Pathological Relationships Involving Iron and Myelin May Constitute a Shared Mechanism Linking Various Rare and Common Brain Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bioinformatics Approach for Pattern of Myelin-Specific Proteins And

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Qazvin University of Medical Sciences Repository Biotech Health Sci. 2016 November; 3(4):e38278. doi: 10.17795/bhs-38278. Published online 2016 August 16. Research Article Bioinformatics Approach for Pattern of Myelin-Specific Proteins and Related Human Disorders Samiie Pouragahi,1,2,3 Mohammad Hossein Sanati,4 Mehdi Sadeghi,2 and Marjan Nassiri-Asl3,* 1Department of Molecular Medicine, School of Medicine, Qazvin university of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, IR Iran 2Department of Bioinformatics, National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (NIGEB), Tehran, IR Iran 3Department of Pharmacology, Cellular and Molecular Research Center, School of Medicine, Qazvin university of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, IR Iran 4Department of Molecular Genetics, National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (NIGEB), Tehran, IR Iran *Corresponding author: Marjan Nassiri-Asl, School of Medicine, Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Qazvin, IR Iran. Tel: +98-2833336001, Fax: +98-2833324971, E-mail: [email protected] Received 2016 April 06; Revised 2016 May 30; Accepted 2016 June 22. Abstract Background: Recent neuroinformatic studies, on the structure-function interaction of proteins, causative agents basis of human disease have implied that dysfunction or defect of different protein classes could be associated with several related diseases. Objectives: The aim of this study was the use of bioinformatics approaches for understanding the structure, function and relation- ship of myelin protein 2 (PMP2), a myelin-basic protein in the basis of neuronal disorders. Methods: A collection of databases for exploiting classification information systematically, including, protein structure, protein family and classification of human disease, based on a new approach was used. -

Viewed Under 23 (B) Or 203 (C) fi M M Male Cko Mice, and Largely Unaffected Magni Cation; Scale Bars, 500 M (B) and 50 M (C)

BRIEF COMMUNICATION www.jasn.org Renal Fanconi Syndrome and Hypophosphatemic Rickets in the Absence of Xenotropic and Polytropic Retroviral Receptor in the Nephron Camille Ansermet,* Matthias B. Moor,* Gabriel Centeno,* Muriel Auberson,* † † ‡ Dorothy Zhang Hu, Roland Baron, Svetlana Nikolaeva,* Barbara Haenzi,* | Natalya Katanaeva,* Ivan Gautschi,* Vladimir Katanaev,*§ Samuel Rotman, Robert Koesters,¶ †† Laurent Schild,* Sylvain Pradervand,** Olivier Bonny,* and Dmitri Firsov* BRIEF COMMUNICATION *Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology and **Genomic Technologies Facility, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; †Department of Oral Medicine, Infection, and Immunity, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; ‡Institute of Evolutionary Physiology and Biochemistry, St. Petersburg, Russia; §School of Biomedicine, Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia; |Services of Pathology and ††Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University Hospital of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; and ¶Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France ABSTRACT Tight control of extracellular and intracellular inorganic phosphate (Pi) levels is crit- leaves.4 Most recently, Legati et al. have ical to most biochemical and physiologic processes. Urinary Pi is freely filtered at the shown an association between genetic kidney glomerulus and is reabsorbed in the renal tubule by the action of the apical polymorphisms in Xpr1 and primary fa- sodium-dependent phosphate transporters, NaPi-IIa/NaPi-IIc/Pit2. However, the milial brain calcification disorder.5 How- molecular identity of the protein(s) participating in the basolateral Pi efflux remains ever, the role of XPR1 in the maintenance unknown. Evidence has suggested that xenotropic and polytropic retroviral recep- of Pi homeostasis remains unknown. Here, tor 1 (XPR1) might be involved in this process. Here, we show that conditional in- we addressed this issue in mice deficient for activation of Xpr1 in the renal tubule in mice resulted in impaired renal Pi Xpr1 in the nephron. -

MLR) Model and Filtration

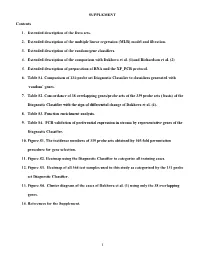

SUPPLEMENT Contents 1. Extended description of the Data sets. 2. Extended description of the multiple linear regression (MLR) model and filtration. 3. Extended description of the random-gene classifiers. 4. Extended description of the comparison with Dakhova et al. (1)and Richardson et al. (2) 5. Extended description of preparation of RNA and the XP_PCR protocol. 6. Table S1. Comparison of 131-probe set Diagnostic Classifier to classifiers generated with ‘random’ genes. 7. Table S2. Concordance of 38 overlapping genes/probe sets of the 339 probe sets ( basis) of the Diagnostic Classifier with the sign of differential change of Dakhova et al. (1). 8. Table S3. Function enrichment analysis. 9. Table S4. PCR validation of preferential expression in stroma by representative genes of the Diagnostic Classifier. 10. Figure S1. The incidence numbers of 339 probe sets obtained by 105-fold permutation procedure for gene selection. 11. Figure S2. Heatmap using the Diagnostic Classifier to categorize all training cases. 12. Figure S3. Heatmap of all 364 test samples used in this study as categorized by the 131 probe set Diagnostic Classifier. 13. Figure S4. Cluster diagram of the cases of Dakhova et al. (1) using only the 38 overlapping genes. 14. References for the Supplement. 1 1. Extended description of the Data Sets. Datasets 1 and 2 (Table 1) are based on post-prostatectomy frozen tissue samples obtained by informed consent using IRB-approved and HIPPA-compliant protocols. All tissues, except where noted, were collected at surgery and escorted to pathology for expedited review, dissection, and snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. -

Tfr2, Hfe, and Hjv in the Regulation of Body Iron Homeostasis

TFR2, HFE, AND HJV IN THE REGULATION OF BODY IRON HOMEOSTASIS By Christal Anna Worthen A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Cell & Developmental Biology and the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2014 School of Medicine Oregon Health & Science University CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ___________________________________ This is to certify that the PhD dissertation of Christal A Worthen has been approved ______________________________________ Caroline Enns, Ph.D., mentor ______________________________________ Peter Mayinger, Ph.D., Chairman ______________________________________ Philip Stork, M.D. ______________________________________ David Koeller, M.D. ______________________________________ Alex Nechiporuk, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS i List of Figures ii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations v Abstract: 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 5 Abstract and Introduction 6 Binding partners, regulation, and trafficking of TFR2 9 Disease-causing mutations in TFR2 12 Hepcidin regulation 12 Physiological function of TFR2 15 Current TFR2 models 18 Summary 19 Figure 21 Chapter 2: The cytoplasmic domain of TFR2 is necessary for 22 HFE, HJV, and TFR2 regulation of hepcidin Abstract 23 Capsule & Introduction 24 Materials and Methods 26 Results 32 Figures 41 Discussion 49 Chapter 3: Lack of functional TFR2 results in stress erythropoiesis 53 Introduction 54 Materials and Methods 55 Results 57 Figures 60 Discussion 65 Chapter 4: Conclusions and future directions 67 Appendices Appendix A: Coculture of HepG2 cells reduces hepcidin expression 71 Appendix B: Hfe-/- macrophages handle iron differently 80 Appendix C: Both ZIP14A and ZIP14B are regulated by HFE and iron 91 Appendix D: The cytoplasmic domain of HFE does not interact with 99 ZIP14 loop 2 by yeast-2-hybris References 105 i LIST OF FIGURES Figure Abstract 1: Body iron homeostasis. -

Supplementary Table 1. Down-Regulation of Oligodendrocyte Genes in Schizophrenia

Supplementary Table 1. Down-regulation of oligodendrocyte genes in schizophrenia Schizophrenia ID Accession Symbol product fold change P value oligodendrocyte transcription factors 36018_at AJ001183 SOX10 SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 10 -1.60 0.001 40624_at U48250 OLIG2 oligodendrocyte lineage transcription factor 2 -1.30 0.019 32187_at AB028973 MYT1 myelin transcription factor 1 1.12 0.571 33539_at W28567 MYEF2 myelin expression factor 2 -1.04 0.887 oligodendrocyte-expressed genes 38558_at M29273 MAG myelin associated glycoprotein -1.76 0.004 41158_at M54927 PLP1 proteolipid protein 1 -1.50 0.011 38499_s_at D28113 MOBP myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein -1.59 0.017 35903_at M63623 OMG oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein -1.15 0.022 38653_at D11428 PMP22 peripheral myelin protein 22 -1.28 0.058 38051_at X76220 MAL mal, T-cell differentiation protein -1.11 0.065 612_s_at M19650 CNP 2',3'-cyclic nucleotide 3' phosphodiesterase -1.17 0.072 32538_at S95936 TF transferrin -1.48 0.098 32612_at X04412 GSN gelsolin (amyloidosis, Finnish type) -1.23 0.118 39598_at X04325 GJB1 gap junction protein, beta 1, 32kDa -1.10 0.416 37867_at Z48051 MOG myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 1.39 0.600 35328_at AF055023 NF1 neurofibromin 1 -1.03 0.973 35817_at M13577 MBP myelin basic protein 1.02 1 other oligodendrocyte-related genes 41346_at AJ007583 LARGE like-glycosyltransferase -1.02 0.786 32719_at L41827 NRG1 neuregulin 1 1.07 0.792 1585_at M34309 ERBB3 v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3 -1.10 0.294 40387_at U80811 -

Basic Protein Detect Circulating Antibodies in Ataxic Horses Siobhan P Ellison Tom J Kennedy Austin Li

Neuritogenic Peptides Derived from Equine Myelin P2 Basic Protein Detect Circulating Antibodies in Ataxic Horses Siobhan P Ellison Tom J Kennedy Austin Li Corresponding Author: Siobhan P. Ellison, DVM PhD 15471 NW 112th Ave Reddick, Fl 32686 Phone: 352-591-3221 Fax: 352-591-4318 e-mail: [email protected] KEY WORDS: Need Keywords nosis of EPM. No cross-reactivity between the antigens was observed. An evaluation of the agreement between the assays (McNe- ABSTRACT mar’s test) suggests as CRP values increase, the likelihood of a positive MPP ELISA also Polyneuritis equi is an immune-mediated increases. Clinical signs of EPM may be neurodegenerative condition in horses that is due to an immune-mediated polyneuropathy related to circulating demyelinating anti- that involves complex in vivo interactions bodies against equine myelin basic protein with the IL6 pathway because MPP antibod- 2 (MP ). The present study examined the 2 ies and elevated CRP concentrations were presence of circulating demyelinating anti- detected in some horses with S. neurona bodies against neuritogenic peptides of MP 2 sarcocystosis. in sera from horses suspected of equine pro- tozoal encephalomyelitis (EPM), a neurode- INTRODUCTION generative condition in horses that may be Polyneuritis equi is a neurodegenerative immune-mediated. The goals of this study condition in horses that is related to circulat- were to develop serum ELISA tests that may ing demyelinating antibodies against equine identify neuroinflammatory conditions in myelin basic protein 2 (MP2). The clinical horses with EPM and indirectly relate the signs of polyneuritis equi (PE) are simi- pathogenesis of inflammation to IL6 by se- lar to equine protozoal myeloencephalitis rum C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration. -

The Intrinsically Disordered Proteins of Myelin in Health and Disease

cells Review Flexible Players within the Sheaths: The Intrinsically Disordered Proteins of Myelin in Health and Disease Arne Raasakka 1 and Petri Kursula 1,2,* 1 Department of Biomedicine, University of Bergen, Jonas Lies vei 91, NO-5009 Bergen, Norway; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine & Biocenter Oulu, University of Oulu, Aapistie 7A, FI-90220 Oulu, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 January 2020; Accepted: 16 February 2020; Published: 18 February 2020 Abstract: Myelin ensheathes selected axonal segments within the nervous system, resulting primarily in nerve impulse acceleration, as well as mechanical and trophic support for neurons. In the central and peripheral nervous systems, various proteins that contribute to the formation and stability of myelin are present, which also harbor pathophysiological roles in myelin disease. Many myelin proteins have common attributes, including small size, hydrophobic segments, multifunctionality, longevity, and regions of intrinsic disorder. With recent advances in protein biophysical characterization and bioinformatics, it has become evident that intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) are abundant in myelin, and their flexible nature enables multifunctionality. Here, we review known myelin IDPs, their conservation, molecular characteristics and functions, and their disease relevance, along with open questions and speculations. We place emphasis on classifying the molecular details of IDPs in myelin, and we correlate these with their various functions, including susceptibility to post-translational modifications, function in protein–protein and protein–membrane interactions, as well as their role as extended entropic chains. We discuss how myelin pathology can relate to IDPs and which molecular factors are potentially involved. Keywords: myelin; intrinsically disordered protein; multiple sclerosis; peripheral neuropathies; myelination; protein folding; protein–membrane interaction; protein–protein interaction 1. -

2013 New Molecular CPT Co

Cleveland Clinic Laboratories 2013 New Molecular CPT Codes 2013 Test Name Order Code Billing Code CPT Codes 2012 CPT Codes ACADM PCR, Complete, Tier 2 ACADM 88175 81404 83891, 83894x10, 83898x10, 83904x20 ACTA2 Gene Sequencing ACTA2 88528 81403 83898x9, 83904x9, 83891 ADmark ApoE Genotype (Symptomatic) APOALZ 82397 81401 83892, 83894, 83898, 81401, 83891 ADmark PS-1 Analysis, Symptomatic PS1SY 83019 81405 83904x10, 83909x10, 83898x10, 83891 Alpha Globin (HBA1 and HBA2) Sequencing HBA12 88847 81257 New test in 2013 Alpha Thalassemia Gene Deletion ATHAL 84123 81257 83891, 83900, 83901x8, 83894 Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Quantitation and Phenotyping PHA1A 84187 81332 82103, 82104 Angelman UBE3A Sequencing UBE3A 88200 81331 83898x8, 83904x10, 83909x10 APO E Genotype APOEG 79374 81401 83891, 81401, 83898, 83896x2 ARX Sequence Analysis ARXSEQ 87860 81404 83890, 83898x5, 83894, 83904x6 Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Evaluation AIRE 83293 81479 83909x14, 83891, 83898x14, 83904x14 Autosomal Dom Ataxia Evaluation AUTOAT 82179 81401, 83909x88, 83898x88, 83904x77, 81479x13 83891 Barth Syndrome, Carrier BARCAR 82536 81406 83891, 83898, 83904x2 Barth Syndrome, Initial Patient BARINI 82535 81406 83891, 83898, 83904x9 Bartonella PCR, Tissue TBART 87924 87471 83898x4, 83890, 83894 B-Cell Clonality Using BIOMED-2 PCR Primers BCBMD 87904 81261, 83891, 83900, 83909x5, 83898x3, 83901x2, 81264 83912, 81261, 81264 BCL 2 mbr (PCR) BCL2 81099 81401 81401, 83890, 83898, 83894, 83912 BCR/ABL Kinase Domain Mutation Analysis KINASE 84529 81403 83891, 83898, 83902, 83904x4, -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Figure S1. The functionality of the tagged Arp6 and Swr1 was confirmed by monitoring cell growth and sensitivity to hydeoxyurea (HU). Five-fold serial dilutions of each strain were plated on YPD with or without 50 mM HU and incubated at 30°C or 37°C for 3 days. Figure S2. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 3. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position of Tel 3L, Tel 3R, CEN3, and the RP gene are shown under the panels. Figure S3. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 4. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) in the whole chromosome region are compared. The position of Tel 4L, Tel 4R, CEN4, SWR1, and RP genes are shown under the panels. Figure S4. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on the region including the SWR1 gene of chromosome 4. The binding of Arp6- FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position and orientation of the SWR1 gene is shown. Figure S5. Localization of Arp6 and Swr1 on chromosome 5. The binding of Arp6-FLAG (top), Swr1-FLAG (middle), and Arp6-FLAG in swr1 cells (bottom) are compared. The position of Tel 5L, Tel 5R, CEN5, and the RP genes are shown under the panels. Figure S6. Preferential localization of Arp6 and Swr1 in the 5′ end of genes. Vertical bars represent the binding ratio of proteins in each locus. -

Yeast Genome Gazetteer P35-65

gazetteer Metabolism 35 tRNA modification mitochondrial transport amino-acid metabolism other tRNA-transcription activities vesicular transport (Golgi network, etc.) nitrogen and sulphur metabolism mRNA synthesis peroxisomal transport nucleotide metabolism mRNA processing (splicing) vacuolar transport phosphate metabolism mRNA processing (5’-end, 3’-end processing extracellular transport carbohydrate metabolism and mRNA degradation) cellular import lipid, fatty-acid and sterol metabolism other mRNA-transcription activities other intracellular-transport activities biosynthesis of vitamins, cofactors and RNA transport prosthetic groups other transcription activities Cellular organization and biogenesis 54 ionic homeostasis organization and biogenesis of cell wall and Protein synthesis 48 plasma membrane Energy 40 ribosomal proteins organization and biogenesis of glycolysis translation (initiation,elongation and cytoskeleton gluconeogenesis termination) organization and biogenesis of endoplasmic pentose-phosphate pathway translational control reticulum and Golgi tricarboxylic-acid pathway tRNA synthetases organization and biogenesis of chromosome respiration other protein-synthesis activities structure fermentation mitochondrial organization and biogenesis metabolism of energy reserves (glycogen Protein destination 49 peroxisomal organization and biogenesis and trehalose) protein folding and stabilization endosomal organization and biogenesis other energy-generation activities protein targeting, sorting and translocation vacuolar and lysosomal -

How Does Protein Zero Assemble Compact Myelin?

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 13 May 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202005.0222.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Cells 2020, 9, 1832; doi:10.3390/cells9081832 Perspective How Does Protein Zero Assemble Compact Myelin? Arne Raasakka 1,* and Petri Kursula 1,2 1 Department of Biomedicine, University of Bergen, Jonas Lies vei 91, NO-5009 Bergen, Norway 2 Faculty of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine & Biocenter Oulu, University of Oulu, Aapistie 7A, FI-90220 Oulu, Finland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Myelin protein zero (P0), a type I transmembrane protein, is the most abundant protein in peripheral nervous system (PNS) myelin – the lipid-rich, periodic structure that concentrically encloses long axonal segments. Schwann cells, the myelinating glia of the PNS, express P0 throughout their development until the formation of mature myelin. In the intramyelinic compartment, the immunoglobulin-like domain of P0 bridges apposing membranes together via homophilic adhesion, forming a dense, macroscopic ultrastructure known as the intraperiod line. The C-terminal tail of P0 adheres apposing membranes together in the narrow cytoplasmic compartment of compact myelin, much like myelin basic protein (MBP). In mouse models, the absence of P0, unlike that of MBP or P2, severely disturbs the formation of myelin. Therefore, P0 is the executive molecule of PNS myelin maturation. How and when is P0 trafficked and modified to enable myelin compaction, and how disease mutations that give rise to incurable peripheral neuropathies alter the function of P0, are currently open questions. The potential mechanisms of P0 function in myelination are discussed, providing a foundation for the understanding of mature myelin development and how it derails in peripheral neuropathies. -

Supplemental Data

MOLECULAR PHARMACOLOGY Supplemental Data Regulation of M3 Muscarinic Receptor Expression and Function by Transmembrane Protein 147 Erica Rosemond, Mario Rossi, Sara M. McMillin, Marco Scarselli, Julie G. Donaldson, and Jürgen Wess Supplemental Table 1 M3R-interacting proteins identified in a membrane-based yeast two-hybrid screen Accession Protein No. Tetraspanin family CD82 AAB23825 CD9 P21926 CD63 AAV38940 Ubiquitin-associated proteins Small ubiquitin-related modifier 2 precursor (SUMO-1) AAC50996 Small ubiquitin-related modifier 2 precursor (SUMO-2) P61956 UBC protein AAH08955 Ubiquitin C NP_066289 Receptor proteins/Transmembrane proteins AAH01118 / Transmembrane protein 147 BC001118 G protein-coupled receptor 37 NP_005293 NM_016235 / Homo sapiens G protein-coupled receptor, family C, group 5, member B (GPRC5B) AAF05331 Rhodopsin NP_000530 Aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) P55087 Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate-associated protein 1 NP_001009184 Sodium channel, voltage gated, type VIII, alpha NP_055006 Transmembrane 9 superfamily member 2 CAH71381 Transmembrane protein 14A AAH19328 Signaling molecules Phosphatidic acid phosphatase type 2C AAP35667 Calmodulin 2 AAH08437 Protein kinase Njmu-R1 AAH54035 2',3'-Cyclic nucleotide 3' phosphodiesterase (CNP) AAH06392 Solute carrier proteins Solute carrier family 39 (zinc transporter), member 3 isoform a NP_653165 Solute carrier family 22 (organic cation transporter), member 17 isoform b NP_057693 Solute carrier family 31 (copper transporters), member 2 NP_001851 Solute carrier family