G7. 7-3.7: a Young Supernova Remnant Probably Associated with the Guest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Which Remained Immutable and Unchanged Thereafter

THE ORIGIN OF THE ELEMENTS BY WILLIAM A. FOWLER CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, PASADENA They [atoms] move in the void and catching each other up jostle together, and some recoil in any direction that may chance, and others become entangled with one another in various degrees according to the symmetry of their shapes and sizes and positions and order, and they remain together and thus the coming into being of composite things is effected. -SIMPLICIUS (6th Century A.D.) It is my privilege to begin our consideration of the history of the universe during this first scientific session of the Academy Centennial with a discussion of the origin of the elements of which the matter of the universe is constituted. The question of the origin of the elements and their numerous isotopes is the modern expression of one of the most ancient problems in science. The early Greeks thought that all matter consisted of the four simple substances-air, earth, fire, and water-and they, too, sought to know the ultimate origin of what for them were the elementary forms of matter. They also speculated that matter consists of very small, indivisible, indestructible, and uncreatable atoms. They were wrong in detail but their concepts of atoms and elements and their quest for origins persist in our science today. When our Academy was founded one century ago, the chemist had shown that the elements were immutable under all chemical and physical transformations known at the time. The alchemist was self-deluded or was an out-and-out charla- tan. Matter was atomic, and absolute immutability characterized each atomic species. -

Neutron Stars: Introduction

Neutron Stars: Introduction Stephen Eikenberry 16 Jan 2018 Original Ideas - I • May 1932: James Chadwick discovers the neutron • People knew that n u clei w ere not protons only (nuclear mass >> mass of protons) • Rutherford coined the name “neutron” to describe them (thought to be p+ e- pairs) • Chadwick identifies discrete particle and shows mass is greater than p+ (by 0.1%) • Heisenberg shows that neutrons are not p+ e- pairs Original Ideas - II • Lev Landau supposedly suggested the existence of neutron stars the night he heard of neutrons • Yakovlev et al (2012) show that he in fact discussed dense stars siiltimilar to a gi ant nucl eus BEFORE neutron discovery; this was immediately adapted to “t“neutron s t”tars” Original Ideas - III • 1934: Walter Baade and Fritz Zwicky suggest that supernova eventtttts may create neutron stars • Why? • Suppg(ernovae have huge (but measured) energies • If NS form from normal stars, then the gravitational binding energy gets released • ESN ~ star … Original Ideas - IV • Late 1930s: Oppenheimer & Volkoff develop first theoretical models and calculations of neutron star structure • WldhWould have con tidbttinued, but WWII intervened (and Oppenheimer was busy with other things ) • And that is how things stood for about 30 years … Little Green Men - I • Cambridge experiment with dipole antennae to map cosmic radio sources • PI: Anthony Hewish; grad students included Jocelyn Bell Little Green Men - II • August 1967: CP 1919 discovered in the radio survey • Nov ember 1967: Bell notices pulsations at P =1.337s -

Beeps, Flashes, Bangs and Bursts

Beeps, Flashes, Big stars work much faster: Bangs and Bursts. 1,000,000 100,000 100,000 100,000 and Chirps. Forever Peter Watson 3 hours! Live fast, Die Young! Peter Watson, Dept. of Physics Change colour, size, brightness •Vast majority of stars are boring: “main- sequence” (aka middle- class) changing very slowly. •Some oscillate: e.g Cepheids •Large bright stars change by factor 3 in brightness Peter Watson Peter Watson If Stars are large.... • we get supernovae • 6 visible in Milky Way over last 1000 years •well understood: work by blocking mechanism • SN 1006: Brightest •very important since period is proportional to Supernova. intrinsic brightness: • Can see remnants of the expanding •i.e. measure the apparent brightness, the period tells shockwave you the actual brightness, so you know how far away Frank Winkler (Middlebury College) et it is al., AURA, NOAO, NSF Peter Watson Peter Watson Remnant of a very Tycho’s old SN Supernova • Part of the veil nebula in X-rays in Cygnus (1572) Sara Wager NASA / CXC / F.J. Lu (Chinese Academy of Sciences) et al. Peter Watson Peter Watson The Crab (M1) •Recorded by Chinese astronomers "I humbly observe that a guest star has appeared; above the star there is a feeble yellow glimmer. If one examines the divination regarding the Emperor, the interpretation [of the presence of this guest star] is the following: The fact that the star has not overrun Bi and that its brightness must represent a person of great value. I demand that the Office of Historiography is informed of this." PW Peter Watson 1054: Crab •Recorded by Chinese astronomers as “guest star” •May have been recorded by Chaco Indians in New • X-rays (in blue) Mexico • + Optical 4 a.m. -

Thursday, September 17, 2009 First Exam, Week from Today Pic of The

Thursday, September 17, 2009 First exam, week from today Astronomy in the news - end of Ramadan with new Moon. Pic of the Day - Andromeda in the Ultraviolet What happens when two white dwarfs spiral together? Larger mass WD has smaller radius Smaller mass, Which WD has the smaller Roche lobe? Larger The smaller mass radius Larger mass, Which fills its Roche Lobe first? Smaller radius Must be the smaller mass As small mass WD loses mass, its radius gets larger, but its Roche Lobe gets smaller! Runaway mass transfer. Small mass WD transfers essentially all its mass to larger mass WD Could end up with one larger mass WD If larger mass hits Mch → could get explosion => Supernova First WD < 1.4 solar masses First WD gets to 1.4 solar masses Classical Nova Recurrent Nova Two WD EXPLOSION! Gravitational Radiation, in-spiral WDs coalesce < 1.4 solar masses > 1.4 solar masses One Big WD EXPLOSION! End of Material for Test 1 Reading for First Exam Chapter 1: 1.2.3, 1.2.4, 1.3.2 Chapter 2: 2.3 Chapter 3: 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.8, 3.9, 3.10 Chapter 4: 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.5 Chapter 5: ALL Sky Watch Extra Credit Due Thursday, in Class Must be typed on regular 8-1/2x11 paper See web site for more details, or ask! See web site for star charts to help guide you where and when to look. Part of the exercise is to learn how to orient yourself and recognize objects and patterns in the sky. -

The Korean 1592--1593 Record of a Guest Star: Animpostor'of The

Journal of the Korean Astronomical Society 49: 00 ∼ 00, 2016 December c 2016. The Korean Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. http://jkas.kas.org THE KOREAN 1592–1593 RECORD OF A GUEST STAR: AN ‘IMPOSTOR’ OF THE CASSIOPEIA ASUPERNOVA? Changbom Park1, Sung-Chul Yoon2, and Bon-Chul Koo2,3 1Korea Institute for Advanced Study, 85 Hoegi-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 02455, Korea; [email protected] 2Department of Physics and Astronomy, Seoul National University, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 08826, Korea [email protected], [email protected] 3Visiting Professor, Korea Institute for Advanced Study, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 02455, Korea Received |; accepted | Abstract: The missing historical record of the Cassiopeia A (Cas A) supernova (SN) event implies a large extinction to the SN, possibly greater than the interstellar extinction to the current SN remnant. Here we investigate the possibility that the guest star that appeared near Cas A in 1592{1593 in Korean history books could have been an `impostor' of the Cas A SN, i.e., a luminous transient that appeared to be a SN but did not destroy the progenitor star, with strong mass loss to have provided extra circumstellar extinction. We first review the Korean records and show that a spatial coincidence between the guest star and Cas A cannot be ruled out, as opposed to previous studies. Based on modern astrophysical findings on core-collapse SN, we argue that Cas A could have had an impostor and derive its anticipated properties. It turned out that the Cas A SN impostor must have been bright (MV = −14:7 ± 2:2 mag) and an amount of dust with visual extinction of ≥ 2:8 ± 2:2 mag should have formed in the ejected envelope and/or in a strong wind afterwards. -

Pulsars and Supernova Remnants

1604–2004: SUPERNOVAE AS COSMOLOGICAL LIGHTHOUSES ASP Conference Series, Vol. 342, 2005 M. Turatto, S. Benetti, L. Zampieri, and W. Shea Pulsars and Supernova Remnants Roger A. Chevalier Dept. of Astronomy, University of Virginia, P.O. Box 3818, Charlottesville, VA 22903, USA Abstract. Massive star supernovae can be divided into four categories de- pending on the amount of mass loss from the progenitor star and the star’s ra- dius. Various aspects of the immediate aftermath of the supernova are expected to develop in different ways depending on the supernova category: mixing in the supernova, fallback on the central compact object, expansion of any pul- sar wind nebula, interaction with circumstellar matter, and photoionization by shock breakout radiation. Models for observed young pulsar wind nebulae ex- panding into supernova ejecta indicate initial pulsar periods of 10 − 100 ms and approximate equipartition between particle and magnetic energies. Considering both pulsar nebulae and circumstellar interaction, the observed properties of young supernova remnants allow many of them to be placed in one of the super- nova categories; the major categories are represented. The pulsar properties do not appear to be related to the supernova category. 1. Introduction The association of SN 1054 with the Crab Nebula and its central pulsar can be understood in the context of the formation of the neutron star in the core collapse and the production of a bubble of relativistic particles and magnetic fields at the center of an expanding supernova. Although the finding of more young pulsars and their wind nebulae initially proceeded slowly, there has recently been a rapid set of discoveries of more such pulsars and nebulae (Camilo 2004). -

Neutron Stars and Their Envelopes A.Y.Potekhin1,2 in Collaboration with G.Chabrier,2 A.D.Kaminker,1 D.G.Yakovlev,1

Dense matter in neutron stars and their envelopes A.Y.Potekhin1,2 in collaboration with G.Chabrier,2 A.D.Kaminker,1 D.G.Yakovlev,1 ... 1Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute, St.Petersburg 2CRAL, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon Introduction: Neutron stars and their importance for fundamental physics Neutron-star envelopes – link between the superdense core and observations Conductivities and thermal structure of neutron star envelopes Atmospheres and thermal radiation spectra of neutron stars with magnetic fields Neutron stars – the densest stars in the Universe Mass and radius: Gravitational energy: average density: Neutron stars on the density – temperature diagram Phase diagram of dense matter. Courtesy of David Blaschke GR effects Gravitational radius Redshift zg: “compactness parameter” u=rg/R ~ 0.3–0.4 “Observed” temperature = Teff /(1+zg) gravity Light rays are bending near the stellar surface, thus allowing one to “look behind the horizon”. “Apparent” radius Neutron stars – the stars with the strongest magnetic field Radio waves P ≈ 1.4 ms – 12 s Ω ≈ 0.5 – 4500 s−1 B In the strong magnetic field of a rapidly rotating neutron star, charged particles are accelerated to relativistic energies, creating coherent radio emission. Therefore many neutron stars are observed as pulsars. Ω2 B2 Ω1 ω B1 Gravitational waves Radio waves Binary neutron stars emit gravitational waves (losing the angular momentum) and undergo relativistic precession. Prediction L.D.Landau (1931) – anticipation [L.D.Landau, “On the theory of stars,” Physikalische Zs. Sowjetunion 1 (1932) 285]: for stars with M>1.5M☼ “density of matter becomes so great that atomic nuclei come in close contact, foming one gigantic nucleus’’. -

Cosmic Catastrophes Wheeler 309N Spring 2008 February 25, 2008 (49490) Review for Test #2 SUPERNOVAE

Cosmic Catastrophes Wheeler 309N Spring 2008 February 25, 2008 (49490) Review for Test #2 SUPERNOVAE Historical Supernovae in the Milky Way - several seen and recorded with naked eye in last 2000 years. SN 386 earliest on record, SN 1006 brightest, SN 1054, now the Crab Nebula, contains a rapidly rotating pulsar and suggestions of a jet. Tycho 1572, Kepler 1604. Cas A, not clearly seen about 1680, shows evidence for jets, and a dim compact object in the center. The events that show compact objects also seem to show evidence of “elongated” explosions or “jets.” SN1006, SN 1572 and SN 1604 were probably Type 1a. SN 1987A in a very nearby galaxy shows elongated ejecta, produced neutrinos so we know it was powered by core collapse. Extragalactic Supernovae - many, but dimmer, more difficult to study. Common elements produced in supernovae - carbon, oxygen, magnesium, silicon, sulfur, calcium - are built up by adding “building blocks” of helium nuclei consisting of four particles, 2 protons and 2 neutrons. Type I supernovae - no evidence for hydrogen in spectrum. Type II supernovae - definite evidence for hydrogen in spectrum. Type Ia supernovae - brightest, no hydrogen or helium, avoid spiral arms, occur in elliptical galaxies, origin in lower mass stars. Observe silicon early on, iron later. Unregulated burning, explosion in quantum pressure supported carbon/oxygen white dwarf of Chandrasekhar mass. Expected to occur in a binary system so white dwarf can grow. Star is completely disrupted, no neutron star or black hole. Light curve shows peak lasting about a week. Type II Supernovae - explode in spiral arms, never occur in elliptical galaxies, normal hydrogen, massive stars, recently born, short lived. -

Variable Star

Variable star A variable star is a star whose brightness as seen from Earth (its apparent magnitude) fluctuates. This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are classified as either: Intrinsic variables, whose luminosity actually changes; for example, because the star periodically swells and shrinks. Extrinsic variables, whose apparent changes in brightness are due to changes in the amount of their light that can reach Earth; for example, because the star has an orbiting companion that sometimes Trifid Nebula contains Cepheid variable stars eclipses it. Many, possibly most, stars have at least some variation in luminosity: the energy output of our Sun, for example, varies by about 0.1% over an 11-year solar cycle.[1] Contents Discovery Detecting variability Variable star observations Interpretation of observations Nomenclature Classification Intrinsic variable stars Pulsating variable stars Eruptive variable stars Cataclysmic or explosive variable stars Extrinsic variable stars Rotating variable stars Eclipsing binaries Planetary transits See also References External links Discovery An ancient Egyptian calendar of lucky and unlucky days composed some 3,200 years ago may be the oldest preserved historical document of the discovery of a variable star, the eclipsing binary Algol.[2][3][4] Of the modern astronomers, the first variable star was identified in 1638 when Johannes Holwarda noticed that Omicron Ceti (later named Mira) pulsated in a cycle taking 11 months; the star had previously been described as a nova by David Fabricius in 1596. This discovery, combined with supernovae observed in 1572 and 1604, proved that the starry sky was not eternally invariable as Aristotle and other ancient philosophers had taught. -

Chapter 13 – the Deaths of Stars

Chapter 13 – The Deaths of Stars On July 4, 1054, Chinese astronomers noted a new bright star in the constellation of Taurus. The “guest star” was so bright it could be seen in daylight for almost a month! This event was recorded by several independent chinese astronomers and could be observed for almost 2 years. This dramatic event heralded the death throes of a massive star only 6500 light years away. When we turn modern day telescopes towards Taurus we observe the fallout from this immense explosion. This region is known as the Crab Nebula (M1). Located inside the nebula is a pulsar – a fast rotating neutron star, the final dense remains of the star that went supernova only a millenium ago... As with many properties of stars that we have seen, how a star ends its life depends on its mass. The common feature across the mass range is that stars “die” when they run out of fuel, because now there is no way to resist the compression force of gravity. The Death of Low Mass Stars The core of a star heats up in response to gravitational contraction. Therefore, low mass stars never get very hot. In fact, stars below 0.4 solar masses only get hot enough to fuse hydrogen (and only in p-p chain reactions). This low temperature means that the hydrogen fuel is consumed relatively slowly. In addition, as we saw in a previous lecture, very low mass stars are completely convective. The large scale convection continually brings fresh hydrogen fuel to the centre of the star. -

Neutron Star

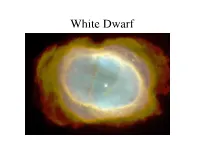

Phys 321: Lecture 8 Stellar Remnants Prof. Bin Chen, Tiernan Hall 101, [email protected] Evolution of a low-mass star Planetary Nebula Main SequenceEvolution and Post-Main-Sequence track of an 1 Stellar solar Evolution-mass star Post-AGB PN formation Superwind First He shell flash White dwarf TP-AGB Second dredge-up He core flash ) Pre-white dwarf L / L E-AGB ( 10 He core exhausted Log RGB Ring Nebula (M57) He core burning First Red: Nitrogen, Green: Oxygen, Blue: Helium dredge-up H shell burning SGB Core contraction H core exhausted ZAMS To white dwarf phase 1 M Log (T ) 10 e Sirius B FIGURE 4 A schematic diagram of the evolution of a low-mass star of 1 M from the zero-age main sequence to the formation of a white dwarf star. The dotted ph⊙ase of evolution represents rapid evolution following the helium core flash. The various phases of evolution are labeled as follows: Zero-Age-Main-Sequence (ZAMS), Sub-Giant Branch (SGB), Red Giant Branch (RGB), Early Asymptotic Giant Branch (E-AGB), Thermal Pulse Asymptotic Giant Branch (TP-AGB), Post- Asymptotic Giant Branch (Post-AGB), Planetary Nebula formation (PN formation), and Pre-white dwarf phase leading to white dwarf phase. and becomes nearly isothermal. At points 4 in Fig. 1, the Schönberg–Chandrasekhar limit is reached and the core begins to contract rapidly, causing the evolution to proceed on the much faster Kelvin–Helmholtz timescale. The gravitational energy released by the rapidly contracting core again causes the envelope of the star to expand and the effec- tive temperature cools, resulting in redward evolution on the H–R diagram. -

White Dwarf Properties of a White Dwarf

White Dwarf Properties of a White Dwarf • Contains most of star’s original mass • Yet diameter is roughly Earth’s diameter • Density about 3x109 kg/m3 One teaspoon would weigh 15 tons Surface gravity = 1.3 x 105 g vesc = 0.02 x speed of light • Teff = 10,000 K, MV = +11 (Sun is +4.8) White Dwarf • After planetary nebula dissipates, all that’s left is the hot degenerate core • Remnant core of M<8 Msun star • M<4Msun: C-O white dwarf (never ignited C) • M=4-8Msun: O-Ne-Mg white dwarf • Supported by electron degeneracy pressure • No fusion, no contraction, just cooling. For eternity. Properties of a White Dwarf Structure of isolated WD Degenerate CO core (5000 km) Thin (100m) atmosphere Structure of isolated WD •At these densities, WD is supported by electron degeneracy pressure. • This has a profound impact on its structure (M vs. R) Structure of isolated WD • WD consists of gas of ionized C+O nuclei and electrons (overall neutral) • Electrons are fermions, i.e. spin±1/2 particles (protons & neutrons as well) • 2 important quantum-mechanical things: Pauli exclusion principle; Heisenberg uncertainty principle Structure of isolated WD • Pauli exclusion principle: no 2 identical fermions can occuply exact same quantum mechanical state (e.g., energy, angular momentum, spin) • Heisenberg uncertainty principle: it is impossible to define position and momentum simultaneously to accuracy better than ~Planck’s constant for the product of the uncertainties: px is x-component (Δx)(Δpx) ≥ ћ/2 of momentum Structure of isolated WD Chandrasekhar mass limit There is an upper limit to the mass of a WD of 1.4 solar masses, set by electron degeneracy pressure… Above this limit, WD is unstable Upper limit on mass of white dwarfs Electron degeneracy can’t support more than 1.4 Msun Mass transfer in binary systems • Isolated white dwarf boring, simply cools forever (makes them good “clocks”) • White dwarfs in binary systems are more interesting • If binary stars are close enough (<1 AU), mass transfer can occur… Stars in a binary system may have more complex evolution….