The Timing and Extent of Motor Neuron Vulnerability in ALS Correlates with Accumulation of Misfolded SOD1 Protein in the Cortex and in the Spinal Cord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia

brain sciences Review Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper Motor Neuron Dominant Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Timothy Fullam and Jeffrey Statland * Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas, KS 66160, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Following the exclusion of potentially reversible causes, the differential for those patients presenting with a predominant upper motor neuron syndrome includes primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), or upper motor neuron dominant ALS (UMNdALS). Differentiation of these disorders in the early phases of disease remains challenging. While no single clinical or diagnostic tests is specific, there are several developing biomarkers and neuroimaging technologies which may help distinguish PLS from HSP and UMNdALS. Recent consensus diagnostic criteria and use of evolving technologies will allow more precise delineation of PLS from other upper motor neuron disorders and aid in the targeting of potentially disease-modifying therapeutics. Keywords: primary lateral sclerosis; amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; hereditary spastic paraplegia Citation: Fullam, T.; Statland, J. Upper Motor Neuron Disorders: Primary Lateral Sclerosis, Upper 1. Introduction Motor Neuron Dominant Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893) and Wilhelm Erb (1840–1921) are credited with first Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, and describing a distinct clinical syndrome of upper motor neuron (UMN) tract degeneration in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia. Brain isolation with symptoms including spasticity, hyperreflexia, and mild weakness [1,2]. Many Sci. 2021, 11, 611. https:// of the earliest described cases included cases of hereditary spastic paraplegia, amyotrophic doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050611 lateral sclerosis, and underrecognized structural, infectious, or inflammatory etiologies for upper motor neuron dysfunction which have since become routinely diagnosed with the Academic Editors: P. -

Neural Control of Movement: Motor Neuron Subtypes, Proprioception and Recurrent Inhibition

List of Papers This thesis is based on the following papers, which are referred to in the text by their Roman numerals. I Enjin A, Rabe N, Nakanishi ST, Vallstedt A, Gezelius H, Mem- ic F, Lind M, Hjalt T, Tourtellotte WG, Bruder C, Eichele G, Whelan PJ, Kullander K (2010) Identification of novel spinal cholinergic genetic subtypes disclose Chodl and Pitx2 as mark- ers for fast motor neurons and partition cells. J Comp Neurol 518:2284-2304. II Wootz H, Enjin A, Wallen-Mackenzie Å, Lindholm D, Kul- lander K (2010) Reduced VGLUT2 expression increases motor neuron viability in Sod1G93A mice. Neurobiol Dis 37:58-66 III Enjin A, Leao KE, Mikulovic S, Le Merre P, Tourtellotte WG, Kullander K. 5-ht1d marks gamma motor neurons and regulates development of sensorimotor connections Manuscript IV Enjin A, Leao KE, Eriksson A, Larhammar M, Gezelius H, Lamotte d’Incamps B, Nagaraja C, Kullander K. Development of spinal motor circuits in the absence of VIAAT-mediated Renshaw cell signaling Manuscript Reprints were made with permission from the respective publishers. Cover illustration Carousel by Sasha Svensson Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................9 Background...................................................................................................11 Neural control of movement.....................................................................11 The motor neuron.....................................................................................12 Organization -

ALS and Other Motor Neuron Diseases Can Represent Diagnostic Challenges

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Ezgi Tiryaki, Hennepin ALS and Other Motor County Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 701 Park Avenue P5-200, Neuron Diseases Minneapolis, MN 55415, [email protected]. Ezgi Tiryaki, MD; Holli A. Horak, MD, FAAN Relationship Disclosure: Dr Tiryaki’s institution receives support from The ALS Association. Dr Horak’s ABSTRACT institution receives a grant from the Centers for Disease Purpose of Review: This review describes the most common motor neuron disease, Control and Prevention. ALS. It discusses the diagnosis and evaluation of ALS and the current understanding of its Unlabeled Use of pathophysiology, including new genetic underpinnings of the disease. This article also Products/Investigational covers other motor neuron diseases, reviews how to distinguish them from ALS, and Use Disclosure: Drs Tiryaki and Horak discuss discusses their pathophysiology. the unlabeled use of various Recent Findings: In this article, the spectrum of cognitive involvement in ALS, new concepts drugs for the symptomatic about protein synthesis pathology in the etiology of ALS, and new genetic associations will be management of ALS. * 2014, American Academy covered. This concept has changed over the past 3 to 4 years with the discovery of new of Neurology. genes and genetic processes that may trigger the disease. As of 2014, two-thirds of familial ALS and 10% of sporadic ALS can be explained by genetics. TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43), for instance, has been shown to cause frontotemporal dementia as well as some cases of familial ALS, and is associated with frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS. Summary: The anterior horn cells control all voluntary movement: motor activity, res- piratory, speech, and swallowing functions are dependent upon signals from the anterior horn cells. -

A System for Studying Mechanisms of Neuromuscular Junction Development and Maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 2464-2477 doi:10.1242/dev.130278 TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES RESEARCH ARTICLE A system for studying mechanisms of neuromuscular junction development and maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R. Gomes1,3,*,‡ ABSTRACT different animal models and cell lines (Chen et al., 2014; Corti et al., The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cellular synapse between a 2012; Lenzi et al., 2015) with the hope of recapitulating some motor neuron and a skeletal muscle fiber, enables the translation of features of neuromuscular diseases and understanding the triggers chemical cues into physical activity. The development of this special of one of their common hallmarks: the disruption of the structure has been subject to numerous investigations, but its neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the most complexity renders in vivo studies particularly difficult to perform. studied synapses. It is formed of three key elements: the lower motor In vitro modeling of the neuromuscular junction represents a powerful neuron (the pre-synaptic compartment), the skeletal muscle (the tool to delineate fully the fine tuning of events that lead to subcellular post-synaptic compartment) and the Schwann cell (Sanes and specialization at the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites. Here, we Lichtman, 1999). The NMJ is formed in a step-wise manner describe a novel heterologous co-culture in vitro method using rat following a series of cues involving these three cellular components spinal cord explants with dorsal root ganglia and murine primary and its role is basically to ensure the skeletal muscle functionality. -

Reaction to Injury & Regeneration

Reaction to Injury & Regeneration Steven McLoon Department of Neuroscience University of Minnesota 1 The adult mammalian central nervous system has the lowest regenerative capacity of all organ systems. 2 3 Reaction to Axotomy Function distal to the axon cut is lost. (immediate) 4 Reaction to Axotomy • Spinal cord injury results in an immediate loss of sensation and muscle paralysis below the level of the injury. Spinal cord injury can be partial or complete, and the sensory/motor loss depends on which axons are injured. • Peripheral nerve injury results in an immediate loss of sensation and muscle paralysis in the areas served by the injured nerve distal to the site of injury. 5 Reaction to Axotomy K+ leaks out of the cell and Na+/Ca++ leak into the cell. (seconds) Proximal and distal segments of the axon reseal slightly away from the cut ends. (~2 hrs) Subsequent anterograde & retrograde effects … 6 Anterograde Effects (Wallerian Degeneration) Axon swells. (within 12 hrs) Axolema and mitochondria begin to fragment. (within 3 days) Myelin not associated with a viable axon begins to fragment. (within 1 wk) Astrocytes or Schwann cells proliferate (within 1 wk), which can continue for over a month. Results in >10x the original number of cells. Microglia (or macrophages in the PNS) invade the area. Glia and microglia phagocytize debris. (1 month in PNS; >3 months in CNS) 7 Anterograde Effects (Wallerian Degeneration) Degradation of the axon involves self proteolysis: In the ‘Wallerian degeneration slow’ (Wlds) mouse mutation, the distal portion of severed axons are slow to degenerate; the dominant mutation involves a ubiquitin regulatory enzyme. -

Cranial Nerves 1, 5, 7-12

Cranial Nerve I Olfactory Nerve Nerve fiber modality: Special sensory afferent Cranial Nerves 1, 5, 7-12 Function: Olfaction Remarkable features: – Peripheral processes act as sensory receptors (the other special sensory nerves have separate Warren L Felton III, MD receptors) Professor and Associate Chair of Clinical – Primary afferent neurons undergo continuous Activities, Department of Neurology replacement throughout life Associate Professor of Ophthalmology – Primary afferent neurons synapse with secondary neurons in the olfactory bulb without synapsing Chair, Division of Neuro-Ophthalmology first in the thalamus (as do all other sensory VCU School of Medicine neurons) – Pathways to cortical areas are entirely ipsilateral 1 2 Crania Nerve I Cranial Nerve I Clinical Testing Pathology Anosmia, hyposmia: loss of or impaired Frequently overlooked in neurologic olfaction examination – 1% of population, 50% of population >60 years Aromatic stimulus placed under each – Note: patients with bilateral anosmia often report nostril with the other nostril occluded, eg impaired taste (ageusia, hypogeusia), though coffee, cloves, or soap taste is normal when tested Note that noxious stimuli such as Dysosmia: disordered olfaction ammonia are not used due to concomitant – Parosmia: distorted olfaction stimulation of CN V – Olfactory hallucination: presence of perceived odor in the absence of odor Quantitative clinical tests are available: • Aura preceding complex partial seizures of eg, University of Pennsylvania Smell temporal lobe origin -

Lancl1 Promotes Motor Neuron Survival and Extends the Lifespan of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Mice

Cell Death & Differentiation (2020) 27:1369–1382 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-019-0422-6 ARTICLE LanCL1 promotes motor neuron survival and extends the lifespan of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mice 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Honglin Tan ● Mina Chen ● Dejiang Pang ● Xiaoqiang Xia ● Chongyangzi Du ● Wanchun Yang ● Yiyuan Cui ● 1,2 1 1,3 4 4 3 1,5 Chao Huang ● Wanxiang Jiang ● Dandan Bi ● Chunyu Li ● Huifang Shang ● Paul F. Worley ● Bo Xiao Received: 19 November 2018 / Revised: 3 September 2019 / Accepted: 6 September 2019 / Published online: 30 September 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. This article is published with open access Abstract Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive loss of motor neurons. Improving neuronal survival in ALS remains a significant challenge. Previously, we identified Lanthionine synthetase C-like protein 1 (LanCL1) as a neuronal antioxidant defense gene, the genetic deletion of which causes apoptotic neurodegeneration in the brain. Here, we report in vivo data using the transgenic SOD1G93A mouse model of ALS indicating that CNS-specific expression of LanCL1 transgene extends lifespan, delays disease onset, decelerates symptomatic progression, and improves motor performance of SOD1G93A mice. Conversely, CNS-specific deletion of fl 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: LanCL1 leads to neurodegenerative phenotypes, including motor neuron loss, neuroin ammation, and oxidative damage. Analysis reveals that LanCL1 is a positive regulator of AKT activity, and LanCL1 overexpression restores the impaired AKT activity in ALS model mice. These findings indicate that LanCL1 regulates neuronal survival through an alternative mechanism, and suggest a new therapeutic target in ALS. -

GDE2 Regulates Subtype-Specific Motor Neuron Generation Through

Neuron Article GDE2 Regulates Subtype-Specific Motor Neuron Generation through Inhibition of Notch Signaling Priyanka Sabharwal,1 Changhee Lee,1 Sungjin Park,1 Meenakshi Rao,1,2 and Shanthini Sockanathan1,* 1The Solomon Snyder Department of Neuroscience, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, PCTB1004, 725 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA 2Present address: Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Boston, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] DOI 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.028 SUMMARY which is innervated by specific groups of motor neurons. Indi- vidual motor neuron groups are highly organized in terms of their The specification of spinal interneuron and motor cell body distribution, projection patterns, and function and neuron identities initiates within progenitor cells, consist of force-generating alpha motor neurons that innervate while motor neuron subtype diversification is regu- extrafusal muscle fibers and stretch-sensitive gamma motor lated by hierarchical transcriptional programs imple- neurons that innervate intrafusal muscle fibers of the muscle mented postmitotically. Here we find that mice lack- spindles (Dasen and Jessell, 2009; reviewed in Kanning et al., ing GDE2, a six-transmembrane protein that triggers 2010). The integration of input from both alpha and gamma motor neurons is essential for coordinated motor movement to motor neuron generation, exhibit selective losses occur (Kanning et al., 2010). of distinct motor neuron subtypes, specifically in How is diversity engendered in developing motor neurons? defined subsets of limb-innervating motor pools All motor neurons initially derive from ventral progenitor cells that correlate with the loss of force-generating alpha that are specified to become Olig2+ motor neuron progenitors motor neurons. -

Reduction of Ephrin-A5 Aggravates Disease Progression in Amyotrophic

Rué et al. Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2019) 7:114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019-0759-6 RESEARCH Open Access Reduction of ephrin-A5 aggravates disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Laura Rué1,2 , Patrick Oeckl3, Mieke Timmers1,2, Annette Lenaerts1,2, Jasmijn van der Vos1,2, Silke Smolders1,2, Lindsay Poppe1,2, Antina de Boer1,2, Ludo Van Den Bosch1,2, Philip Van Damme1,2,4, Jochen H. Weishaupt3, Albert C. Ludolph3, Markus Otto3, Wim Robberecht1,4 and Robin Lemmens1,2,4* Abstract Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects motor neurons in the brainstem, spinal cord and motor cortex. ALS is characterized by genetic and clinical heterogeneity, suggesting the existence of genetic factors that modify the phenotypic expression of the disease. We previously identified the axonal guidance EphA4 receptor, member of the Eph-ephrin system, as an ALS disease-modifying factor. EphA4 genetic inhibition rescued the motor neuron phenotype in zebrafish and a rodent model of ALS. Preventing ligands from binding to the EphA4 receptor also successfully improved disease, suggesting a role for EphA4 ligands in ALS. One particular ligand, ephrin-A5, is upregulated in reactive astrocytes after acute neuronal injury and inhibits axonal regeneration. Moreover, it plays a role during development in the correct pathfinding of motor axons towards their target limb muscles. We hypothesized that a constitutive reduction of ephrin-A5 signalling would benefit disease progression in a rodent model for ALS. We discovered that in the spinal cord of control and symptomatic ALS mice ephrin-A5 was predominantly expressed in neurons. -

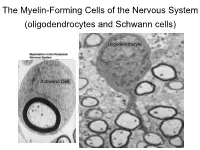

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

Cortex Brainstem Spinal Cord Thalamus Cerebellum Basal Ganglia

Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology HST.131: Introduction to Neuroscience Course Director: Dr. David Corey Motor Systems I 1 Emad Eskandar, MD Motor Systems I - Muscles & Spinal Cord Introduction Normal motor function requires the coordination of multiple inter-elated areas of the CNS. Understanding the contributions of these areas to generating movements and the disturbances that arise from their pathology are important challenges for the clinician and the scientist. Despite the importance of diseases that cause disorders of movement, the precise function of many of these areas is not completely clear. The main constituents of the motor system are the cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Cortex Basal Ganglia Cerebellum Thalamus Brainstem Spinal Cord In very broad terms, cortical motor areas initiate voluntary movements. The cortex projects to the spinal cord directly, through the corticospinal tract - also known as the pyramidal tract, or indirectly through relay areas in the brain stem. The cortical output is modified by two parallel but separate re entrant side loops. One loop involves the basal ganglia while the other loop involves the cerebellum. The final outputs for the entire system are the alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord, also called the Lower Motor Neurons. Cortex: Planning and initiation of voluntary movements and integration of inputs from other brain areas. Basal Ganglia: Enforcement of desired movements and suppression of undesired movements. Cerebellum: Timing and precision of fine movements, adjusting ongoing movements, motor learning of skilled tasks Brain Stem: Control of balance and posture, coordination of head, neck and eye movements, motor outflow of cranial nerves Spinal Cord: Spontaneous reflexes, rhythmic movements, motor outflow to body. -

Motor Neuron Disease Motor Neuron Disease

Motor Neuron Disease Motor Neuron Disease • Incidence: 2-4 per 100 000 • Onset: usually 50-70 years • Pathology: – Degenerative condition – anterior horn cells and upper motor neurons in spinal cord, resulting in mixed upper and lower motor neuron signs • Cause unknown – 10% familial (SOD-1 mutation) – ? Related to athleticism Presentation • Several variations in onset, but progress to the same endpoint • Motor nerves only affected • May be just UMN or just LMN at onset, but other features will appear over time • Main patterns: – Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis – Bulbar presentaion – Primary lateral sclerosis (UMN onset) – Progressive muscular atrophy (LMN onset) Questions Wasting Classification • Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis • Progressive Bulbar Palsy • Progressive Muscular Atrophy • Primary Lateral Sclerosis • Multifocal Motor Neuropathy • Spinal Muscular Atrophy • Kennedy’s Disease • Monomelic Amyotrophy • Brachial Amyotrophic Diplegia El Escorial Criteria for Diagnosis Tongue fasiculations Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis • ‘Typical’ presentation (60%+) • Usually one limb initially – Foot drop – Clumsy weak hand – May complain of cramps • Gradual progression over months • May be some wasting at presentation • Usually fasiculations (often more widespread) • Brisk reflexes, extensor plantars • No sensory signs; MAY occasionally be mild symptoms • Relentless progression, noticable over weeks/ months Bulbar MND • Approximately 30% of cases • Onset with dysarthria, dysphagia • Bulbar and pseudobulbar symptoms • On examination – Dysarthria –