Genetic Testing Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viewed Under 23 (B) Or 203 (C) fi M M Male Cko Mice, and Largely Unaffected Magni Cation; Scale Bars, 500 M (B) and 50 M (C)

BRIEF COMMUNICATION www.jasn.org Renal Fanconi Syndrome and Hypophosphatemic Rickets in the Absence of Xenotropic and Polytropic Retroviral Receptor in the Nephron Camille Ansermet,* Matthias B. Moor,* Gabriel Centeno,* Muriel Auberson,* † † ‡ Dorothy Zhang Hu, Roland Baron, Svetlana Nikolaeva,* Barbara Haenzi,* | Natalya Katanaeva,* Ivan Gautschi,* Vladimir Katanaev,*§ Samuel Rotman, Robert Koesters,¶ †† Laurent Schild,* Sylvain Pradervand,** Olivier Bonny,* and Dmitri Firsov* BRIEF COMMUNICATION *Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology and **Genomic Technologies Facility, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; †Department of Oral Medicine, Infection, and Immunity, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; ‡Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry, St. Petersburg, Russia; §School of Biomedicine, Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia; |Services of Pathology and ††Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University Hospital of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; and ¶Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France ABSTRACT Tight control of extracellular and intracellular inorganic phosphate (Pi) levels is crit- leaves.4 Most recently, Legati et al. have ical to most biochemical and physiologic processes. Urinary Pi is freely filtered at the shown an association between genetic kidney glomerulus and is reabsorbed in the renal tubule by the action of the apical polymorphisms in Xpr1 and primary fa- sodium-dependent phosphate transporters, NaPi-IIa/NaPi-IIc/Pit2. However, the milial brain calcification disorder.5 How- molecular identity of the protein(s) participating in the basolateral Pi efflux remains ever, the role of XPR1 in the maintenance unknown. Evidence has suggested that xenotropic and polytropic retroviral recep- of Pi homeostasis remains unknown. Here, tor 1 (XPR1) might be involved in this process. Here, we show that conditional in- we addressed this issue in mice deficient for activation of Xpr1 in the renal tubule in mice resulted in impaired renal Pi Xpr1 in the nephron. -

Increased Nuchal Translucency Precision Panel

Increased Nuchal Translucency Precision Panel Overview Increased Nuchal Translucency (NT) is defined as an abnormal accumulation of fluid in the nuchal area, which is visualized as a thickened sonolucent area. It is a standardized measure obtained between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation to calculate the risk of a fetus being affected by a chromosomal aneuploidy. NT>3.5mm has been found to be associated with fetal chromosomal abnormalities and single-gene disorders as well as cardiac defects and other structural abnormalities in euploid and aneuploid fetuses. Proportionally as NT increases, even with a normal karyotype, there is a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage, intrauterine death, congenital heart defects and numerous other structural and genetic syndromes. There is not one single cause of increased NT, it is based on a complex and multifactorial process, linked to one or more embryonic processes. It has been shown that a persistently increased NT with a normal karyotype and aCGH has a 4-10% probability of being associated to Noonan Syndrome and/or other RASopathies using Whole Exome Sequencing (WES). However, the general tendency following detection of isolated enlarged NT in an euploid fetus is that most babies with normal detailed ultrasound examination and echocardiography will have uneventful outcomes. The Igenomix Increased Nuchal Translucency Precision Panel can be used to make a directed and accurate prenatal differential diagnosis of increased nuchal translucency in patients with or without a normal karyotype ultimately leading to a better management and prognosis of the associated comorbidities. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the genes involved in this disease using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to fully understand the spectrum of relevant genes involved. -

Tfr2, Hfe, and Hjv in the Regulation of Body Iron Homeostasis

TFR2, HFE, AND HJV IN THE REGULATION OF BODY IRON HOMEOSTASIS By Christal Anna Worthen A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Cell & Developmental Biology and the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 School of Medicine Oregon Health & Science University CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ___________________________________ This is to certify that the PhD dissertation of Christal A Worthen has been approved ______________________________________ Caroline Enns, Ph.D., mentor ______________________________________ Peter Mayinger, Ph.D., Chairman ______________________________________ Philip Stork, M.D. ______________________________________ David Koeller, M.D. ______________________________________ Alex Nechiporuk, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS i List of Figures ii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations v Abstract: 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 5 Abstract and Introduction 6 Binding partners, regulation, and trafficking of TFR2 9 Disease-causing mutations in TFR2 12 Hepcidin regulation 12 Physiological function of TFR2 15 Current TFR2 models 18 Summary 19 Figure 21 Chapter 2: The cytoplasmic domain of TFR2 is necessary for 22 HFE, HJV, and TFR2 regulation of hepcidin Abstract 23 Capsule & Introduction 24 Materials and Methods 26 Results 32 Figures 41 Discussion 49 Chapter 3: Lack of functional TFR2 results in stress erythropoiesis 53 Introduction 54 Materials and Methods 55 Results 57 Figures 60 Discussion 65 Chapter 4: Conclusions and future directions 67 Appendices Appendix A: Coculture of HepG2 cells reduces hepcidin expression 71 Appendix B: Hfe-/- macrophages handle iron differently 80 Appendix C: Both ZIP14A and ZIP14B are regulated by HFE and iron 91 Appendix D: The cytoplasmic domain of HFE does not interact with 99 ZIP14 loop 2 by yeast-2-hybris References 105 i LIST OF FIGURES Figure Abstract 1: Body iron homeostasis. -

2013 New Molecular CPT Co

Cleveland Clinic Laboratories 2013 New Molecular CPT Codes 2013 Test Name Order Code Billing Code CPT Codes 2012 CPT Codes ACADM PCR, Complete, Tier 2 ACADM 88175 81404 83891, 83894x10, 83898x10, 83904x20 ACTA2 Gene Sequencing ACTA2 88528 81403 83898x9, 83904x9, 83891 ADmark ApoE Genotype (Symptomatic) APOALZ 82397 81401 83892, 83894, 83898, 81401, 83891 ADmark PS-1 Analysis, Symptomatic PS1SY 83019 81405 83904x10, 83909x10, 83898x10, 83891 Alpha Globin (HBA1 and HBA2) Sequencing HBA12 88847 81257 New test in 2013 Alpha Thalassemia Gene Deletion ATHAL 84123 81257 83891, 83900, 83901x8, 83894 Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Quantitation and Phenotyping PHA1A 84187 81332 82103, 82104 Angelman UBE3A Sequencing UBE3A 88200 81331 83898x8, 83904x10, 83909x10 APO E Genotype APOEG 79374 81401 83891, 81401, 83898, 83896x2 ARX Sequence Analysis ARXSEQ 87860 81404 83890, 83898x5, 83894, 83904x6 Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Evaluation AIRE 83293 81479 83909x14, 83891, 83898x14, 83904x14 Autosomal Dom Ataxia Evaluation AUTOAT 82179 81401, 83909x88, 83898x88, 83904x77, 81479x13 83891 Barth Syndrome, Carrier BARCAR 82536 81406 83891, 83898, 83904x2 Barth Syndrome, Initial Patient BARINI 82535 81406 83891, 83898, 83904x9 Bartonella PCR, Tissue TBART 87924 87471 83898x4, 83890, 83894 B-Cell Clonality Using BIOMED-2 PCR Primers BCBMD 87904 81261, 83891, 83900, 83909x5, 83898x3, 83901x2, 81264 83912, 81261, 81264 BCL 2 mbr (PCR) BCL2 81099 81401 81401, 83890, 83898, 83894, 83912 BCR/ABL Kinase Domain Mutation Analysis KINASE 84529 81403 83891, 83898, 83902, 83904x4, -

Blueprint Genetics Craniosynostosis Panel

Craniosynostosis Panel Test code: MA2901 Is a 38 gene panel that includes assessment of non-coding variants. Is ideal for patients with craniosynostosis. About Craniosynostosis Craniosynostosis is defined as the premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures leading to secondary distortion of skull shape. It may result from a primary defect of ossification (primary craniosynostosis) or, more commonly, from a failure of brain growth (secondary craniosynostosis). Premature closure of the sutures (fibrous joints) causes the pressure inside of the head to increase and the skull or facial bones to change from a normal, symmetrical appearance resulting in skull deformities with a variable presentation. Craniosynostosis may occur in an isolated setting or as part of a syndrome with a variety of inheritance patterns and reccurrence risks. Craniosynostosis occurs in 1/2,200 live births. Availability 4 weeks Gene Set Description Genes in the Craniosynostosis Panel and their clinical significance Gene Associated phenotypes Inheritance ClinVar HGMD ALPL Odontohypophosphatasia, Hypophosphatasia perinatal lethal, AD/AR 78 291 infantile, juvenile and adult forms ALX3 Frontonasal dysplasia type 1 AR 8 8 ALX4 Frontonasal dysplasia type 2, Parietal foramina AD/AR 15 24 BMP4 Microphthalmia, syndromic, Orofacial cleft AD 8 39 CDC45 Meier-Gorlin syndrome 7 AR 10 19 EDNRB Hirschsprung disease, ABCD syndrome, Waardenburg syndrome AD/AR 12 66 EFNB1 Craniofrontonasal dysplasia XL 28 116 ERF Craniosynostosis 4 AD 17 16 ESCO2 SC phocomelia syndrome, Roberts syndrome -

Pathological Relationships Involving Iron and Myelin May Constitute a Shared Mechanism Linking Various Rare and Common Brain Diseases

Rare Diseases ISSN: (Print) 2167-5511 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/krad20 Pathological relationships involving iron and myelin may constitute a shared mechanism linking various rare and common brain diseases Moones Heidari, Sam H. Gerami, Brianna Bassett, Ross M. Graham, Anita C.G. Chua, Ritambhara Aryal, Michael J. House, Joanna F. Collingwood, Conceição Bettencourt, Henry Houlden, Mina Ryten , John K. Olynyk, Debbie Trinder, Daniel M. Johnstone & Elizabeth A. Milward To cite this article: Moones Heidari, Sam H. Gerami, Brianna Bassett, Ross M. Graham, Anita C.G. Chua, Ritambhara Aryal, Michael J. House, Joanna F. Collingwood, Conceição Bettencourt, Henry Houlden, Mina Ryten , John K. Olynyk, Debbie Trinder, Daniel M. Johnstone & Elizabeth A. Milward (2016) Pathological relationships involving iron and myelin may constitute a shared mechanism linking various rare and common brain diseases, Rare Diseases, 4:1, e1198458, DOI: 10.1080/21675511.2016.1198458 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21675511.2016.1198458 © 2016 The Author(s). Published with View supplementary material license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC© Moones Heidari, Sam H. Gerami, Brianna Bassett, Ross M. Graham, Anita C.G. Chua, Ritambhara Aryal, Michael J. House, Joanna Accepted author version posted online: 22 Submit your article to this journal JunF. Collingwood, 2016. Conceição Bettencourt, PublishedHenry Houlden, online: Mina 22 Jun Ryten, 2016. for the UK Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC), John K. Olynyk, Debbie Trinder, Daniel M. Johnstone,Article views: and 541 Elizabeth A. Milward. View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=krad20 Download by: [University of Newcastle, Australia] Date: 17 May 2017, At: 19:57 RARE DISEASES 2016, VOL. -

Medical Genetics and Genomic Medicine in the United States of America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by George Washington University: Health Sciences Research Commons (HSRC) Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University Health Sciences Research Commons Pediatrics Faculty Publications Pediatrics 7-1-2017 Medical genetics and genomic medicine in the United States of America. Part 1: history, demographics, legislation, and burden of disease. Carlos R Ferreira George Washington University Debra S Regier George Washington University Donald W Hadley P Suzanne Hart Maximilian Muenke Follow this and additional works at: https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/smhs_peds_facpubs Part of the Genetics and Genomics Commons APA Citation Ferreira, C., Regier, D., Hadley, D., Hart, P., & Muenke, M. (2017). Medical genetics and genomic medicine in the United States of America. Part 1: history, demographics, legislation, and burden of disease.. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Medicine, 5 (4). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.318 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Pediatrics at Health Sciences Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pediatrics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Health Sciences Research Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENETICS AND GENOMIC MEDICINE AROUND THE WORLD Medical genetics and genomic medicine in the United States of America. Part 1: history, demographics, legislation, and burden of disease Carlos R. Ferreira1,2 , Debra S. Regier2, Donald W. Hadley1, P. Suzanne Hart1 & Maximilian Muenke1 1National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 2Rare Disease Institute, Children’s National Health System, Washington, District of Columbia Correspondence Carlos R. -

Post-Transcriptional Regulation of Hfe Gene Expression

RUTE ISABEL PAULO MARTINS POST-TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION OF HFE GENE EXPRESSION LISBOA 2010 nº de arquivo “copyright” RUTE ISABEL PAULO MARTINS POST-TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION OF HFE GENE EXPRESSION Thesis presented to obtain the Ph.D. degree in Biology (Molecular Genetics), by the Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia. LISBOA 2010 Agradecimentos Agradecimentos Ao concluir este trabalho gostaria de expressar o meu reconhecimento a todos aqueles que de algum modo contribuíram para a sua concretização. Esta tese de Doutoramento é o resultado de um trabalho de investigação realizado no Departamento de Genética do Instituto Nacional de Saúde Dr. Ricardo Jorge (INSA), em Lisboa, entre Janeiro de 2006 a Dezembro de 2009, onde foram disponibilizadas as condições essenciais para o seu desenvolvimento. Ao Presidente do Conselho Directivo do INSA, Professor Doutor José Pereira Miguel, manifesto o meu apreço. Agradeço à Doutora Maria Guida Boavida e ao Doutor João Lavinha por me terem recebido no então Centro de Genética Humana, permitindo a realização do meu trabalho, e por todo o interesse que demonstraram pelo mesmo. Este trabalho foi, na sua maioria, financiado pela Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia no âmbito do projecto de investigação PTDC/SAU/GMG/64494/2006, através do Programa de Financiamento Plurianual do Centro de Investigação em Genética Molecular Humana e sob a forma de uma Bolsa de Doutoramento com a referência SFRH/BD/21340/2005. À minha orientadora Doutora Paula Faustino estou reconhecida pela oportunidade inicial de me integrar no seu grupo de investigação, cujo acompanhamento ao longo destes oito anos tem sido crucial para a minha formação enquanto cientista. -

The Role of DMT1, Ferritin, and Transferrin Receptor in Schwann Cell Maturation and Myelination

9940 • The Journal of Neuroscience, December 11, 2019 • 39(50):9940–9953 Cellular/Molecular Iron Metabolism in the Peripheral Nervous System: The Role of DMT1, Ferritin, and Transferrin Receptor in Schwann Cell Maturation and Myelination X Diara A. Santiago Gonza´lez,* XVeronica T. Cheli,* Rensheng Wan, and XPablo M. Paez Hunter James Kelly Research Institute, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York 14203 Iron is an essential cofactor for many cellular enzymes involved in myelin synthesis, and iron homeostasis unbalance is a central component of peripheral neuropathies. However, iron absorption and management in the PNS are poorly understood. To study iron metabolism in Schwann cells (SCs), we have created 3 inducible conditional KO mice in which three essential proteins implicated in iron uptake and storage, the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), the ferritin heavy chain (Fth), and the transferrin receptor 1 (Tfr1), were postnatally ablated specifically in SCs. Deleting DMT1, Fth, or Tfr1 in vitro significantly reduce SC proliferation, maturation, and the myelination of DRG axons. This was accompanied by an important reduction in iron incorporation and storage. When these proteins were KO in vivo during the first postnatal week, the sciatic nerve of all 3 conditional KO animals displayed a significant reduction in the synthesis of myelin proteins and in the percentage of myelinated axons. Knocking out Fth produced the most severe phenotype, followed by DMT1 and, last, Tfr1. Importantly, DMT1 as well as Fth KO mice showed substantial motor coordination deficits. In contrast, deleting these proteins in mature myelinating SCs results in milder phenotypes characterized by small reductions in the percentage of myelinated axons and minor changes in the g-ratio of myelinated axons. -

HFE Hemochromatosis Testing

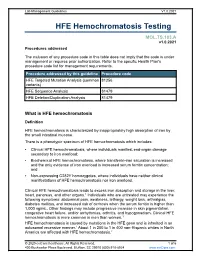

Lab Management Guidelines V1.0.2021 HFE Hemochromatosis Testing MOL.TS.183.A v1.0.2021 Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedure addressed by this guideline Procedure code HFE Targeted Mutation Analysis (common 81256 variants) HFE Sequence Analysis 81479 HFE Deletion/Duplication Analysis 81479 What is HFE hemochromatosis Definition HFE hemochromatosis is characterized by inappropriately high absorption of iron by the small intestinal mucosa. There is a phenotypic spectrum of HFE hemochromatosis which includes: Clinical HFE hemochromatosis, where individuals manifest end-organ damage secondary to iron overload; Biochemical HFE hemochromatosis, where transferrin-iron saturation is increased and the only evidence of iron overload is increased serum ferritin concentration; and Non-expressing C282Y homozygotes, where individuals have neither clinical manifestations of HFE hemochromatosis nor iron overload. Clinical HFE hemochromatosis leads to excess iron absorption and storage in the liver, heart, pancreas, and other organs.1 Individuals who are untreated may experience the following symptoms: abdominal pain, weakness, lethargy, weight loss, arthralgias, diabetes mellitus, and increased risk of cirrhosis when the serum ferritin is higher than 1,000 ng/mL. Other findings may include progressive increase in skin pigmentation, congestive heart failure, and/or arrhythmias, arthritis, and hypogonadism. Clinical HFE hemochromatosis is more common in men than women.1 HFE hemochromatosis is caused by mutations in the HFE gene and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.1 About 1 in 200 to 1 in 400 non-Hispanic whites in North America are affected with HFE hemochromatosis.2 © 2020 eviCore healthcare. -

81993354.Pdf

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1792 (2009) 112–121 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biochimica et Biophysica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bbadis Characterization of the first FGFRL1 mutation identified in a craniosynostosis patient Thorsten Rieckmann a, Lei Zhuang a, Christa E. Flück a,b, Beat Trueb a,c,⁎ a Department of Clinical Research, University of Bern, 3010 Bern, Switzerland b Department of Pediatrics, University Children's Hospital, 3010 Bern, Switzerland c Department of Rheumatology, University Hospital, 3010 Bern, Switzerland article info abstract Article history: Fibroblast growth factor receptor-like 1 (FGFRL1) is a recently discovered transmembrane protein whose Received 20 July 2008 functions remain unclear. Since mutations in the related receptors FGFR1-3 cause skeletal malformations, Received in revised form 3 November 2008 DNA samples from 55 patients suffering from congenital skeletal malformations and 109 controls were Accepted 4 November 2008 searched for mutations in FGFRL1. One patient was identified harboring a frameshift mutation in the Available online 13 November 2008 intracellular domain of this novel receptor. The patient showed craniosynostosis, radio-ulnar synostosis and genital abnormalities and had previously been diagnosed with Antley–Bixler syndrome. The effect of the Keywords: Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) FGFRL1 mutation was studied in vitro. In a reporter gene assay, the wild-type as well as the mutant receptor Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibited FGF signaling. However, the mutant protein differed from the wild-type protein in its subcellular FGFRL1 localization. Mutant FGFRL1 was mainly found at the plasma membrane where it interacted with FGF ligands, Craniosynostosis while the wild-type protein was preferentially located in vesicular structures and the Golgi complex. -

Crouzono-Dermo-Skeletal Syndrome, Crouzon Syndrome with Acanthosis Nigricans Syndrome

Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 164–165 & 2014 Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved 0743-8346/14 www.nature.com/jp IMAGING CASE REPORT Crouzono-dermo-skeletal syndrome, Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans syndrome TE Herman, K Sargar and MJ Siegel Journal of Perinatology (2014) 34, 164–165; doi:10.1038/jp.2013.139 CASE PRESENTATION mutation-associated conditions include five skeletal dysplasias: A 3495 g infant girl was born at 39 weeks gestation to a 17-year- achondroplasia, hypochondroplasia, thanatophoric dysplasia type 1 old gravida 1, para 0 mother. The mother had Crouzon syndrome 1, thanatophoric dysplasia type 2 and SADDAM syndrome. and hydrocephalus. She had undergone 11 craniofacial and plastic surgical procedures. The mother previously had genetic testing, which demonstrated a mutation in exon 10 of the FGFR3 (fibroblast growth factor receptor number 3) gene consistent with Crouzon syndrome with acanthosis nigricans (AN), also called Crouzono-dermo-skeletal syndrome (CDSS). No sonographic abnormalities were detected in the fetus during the pregnancy. At delivery, the infant had Apgars of 1 at 1 min, 6 at 5 min and 7 at 10 min. A nasogastric tube could not be passed. The patient was noted to have proptosis, depressed nasal bridge, hypertelorism, an anterior ectopic anus and normal appearing skin. Craniofacial computed tomography (CT) scan was performed (Figures 1 and 2) and plain radiographs of the pelvis and lumbar spine obtained (Figure 3). DENOUEMENT AND DISCUSSION The craniofacial CT scan demonstrates bicoronal synostosis with marked midface hypoplasia, with exophthalmos and hypertelor- ism. In addition, there was bilateral marked choanal stenosis. The pelvis (Figure 3) demonstrates squared-off iliac wings with small sciatic notches and narrowing of the lumbar interpediculate distances.