Upwards of 20 Batteaus All in a Body Made a Fine Appearance Coming Down the River, and Must Be Very Mortifying to Those Motionless at a Little Distance”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wanderings Newsletter of the OUTDOORS CLUB INC

Wanderings newsletter of the OUTDOORS CLUB INC. http://www.outdoorsclubny.org ISSUE NUMBER 108 PUBLISHED TRI-ANNUALLY Jul-Oct 2014 The Outdoors Club is a non-profit 501(c) (3) volunteer-run organization open to all adults 18 and over which engages in hiking, biking, wilderness trekking, canoeing, mountaineering, snowshoeing and skiing, nature and educational city walking tours of varying difficulty. Individual participants are expected to engage in activities suitable to their ability, experience and physical condition. Leaders may refuse to take anyone who lacks ability or is not properly dressed or equipped. These precautions are for your safety, and the wellbeing of the group. Your participation is voluntary and at your own risk. Remember to bring lunch and water on all full day activities. Telephone the leader or Lenny if unsure what to wear or bring with you on an activity. Nonmembers pay one-day membership dues of $3. It is with sorrow that we say goodbye to Robert Kaye, the brother of Alan Kaye, who died in January. We have been able to keep the dues the same, and publish the Newsletter because of Robert’s benevolence to the Club. Robert wanted to make sure that the Club would continue after Alan’s death. Please join Bob Susser and Helen Yee on Saturday, October 18th, at the New York Botanical Gardens for a memorial walk in honor of Robert Kaye. CHECK THE MAILING LABEL ON YOUR SCHEDULE FOR EXPIRATION DATE! RENEWAL NOTICES WILL NO LONGER BE SENT. It takes 4-6 weeks to process your renewal. Some leaders will be asking members for proof of membership, so please carry your membership card or schedule on activities (the expiration date is on the top line of your mailing label). -

An Integrated Blend of U.S. Political and Social History

Preview Chapter 6 Inside! An integrated blend of U.S. political and social history Offering an integrated blend of political and social history, THE AMERICAN JOURNEY frames the history of the U.S. as an ongoing quest by the nation’s citizens to live up to American ideals and emphasizes how this process has become more inclusive over time. David Goldfield The new Fifth Edition includes: University of North Carolina—Charlotte ■ 24 new “From Then to Now” features Carl E. Abbott that show connections between recent Portland State University and past events Virginia DeJohn Anderson University of Colorado at Boulder ■ Updated chapter-opening “Personal Journey” Jo Ann E. Argersinger Southern Illinois University sections that include references to additional Peter H. Argersinger online content in MyHistoryLab Southern Illinois University William Barney ■ Significantly revised material in Chapter 5, University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill “Imperial Breakdown,” and Chapter 16, Robert Weir “Reconstruction” University of South Carolina Brief Contents 1. Worlds Apart 17. A New South: Economic Progress and Social Tradition, 1877–1900 2. Transplantation, 1600–1685 18. Industry, Immigrants, and Cities, 3. The Creation of New Worlds 1870–1900 4. Convergence and Conflict, 1660s–1763 19. Transforming the West, 1865–1890 5. Imperial Breakdown, 1763–1774 20. Politics and Government, 1877–1900 6. The War for Independence, 1774–1783 21. The Progressive Era, 1900–1917 7. The First Republic, 1776–1789 22. Creating an Empire, 1865–1917 8. A New Republic and the Rise of the Parties, 23. America and the Great War, 1914–1920 1789–1800 24. Toward a Modern America: The 1920s 9. -

Letter from Benjamin Lincoln to George Washington,” (1786)

“Letter from Benjamin Lincoln to George Washington,” (1786) Annotation: Historians once characterized the 1780s as the "critical period" in American history, when the new nation, saddled with an inadequate system of government, suffered crippling economic, political, and foreign policy problems that threatened its independence. Although it is possible to exaggerate the country's difficulties during the first years of independence, there can be no doubt that the country did face severe challenges. One problem was the threat of government bankruptcy. The nation owed $160 million in war debts and the Congress had no power to tax and the states rarely sent in more than half of Congress's requisitions. The national currency was worthless. To help pay the government's debt, several members of Congress proposed the imposition of a five percent duty on imports. But because the Articles of Confederation required unanimous approval of legislation, a single state, Rhode Island, was able to block the measure. The country also faced grave foreign policy problems. Spain closed the Mississippi River to American commerce in 1784 and secretly conspired with Westerners (including the famous frontiersman Daniel Boone) to acquire the area that would eventually become Kentucky and Tennessee. Britain retained military posts in the Northwest, in violation of the peace treaty ending the Revolution, and tried to persuade Vermont to become a Canadian province. The economy also posed serious problems. The Revolution had a disruptive impact especially on the South's economy. Planters lost about 60,000 slaves (including about 25,000 slaves in South Carolina and 5,000 in Georgia). -

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION

CALIFORNIA HISTORIC MILITARY BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES INVENTORY VOLUME II: THE HISTORY AND HISTORIC RESOURCES OF THE MILITARY IN CALIFORNIA, 1769-1989 by Stephen D. Mikesell Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Sacramento District 1325 J Street Sacramento, California Contract: DACA05-97-D-0013, Task 0001 FOSTER WHEELER ENVIRONMENTAL CORPORATION Prepared by: JRP JRP HISTORICAL CONSULTING SERVICES Davis, California 95616 March 2000 California llistoric Military Buildings and Stnictures Inventory, Volume II CONTENTS CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................... i FIGURES ....................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................. iv PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1-1 2.0 COLONIAL ERA (1769-1846) .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Spanish-Mexican Era Buildings Owned by the Military ............................................... 2-8 2.2 Conclusions .................................................................................................................. -

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Official Correspondence New

Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Official Correspondence New Hampshire Committee of Safety to General Stark State of New Hampshire, Saturday, July 19th, 1777. To Brigd Genl Jn° Stark,—You are hereby required to repair to Charlestown, N° 4, so as to be there by 24th—Thursday next, to meet and confer with persons appointed by the convention of the State of Vermont relative to the route of the Troops under your Command, their being supplied with Provisions, and future operations—and when the Troops are collected at N°- 4, you are to take the Command of them and march into the State of Vermont, and there act in conjunction with the Troops of that State, or any other of the States, or of the United States, or separately, as it shall appear Expedient to you for the protection of the People or the annoyance of the Enemy, and from time to time as occasion shall require, send Intelligence to the Genl Assembly or Committee of Safety, of your operations, and the manoeuvers of the Enemy. M. Weare. Records of the Council of Safety and Governor and Council of the State of Vermont to which are prefixed the Records of the General Conventions from July 1775 to December 1777 Eliakim Persons Walton ed., vol. 1 (Montpelier: Steam Press, 1873), p. 133. Primary Sources Battle of Bennington Official Correspondence Committee of Safety, Vermont State of New Hampshire, In Committee of Safety, Exeter, July 23d 1777. Hon. Artemas Ward— Sir— Orders issued the last week for one Quarter part of two thirds of the Regiments of militia in this State to march immediately to the assistance of our Friends in the new State of Vermont, under the command of Br. -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

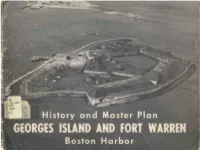

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

Continental Army: Valley Forge Encampment

REFERENCES HISTORICAL REGISTRY OF OFFICERS OF THE CONTINENTAL ARMY T.B. HEITMAN CONTINENTAL ARMY R. WRIGHT BIRTHPLACE OF AN ARMY J.B. TRUSSELL SINEWS OF INDEPENDENCE CHARLES LESSER THESIS OF OFFICER ATTRITION J. SCHNARENBERG ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION M. BOATNER PHILADELPHIA CAMPAIGN D. MARTIN AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE DELAWARE VALLEY E. GIFFORD VALLEY FORGE J.W. JACKSON PENNSYLVANIA LINE J.B. TRUSSELL GEORGE WASHINGTON WAR ROBERT LECKIE ENCYLOPEDIA OF CONTINENTAL F.A. BERG ARMY UNITS VALLEY FORGE PARK MICROFILM Continental Army at Valley Forge GEN GEORGE WASHINGTON Division: FIRST DIVISION MG CHARLES LEE SECOND DIVISION MG THOMAS MIFFLIN THIRD DIVISION MG MARQUES DE LAFAYETTE FOURTH DIVISION MG BARON DEKALB FIFTH DIVISION MG LORD STIRLING ARTILLERY BG HENRY KNOX CAVALRY BG CASIMIR PULASKI NJ BRIGADE BG WILLIAM MAXWELL Divisions were loosly organized during the encampment. Reorganization in May and JUNE set these Divisions as shown. KNOX'S ARTILLERY arrived Valley Forge JAN 1778 CAVALRY arrived Valley Forge DEC 1777 and left the same month. NJ BRIGADE departed Valley Forge in MAY and rejoined LEE'S FIRST DIVISION at MONMOUTH. Previous Division Commanders were; MG NATHANIEL GREENE, MG JOHN SULLIVAN, MG ALEXANDER MCDOUGEL MONTHLY STRENGTH REPORTS ALTERATIONS Month Fit For Duty Assigned Died Desert Disch Enlist DEC 12501 14892 88 129 25 74 JAN 7950 18197 0 0 0 0 FEB 6264 19264 209 147 925 240 MAR 5642 18268 399 181 261 193 APR 10826 19055 384 188 116 1279 MAY 13321 21802 374 227 170 1004 JUN 13751 22309 220 96 112 924 Totals: 70255 133787 1674 968 1609 3714 Ref: C.M. -

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875)

Principal Fortifications of the United States (1870–1875) uring the late 18th century and through much of the 19th century, army forts were constructed throughout the United States to defend the growing nation from a variety of threats, both perceived and real. Seventeen of these sites are depicted in a collection painted especially for Dthe U.S. Capitol by Seth Eastman. Born in 1808 in Brunswick, Maine, Eastman found expression for his artistic skills in a military career. After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where offi cers-in-training were taught basic drawing and drafting techniques, Eastman was posted to forts in Wisconsin and Minnesota before returning to West Point as assistant teacher of drawing. Eastman also established himself as an accomplished landscape painter, and between 1836 and 1840, 17 of his oils were exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York City. His election as an honorary member of the academy in 1838 further enhanced his status as an artist. Transferred to posts in Florida, Minnesota, and Texas in the 1840s, Eastman became interested in the Native Americans of these regions and made numerous sketches of the people and their customs. This experience prepared him for his next five years in Washington, D.C., where he was assigned to the commissioner of Indian Affairs and illus trated Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s important six-volume Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. During this time Eastman also assisted Captain Montgomery C. Meigs, superintendent of the Capitol Brevet Brigadier General Seth Eastman. -

FISHKILLISHKILL Mmilitaryilitary Ssupplyupply Hubhub Ooff Thethe Aamericanmerican Rrevolutionevolution

Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 1234 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, fi ndings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Department of the Interior. FFISHKILLISHKILL MMilitaryilitary SSupplyupply HHubub ooff tthehe AAmericanmerican RRevolutionevolution 11776-1783776-1783 “...the principal depot of Washington’s army, where there are magazines, hospitals, workshops, etc., which form a town of themselves...” -Thomas Anburey 1778 Friends of the Fishkill Supply Depot A Historical Overview www.fi shkillsupplydepot.org Cover Image: Spencer Collection, New York Public Library. Designed and Written by Hunter Research, Inc., 2016 “View from Fishkill looking to West Point.” Funded by the American Battlefi eld Protection Program Th e New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1820. Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 5678 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 Fishkill Military Supply Hub of the American Revolution In 1777, the British hatched a scheme to capture not only Fishkill but the vital Fishkill Hudson Valley, which, if successful, would sever New England from the Mid- Atlantic and paralyze the American cause. The main invasion force, under Gen- eral John Burgoyne, would push south down the Lake Champlain corridor from Distribution Hub on the Hudson Canada while General Howe’s troops in New York advanced up the Hudson. In a series of missteps, Burgoyne overestimated the progress his army could make On July 9, 1776, New York’s Provincial Congress met at White Plains creating through the forests of northern New York, and Howe deliberately embarked the State of New York and accepting the Declaration of Independence. -

CHAINING the HUDSON the Fight for the River in the American Revolution

CHAINING THE HUDSON The fight for the river in the American Revolution COLN DI Chaining the Hudson Relic of the Great Chain, 1863. Look back into History & you 11 find the Newe improvers in the art of War has allways had the advantage of their Enemys. —Captain Daniel Joy to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, January 16, 1776 Preserve the Materials necessary to a particular and clear History of the American Revolution. They will yield uncommon Entertainment to the inquisitive and curious, and at the same time afford the most useful! and important Lessons not only to our own posterity, but to all succeeding Generations. Governor John Hancock to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, September 28, 1781. Chaining the Hudson The Fight for the River in the American Revolution LINCOLN DIAMANT Fordham University Press New York Copyright © 2004 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ii retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotation: printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Diamant, Lincoln. Chaining the Hudson : the fight for the river in the American Revolution / Lincoln Diamant.—Fordham University Press ed. p. cm. Originally published: New York : Carol Pub. Group, 1994. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 (pbk.) 1. New York (State)—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 2. United States—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 3. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. -

George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries 3A, Varick Transcripts, Letterbook 6

George Washington Papers, Series 3, Subseries 3A, Varick Transcripts, Letterbook 6 To THE PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS Head Quarters, New Windsor, March 1, 1781. Sir: The inclosed memorial of Colo. Hazen was this day put into my hands. Many of the matters mentioned in it are better known to Congress than to myself. The whole are so fully stated, as to speak for themselves, and require only the determination of Congress. The case of the Canadian Officers and Soldiers I know to be peculiarly distressing and truly entitled to redress, if the means are to be obtained. The Regiment, not being appropriated to any State, must soon dwindle into nothing, unless some effectual mode can be devised for recruiting it. Colo. Hazens pretensions to promotion seems to me to have weight, but how far they ought to be admitted, the general principles which Congress mean to adopt for the regulation of this important point will best decide. In justice to Colo. Hazen, I must testify, that he has always appeared to me a sensible, 83 spirited and attentive Officer. I have the honor etc. To THE PRESIDENT OF CONGRESS Head Quarters, New Windsor, March 1, 1781. Sir: On opening the inclosed, I found it intended for 83. In the writing of Tench Tilghman. The letter was read in Congress on March 23 and referred to Artemas Ward, John Sullivan, and Isaac Motte. your Excellency, though addressed to me. I intend setting out in the morning for Newport to confer with the French General and Admiral upon the operations of the ensuing Campaign.