An Aboriginal Australian Record of the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Eva Bischoff Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth- Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Department of International History Trier University Trier, Germany Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-030-32666-1 ISBN 978-3-030-32667-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32667-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

Summer Constellations

Night Sky 101: Summer Constellations The Summer Triangle Photo Credit: Smoky Mountain Astronomical Society The Summer Triangle is made up of three bright stars—Altair, in the constellation Aquila (the eagle), Deneb in Cygnus (the swan), and Vega Lyra (the lyre, or harp). Also called “The Northern Cross” or “The Backbone of the Milky Way,” Cygnus is a horizontal cross of five bright stars. In very dark skies, Cygnus helps viewers find the Milky Way. Albireo, the last star in Cygnus’s tail, is actually made up of two stars (a binary star). The separate stars can be seen with a 30 power telescope. The Ring Nebula, part of the constellation Lyra, can also be seen with this magnification. In Japanese mythology, Vega, the celestial princess and goddess, fell in love Altair. Her father did not approve of Altair, since he was a mortal. They were forbidden from seeing each other. The two lovers were placed in the sky, where they were separated by the Celestial River, repre- sented by the Milky Way. According to the legend, once a year, a bridge of magpies form, rep- resented by Cygnus, to reunite the lovers. Photo credit: Unknown Scorpius Also called Scorpio, Scorpius is one of the 12 Zodiac constellations, which are used in reading horoscopes. Scorpius represents those born during October 23 to November 21. Scorpio is easy to spot in the summer sky. It is made up of a long string bright stars, which are visible in most lights, especially Antares, because of its distinctly red color. Antares is about 850 times bigger than our sun and is a red giant. -

Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP

SIERRA COLLEGE OBSERVATIONAL ASTRONOMY LABORATORY EXERCISE Lab N03: Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP OBJECTIVE: Learn about the Celestial Coordinate System. Learn about stellar designations. Learn about deep sky object designations. INTRODUCTION: The Horizon Coordinate System is simple, but flawed, because the altitude and azimuth measures of stars change as the sky rotates. Astronomers have developed an improved scheme called the Celestial Coordinate System, which is fixed with the stars. The two coordinates are Right Ascension and Declination. Declination ranges from the North Celestial Pole to the South Celestial Pole, with the Celestial Equator being a line around the sky at the midline of those two extremes. We will use these coordinates when navigating using the SC001 and SC002 charts. There are many ways to designate stars. The most common is called the Bayer designations. The Bayer designation of a star starts with a Greek letter. The brightest star in the constellation gets “alpha” (the first letter in the Greek alphabet), the second brightest star gets “beta,” and so on. (The Greek alphabet is shown below.) The Bayer designation must also include the constellation name. There are only 24 letters in the Greek alphabet, so this system is obviously very limited. The Greek alphabet 1) Alpha 7) Eta 13) Nu 19) Tau 2) Beta 8) Theta 14) Xi 20) Upsilon 3) Gamma 9) Iota 15) Omicron 21) Phi 4) Delta 10) Kappa 16) Pi 22) Chi 5) Epsilon 11) Lambda 17) Rho 23) Psi 6) Zeta 12) Mu 18) Sigma 24) Omega A more extensive naming system is called the Flamsteed designation. -

And Space-Based Photometry

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–17 (2002) Printed 5 December 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Transit analysis of the CoRoT-5, CoRoT-8, CoRoT-12, CoRoT-18, CoRoT-20, and CoRoT-27 systems with combined ground- and space-based photometry St. Raetz1,2,3⋆, A. M. Heras3, M. Fern´andez4, V. Casanova4, C. Marka5 1Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics T¨ubingen (IAAT), University of T¨ubingen, Sand 1, D-72076 T¨ubingen, Germany 2Freiburg Institute of Advanced Studies (FRIAS), University of Freiburg, Albertstraße 19, D-79104 Freiburg, Germany 3Science Support Office, Directorate of Science, European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESA/ESTEC), Keplerlaan 1, 2201 AZ Noordwijk, The Netherlands 4Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, CSIC, Apdo. 3004, 18080 Granada, Spain 5Instituto Radioastronom´ıa Milim´etrica (IRAM), Avenida Divina Pastora 7, E-18012 Granada, Spain Accepted 2018 November 8. Received: 2018 November 7; in original from 2018 April 6 ABSTRACT We have initiated a dedicated project to follow-up with ground-based photometry the transiting planets discovered by CoRoT in order to refine the orbital elements, constrain their physical parameters and search for additional bodies in the system. From 2012 September to 2016 December we carried out 16 transit observations of six CoRoT planets (CoRoT-5b, CoRoT-8b, CoRoT-12b, CoRoT-18b, CoRoT-20 b, and CoRoT-27b) at three observatories located in Germany and Spain. These observations took place between 5 and 9 yr after the planet’s discovery, which has allowed us to place stringent constraints on the planetary ephemeris. In five cases we obtained light curves with a deviation of the mid-transit time of up to ∼115 min from the predictions. -

The Denver Observer June 2016

The Denver JUNE 2016 OBSERVER Mercury transits the Sun on May 9, 2016. The planet, seen at the lower left of the Sun's face, has a diameter of about 3,000 miles, but the Sun's 870,000 mile cross-section dwarfs the planet—even though the Sun is seen here at twice Mercury's distance from us. (Note the planet-sized sunspots above-left of solar center.) Image © Ron Pearson. JUNE SKIES by Zachary Singer The Solar System the Martian surface reveals itself. On observing runs over the last few If you haven’t been observing Mars, the “unusually bright orange weeks, with good seeing, early views did indeed yield so-so results, but object in Libra,” now is a really good time: As June begins, the plan- improved noticeably as the planet neared its highest point in the south. et is just past opposition, and even more recently past its closest ap- I was able to make out the Syrtis Major region easily, even though proach to Earth, when the planet’s disk spanned a full 18.6 arcseconds. moonlight was a factor in the initial sessions. It looms large in a telescope now, and even instruments of moderate One great tool for power bring satisfying images at 100 or 150X. By midmonth, Mars improving your view Sky Calendar will be highest around 11 PM, with the disk slightly smaller, at 17.9”; is a “Moon filter.” 4 New Moon by June 30th, though, the planet will have already crossed the Meridian By bringing the sheer 12 First-Quarter Moon at 10 PM, before the sky brightness of Mars’ mag- 20 Full Moon In the Observer is fully dark, and the disk nitude -2 disk down a 27 Last-Quarter Moon will have shrunk some- notch, the moon filter President’s Message . -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

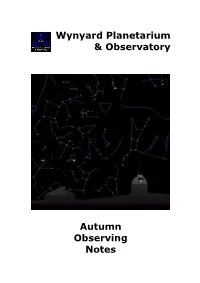

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

The Midnight Sky: Familiar Notes on the Stars and Planets, Edward Durkin, July 15, 1869 a Good Way to Start – Find North

The expression "dog days" refers to the period from July 3 through Aug. 11 when our brightest night star, SIRIUS (aka the dog star), rises in conjunction* with the sun. Conjunction, in astronomy, is defined as the apparent meeting or passing of two celestial bodies. TAAS Fabulous Fifty A program for those new to astronomy Friday Evening, July 20, 2018, 8:00 pm All TAAS and other new and not so new astronomers are welcome. What is the TAAS Fabulous 50 Program? It is a set of 4 meetings spread across a calendar year in which a beginner to astronomy learns to locate 50 of the most prominent night sky objects visible to the naked eye. These include stars, constellations, asterisms, and Messier objects. Methodology 1. Meeting dates for each season in year 2018 Winter Jan 19 Spring Apr 20 Summer Jul 20 Fall Oct 19 2. Locate the brightest and easiest to observe stars and associated constellations 3. Add new prominent constellations for each season Tonight’s Schedule 8:00 pm – We meet inside for a slide presentation overview of the Summer sky. 8:40 pm – View night sky outside The Midnight Sky: Familiar Notes on the Stars and Planets, Edward Durkin, July 15, 1869 A Good Way to Start – Find North Polaris North Star Polaris is about the 50th brightest star. It appears isolated making it easy to identify. Circumpolar Stars Polaris Horizon Line Albuquerque -- 35° N Circumpolar Stars Capella the Goat Star AS THE WORLD TURNS The Circle of Perpetual Apparition for Albuquerque Deneb 1 URSA MINOR 2 3 2 URSA MAJOR & Vega BIG DIPPER 1 3 Draco 4 Camelopardalis 6 4 Deneb 5 CASSIOPEIA 5 6 Cepheus Capella the Goat Star 2 3 1 Draco Ursa Minor Ursa Major 6 Camelopardalis 4 Cassiopeia 5 Cepheus Clock and Calendar A single map of the stars can show the places of the stars at different hours and months of the year in consequence of the earth’s two primary movements: Daily Clock The rotation of the earth on it's own axis amounts to 360 degrees in 24 hours, or 15 degrees per hour (360/24). -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

2014-08 AUG.Pdf

August First Light Newsletter 1 message August, 2014 Issue 122 AlachuaAstronomyClub.org North Central Florida's Amateur Astronomy Club Serving Alachua County since 1987 BREAKING NEWS -- ROSETTA HAS JUST ARRIVED AT COMET 67/P Member Member Astronomical League Initiated in late 1993 by Europe and the USA, and launched in 2004, the International Rosetta Mission is an historic first: Send a spacecraft to chase and orbit a comet, ride along as the comet plunges sun ward to learn how a frozen comet transforms by the Sun's warmth, and dispatch a controlled lander to make in situ measurements and make first images Member from a comet's surface. NASA Night Sky Network Ten years later Rosetta has now arrived at Comet 67P/Churyumov- Gerasimenko and just successfully made orbit today, 2014 August 6! Unfortunately, global events have foreshadowed this memorable event and news media have largely ignored this impressive space mission. AAC Member photo: The Rosetta comet mission may be the beginning of a story that will tell more about us -- both about our origins and evolution. (Hence, its name "rosetta" for the black basalt stone with inscriptions giving the first clues to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics.) Pictures received over past weeks are remarkable with the latest in the past 24 hours showing awesome and incredible detail including views that show the comet is a connected binary object rotating as a unit in 12 hours. Anyone see the glorious pairing of Venus and Jupiter this morning (2016 Aug. 18)? For images see http://www.esa.int/ spaceinimages/Missions/ Except when Mars is occasionally brighter Rosetta than Jupiter, these two planets are the brightest nighttime sky objects (discounting Example Image (Aug.