Small Bowel Obstruction Acute Pancreatitis, Upper GI Bleeding, Acute Diverticulitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diverticular Abscess Presenting As a Strangulated Inguinal Hernia: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Ulster Med J 2007; 76 (2) 107-108 Presidential Address 107 Case Report Diverticular Abscess Presenting as a Strangulated Inguinal Hernia: Case Report and review of the literature. S Imran H Andrabi, Ashish Pitale*, Ahmed AS El-Hakeem Accepted 22 December 2006 ABSTRACT noted nausea, anorexia and increasing abdominal pain. She had no previous history of any surgery or trauma and was on Potentially life threatening diseases can mimic a groin hernia. warfarin for atrial fibrillation. We present an unusual case of diverticulitis with perforation and a resulting abscess presenting as a strangulated inguinal hernia. The features demonstrated were not due to strangulation of the contents of the hernia but rather pus tracking into the hernia sac from the peritoneal cavity. The patient underwent sigmoid resection and drainage of retroperitoneal and pericolonic abscesses. Radiological and laboratory studies augment in reaching a diagnosis. The differential diagnosis of inguinal swellings is discussed. Key Words: Diverticulitis, diverticular perforation, diverticular abscess, inguinal hernia INTRODUCTION The association of complicated inguinal hernia and diverticulitis is rare1. Diverticulitis can present as left iliac fossa pain, rectal bleeding, fistulas, perforation, bowel obstruction and abscesses. Our patient presented with a diverticular perforation resulting in an abscess tracking into the inguinal canal and clinically masquerading as a Fig 2. CT scan showing inflammatory changes with strangulated inguinal hernia. The management warranted an stranding of the subcutaneous fat in the left groin and a exploratory laparotomy and drainage of pus. large bowel diverticulum CASE REPORT On admission, she had a tachycardia (pulse 102 beats/min) and a temperature of 37.5OC. -

MANAGEMENT of ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN Patrick Mcgonagill, MD, FACS 4/7/21 DISCLOSURES

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN Patrick McGonagill, MD, FACS 4/7/21 DISCLOSURES • I have no pertinent conflicts of interest to disclose OBJECTIVES • Define the pathophysiology of abdominal pain • Identify specific patterns of abdominal pain on history and physical examination that suggest common surgical problems • Explore indications for imaging and escalation of care ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (1) HISTORICAL VIGNETTE (2) • “The general rule can be laid down that the majority of severe abdominal pains that ensue in patients who have been previously fairly well, and that last as long as six hours, are caused by conditions of surgical import.” ~Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen, 21st ed. BASIC PRINCIPLES OF THE DIAGNOSIS AND SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF ABDOMINAL PAIN • Listen to your (and the patient’s) gut. A well honed “Spidey Sense” will get you far. • Management of intraabdominal surgical problems are time sensitive • Narcotics will not mask peritonitis • Urgent need for surgery often will depend on vitals and hemodynamics • If in doubt, reach out to your friendly neighborhood surgeon. Septic Pain Sepsis Death Shock PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ABDOMINAL PAIN VISCERAL PAIN • Severe distension or strong contraction of intraabdominal structure • Poorly localized • Typically occurs in the midline of the abdomen • Seems to follow an embryological pattern • Foregut – epigastrium • Midgut – periumbilical • Hindgut – suprapubic/pelvic/lower back PARIETAL/SOMATIC PAIN • Caused by direct stimulation/irritation of parietal peritoneum • Leads to localized -

Diverticulitis of the Appendix

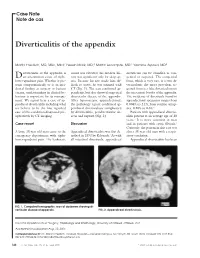

Case Note Note de cas Diverticulitis of the appendix Martin Friedlich, MD, MSc, MEd;* Neesh Malik, MD;† Martin Lecompte, MD;† Yasmine Ayroud, MD‡ iverticulitis of the appendix is count was elevated; his medical his- diverticula can be classified as con- Dan uncommon cause of right- tory was significant only for sleep ap- genital or acquired. The congenital lower-quadrant pain. Whether it pre- nea. Because his size made him dif- form, which is very rare, is a true di- sents symptomatically or is an inci- ficult to assess, he was scanned with verticulum; the more prevalent ac- dental finding at surgery or barium CT (Fig. 1). The scan confirmed ap- quired form is a false diverticulum on enema, understanding its clinical be- pendicitis, but also showed suspected the mesenteric border of the appendix. haviour is important for its manage- diverticular disease of the appendix. The incidence of diverticula found in ment. We report here a case of ap- After laparoscopic appendectomy, appendectomy specimens ranges from pendiceal diverticulitis including what the pathology report confirmed ap- 0.004% to 2.1%; from routine autop- we believe to be the first reported pendiceal diverticulosis complicated sies, 0.20% to 0.6%.2 case of this condition diagnosed pre- by diverticulitis, peridiverticular ab- Patients with appendiceal divertic- operatively by CT imaging. scess and rupture (Fig. 2). ulitis present at an average age of 38 years.3 It is more common in men Case report Discussion and in patients with cystic fibrosis.2 Curiously, the patient in this case was A large 38-year-old man came to the Appendiceal diverticulitis was first de- also a 38-year-old man with a respir- emergency department with right- scribed in 1893 by Kelynack.1 As with atory condition. -

Colonic Gallstone Obstruction

Advances in Clinical Medical Research and Healthcare Delivery Volume 1 Issue 1 Inaugural Issue Article 4 2021 Colonic Gallstone Obstruction Abdoulaziz Toure M.D Arnot Ogden Medical Center, [email protected] Mitchell Witkowski LECOM, [email protected] Vithal Vernenkar D.O Newark Wayne Community Hospital, [email protected] Brian Watkins MD, MS, FACS Newark Wayne Community Hospital, [email protected] Prasad V. Penmetsa M.D Rochester General Hospital, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rochesterregional.org/advances Part of the Health and Medical Administration Commons, Medical Education Commons, and the Medical Specialties Commons Recommended Citation Toure A, Witkowski M, Vernenkar V, Watkins B, Penmetsa PV. Colonic Gallstone Obstruction. Advances in Clinical Medical Research and Healthcare Delivery. 2021; 1(1). doi: 10.53785/2769-2779.1005. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by RocScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Advances in Clinical Medical Research and Healthcare Delivery by an authorized editor of RocScholar. ISSN: 2769-2779 Colonic Gallstone Obstruction Abstract This report discusses a case of a 79-year-old Caucasian female who presented with large bowel obstruction. A significant TC findings of cholecystocolic fistula and an impacted gallstone at the junction of the descending and sigmoid colon. We present a case of colonic gallstone obstruction that was treated with endoscopic lithotripsy. This interventional approach is effective in stable elderly patients with high surgical risk and in patients with significant comorbidities. Keywords gallstone complication, Cholecystocolic fistula, colonic gallstones, large bowel gallstones, gallstone ileus This article is available in Advances in Clinical Medical Research and Healthcare Delivery: https://scholar.rochesterregional.org/advances/vol1/iss1/4 Toure et al.: Colonic Gallstone Obstruction Background Gallstone ileus is a rare complication of cholelithiasis. -

Gallstone Ileus Treated by Incidental Meckel's Diverticulectomy

Open Access Case Report DOI: 10.7759/cureus.14078 Gallstone Ileus Treated by Incidental Meckel’s Diverticulectomy Zachary A. Koenig 1 , Jason Turner 2 1. School of Medicine, West Virginia University, Morgantown, USA 2. Department of Surgery, West Virginia University, Martinsburg, USA Corresponding author: Zachary A. Koenig, [email protected] Abstract Gallstone ileus is an uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction in the elderly. It is typically recognized on computed tomography by the presence of pneumobilia and a gallstone in the right iliac fossa. Nonetheless, it is important to consider that gallstone ileus may represent the presentation of another pathology rather than an entity on its own. Here, we report successful retrieval of a gallstone that was causing ileus. Intraoperatively, the gallstone was noted lodged in the terminal ileum distal to an incidentally noted Meckel’s diverticulum. The gallstone was milked proximally into the Meckel’s diverticulum and the base was transected. This case illustrates a rare, but unique, surgical technique utilizing a small bowel diverticulum as a vector for stone removal. Categories: Gastroenterology, General Surgery Keywords: gallstone ileus, meckel's diverticulum, diverticulectomy Introduction Meckel’s diverticulum is a true diverticulum that arises from the antimesenteric surface of the middle-to- distal ileum due to incomplete obliteration of the vitelline duct during the seventh week of gestation. It is the most common malformation of the gastrointestinal tract [1]. The anomaly is known for its “rule of twos,” being present in 2% of the population, presenting before the age of two, being twice as common in men compared to women, and being located two feet from the ileocecal valve [2]. -

Diverticulitis

Information O from Your Family Doctor Diverticulitis What is diverticulosis? How is it treated? Diverticulosis (di-ver-tik-u-LO-sis) is when If you have mild diverticulitis, your doctor may you have pouches in the colon that bulge out. send you home. You should not eat and should These pouches are called diverticula (di-ver- drink only clear liquids. Then, in two or three TIK-u-lah). They are caused by pressure in the days, you should go back to see your doctor. colon that weakens the bowel wall. Not eating Some patients may also need antibiotics. If you enough fiber, not exercising enough, and taking have moderate or severe diverticulitis, you may nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like need to stay in the hospital for IV antibiotics. ibuprofen can cause diverticulosis. Will I need a colonoscopy? What is diverticulitis? Most people will not need one. But, if you have Diverticulitis (di-ver-tik-u-LI-tis) is when severe diverticulitis, your doctor may tell you to diverticula are inflamed or infected. One get a colonoscopy four to six weeks after your in four people with diverticulosis will get symptoms have gone away. diverticulitis. Will I need surgery? What are the symptoms? Most people do not need surgery. Symptoms vary and can include stomach pain (usually on the left side), fever, constipation or Can diverticulitis come back? diarrhea, and nausea. Yes, but in most people (nine out of 10), diverticulitis does not come back. You can How is it diagnosed? decrease your chances of getting diverticulitis Your doctor will ask you questions about your again by eating a lot of fiber. -

Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis

Information for Behavioral Health Providers in Primary Care Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis What are Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis? Many people have small pouches in their colons that bulge outward through weak spots, like an inner tube that pokes through weak places in a tire. Each pouch is called a diverticulum. Pouches (plural) are called diverticula. The condition of having diverticula is called diverticulosis. About 10 percent of Americans over the age of 40 have diverticulosis. The condition becomes more common as people age. About half of all people over the age of 60 have diverticulosis. When the pouches become infected or inflamed, the condition is called diverticulitis. This happens in 10 to 25 percent of people with diverticulosis. Diverticulosis and diverticulitis are also called diverticular disease. What are the symptoms? Diverticulosis Most people with diverticulosis do not have any discomfort or symptoms. However, symptoms may include mild cramps, bloating, and constipation. Other diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and stomach ulcers cause similar problems, so these symptoms do not always mean a person has diverticulosis. You should visit your doctor if you have these troubling symptoms. Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis (continued) Diverticulitis The most common symptom of diverticulitis is abdominal pain. The most common sign is tenderness around the left side of the lower abdomen. If infection is the cause, fever, nausea, vomiting, chills, cramping, and constipation may occur as well. The severity of symptoms depends on the extent of the infection and complications. What are the complications? Diverticulitis can lead to bleeding, infections, perforations or tears, or blockages. These complications always require treatment to prevent them from progressing and causing serious illness. -

Best Practices in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diverticulitis And

AHRQ Safety Program for Improving Antibiotic Use 1 Best Practices in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diverticulitis and Biliary Tract Infections Acute Care Slide Title and Commentary Slide Number and Slide Best Practices in the Diagnosis and Acute CareSlide 1 Treatment of Diverticulitis and Biliary Tract Infections Acute Care SAY: This presentation will address two common intra- abdominal infections: diverticulitis and biliary tract infections. Objectives Slide 2 SAY: The objectives for this presentation are to: Describe the approach to the diagnosis of diverticulitis and biliary tract infections Identify options for empiric antibiotic therapy for diverticulitis and biliary tract infections Discuss the importance of source control in the management of intra-abdominal infections Identify options for antibiotic therapy for diverticulitis and biliary tract infections after additional clinical data are known Describe the optimal duration of therapy for diverticulitis and biliary tract infections AHRQ Pub. No. 17(20)-0028-EF November 2019 Slide Title and Commentary Slide Number and Slide Diverticulitis Slide 3 SAY: We will start by discussing diverticulitis. The Four Moments of Antibiotic Decision Slide 4 Making SAY: We will review diverticulitis using the Four Moments of Antibiotic Decision Making. 1. Does my patient have an infection that requires antibiotics? 2. Have I ordered appropriate cultures before starting antibiotics? What empiric therapy should I initiate? 3. A day or more has passed. Can I stop antibiotics? Can I narrow therapy -

Acute Sigmoid Colon Diverticulitis Axial CECT Image Shows Inflamed Sigmoid Colon Diverticula with Adjacent Stranding and Edema

66-year-old male with fever and bilateral lower quadrant abdominal pain Joseph Ryan, MS4 Edward Gillis, MD David Karimeddini, MD ? Acute sigmoid colon diverticulitis Axial CECT image shows inflamed sigmoid colon diverticula with adjacent stranding and edema. Coronal CECT images demonstrating inflamed sigmoid colon diverticula with adjacent stranding and edema. Background • Colonic diverticula are sac-like protrusions of the colon wall – mucosa pushing through muscular layer defects (as opposed to outpouching of all layers) – Associated with increased intraluminal pressures • Diverticulosis describes the presence of multiple diverticula – Predominantly left-sided in the Western hemisphere – Prevalence rates of 5 to 45%; most commonly seen in elderly • Diverticulitis is inflammation in the setting of diverticulosis, usually due to fecalith obstruction and infection leading to micro- or macro-perforation of a diverticulum – Occurs in ~4% of patients with diverticulosis – Acute complications occur in ~25% of patients • Complications can include bowel obstruction, abscess formation, peritonitis and fistula formation Diagnosis • Patients typically present with lower abdominal pain and tenderness – Left-sided in ~85% of cases; often gradually becomes more generalized • Symptoms resemble “left-sided appendicitis” – Other symptoms can include fever, nausea, vomiting, constipation and diarrhea – Peritoneal signs and palpable mass (“inflammatory phlegmon”) may be present – May have a mild leukocytosis (~55%) • CT is the imaging modality of choice -

Diverticular Disease-Related Colitis

Diverticular Disease-Related Colitis KEY FACTS Colon TERMINOLOGY ○ Abscess, fistula, perforation • Segmental colitis-associated diverticulosis (SCAD) ○ Exception is Crohn disease-like variant of SCAD that may show mural lymphoid aggregates ETIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS MICROSCOPIC • Unknown, TNF-α may play role • Chronic colitis-like changes mimicking inflammatory bowel CLINICAL ISSUES disease • Presents with hematochezia, abdominal pain, diarrhea • Ulcerative colitis-like variant shows changes confined to • Median age: 64 years mucosa ○ Range: 40-86 years ○ Diverticulitis may or may not be present in these cases • Predominately involves descending and sigmoid colon (with • Crohn disease-like variant shows mural lymphoid rectal sparing) aggregates • Treatment directed toward diverticular disease suppresses • Changes in both variants confined to segment involved symptoms with diverticulosis coli MACROSCOPIC TOP DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES • Mucosal changes are mild and nonspecific • Ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, infectious colitis, diversion • Mural changes are related more to underlying diverticulosis colitis, NSAID-associated colitis coli rather than SCAD Diverticular Disease-Associated Colitis Diverticular Disease-Associated Colitis (Left) The mucosa surrounding the openings of diverticula ſt into the colonic lumen is erythematous and granular, consistent with diverticular disease-associated colitis (DDAC) . (Right) It is not uncommon to find some inflammation or erosions around the luminal opening of a colonic diverticulum ſt. To be diagnostic of DDAC, inflammation must involve the mucosa in the interdiverticular region . Chronic Active Colitis Basal Lymphoplasmacytosis (Left) A chronic colitis pattern of inflammatory infiltrate is seen in both the ulcerative colitis-like and Crohn disease- like variant of DDAC. The mucosal changes are indistinguishable from true inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). (Right) A band of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is present beneath the base of the crypts in the mucosa. -

Perforated Sigmoid Diverticulitis in a Lumbar Hernia After

Frueh et al. BMC Surgery 2014, 14:46 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2482/14/46 CASE REPORT Open Access Perforated sigmoid diverticulitis in a lumbar hernia after iliac crest bone graft - a case report Florian S Frueh1,2†, Raphael N Vuille-dit-Bille1,3†, Dimitri A Raptis4, Hanspeter Notter1* and Brigitte S Muff1 Abstract Background: The combination of perforated diverticulitis in a lumbar hernia constitutes an extremely rare condition. Case presentation: We report a case of a 66 year old Caucasian woman presenting with perforated sigmoid diverticulitis localized in a lumbar hernia following iliac crest bone graft performed 18 years ago. Emergency treatment consisted of laparoscopic peritoneal lavage. Elective sigmoid resection was scheduled four months later. At the same time a laparoscopic hernia repair with a biologic mesh graft was performed. Conclusion: This case shows a very seldom clinical presentation of lumbar hernia. Secondary colonic resection and concurrent hernia repair with a biologic implant have proven useful in treating this rare condition. Keywords: Perforated diverticulitis, Lumbar hernia, Iliac crest bone graft, Laparoscopic hernia repair, Mesh Background Here, we describe an extremely rare combination of Complicated diverticulitis may be classified according to perforated diverticulitis in a lumbar hernia. Hinchey into four stages [1] (Table 1). Treatment of per- forated diverticulitis with peritonitis is a source of con- Case presentation troversy [2]. Patients with purulent or fecal peritonitis A 66 year-old female Caucasian patient (BMI 26.4 kg/m2) ’ corresponding to Hinchey III and IV require Hartmann s presented with a one-week history of lower left abdominal procedure (i.e. -

Acute Colonic Diverticulitis

Annals of Internal Medicineᮋ In the Clinic® Acute Colonic Diverticulitis Diagnosis cute colonic diverticulitis is a gastrointes- tinal condition frequently encountered Aby primary care practitioners, hospital- Treatment ists, surgeons, and gastroenterologists. Clinical presentation ranges from mild abdominal pain to peritonitis with sepsis. It can often be diag- Practice Improvement nosed on the basis of clinical features alone, but imaging is necessary in more severe presenta- tions to rule out such complications as abscess and perforation. Treatment depends on the se- verity of the presentation, presence of compli- cations, and underlying comorbid conditions. Medical and surgical treatment algorithms are evolving. This article provides an evidence- based, clinically relevant overview of the epide- miology, diagnosis, and treatment of acute diverticulitis. CME/MOC activity available at Annals.org. Physician Writers doi:10.7326/AITC201805010 Sophia M. Swanson, MD Lisa L. Strate, MD, MPH CME Objective: To review current evidence for diagnosis, treatment, and practice From the University of improvement of acute colonic diverticulitis. Washington School of Funding Source: American College of Physicians. Medicine, Seattle, Washington. Disclosures: Dr. Swanson, ACP Contributing Author, has disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Strate, ACP Contributing Author, reports grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje /ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M18-0023. With the assistance of additional physician writers, the editors of Annals of Internal Medi- cine develop In the Clinic using MKSAP and other resources of the American College of Physicians. In the Clinic does not necessarily represent official ACP clinical policy.