Dallas, November 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness Hero 3

Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center’s Wilderness Investigations High School Wilderness Hero #3 John F. Kennedy President John F. Kennedy; 35th U.S. President (No copyright indicated) Common Core Standard Connections Standards addressed will vary depending on how the teacher chooses to approach the lesson and/or activities. Instructions for the teacher: Rarely, if ever, is one individual responsible for the hard work and vision involved in bringing about wilderness legislation, specific wilderness designation, or wilderness management. The 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, was an important player in the ultimate success of the Wilderness Act of 1964 (signed into law the year after his untimely death). John F. Kennedy is the focus of this Wilderness Hero spotlight. To help students get to know this amazing wilderness hero, choose one or more of the following: • Photocopy and hand out Wilderness Hero Sheet #3 to each student. 143 o Based on the information found there, have them write a short news article about John F. Kennedy and his role in the story of designated wilderness. • From the list of wilderness quotes found within Wilderness Hero Sheet #3, have students select one or more, copy the quote, and then interpret what the quote(s) means to them. • Use the handout as the basis of a short mini-lesson about John F. Kennedy and wilderness. • Have students research John F. Kennedy’s presidency and from their findings create a timeline showing important events taking place during President Kennedy’s administration (January 1961 – November 1963). o This was a time of significant national and world events (Cuban Missile Crisis, civil rights movement, early Viet Nam War involvement, financial challenges, etc.). -

John F. Kennedy and West Virginia, 1960-1963 Anthony W

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2004 John F. Kennedy and West Virginia, 1960-1963 Anthony W. Ponton Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Election Law Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, Politics Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ponton, Anthony W., "John F. Kennedy and West Virginia, 1960-1963" (2004). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 789. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John F. Kennedy and West Virginia, 1960-1963. Thesis Submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts, Department of History by Anthony W. Ponton Dr. Frank Riddel, Committee Chairperson Dr. Robert Sawrey Dr. Paul Lutz Marshall University April 27, 2004 Abstract John F. Kennedy and West Virginia, 1960-1963 By Anthony W. Ponton In 1960, John F. Kennedy, a wealthy New England Catholic, traveled to a rural, Protestant state to contend in an election that few thought he could win. While many scholars have examined the impact of Kennedy’s victory in the West Virginia primary, few have analyzed the importance that his visit to the state in 1960 and his ensuing administration had on West Virginia. Kennedy enacted a number of policies directed specifically toward relieving the poverty that had plagued West Virginia since statehood. -

BANK DEBITS T 16,19Ft and DEPOSIT TURNOVER

statist i(o release For immediate release BANK DEBITS T 16,19ft AND DEPOSIT TURNOVER Bank debits to demand deposit accounts, except interbank and U. S. Government accounts, as reported by "banks in 3^4 selected centers for the month of November aggregated $333*9 billion. During the past three months debits amounted to $1,026.4 billion or 8.7 per cent above the total reported for the corresponding period a year ago. At banks in New York City there was an increase of 10.6 per cent compared with the corresponding three-months period a year ago; at 6 other leading centers the increase was 4.3 per cent; and at 337 other centers it was 9.1 per cent. Seasonally adjusted debits to demand deposit accounts increased further in November to a level of $352.0 billion, but still remained slightly below the July peak. Changes at banks in New York City and 6 other leading centers were small and partially offsetting, but at 337 other centers, debits reached a new peak of $135-4 billion. The seasonally adjusted annual rate of turnover of demand deposits at 3^3 centers outside New York City remained unchanged at 35*5, a little below the April high but about 3-5 per cent higher than the October-November average last year. Total, Leading centers 337 Total, Leading centers 337 343 Period 344 other 344 other centers centers NYC 6 others * centers NYC 6 others* centers DEBITS To Demand Deposit Accounts ANNUAL RATE OF TURNOVER (In billions of dollars) Of Demand Deposits Not seasonally adjusted - November 296.6 116.7 63.8 116.1 43.6 8o.4 45.3 29.4 33-6 December -

An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Christina Paige Jones East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2001 The ndE of Camelot: An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Christina Paige Jones East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Christina Paige, "The ndE of Camelot: An Examination of the Presidency of John F. Kennedy in 1963." (2001). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 114. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/114 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE END OF CAMELOT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN F. KENNEDY IN 1963 _______________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History _______________ by Christina Paige Jones May 2001 _______________ Dr. Elwood Watson, Chair Dr. Stephen Fritz Dr. Dale Schmitt Keywords: John F. Kennedy, Civil Rights, Vietnam War ABSTRACT THE END OF CAMELOT: AN EXAMINATION OF THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN F. KENNEDY IN 1963 by Christina Paige Jones This thesis addresses events and issues that occurred in 1963, how President Kennedy responded to them, and what followed after Kennedy’s assassination. This thesis was created by using books published about Kennedy, articles from magazines, documents, telegrams, speeches, and Internet sources. -

22 November 1963: Where Were You?

22 November 1963: Where Were You? Our Class had a unique relationship with President John F. Kennedy. He became president when we became upper class. He was a Navy Man, war hero, skipper of PT- 109. He loved football and the Army-Navy game. We lost our ‘rubbers’ when we marched in his Inaugural Parade, and we lost our innocence on 22 November 1963. Our experiences that day were unique, and for the first time since throwing our hats in Halsey Field House five months earlier, we were all unified via a single event. What is your story? Where were you when you first heard that the President had been assassinated? Our classmates contributed the following memories. Ron Walters (6th Co): I remember that day. I was on the USS Cromwell (DE- 1014) off the coast of Brazil when President Kennedy was assassinated. Mike Blackledge (4th Co): I had just returned from [grad school] math class at North Carolina State and as I came through the quadrangle, I heard the radios reporting from the open windows of the dormitories. I received a second shock when one of the undergrads called out, “Hey, I wonder what Jackie’s doing tonight?” Two different worlds. Bob Lagassa (2nd Co): I will never forget that day. I, along with a large group of '63 classmates, was in the middle of a typical Submarine School day of study and lectures at SubBase New London when we heard the fateful news. We were stunned, shocked, angry, tearful! Classes were suspended the remainder of the day and we went to our loved ones for consolation. -

Education Programs

VIRTUAL EDUCATION PROGRAMS Virtual Tours Beginning January 2021 Visit The Sixth Floor Museum’s permanent exhibit, John F. Kennedy and the Memory of a Nation, from your own classroom. Explore key issues during the early 1960s and determine how they impacted President Kennedy’s time in office. Follow the events of President Kennedy’s trip to Texas in November 1963 through primary sources, photographs, and documents leading up to the assassination and the resulting investigation. Live Tour Recorded Tour Available Mondays at 10 a.m. $75 | 30 minutes $100 | 50–60 minutes 4th–12th grades 4th–12th grades | ≤60 students Distance Learning Virtual Offerings | Distance Learning Live NEW! Debating the Issues $100 | 50 minutes | 9th–12th grades | ≤60 students President Kennedy encouraged citizens of all ages to be actively involved in their communities and participate in civic discourse. Students will take on issues of the 1960s, examining their connections to current events before engaging in mini–debates. Courtesy the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston NEW! Civics in My Time $100 | 50 minutes | 6th–8th grades | ≤60 students How can you make a difference in your community if you are not old enough to vote? Students will learn about the three branches of government and how citizens can influence government decisions through civic engagement. Students will learn how to debate issues that will ultimately impact their own communities. Jesse Moyers Collection / The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza Virtual Education Programs | 2020–2021 Page 1 of 4 UPDATED Resistance: Civil Rights and Kennedy’s Legacy $100 | 50 minutes | 6th–8th grades and 9th–12th grades | ≤60 students In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement was a major focus of change in the United States. -

The Money Market in November 1963

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF NEW YORK 179 The Money Market in November The entire financial community shared the shock of the the hacking, not only of the actual foreign currency hold- nation over the assassination of President Kennedy on the ings of the United States, but also of the nearly $2 billion afternoon of Friday, November22, but an emotional back- of foreign currencies available under the Federal Reserv&s lash on financial values that could have had disturbing network of swap arrangements with foreign central banks. consequences for the economy was largely avoided. In an Before the end of Friday, joint plans of action for Satur- atmosphere of great uncertainty, the stock exchanges sus- day and Monday were worked out in telephone contacts pended trading shortly after 2 p.m., Friday. The Govern- with foreign central banks. With foreign exchange markets ment securities market, where trading had come toa stand- abroad open on Saturday and Monday. operations by still upon receipt of the news, also closed early, as did foreign central banks in their respective markets re- other securities markets. Over the week end and the day inforced the New York Federal Reserve Bank's interven- of national mourning on Monday, November 25, the pub- tion on Friday afternoon in New York. As a result, lic had ample opportunity to reflecton the orderly transfer foreign exchange markets remained orderly and specula- of authority to the new President and on President John- tive movements were held to a minimum. The speed of son's assurances that the nation's purposes and policies action and the stability of the markets once again dem- would remain unchanged. -

Lyndon B. Johnson, "Let Us Continue" (27 November 1963)

Voices of Democracy 4 (2009): 97‐119 Barrett 97 LYNDON B. JOHNSON, "LET US CONTINUE" (27 NOVEMBER 1963) Ashley Barrett Baylor University Abstract "Let Us Continue" was one of the most important speeches of Lyndon Johnson's political career; it served as a gateway to the leadership and legitimacy he needed for his presidency to succeed. This essay investigates the composition of "Let Us Continue" and seeks to rightfully accredit Horace Busby as the most important speechwriter to contribute to its artistry and success. The essay also emphasizes the obstacles Johnson confronted in his ascension to the Oval Office. Key Words: Lyndon Baines Johnson, John F. Kennedy, Theodore Sorensen, Horace Busby, presidential assassination, and speechwriting. All I have I would have given gladly not to be standing here today. The greatest leader of our time has been struck down by the foulest deed of our time. Today John Fitzgerald Kennedy lives on in the immortal words and works that he left behind. He lives on in the minds and memories of mankind. He lives on in the hearts of his countrymen. No words are sad enough to express our sense of loss. (2‐7)1 Lyndon Baines Johnson November 27, 1963 The assassination of President John F. Kennedy represented a period of national mourning for the young leader's tragic loss. Although the "president's ratings in the polls were as low as they had ever been," Americans struggled to process the tragedy and feared the threat to their national security.2 No one realized these threats better than Lyndon B. -

Docid-32389028.Pdf

This document is made available through the declassification efforts and research of John Greenewald, Jr., creator of: The Black Vault The Black Vault is the largest online Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) document clearinghouse in the world. The research efforts here are responsible for the declassification of hundreds of thousands of pages released by the U.S. Government & Military. Discover the Truth at: http://www.theblackvault.com T · - ---- · --~ ·- -- - l Date: 01/18/05 JFK ASSASSINATION SYSTEM IDENTIFICATION FORM ------------------------------------- - ------------~~--~~~--~~~~ AGENCY INFORMATION ~eleased under the John f. Kennedy AGENCY CIA ~ssassination Records RECORD NUMBER 104-10400-10000 ollection Act of 1992 RECORD SERIES JFK (44 USC 2107 Note) . AGENCY FILE NUMBER RUSS HOLMES WORK FILE rase# :NW 533 20 Date: d6-24-2017 DOCUMENT INFORMATION AGENCY ORIGINATOR CIA FROM TO TITLE INVENTORY: ANCILLARY FILES (RUSS HOLMES WORK FILESi DATE 10/22/1964 PAGES 31 SUBJECTS INVENTORY JFK ASSASSINATION DOCUMENT TYPE PAPER CLASSIFICATION SECRET RESTRICTIONS 1B CURRENT STATUS RELEASED IN PART PUBLIC - RELEASED WITH DELETIONS DATE OF LAST REVIEW 07/07/04 COMMENTS JFK-RH01 : FINVENTORY-1 20040323-1063435 [R] - ITEM IS RESTRICTED 104-10400-10000 NW 53320 Docld:32389028 Page 1 / s T .B.hx - Np~. · 01 (Inventory): · ANCILLARY FILES Primarily Based upon or Related to Subjects in LEE HARVEY OSWALD's 201-28924~ * * * * * 001~ Robert S. ALLEN & Paul SCOTT. "Secret Report under Wraps", Northern Virginia Sun, 22 October 1964. - ALLEN & SCOTT allege that CIA withheld from the Warren Commission significant information on Soviet State Security organization and capability to perform assassinations abroad. 002. Bella ABZUG's Subcommittee on Government Operation : Request regarding Warren Commission Document [late 1975]. -

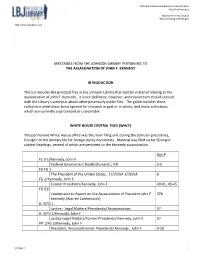

Materials from the Johnson Library Pertaining to the Assassination of John F

National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org MATERIALS FROM THE JOHNSON LIBRARY PERTAINING TO THE ASSASSINATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF) This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, several of which are pertinent to the Kennedy assassination. Box # FE 3-1/Kennedy, John F. Federal Government Deaths/Funerals, JFK 3-5 EX FG 1 The President of the United States, 11/22/64-1/10/64 9 FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Former Presidents/Kennedy, John F. 40-41, 43-45 FG 635 Commission to Report on the Assassination of President John F. 376 Kennedy (Warren Commission) JL 3/FG 1 Justice - Legal Matters/Presidential Assassinations 37 JL 3/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Justice Legal Matters/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 37 PP 1/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. President, Personal/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 9-10 02/28/17 1 National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org (Cross references and letters from the general public regarding the assassination.) PR 4-1 Public Relations - Support after the Death of John F. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

KEg/ifilCIED GENERAL AGREEMENT ON L/19^7 13 December 1962 TARIFFS AND TRADE Limited Distribution NEWLY INDEPENDENT STATES Status under Recommendations of 18 November i960, 9 December 196l and 14 November 1962 By the Recommendation of 18 November i960 (9S/l6) contracting parties are recommended to continue for a period of two years to apply the GATT, on a de facto basis and subject to reciprocity, in their relations with territories which acquire full autonomy in the conduct of their external commercial relations and of other matters provided for in the General Agreement but which require some time to consider their future commercial policy and the question of their relations with the GATT. Under the Recommendation of 9 December 1961 (lOS/17), this de facto application is to be extended for a further year in respect of States which request this longer period in which to decide upon their future relations with the GATT. For certain States in Africa, the period was again extended, by the Decision of 14 November 1962 (L/1934), until the close of the last ordinary session of the CONTRACTING PARTIES in 1963.I The following is the situation in respect of the States to which the Recommendations are at present applicable: Expiry date under Extended expiry date Recommendation of I960 under Recommendation (2 years after date of of 1961 or 1962 independence) Algeria 3 July 1964 Burundi 1 July 1964 •Cameroun 1 January 1962 15 November 1963 •Central African Republic 14 August 1962 15 November 1963 *Chad 11 August 1962 15 November 1963 •Congo (Brazzaville) -

Foreign & Domestic Policy of the 1960S: John F. Kennedy & Lyndon

Name ____________________ APUSH Unit 13, #2 Date ____________ Pd _____ Foreign & Domestic Policy of the 1960s: John F. Kennedy & Lyndon B. Johnson I. John F. Kennedy & the New Frontier A. The 1960 election between Nixon & Kennedy was one of the closest in history & was 1st to use TV debates B. JFK’s “New Frontier” domestic agenda 1. Promised a return to FDR-era liberal social reforms 2. Most social reforms, like education and health care, were blocked by Congress 3. The economy was stimulated by new jobs due to industry, government spending, & tax cuts 4. JFK & the “New Frontiersmen” strengthened the power of the president & executive staff C. Kennedy intensified the Cold War 1. Contain communism, close the missile gap, & increase U.S. defenses were JFK’s 1st priories 2. JFK shifted from Eisenhower’s “brinksmanship” to a “flexible response” & “first strike” policy 3. Fighting Communism: a. The Peace Corps and Alliance for Progress helped underdeveloped nations b. Committed the USA to winning the space race by beating the USSR to the moon (the USA did it in 1969) c. The Berlin crisis led to the Berlin Wall in 1961 d. JFK committed the U.S. to Vietnam after South Vietnam’s leader, Ngo Dihn Diem, was killed in 1963 e. JFK failed to overthrow Castro in Cuba during the CIA-led Bay of Pigs invasion f. The Cuban Missile Crisis brought the U.S. & Soviet Union to near nuclear war i. The U.S. successfully quarantined Cuba & forced a Soviet withdrawal of nuclear missiles ii. The Cuban Missile Crisis led to better U.S./Soviet communication & more negotiation II.