Maritime Security: Strengthening International and Interagency Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maritime Terrorism

1 Maritime terrorism naval bases, offshore oil and gas facilities, other By Emilio Bonagiunta, Maritime Security Consultant critical infrastructure, or the maritime trade itself.ii Operations of this kind are reportedly part of Al-Qaeda's maritime strategy.iii Past here are two main forms in which attacks against oil facilities and tankers in Saudi terrorist groups benefit from the Arabia and Yemen demonstrate that terrorist T vastness and lawlessness of the sea: by networks in the region have ambitions to conducting attacks against sea-based targets and severely disrupt energy supplies from the by using the sea to transport weapons, militants Arabian Peninsula. A successful series of large- and other support means from one place to the scale attacks against the oil industry would have i other. In both cases, the low level of control and tremendous impacts on international energy law enforcement provides a beneficial markets and the global economy. It is from this environment for preparation and conduction perspective that Al-Qaeda poses a serious threat terrorist operations in the maritime domain, against maritime trade.iv unthinkable of on the ground. Yet, the fact that these fears have not Along with this, offshore assets and critical materialized can be attributed to a variety of infrastructure on the coast are seen as high-value factors: greater vigilance and measures adopted targets for terrorist groups. Operations against by sea-users and maritime security providers, the USS Cole (2000) and the tanker Limburg lack of confidence by terrorist groups in the (2002), attributed to Al-Qaeda, are good success of major attacks against sea-based examples of maritime terrorism in the Arabian targets due to insufficient expertise and Peninsula, where small crafts laden with experienced militants for conducting such explosives have proven successful in causing operations. -

Floating Armories: a Legal Grey Area in Arms Trade and the Law of the Sea

FLOATING ARMORIES: A LEGAL GREY AREA IN ARMS TRADE AND THE LAW OF THE SEA BY ALEXIS WILPON* ABSTRACT In response to maritime piracy concerns, shippers often hire armed guards to protect their ships. However, due to national and international laws regarding arms trade, ships are often unable to dock in foreign ports with weapons and ammunition. As a response, floating armories operate as weapons and ammuni tion storage facilities in international waters. By operating solely in interna tional waters, floating armories avoid national and international laws regard ing arms trade. However, there is a significant lack of regulations governing floating armories, and this leads to serious safety concerns including lack of standardized weapon storage, lack of records documenting the transfer of weapons and ammunitions, and lack of regulation from flags of convenience. Further, there is no publically available registry of floating armories and so the number of floating armories operating alongside the quantity of arms and ammunition on board is unknown. This Note suggests several solutions that will increase the transparency and safety of floating armories. Such solutions include requirements that floating armory operators register their vessels only to states in which a legitimate relationship exists, minimum standards that operators must follow, and the creation of a publically available registry. Finally, it concludes by providing alternative mechanisms by which states may exercise jurisdiction over foreign vessels operating in the High Seas. I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 874 II. THE PROBLEM OF MARITIME PIRACY ..................... 877 III. HOW FLOATING ARMORIES OPERATE..................... 878 IV. FLOATING ARMORIES AND THE LEGAL GRAY AREA............ 880 A. The Lack of Laws and Regulations ................. -

Maritime Security in the Asia-Pacific

Asia Programme Meeting Summary Maritime Security in the Asia-Pacific 12 February 2015 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/ speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Maritime Security in the Asia-Pacific This is a summary of an event held at Chatham House on 12 February 2015, made up of a keynote speech by Ambassador Yoshiji Nogami and three sessions. At the first session, James Przystup, Ryo Sahashi and Sam Bateman discussed the main security challenges – traditional and non-traditional – in the Asia- Pacific. At the second session, Masayuki Masuda, Thang Nguyen Dang and Douglas Guilfoyle spoke about the rule of law in the region and how it can be upheld; and at the third session, Ren Xiao, Ambassador Rakesh Sood, Sir Anthony Dymock and Alessio Patalano extended the dialogue to beyond the Asia-Pacific. -

1 James Kraska

C URRICULUM V ITAE James Kraska Stockton Center for the Study of International Law United States Naval War College 686 Cushing Rd. Newport, RI 02841 (401) 841-1536 [email protected] Education S.J.D. University of Virginia School of Law LL.M. University of Virginia School of Law J.D. Indiana University Maurer School of Law M.A.I.S. School of Politics and Economic, Claremont Graduate School B.A. Mississippi State University, summa cum laude Professional Experience Present Chairman and Howard S. Levie Professor (Full professor with tenure) Stockton Center for the Study of International Law, U.S. Naval War College Fall 2017 Visiting Professor of Law and John Harvey Gregory Lecturer on World Organization, Harvard Law School 2013-14 Mary Derrickson McCurdy Visiting Scholar, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University 2008-13 Professor of Law, Stockton Center for the Study of International Law, U.S. Naval War College Fall 2012 Visiting Professor of Law, University of Maine School of Law 2007-08 Director, International Negotiations Division, Global Security Affairs, Joint Staff, Pentagon 2005-07 Oceans Law and Policy Adviser, Joint Staff, Pentagon 2002-05 Deputy Legal Adviser, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Plans, Policy and Operations, Pentagon 2001-02 International Law Adviser, Office of the Navy Judge Advocate General, Pentagon 1999-01 Legal Adviser, Expeditionary Strike Group Seven/Task Force 76, Japan 1996-99 Legal Adviser, Dep’t of Defense Joint Interagency Task Force West 1993-96 Criminal Trial Litigator, U.S. Naval Legal Service Office, Japan 1992-93 Post-Doctoral Fellow, Marine Policy Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution * 1993-2013, Judge Advocate General’s Corps, U.S. -

Iraq: Summary of U.S

Order Code RL31763 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Summary of U.S. Forces Updated March 14, 2005 Linwood B. Carter Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Summary of U.S. Forces Summary This report provides a summary estimate of military forces that have reportedly been deployed to and subsequently withdrawn from the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) Area of Responsibility (AOR), popularly called the Persian Gulf region, to support Operation Iraqi Freedom. For background information on the AOR, see [http://www.centcom.mil/aboutus/aor.htm]. Geographically, the USCENTCOM AOR stretches from the Horn of Africa to Central Asia. The information about military units that have been deployed and withdrawn is based on both official government public statements and estimates identified in selected news accounts. The statistics have been assembled from both Department of Defense (DOD) sources and open-source press reports. However, due to concerns about operational security, DOD is not routinely reporting the composition, size, or destination of units and military forces being deployed to the Persian Gulf. Consequently, not all has been officially confirmed. For further reading, see CRS Report RL31701, Iraq: U.S. Military Operations. This report will be updated as the situation continues to develop. Contents U.S. Forces.......................................................1 Military Units: Deployed/En Route/On Deployment Alert ..............1 -

D:\AN12034\Wholechapters\AN Chaps PDF.Vp

CHAPTER 1 MISSION AND HISTORY OF NAVAL AVIATION INTRODUCTION in maintaining command of the seas. Accomplishing this task takes five basic operations: Today's naval aircraft have come a long way from the Wright Brothers' flying machine. These modern 1. Eyes and ears of the fleet. Naval aviation has and complex aircraft require a maintenance team that is over-the-horizon surveillance equipment that provides far superior to those of the past. You have now joined vital information to our task force operation. this proud team. 2. Protection against submarine attack. Anti- You, the Airman Apprentice, will get a basic submarine warfare operations go on continuously for introduction to naval aviation from this training the task force and along our country's shoreline. This manual. In the Airman manual, you will learn about the type of mission includes hunter/killer operations to be history and organization of naval aviation; the design of sure of task force protection and to keep our coastal an aircraft, its systems, line operations, and support waterways safe. equipment requirements; and aviation safety, rescue, 3. Aid and support operations during amphibious crash, and fire fighting. landings. From the beginning to the end of the In this chapter, you will read about some of the operations, support occurs with a variety of firepower. historic events of naval aviation. Also, you will be Providing air cover and support is an important introduced to the Airman rate and different aviation function of naval aviation in modern, technical warfare. ratings in the Navy. You will find out about your duties 4. -

The Demand for Responsiveness in Past U.S. Military Operations for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N STACIE L. PETTYJOHN The Demand for Responsiveness in Past U.S. Military Operations For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR4280 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0657-6 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: U.S. Air Force/Airman 1st Class Gerald R. Willis. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The Department of Defense (DoD) is entering a period of great power competition at the same time that it is facing a difficult budget environment. -

Maritime Security: Potential Terrorist Attacks and Protection Priorities

Order Code RL33787 Maritime Security: Potential Terrorist Attacks and Protection Priorities Updated May 14, 2007 Paul W. Parfomak and John Frittelli Resources, Science, and Industry Division Maritime Security: Potential Terrorist Attacks and Protection Priorities Summary A key challenge for U.S. policy makers is prioritizing the nation’s maritime security activities among a virtually unlimited number of potential attack scenarios. While individual scenarios have distinct features, they may be characterized along five common dimensions: perpetrators, objectives, locations, targets, and tactics. In many cases, such scenarios have been identified as part of security preparedness exercises, security assessments, security grant administration, and policy debate. There are far more potential attack scenarios than likely ones, and far more than could be meaningfully addressed with limited counter-terrorism resources. There are a number of logical approaches to prioritizing maritime security activities. One approach is to emphasize diversity, devoting available counter- terrorism resources to a broadly representative sample of credible scenarios. Another approach is to focus counter-terrorism resources on only the scenarios of greatest concern based on overall risk, potential consequence, likelihood, or related metrics. U.S. maritime security agencies appear to have followed policies consistent with one or the other of these approaches in federally-supported port security exercises and grant programs. Legislators often appear to focus attention on a small number of potentially catastrophic scenarios. Clear perspectives on the nature and likelihood of specific types of maritime terrorist attacks are essential for prioritizing the nation’s maritime anti-terrorism activities. In practice, however, there has been considerable public debate about the likelihood of scenarios frequently given high priority by federal policy makers, such as nuclear or “dirty” bombs smuggled in shipping containers, liquefied natural gas (LNG) tanker attacks, and attacks on passenger ferries. -

Cyber-Attacks: a Digital Threat Reality Affecting the Maritime Industry

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 11-4-2018 Cyber-attacks: a digital threat reality affecting the maritime industry David Miranda Silgado Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Transportation Commons Recommended Citation Miranda Silgado, David, "Cyber-attacks: a digital threat reality affecting the maritime industry" (2018). World Maritime University Dissertations. 663. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/663 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden CYBER-ATTACKS; A DIGITAL THREAT REALITY AFFECTING THE MARITIME INDUSTRY By DAVID MIRANDA SILGADO Republic of Panamá A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In MARITIME AFFAIRS (MARITIME SAFETY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATION) 2018 © Copyright David Miranda Silgado, 2018 DECLARATION I certify that all the material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The contents of this dissertation -

Maritime Security: Perspectives for a Comprehensive Approach

ISPSW Strategy Series: Focus on Defense and International Security Issue Maritime Security – Perspectives for a Comprehensive Approach No. 222 Lutz Feldt, Dr. Peter Roell, Ralph D. Thiele Apr 2013 Maritime Security – Perspectives for a Comprehensive Approach Lutz Feldt, Dr. Peter Roell, Ralph D. Thiele April 2013 Abstract Challenges to “Maritime Security” have many faces – piracy and armed robbery, maritime terrorism, illicit traf- ficking by sea, i.e. narcotics trafficking, small arms and light weapons trafficking, human trafficking, global cli- mate change, cargo theft etc. These challenges keep evolving and may be hybrid in nature: an interconnected and unpredictable mix of traditional and irregular warfare, terrorism, and/or organized crime. In our study we focus on piracy, armed robbery and maritime terrorism. Starting with principle observations regarding Maritime Security and the threat situation, we have a look at operational requirements and maritime collaboration featuring Maritime Domain Awareness. Finally, we give recommendations for political, military and business decision makers. ISPSW The Institute for Strategic, Political, Security and Economic Consultancy (ISPSW) is a private institute for research and consultancy. The ISPSW is objective and task oriented and is above party politics. In an ever more complex international environment of globalized economic processes and worldwide political, ecological, social and cultural change, bringing major opportunities but also risks, decision-makers in enter- prises and politics depend more than ever before on the advice of highly qualified experts. ISPSW offers a range of services, including strategic analyses, security consultancy, executive coaching and intercultural competency. ISPSW publications examine a wide range of topics connected with politics, econo- my, international relations, and security/ defense. -

Maritime Security Issues in East Asia CNA Maritime Asia Project: Workshop Four

Maritime Security Issues in East Asia CNA Maritime Asia Project: Workshop Four Catherine K. Lea • Michael A. McDevitt DOP-2013-U-006034-Final September 2013 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “prob-lem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the follow-ing areas: • The full range of Asian security issues • The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf • Maritime strategy • Insurgency and stabilization • Future national security environment and forces • European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral • West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea • Latin America • The world’s most important navies • Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

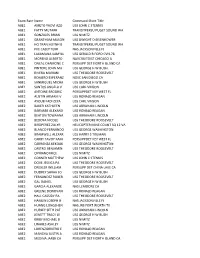

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE