Entertainment-Education Behind the Scenes: Case Studies for Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissertation Formatted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Beyond Transition: Life Course Challenges of Trans* People A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Andrew Rene Seeber Committee in charge: Professor Verta Taylor, Committee Co-Chair Professor France Winddance Twine, Committee Co-Chair Professor Alicia Cast Professor Leila Rupp December 2015 The dissertation of Andrew Rene Seeber is approved. ____________________________________________ Alicia Cast ____________________________________________ Leila Rupp ____________________________________________ Verta Taylor, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ France Winddance Twine, Committee Co-Chair December 2015 Beyond Transition: Life Course Challenges of Trans* People Copyright © 2015 by Andrew Rene Seeber iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the many people who opened their homes and life stories to me, making this project possible. Your time, good humor, and generosity are much appreciated. I would also like to thank my co-chairs, Verta Taylor and France Winddance Twine, for their hours of work, attention, and support in guiding me through the research and writing process. Thank you to my committee members, Alicia Cast and Leila Rupp, for their theoretical and editorial insights. Thank you to many colleagues and friends, especially Noa Klein and Elizabeth Rahilly, for places to sleep, challenging conversations, and continuous cheerleading. I would like to thank my family for always being there and supporting me from afar, even when I confused them with pronouns, needed a place to visit for a break, or asked them to travel completely across the country for my wedding. Finally, I would like to thank my wonderful wife, Haley Cutler, for her inspiration, support, patience for graduate student life, and most importantly, her love. -

“My Voice Speaks for Itself”: the Experiences of Three Transgender Students in Secondary School Choral Programs

“MY VOICE SPEAKS FOR ITSELF”: THE EXPERIENCES OF THREE TRANSGENDER STUDENTS IN SECONDARY SCHOOL CHORAL PROGRAMS By Joshua Palkki A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Music Education—Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT “MY VOICE SPEAKS FOR ITSELF”: THE EXPERIENCES OF THREE TRANSGENDER STUDENTS IN SECONDARY SCHOOL CHORAL PROGRAMS By Joshua Palkki Is choral music education in America at a “trans(gender) tipping point”? With the purpose of furthering and enhancing the sociocultural dialogue surrounding LGBTQA issues in music education and to improve vocal/choral instruction for trans students, this multiple narrative case study explored the musical lives and lived experiences of trans students in high school choral music programs. The two grand tour problems of this study were: • To describe how transgender students enrolled in secondary school choral music programs navigate their gender identity in the choral context. • To describe if/how transgender students in secondary school choral programs were supported by groups including their choral teachers, choral peers, and school administrators. The emergent research design employed narrative inquiry and ethnographic techniques in order to honor and highlight voices of the three participants: Sara, Jon, and Skyler (pseudonyms). The stories of these three students revealed the importance of context and geography in shaping the experiences of trans youth at school. Additionally, the connection or lack thereof between voice and gender identity was different for each of the participants. The policies of the students’ school districts, high schools (administrators), choral programs, and outside music organizations (e.g., state music education organizations) shaped and influenced how Sara, Jon, and Skyler navigated their trans identity within the high school choral context. -

4099.46 $3951.81 $2422.68 $398.76

CITY OF BOZEMAN EXPENDITURE APPROVAL LIST CHECK DATE 10/2-10/8/19 Vendor Name Budget Account Description 1 Description 2 Transaction Amount 360 OFFICE SOLUTIONS 010-3010-421.20-10 (2) 8GB FLASH DRIVE (4 CT) COPY PAPER $42.82 010-3010-421.20-10 (2) 8 GB FLASH PK OF 3 (5) 4 GB FLASH $88.07 010-3010-421.20-10 (4 CT) COPY PAPER $177.88 010-3010-421.20-10 PENS, PPRCLIPS, LEGAL PD CLIPBOARD - PATROL $89.99 $398.76 ACHIEVE MONTANA 010-0000-204.32-43 PAYROLL SUMMARY $2,422.68 $2,422.68 AE2S, INC 600-4610-441.50-50 SOURDOUGH WTP LEAK STUDY PROF SRVCS THRU 8/30/19 $327.50 600-4610-441.50-50 PEAR STREET BOOSTER REHAB PROF SRVCS THRU 8/30/19 $3,624.31 $3,951.81 AFLAC 010-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $2,180.28 010-0000-204.30-04 PAYROLL SUMMARY $93.40 010-0000-204.32-01 PAYROLL SUMMARY $578.00 100-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $101.66 100-0000-204.32-01 PAYROLL SUMMARY $124.93 111-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $158.21 111-0000-204.32-01 PAYROLL SUMMARY $88.24 112-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $41.08 112-0000-204.32-01 PAYROLL SUMMARY $76.83 115-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $82.10 115-0000-204.32-01 PAYROLL SUMMARY $42.90 600-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $15.60 600-0000-204.30-04 PAYROLL SUMMARY $26.85 620-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $15.60 620-0000-204.30-04 PAYROLL SUMMARY $26.85 640-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $70.58 650-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $41.08 710-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $72.15 010-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $192.86 111-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $16.20 112-0000-204.30-03 PAYROLL SUMMARY $16.20 640-0000-204.30-03 -

Nysba Spring 2020 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2020 | VOL. 31 | NO. 2 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association In This Issue n A Case of “Creative Destruction”: Takeaways from the 5Pointz Graffiti Dispute n The American Actress, the English Duchess, and the Privacy Litigation n The Battle Against the Bots: The Legislative Fight Against Ticket Bots ....and more www.nysba.org/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION In The Arena: A Sports Law Handbook Co-sponsored by the New York State Bar Association and the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section As the world of professional athletics has become more competitive and the issues more complex, so has the need for more reliable representation in the field of sports law. Written by dozens of sports law attorneys and medical professionals, In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook is a reflection of the multiple issues that face athletes and the attorneys who represent them. Included in this book are chapters on representing professional athletes, NCAA enforcement, advertising, sponsorship, intellectual property rights, doping, concussion-related issues, Title IX and dozens of useful appendices. Table of Contents Intellectual Property Rights and Endorsement Agreements How Trademark Protection Intersects with the Athlete’s EDITORS Right of Publicity Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. Collective Bargaining in the Big Three David Krell, Esq. Agency Law Sports, Torts and Criminal Law PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES 2013 | 539 pages Role of Advertising and Sponsorship in the Business of Sports PN: 4002 (Print) Doping in Sport: A Historical and Current Perspective PN: 4002E (E-Book) Athlete Concussion-Related Issues Non-Members $80 Concussions—From a Neuropsychological and Medical Perspective NYSBA Members $65 In-Arena Giveaways: Sweepstakes Law Basics and Compliance Issues Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low flat Navigating the NCAA Enforcement Process rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regardless of the number of items shipped. -

Distrito Centroamérica-Panamá Año 2020

Distrito Centroamérica-Panamá Año 2020 CAN CIO NERO Lasallista Cancionero Lasallista Presentación El Cancionero Lasallista pretende ser un apoyo para la evangelización de niños y jóvenes que participan en el Movimiento Misionero Lasallista. En esta primera versión se presentan canciones de uso litúrgico y popular común en nuestros cinco países y, a la vez, canciones lasallistas. En la segunda versión, se pretende que este cancionero cuente con los acordes musicales para ejecutar en guitarra y la actualización de las canciones que se utilizan en cada sector de nuestro Distrito. En un adenda posterior, se contará con las canciones para su reproducción digital. El uso del cancionero lasallista contribuirá a la identidad colectiva, a la animación de las reuniones; sobre todo a reconocer, vivir y celebrar la presencia de Dios en medio de nosotros. El uso del cancionero puede extenderse a toda la comunidad educativa (en reuniones de los docentes, eucaristías, escuela de padres, entre otras). Es aporte del Movimiento Misionero para toda la comunidad lasallista. Sin embargo, es valioso que los niños y jóvenes miembros; por lo que se sugiere tener una versión impresa de este cancionero. Les motivamos a colaborar en la elaboración de recursos para nuestros grupos intencionales, a enviar propuestas y sugerencias para el trabajo en Red de todos los responsables de los grupos infantiles y juveniles. Agradecemos a la Oficina Distrital de Comunicaciones, Redes y Tecnología por el trabajo realizado. ¡Viva Jesús en nuestros corazones! Red del Movimiento Misionero ÍNDICE CANTOS DE ANIMACIÓN CANTOS PENITENCIALES 1. Mira lo que hizo en mí Jesús 13 31. Señor ten piedad (1) 29 2. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

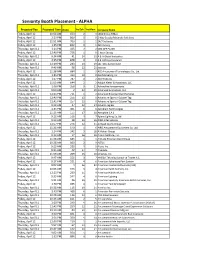

Seniority Rank with Extimated Times.Xlsx

Seniority Booth Placement ‐ ALPHA Projected Day Projected Time Order Yrs Exh Yrs Mem Company Name Friday, April 12 10:54 AM 633 2 3 1602 Group TiMax Friday, April 12 2:10 PM 860 002 Way Supply/Motorola Solutions Friday, April 12 11:51 AM 700 1 2 24/7 Software Friday, April 12 1:45 PM 832 0 1 360 Karting Thursday, April 11 3:14 PM 435 7 2 50% OFF PLUSH Friday, April 12 12:40 PM 756 105‐hour Energy Thursday, April 11 9:34 AM 41 24 10 A & A Global Industries Friday, April 12 2:25 PM 878 0 0 A.E. Jeffreys Insurance Thursday, April 11 12:29 PM 243 13 19 abc rides Switzerland Thursday, April 11 9:49 AM 58 22 25 accesso Friday, April 12 11:38 AM 684 1 3 ACE Amusement Technologies Co., Ltd. Thursday, April 11 1:46 PM 333 10 8 Ace Marketing Inc. Friday, April 12 1:07 PM 787 0 2 ADJ Products Friday, April 12 11:03 AM 644 2 2 Adolph Kiefer & Associates, LLC Thursday, April 11 2:08 PM 358 9 11 Adrenaline Amusements Thursday, April 11 9:00 AM 2 33 29 Advanced Animations, LLC Friday, April 12 12:01 PM 711 1 2 Advanced Entertainment Services Thursday, April 11 12:40 PM 256 13 0 Adventure Sports HQ Laser Tag Thursday, April 11 12:41 PM 257 13 0 Adventure Sports HQ Laser Tag Thursday, April 11 9:39 AM 47 23 24 Adventureglass Thursday, April 11 2:45 PM 401 8 8 Aerodium Technologies Thursday, April 11 11:13 AM 155 17 18 Aerophile S.A.S Friday, April 12 9:12 AM 516 4 7 Aglare Lighting Co.,ltd Thursday, April 11 9:23 AM 28 25 26 AIMS International Thursday, April 11 12:57 PM 276 12 11 Airhead Sports Group Friday, April 12 11:26 AM 670 1 6 AIRO Amusement Equipment Co. -

Redalyc.La Telenovela En Mexico

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Sistema de Información Científica Guillermo Orozco Gómez La telenovela en mexico: ¿de una expresión cultural a un simple producto para la mercadotecnia? Comunicación y Sociedad, núm. 6, julio-diciembre, 2006, pp. 11-35, Universidad de Guadalajara México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=34600602 Comunicación y Sociedad, ISSN (Versión impresa): 0188-252X [email protected] Universidad de Guadalajara México ¿Cómo citar? Fascículo completo Más información del artículo Página de la revista www.redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto La telenovela en mexico: ¿de una expresión cultural a un simple producto para la mercadotecnia?* GUILLERMO OROZCO GÓMEZ** Se enfatizan en este ensayo algunos It is argued in this essay that fictional de los principales cambios que el for- drama in the Tv screen is becoming mato de la ficción televisiva ha ido more and more a simple commodity. sufriendo desde sus orígenes, como If five decades ago, one of the key relato marcado fuertemente por la marks of Mexican Tv drama was its cultura y los modelos de comporta- strong cultural identity, and in fact miento característicos de su lugar y the audience’s self recognition in their su época. En este recorrido se hace plots made them so attractive and referencia a la telenovela “Rebelde” unique as media products, today tele- producida y transmitida por Televisa novelas are central part of mayor mer- en México a partir de 2005. -

Comunicar Derechos En El Posconflicto. Caja De Herramientas Y Estrategias

PAZ, JUSTICIA E INSTITUCIONES 16 SÓLIDAS Organización Objetivos de de las Naciones Unidas Desarrollo para la Educación, Sostenible la Ciencia y la Cultura COMUNICAR DERECHOS EN EL POSCONFLICTO CAJA DE HERRAMIENTAS Y ESTRATEGIAS 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Comunicar derechos en el posconflicto. Caja de herramientas y estrategias es el resultado de un esfuerzo conjunto entre el Banco Mundial y la UNESCO, con el financiamiento del Nordic Trust Fund del Banco Mundial. Queremos agradecer a las entidades gubernamentales y estatales de Colombia y a las organi- zaciones de la sociedad civil cuya participación en las discusiones sobre esta caja de herramien- tas y estrategias ha proporcionado insumos valiosos: el Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho; la Defensoría del Pueblo; la Unidad para la Atención y Reparación Integral a las Víctimas; la Consejería Presidencial para los Derechos Humanos; el Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores; la Policía Nacional; la Procuraduría General de la Nación; la Secretaría de Transparencia; la Vice- presidencia de la República; la Asociación Nacional de Afrocolombianos Desplazados (AFRO- DES); la Asociación Nacional de Usuarios Campesinos (ANUC); Dejusticia; el Instituto Popular de Capacitación; Meta con Mirada de Mujer; Narrar para Vivir; el Proceso de Comunidades Ne- gras (PCN); y SISMA Mujer. En particular, agradecemos a los participantes y co-organizadores de los talleres llevados a cabo en noviembre de 2018 en Bogotá, Colombia, y de los eventos realizados en el marco de la celebración del Día Internacional del Derecho de Acceso Universal a la Información y la Conferencia Latinoamericana de Periodismo de Investigación (COLPIN). El apoyo de la Universidad de los Andes y de la Universidad del Rosario en distintos momentos, también fue especialmente importante. -

Attractions Management News 7Th August 2019 Issue

Find great staff™ Jobs start on page 27 MANAGEMENT NEWS 7 AUGUST 2019 ISSUE 136 www.attractionsmanagement.com Universal unveils Epic Universe plans Universal has finally confirmed plans for its fourth gate in Orlando, officially announcing its Epic Universe theme park. Announced at an event held at the Orange County Convention Center in Orlando, Epic Universe will be the latest addition to Florida's lucrative theme park sector and has been touted as "an entirely new level of experience that forever changes theme park entertainment". "Our new park represents the single- largest investment Comcast has made ■■The development almost doubles in its theme park business and in Florida Universal's theme park presence in Orlando overall,” said Brian Roberts, Comcast chair and CEO. "It reflects the tremendous restaurants and more. The development excitement we have for the future of will nearly double Universal’s total our theme park business and for our available space in central Florida. entire company’s future in Florida." "Our vision for Epic Universe is While no specific details have been historic," said Tom Williams, chair and revealed about what IPs will feature in CEO for Universal Parks and Resorts. This is the single largest the park, Universal did confirm that the "It will become the most immersive and investment Comcast has made 3sq km (1.2sq m) site would feature innovative theme park we've ever created." in its theme park business an entertainment centre, hotels, shops, MORE: http://lei.sr/J5J7j_T Brian Roberts FINANCIALS NEW AUDIENCES -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

Karaoke Track List

Track Artist & Title Track Number 2 Unlimited - No Limits 1 2Pac - Changes 2 50 Cent - In da club 3 A Ha - Take On Me 4 ABBA - Dancing Queen 5 ABBA - Does Your Mother Know 6 ABBA - Fernando 7 ABBA - Gimme Gimme Gimme A Man After Midnight 8 ABBA - Knowing Me Knowing You 9 ABBA - Mama Mia 10 ABBA - Money Money Money 11 ABBA - SOS 12 ABBA - Super Trouper 13 ABBA - Take A Chance On Me 14 ABBA - Thank You For The Music 15 ABBA - Voulez-vous 16 ABBA - Waterloo 17 ACDC - Back In Black 18 Ace Of Base - All That She Wants 19 Ace Of Base - The Sign 20 Adele - Cold Shoulder 21 Adele - Hometown Glory 22 Adele - Make you feel my love 23 Adele - Rolling In The Deep 24 Aerosmith - Dude (Looks Like A Lady) 25 Afroman - Because I Got High 26 Alanah Miles - Black Velvet 27 Alanis Morrisette - Ironic 28 Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah 29 Alexis Jordan - Happiness 30 Alice Cooper - Poison 31 Alice Deejay - Better Off Alone 32 All Saints - Black Coffee 33 All Saints - Never Ever 34 All Saints - Pure Shores 35 All Saints - Under The Bridge 36 Alphaville - Big In Japan 37 Amy Macdonald - This Is The Life 38 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black 39 Amy Winehouse - Love is a losing game 40 Amy Winehouse - Rehab 41 Amy Winehouse - Valerie (Mark Ronson Version) 42 Anastacia - Left Outside Alone 43 Andy Grammer - Honey, I'm Good 44 Anne-Marie - 2002 45 Anne-Marie - Ciao Adios 46 Annie Lennox - Little Bird 47 Annie Lennox - Walking On Broken Glass 48 Aqua - Barbiegirl 49 Aqua - Doctor Jones 50 Arctic Monkeys - I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor 51 Aretha Franklin - Respect