Klipsun Magazine, 2001, Volume 31, Issue 04-April

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Surfing, Gender and Politics: Identity and Society in the History of South African Surfing Culture in the Twentieth-Century

Surfing, gender and politics: Identity and society in the history of South African surfing culture in the twentieth-century. by Glen Thompson Dissertation presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Albert M. Grundlingh Co-supervisor: Prof. Sandra S. Swart Marc 2015 0 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the author thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 8 October 2014 Copyright © 2015 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study is a socio-cultural history of the sport of surfing from 1959 to the 2000s in South Africa. It critically engages with the “South African Surfing History Archive”, collected in the course of research, by focusing on two inter-related themes in contributing to a critical sports historiography in southern Africa. The first is how surfing in South Africa has come to be considered a white, male sport. The second is whether surfing is political. In addressing these topics the study considers the double whiteness of the Californian influences that shaped local surfing culture at “whites only” beaches during apartheid. The racialised nature of the sport can be found in the emergence of an amateur national surfing association in the mid-1960s and consolidated during the professionalisation of the sport in the mid-1970s. -

Wets Lose in House by Vote of 227-187

;• • - - / . r :•* A V k B A C ® D AILT CnOOLAIION far the MoBth of FM rvaiy, IMS • r C r K W tim m B m m Hmitfoei ^ 5 , 5 3 5 fU r ^ odder tealgM; Jtoeedey Btanber of AnOt Boreaii iiatttb p fitfr fd r and conttnoed cold; tkiag tern* of dreolBtloii. pei'ature.. WodDeedigr« VOL. U ., NO. 140. (CteMlfled Adverttdng on Pace 10.), SOUTH MANCHfiSTEIL CONN., MONDAY, MARCH 14, 1932. (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS HINDENBURG WINS; Off on Canoe Trip From Washingrton to Mexico .V V • WETS LOSE IN HOUSE X v-r-x -X vix W jv.v-: A MUST RUN AGAIN '—V ’/»} ..... --------------------- ^ ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 'yy BY VOTE OF 227-187 Akhongh Seven IHiHion Votes ■ (XUK GALORE- First Vote Oo ProhibitioD Re Eastman Kills Self; NORESDITSIN vision Held In Twelve Hy-IsCerlainofElecfion^ LINDBERGH CASE Noted Camera Maker Years Puts Members On Rochester, N. Y., March 14— (AP)— George Eastman, 77, Record For Or Against; Berlin, March 14.—(AP) —Presi From Many Parts of Nation millionaire manufacturer, phil Philanthropist dent Paul von Hindenburg, who anthropist and big game hunt Wet Vote Larger Tban missed re-election yesterday by Come Stories of Infant er, shot himself to death today 169,752 votes although he ran near in his East Avenue home here. Many of Tbem Expected. ly 7,500.000 ahead of Adolf Hitler, Dr. Audley D. Stewa(rt, an consented today to run again on the Being Seen Bot They All nouncing that Eastnlan had second ballot, April 10, and his elec shot himself after putting all Washington, March 14.—(AP) — tion was regarded as a certainty. -

1 in SEARCH of CAPTAIN ZERO Screenplay by Allan Weisbecker

1 IN SEARCH OF CAPTAIN ZERO Screenplay by Allan Weisbecker Based on his book November 1, 2003 2 BLACKNESS, THE VOID The fast lub-dub of a heartbeat… the whoosh of a planing surfboard… and now the voice of Alex… ALEX (V.O.) I need to tell you about that wave… A FANTASTIC EXPLOSION OF SWIRLING LIQUID ENERGY Becoming a figure of a man as seen through the back of wall of a wave, all emerald and abstract, the man zooming by as the wave tunnels over him and -- strangely, because there is danger here and the man should be fearful -- the heartbeat is… slowing… ALEX (V.O.)(CONT’D) …that… moment I had… inside that wave… INSIDE THE WAVE The heartbeat slows further… the shimmering blue-green cavern expanding… the man so deep inside… that space yet growing… immense… the man deeper still… ALEX’S MOMENT This is a moment out of time… a moment wherein there is no danger, no fear, because the future is an illusion… and being inside that moment and inside the miracle of a wave… This is the most beautiful thing in the world. And that swirling liquid beauty slowly becomes… the blackness of the void again… silence… …the heartbeat stops… Alex’s voice now, so clear, calm, serene… so deep within himself… ALEX (V.O.)(CONT’D) I’m… there… right now… in that moment… because… that moment… is… forever. Hold on the quiet and the blackness, then, the sound of hammering jars us and we… SMASH CUT TO 3 EXT. SUBURBIA – DAY Malls, Burger Kings, traffic. -

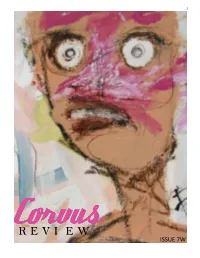

R E V I E W Issue 7W 2

1 R E V I E W ISSUE 7W 2 This issue of Corvus Review is dedicated to: Margaret “Marg” Josephine Pittman Feb 22, 1922-Feb. 13, 2017 EDITORS: Janine “Typing Tyrant” Mercer, EIC Luciana Fitzgerald, Fiction Editor COVER ART: C.F. Roberts Writer/Artist/Videographer/Provocateur/High -Functioning Autistic/Former Zine Publisher. Blog: http://cfrobertsuselessfilth.blogspot.com/ Art: http://cfrobertsuselessfilth.blogspot.com/ 3 4. R.Q. Flanagan 5. N. Sumislaski 6. T.L. Naught 8. A. Tipa 9. J. Riccio 11. D. Fagan 12. S.A. Ortiz 13. A. Cole 14. R.G. Foster 15. L. Suchenski 16. D. Tuvell 17. M. L. Johnson 18. S. Laudati 19. R. Nisbet 20. R. Hartwell N.F. 57. M.D. Laing 92. C. Valentza 23. M. Watson N.F. 62. S. Roberts 93. D.D. Vitucci 27. T. Smith N.F. 63. J. Hunter 96. J. Hickey 28. G. Vachon N.F. 67. N. Kovacs 99. J. Bradley 31. K. Shields 69. T. Rutkowski 100. S.F. Greenstein 32. J. Half-Pillow 70. B. Diamond 104. J. Mulhern 37. M. Wren 72. F. Miller 109. B.A. Varghese 38. D. Clark 79. K. Casey 113. K. Maruyama 39. P. Kauffmann 80. K. Hanson 119. K. Azhar 42. Z. Smith 82. J. Butler 120. Author Bio’s 44. J. Hill 83. R. Massoud 46. J. Gorman 86. M. Lee 51. B. Taylor 88. J. Rank 56. M.A. Ferro 4 On Taking a Complete Stranger to the Gynecologist Ryan Quinn Flanagan I have allergies and I have glow sticks and I have driven a complete stranger to the gynecologist, wondering about the sanitary nature of my passenger seat the whole time, playing it cool like Clint Eastwood with a cannon in my pants but soon feeling bad for the girl abandoned by family -

Protesters Crash AS Open House

FRIDAY', APRII 19, NV \\ \\ IIIESPARTANDAILY.COM iWuERE's Mv LicHTER? Karla Gachet uses surfing as a metaphor for life. Opinion, 2 ELITE STATUS Spartan women's rugby team heads off to national competition in Iowa. the VoL. 118 Ling Sports, 4 sfer "pp No. 54 V ALSO IN TODAY'S ISSUE r of ved Opinion 2 Sparta Guide 3 Letters 2 c T c Sports 6 Crossword 5 Classified 5 een ARVING ,,AN JOSE 3TATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 ras in ad nd- Players eld t of Protesters it's try wait for NFL crash A.S. draft open house results Supporters, protesters clash about the way funds By Dray Miller were obtained to renovate the University House DAIL\ SI \ FI WNW R College football players from around the country face a hectic By Alvin M. Morgan and stressful two days this week- DARN' SIAII WRITI R end, as they sit and wait to find San Jose State University out when and by what teams President Robert Caret they are selected in the NFL's addressed a crowd consisting 2002 college draft. of administration, staff, facul- For some players, including a ty and members of student few at San Jose State University, goveriunent Thursday during the stress lies in whether or not the ribbon-cutting ceremony they will even be selected. for the newly renovated Uni- The question for some players, versity House. such as highly touted University "When I walked on this of Oregon quarterback Joey Har- campus seven years ago, I did- rington, is not if they'll be drafted, n't think there was anything but when, while others d- face the that could be done to save this reality of not being drafted at all. -

WINTER 2008 • Volume 16, Issue 3

1 President’s Perspective Dear Florida Tech Alumni and Friends, It’s spring on the Florida Tech campus and the new semester is in full swing. We hope we’ve captured some of the excitement of these times in Florida Tech TODAY as well as provided a look at past accomplishments and new plans and priorities. First, in January, we went to the next level in TODAY the 50th Anniversary Campaign for Florida Tech with an exceptionally generous gift from the Harris Corp. Charitable Fund. Florida Institute of Technology PRESIDENT Anthony James Catanese, Ph.D., FAICP The gift means a new institute for the College of Engineering and a new SR. VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADvaNCEMENT Thomas G. Fox, Ph.D. building for that college and the College of Science. Florida Tech TODAY is published three times a year Also in this issue, we look at what a busy anniversary year this is for still by Florida Tech’s Office for Advancement and is more campus construction. New residence halls will be completed, a new distributed to over 50,000 readers. aviation center takes shape and other new structures, including an autism MANAGING EDITOR/DESIGNER Judi Tintera, [email protected] EDITOR Jay Wilson, [email protected] research and treatment center, begin to become realities. ASSISTANT EDITOR Karen Rhine, [email protected] What have our students and faculty recently COPY EDITOR Christena Callahan, [email protected] CLASS NOTES REPORTER Verna Layman, [email protected] accomplished? You’ll read in these pages that our CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Joan Bixby, Christena Callahan, Panther cadets are #1 in the region, that the biggest Diane Deaton, Ken Droscher, Brian Ehrlich, Joshua Flanagan, Melinda Millsap, Karen Rhine, Jay Wilson research telescope in Florida was installed and how a faculty member is a discoverer of a new planet. -

Nick Waterhouse

Het blad van/voor muziekliefhebbers 8 juni 2012 nr. 288 No Risk Disc: NICK WATERHOUSE www.platomania.nl • www.sounds-venlo.nl • www.kroese-online.nl • www.velvetmusic.nl • www.waterput.nl • www.de-drvkkery.nl adv_umg_plato mania_3fm_fc_©OCHEDA 16-05-12 14:03 Pagina 1 mANIA 288 VOOR DE ECHTE N RISK MUZIEKLIEFHEBBER! DISCNIET GOED GELD TERUG NICK WATERHOUSE Time’s All Gone (V2) Time’s All Gone is het sprankelende en soulvolle debuutalbum van Nick Waterhouse. Hij maakt r&b in de beste jaren vijftig traditie met hedendaagse WILL AND THE PEOPLE LION IN THE MORNING SUN 01 GOTYE SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW (FEATURING KIMBRA) OF MONSTERS AND MEN LITTLE TALKS 02 BEN HOWARD KEEP YOUR HEAD UP invloeden. Vette blazers (oudgediende Ira Raibon op YOUNG THE GIANT MY BODY 03 TRIGGERFINGER I FOLLOW RIVERS (LIVE@GIEL) baritonsax), koortjes (The Naturelles), analoge sound. THE ROOTS & CODY CHESTNUTT THE SEED (2.0) 04 EMELI SANDE NEXT TO ME (ACOUSTIC VERSION) GO BACK TO THE ZOO SMOKING ON THE BALCONY 05 JAMIE WOON NIGHT AIR De 25-jarige, uit Californië afkomstige zanger is het best TWO DOOR CINEMA CLUB UNDERCOVER MARTYN 06 LANA DEL REY VIDEO GAMES te scharen in het rijtje Sharon Jones, Mark Ronson, Amy SIA CLAP YOUR HANDS 07 EMMA LOUISE JUNGLE HUNGRY KIDS OF HUNGARY SCATTERED DIAMONDS 08 KEANE SILENCED BY THE NIGHT Winehouse en Stones Throw-labelgenoot Aloe Blacc. ALEX CLARE TOO CLOSE 09 AGNES OBEL JUST SO De sound ligt soms heerlijk dichtbij de iets rauwere CRYSTAL FIGHTERS PLAGE 10 FINK YESTERDAY WAS HARD ON ALL OF US WILLY MOON I WANNA BE YOUR MAN 11 THE KOOKS IS IT ME rockabilly, zowel door zijn stem als door de van tijd THE ASTEROIDS GALAXY TOUR HEART ATTACK 12 FLORENCE + THE MACHINE SHAKE IT OUT tot tijd scheurende gitaar van Waterhouse. -

Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 62 (July 2015)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 62, July 2015 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, July 2015 SCIENCE FICTION Crazy Rhythm Carrie Vaughn Life on the Moon Tony Daniel The Consciousness Problem Mary Robinette Kowal Violation of the TrueNet Security Act Taiyo Fujii FANTASY Adventures in the Ghost Trade Liz Williams Saltwater Railroad Andrea Hairston Ana’s Tag William Alexander NOVELLA Dapple Eleanor Arnason NOVEL EXCERPTS Wylding Hall Elizabeth Hand Dark Orbit Carolyn Ives Gilman NONFICTION Interview: Kelly Link The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy Book Reviews Andrew Liptak Artist Gallery Euclase Artist Spotlight: Euclase Henry Lien AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Carrie Vaughn Tony Daniel Mary Robinette Kowal Taiyo Fujii Liz Williams Andrea Hairston William Alexander Eleanor Arnason MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions & Ebooks About the Editor © 2015 Lightspeed Magazine Cover Art by Euclase Ebook Design by John Joseph Adams www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial, July 2015 John Joseph Adams | 550 words Welcome to issue sixty-two of Lightspeed! The Nebulas were presented at the 50th annual Nebula Awards Weekend, held this year in Chicago, Illinois, June 4–7. We’re sorry to say that “We Are the Cloud” by Sam J. Miller (Lightspeed, September 2014) did not win the Nebula Award for best novelette; that honor went to Alaya Dawn Johnson’s excellent story, from The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, “A Guide to the Fruits Of Hawaii.” Congrats to Alaya and to all of the other Nebula nominees, and of course congrats again to Sam for being nominated. Sam’s nomination brings Lightspeed’s lifetime Nebula nomination total to twelve since we launched in June 2010, and we’ve now lost twelve in a row. -

PHOENIX Issue 2, March 2014

PHOENIX Issue 2, March 2014 Bert Schouten wants a revolution “Of course, if the entire English department revolted…” Blurred lines in South Africa Songs for rainy days Albion in London! Content Editorial 2 Tea Time With Bert 3 The Most Boring Course 5 Grasnapolsky Festival 6 Albums Reviews 7 South African English is Lekker 8 Albion Takes Over London 9 Books 11 Editor in Chief: Lars Engels Depury Editor: Marijn Brok Writers: Kiki Drost, Pascal Smit, Arlette Krijgsman, Iris van Nieuwenhuizen, Aisha Mansaray, Erik van Dijk, Margit Wilke Layout: Stanzy Kersten, Marijn Brok 1 Here Comes the Sun A bit of sunshine, a lot of cold wind. The beginning of March has been, as usual, ambivalent in its meteorological decisions. By now, many people are fed up with winter and its lack of warmth. We are eager for afternoons in parks and evenings on balconies but February and March have been largely unaccommodating to our needs so far. A similar sense of frustration and impatience reveals itself in and around class. The third block of the year is hardly one of reflection, as it mostly invites looking forward towards the final block. The first semester is behind us and, like summer, the end of the academic year already beckons. The contents and challenges of these final stages vary enormously for everyone. First- and second-years can look forward to in-depth courses of their own choosing, third-years to internships and BA theses, and many master students like myself try not to shiver in fear from the prospect of having to face the terrifying, gigantic academic beast that is an MA thesis in just a few weeks. -

Making Waves Aug Sept Comp.Pdf

MESSAGE FROM THE Jim Moriarty CEO, Surfrider Foundation http://www.surfrider.org/jims-blog photo: www.jsalasfoto.com It is a match made in heaven: Paul Mc- “Paul asked if I would like to have a lis- Cartney, a legendary artist who has always ten,” said McCoy. “When I heard it, I started had a love for the ocean; and Jack McCoy, dancing around the room because I could the brilliant surf cinematographer who is cap- imagine editing my shots to the song.” turing surfing in The re- a truly unique sult is a video way. that won ‘Best The sto- Music Video’ ryline is just as at the NYC BE perfect: McCoy FILM Short was capturing Festival this footage for his past May, and latest surfing is the Surfrider film, “A Deeper Foundation’s Shade of Blue,” newest PSA. and during the “Blue Sway” is editing process, also featured put one of his sequences to a song off Mc- on the bonus DVD included in the special edi- Cartney’s album “The Fireman.” A mutual tion of McCartney II, in stores now. McCoy’s friend gave McCartney the cut, and Paul im- 25th film, “A Deeper Shade of Blue,” will be in mediately thought McCoy’s images would be theaters late summer, and followed up with a suitable to go with “Blue Sway,” an unreleased DVD/iTunes release. song that was written over 20 years ago. photo: Jack McCoy September 10 Come watch some of the Surfrider Foundation’s celeb- rity supporters (ahem, Jesse Spencer from “House” and Martyn Lenoble) surf First Point in Malibu to raise funds for Here are a few of the the organization at the 6th Annual Celebrity Expression Session. -

Navies and Soft Power

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Newport Papers Special Collections 6-2015 Navies and Soft Power Bruce A. Elleman S.C.M. Paine Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers Recommended Citation Elleman, Bruce A. and Paine, S.C.M., "Navies and Soft Power" (2015). Newport Papers. 42. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-newport-papers/42 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newport Papers by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 42 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 42 Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil-rig fire—fighting the blaze and searching for survivors. U.S. Coast Guard photograph, available at “USGS Multimedia Gallery,” USGS: Science for a Changing World, gallery.usgs.gov/. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its au thenticity. ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4 (e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1) is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superinten- dent of Documents of the U.S.