel E T O L Nunivak Island I N S T 60°N R A I T 16322 16300 16323 KUSKOKWIM BAY Dillingham 16011 Naknek 16305 16315 16381 BRISTOL BAY 16338 Pribilof Islands 16343 16382 16380 16363 Port Moller 56°N 16520 U N I M A K P A S S 16006 S D N A 52°N S L I N I A U T A L E NORTH PA CIFIC OCEAN Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 9—Chapter 8 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 9, Chapter 8 ¢ 411 Bering Sea (1) This chapter describes the north coast of the Alaska 25 66°18.05'N., 169°25.87'W. 27 65°56.20'N., 169°16.11'W. Peninsula, the west coast of Alaska including Bristol Precautionary Area E Bay, Norton Sound and the numerous bays indenting 26 65°56.20'N., 169°25.87'W. 29 65°45.52'N., 169°25.87'W. these areas. Also described are the Pribilof Islands and Nunivak, St. Matthew and St. Lawrence Islands. The 27 65°56.20'N., 169°16.11'W. -

Bristol Bay Flight Log 2006

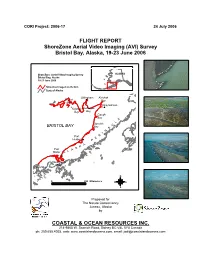

CORI Project: 2006-17 24 July 2006 FLIGHT REPORT ShoreZone Aerial Video Imaging (AVI) Survey Bristol Bay, Alaska, 19-23 June 2006 ShoreZone Aerial Video Imaging Survey ALASKA Bristol Bay, Alaska 19-23 June 2006 Shoreline Imaged (2,412 km) State of Alaska Dillingham Kvichak Togiak # Bay Bay King Salmon # Kulukak Nushagak Bay Bay Egegik Bay A Ugashik L BRISTOL BAY Bay U S N I Port N # E Heiden P A K S Port A Moller A L # Herendeen Bay Cold Bay N 0200KilometersW E S Prepared for The Nature Conservancy Juneau, Alaska by \•~.::--_\ Coastal & Oce.an Resources Inc~ COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES INC. 214-9865 W. Saanich Road, Sidney BC V8L 5Y8 Canada ph: 250.655.4035, web: www.coastalandoceans.com, email: [email protected] SUMMARY ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system in which georeferenced aerial imagery is collected specifically for the interpretation and integration of geological and biological features of the intertidal zone and nearshore environment. Oblique low-altitude aerial video and digital still imagery of the coastal zone is collected during summer low tides (zero tide level or lower), usually from a helicopter flying at <100 m altitude. The flight trackline is recorded at 1-second intervals using Fugawi electronic navigation software and is continuously monitored in-flight to ensure all shorelines have been imaged. Video and still imagery is georeferenced and time-synchronized. Video imagery is accompanied by continuous, simultaneous commentary by a geologist and a biologist aboard the aircraft. The imagery and commentary are later used in the definition of discrete along-shore coastal habitat units and the “mapping” of observed physical, geomorphic, sedimentary, and biological features in those units. -

Occurance, Abundance, and Habitat Use of Birds Along The

OCCURRENCE, ABUNDANCE, AND HABITAT USE OF BIRDS ALONG THE NORTHCENTRAL ALASKA PENINSULA, 1976-1980. Robert E. Gill, Jr.l, Margaret R. Petersenl, and Paul D. Jorgensen2 Running head: Gillet al., Alaska Peninsula Birds lu.s. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1011 E. Tudor Road, Anchorage, Alaska 99503 26150 Thorn Street, San Diego, California 92115 ABSTRACT Between spring 1976 and fall 1980 we studied the occurrence, abundance, and habitat use of birds over a 2000 km2 segment of the northcentral Alaska Peninsula. During this period observers were present 473 days and obtained records for all seasons. The avifauna was found to be predominantly a mixture of Panboreal (39%), North American (34%), and Aleutican (19%) species with the Aleutican group dominant in terms of numbers and biomass. A total of 125 species was recorded: 63% (79 of 125) were water associated. Forty-two species were confirmed breeding in the area and another 19 were suspected of breeding. The majority of species occurred as migrants; 11 were considered permanent residents and an additional 23 were winter residents. Our observations extended the known Alaska breeding distribution of American wigeon (Anas americana), black turnstone (Arenaria melanocephala), northern phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus), short-billed dowitcher (Limnodromus griseus), western sandpiper (~. mauri), dunlin (Calidris alpina), horned puffin (Fratercula corniculata), tufted puffin (Lunda cirrhata), and orange-crowned warbler (Vermivora celata). Our observations also extended the known postbreeding range or significantly changed the known status of bar-tailed godwit (Limosa 1apponica), whimbrel 1 (Numenius phaeopus), lesser yellowlegs (Tringa flavipes), long-billed dowitcher (Limnodromus scolopaceus), dunlin (£. alpina), marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus}, American robin (Turdus migratorius), yellow-rumped warbler (Dendroica coronata), and dark-eyed junco (Junco hyemalis). -

Bristol Bay Flight Log 2006

CORI Project: 2006-17 24 July 2006 FLIGHT REPORT ShoreZone Aerial Video Imaging (AVI) Survey Bristol Bay, Alaska, 19-23 June 2006 ShoreZone Aerial Video Imaging Survey ALASKA Bristol Bay, Alaska 19-23 June 2006 Shoreline Imaged (2,412 km) State of Alaska Dillingham Kvichak Togiak # Bay Bay King Salmon # Kulukak Nushagak Bay Bay Egegik Bay A Ugashik L BRISTOL BAY Bay U S N I Port N # E Heiden P A K S Port A Moller A L # Herendeen Bay Cold Bay N 0200KilometersW E S Prepared for The Nature Conservancy Juneau, Alaska by COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES INC. 214-9865 W. Saanich Road, Sidney BC V8L 5Y8 Canada ph: 250.655.4035, web: www.coastalandoceans.com, email: [email protected] SUMMARY ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system in which georeferenced aerial imagery is collected specifically for the interpretation and integration of geological and biological features of the intertidal zone and nearshore environment. Oblique low-altitude aerial video and digital still imagery of the coastal zone is collected during summer low tides (zero tide level or lower), usually from a helicopter flying at <100 m altitude. The flight trackline is recorded at 1-second intervals using Fugawi electronic navigation software and is continuously monitored in-flight to ensure all shorelines have been imaged. Video and still imagery is georeferenced and time-synchronized. Video imagery is accompanied by continuous, simultaneous commentary by a geologist and a biologist aboard the aircraft. The imagery and commentary are later used in the definition of discrete along-shore coastal habitat units and the “mapping” of observed physical, geomorphic, sedimentary, and biological features in those units.