Chapter 6 Phase Transitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes: BCS Theory of Superconductivity

Lecture Notes: BCS theory of superconductivity Prof. Rafael M. Fernandes Here we will discuss a new ground state of the interacting electron gas: the superconducting state. In this macroscopic quantum state, the electrons form coherent bound states called Cooper pairs, which dramatically change the macroscopic properties of the system, giving rise to perfect conductivity and perfect diamagnetism. We will mostly focus on conventional superconductors, where the Cooper pairs originate from a small attractive electron-electron interaction mediated by phonons. However, in the so- called unconventional superconductors - a topic of intense research in current solid state physics - the pairing can originate even from purely repulsive interactions. 1 Phenomenology Superconductivity was discovered by Kamerlingh-Onnes in 1911, when he was studying the transport properties of Hg (mercury) at low temperatures. He found that below the liquifying temperature of helium, at around 4:2 K, the resistivity of Hg would suddenly drop to zero. Although at the time there was not a well established model for the low-temperature behavior of transport in metals, the result was quite surprising, as the expectations were that the resistivity would either go to zero or diverge at T = 0, but not vanish at a finite temperature. In a metal the resistivity at low temperatures has a constant contribution from impurity scattering, a T 2 contribution from electron-electron scattering, and a T 5 contribution from phonon scattering. Thus, the vanishing of the resistivity at low temperatures is a clear indication of a new ground state. Another key property of the superconductor was discovered in 1933 by Meissner. -

Phase-Transition Phenomena in Colloidal Systems with Attractive and Repulsive Particle Interactions Agienus Vrij," Marcel H

Faraday Discuss. Chem. SOC.,1990,90, 31-40 Phase-transition Phenomena in Colloidal Systems with Attractive and Repulsive Particle Interactions Agienus Vrij," Marcel H. G. M. Penders, Piet W. ROUW,Cornelis G. de Kruif, Jan K. G. Dhont, Carla Smits and Henk N. W. Lekkerkerker Van't Hof laboratory, University of Utrecht, Padualaan 8, 3584 CH Utrecht, The Netherlands We discuss certain aspects of phase transitions in colloidal systems with attractive or repulsive particle interactions. The colloidal systems studied are dispersions of spherical particles consisting of an amorphous silica core, coated with a variety of stabilizing layers, in organic solvents. The interaction may be varied from (steeply) repulsive to (deeply) attractive, by an appropri- ate choice of the stabilizing coating, the temperature and the solvent. In systems with an attractive interaction potential, a separation into two liquid- like phases which differ in concentration is observed. The location of the spinodal associated with this demining process is measured with pulse- induced critical light scattering. If the interaction potential is repulsive, crystallization is observed. The rate of formation of crystallites as a function of the concentration of the colloidal particles is studied by means of time- resolved light scattering. Colloidal systems exhibit phase transitions which are also known for molecular/ atomic systems. In systems consisting of spherical Brownian particles, liquid-liquid phase separation and crystallization may occur. Also gel and glass transitions are found. Moreover, in systems containing rod-like Brownian particles, nematic, smectic and crystalline phases are observed. A major advantage for the experimental study of phase equilibria and phase-separation kinetics in colloidal systems over molecular systems is the length- and time-scales that are involved. -

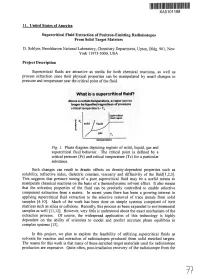

Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes from Solid Target Matrices

XA0101188 11. United States of America Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes From Solid Target Matrices D. Schlyer, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Chemistry Department, Upton, Bldg. 901, New York 11973-5000, USA Project Description Supercritical fluids are attractive as media for both chemical reactions, as well as process extraction since their physical properties can be manipulated by small changes in pressure and temperature near the critical point of the fluid. What is a supercritical fluid? Above a certain temperature, a vapor can no longer be liquefied regardless of pressure critical temperature - Tc supercritical fluid r«gi on solid a u & temperature Fig. 1. Phase diagram depicting regions of solid, liquid, gas and supercritical fluid behavior. The critical point is defined by a critical pressure (Pc) and critical temperature (Tc) for a particular substance. Such changes can result in drastic effects on density-dependent properties such as solubility, refractive index, dielectric constant, viscosity and diffusivity of the fluid[l,2,3]. This suggests that pressure tuning of a pure supercritical fluid may be a useful means to manipulate chemical reactions on the basis of a thermodynamic solvent effect. It also means that the solvation properties of the fluid can be precisely controlled to enable selective component extraction from a matrix. In recent years there has been a growing interest in applying supercritical fluid extraction to the selective removal of trace metals from solid samples [4-10]. Much of the work has been done on simple systems comprised of inert matrices such as silica or cellulose. Recently, this process as been expanded to environmental samples as well [11,12]. -

Phase Transitions in Quantum Condensed Matter

Diss. ETH No. 15104 Phase Transitions in Quantum Condensed Matter A dissertation submitted to the SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY ZURICH¨ (ETH Zuric¨ h) for the degree of Doctor of Natural Science presented by HANS PETER BUCHLER¨ Dipl. Phys. ETH born December 5, 1973 Swiss citizien accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. J. W. Blatter, examiner Prof. Dr. W. Zwerger, co-examiner PD. Dr. V. B. Geshkenbein, co-examiner 2003 Abstract In this thesis, phase transitions in superconducting metals and ultra-cold atomic gases (Bose-Einstein condensates) are studied. Both systems are examples of quantum condensed matter, where quantum effects operate on a macroscopic level. Their main characteristics are the condensation of a macroscopic number of particles into the same quantum state and their ability to sustain a particle current at a constant velocity without any driving force. Pushing these materials to extreme conditions, such as reducing their dimensionality or enhancing the interactions between the particles, thermal and quantum fluctuations start to play a crucial role and entail a rich phase diagram. It is the subject of this thesis to study some of the most intriguing phase transitions in these systems. Reducing the dimensionality of a superconductor one finds that fluctuations and disorder strongly influence the superconducting transition temperature and eventually drive a superconductor to insulator quantum phase transition. In one-dimensional wires, the fluctuations of Cooper pairs appearing below the mean-field critical temperature Tc0 define a finite resistance via the nucleation of thermally activated phase slips, removing the finite temperature phase tran- sition. Superconductivity possibly survives only at zero temperature. -

Thermodynamics Notes

Thermodynamics Notes Steven K. Krueger Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Utah August 2020 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is thermodynamics? . .1 1.2 The atmosphere . .1 2 The Equation of State 1 2.1 State variables . .1 2.2 Charles' Law and absolute temperature . .2 2.3 Boyle's Law . .3 2.4 Equation of state of an ideal gas . .3 2.5 Mixtures of gases . .4 2.6 Ideal gas law: molecular viewpoint . .6 3 Conservation of Energy 8 3.1 Conservation of energy in mechanics . .8 3.2 Conservation of energy: A system of point masses . .8 3.3 Kinetic energy exchange in molecular collisions . .9 3.4 Working and Heating . .9 4 The Principles of Thermodynamics 11 4.1 Conservation of energy and the first law of thermodynamics . 11 4.1.1 Conservation of energy . 11 4.1.2 The first law of thermodynamics . 11 4.1.3 Work . 12 4.1.4 Energy transferred by heating . 13 4.2 Quantity of energy transferred by heating . 14 4.3 The first law of thermodynamics for an ideal gas . 15 4.4 Applications of the first law . 16 4.4.1 Isothermal process . 16 4.4.2 Isobaric process . 17 4.4.3 Isosteric process . 18 4.5 Adiabatic processes . 18 5 The Thermodynamics of Water Vapor and Moist Air 21 5.1 Thermal properties of water substance . 21 5.2 Equation of state of moist air . 21 5.3 Mixing ratio . 22 5.4 Moisture variables . 22 5.5 Changes of phase and latent heats . -

VISCOSITY of a GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, a N College, Patna

Lecture Note on VISCOSITY OF A GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, A N College, Patna A sketchy summary of the main points Viscosity of gases, relation between mean free path and coefficient of viscosity, temperature and pressure dependence of viscosity, calculation of collision diameter from the coefficient of viscosity Viscosity is the property of a fluid which implies resistance to flow. Viscosity arises from jump of molecules from one layer to another in case of a gas. There is a transfer of momentum of molecules from faster layer to slower layer or vice-versa. Let us consider a gas having laminar flow over a horizontal surface OX with a velocity smaller than the thermal velocity of the molecule. The velocity of the gaseous layer in contact with the surface is zero which goes on increasing upon increasing the distance from OX towards OY (the direction perpendicular to OX) at a uniform rate . Suppose a layer ‘B’ of the gas is at a certain distance from the fixed surface OX having velocity ‘v’. Two layers ‘A’ and ‘C’ above and below are taken into consideration at a distance ‘l’ (mean free path of the gaseous molecules) so that the molecules moving vertically up and down can’t collide while moving between the two layers. Thus, the velocity of a gas in the layer ‘A’ ---------- (i) = + Likely, the velocity of the gas in the layer ‘C’ ---------- (ii) The gaseous molecules are moving in all directions due= to −thermal velocity; therefore, it may be supposed that of the gaseous molecules are moving along the three Cartesian coordinates each. -

Viscosity of Gases References

VISCOSITY OF GASES Marcia L. Huber and Allan H. Harvey The following table gives the viscosity of some common gases generally less than 2% . Uncertainties for the viscosities of gases in as a function of temperature . Unless otherwise noted, the viscosity this table are generally less than 3%; uncertainty information on values refer to a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar) . The notation P = 0 specific fluids can be found in the references . Viscosity is given in indicates that the low-pressure limiting value is given . The dif- units of μPa s; note that 1 μPa s = 10–5 poise . Substances are listed ference between the viscosity at 100 kPa and the limiting value is in the modified Hill order (see Introduction) . Viscosity in μPa s 100 K 200 K 300 K 400 K 500 K 600 K Ref. Air 7 .1 13 .3 18 .5 23 .1 27 .1 30 .8 1 Ar Argon (P = 0) 8 .1 15 .9 22 .7 28 .6 33 .9 38 .8 2, 3*, 4* BF3 Boron trifluoride 12 .3 17 .1 21 .7 26 .1 30 .2 5 ClH Hydrogen chloride 14 .6 19 .7 24 .3 5 F6S Sulfur hexafluoride (P = 0) 15 .3 19 .7 23 .8 27 .6 6 H2 Normal hydrogen (P = 0) 4 .1 6 .8 8 .9 10 .9 12 .8 14 .5 3*, 7 D2 Deuterium (P = 0) 5 .9 9 .6 12 .6 15 .4 17 .9 20 .3 8 H2O Water (P = 0) 9 .8 13 .4 17 .3 21 .4 9 D2O Deuterium oxide (P = 0) 10 .2 13 .7 17 .8 22 .0 10 H2S Hydrogen sulfide 12 .5 16 .9 21 .2 25 .4 11 H3N Ammonia 10 .2 14 .0 17 .9 21 .7 12 He Helium (P = 0) 9 .6 15 .1 19 .9 24 .3 28 .3 32 .2 13 Kr Krypton (P = 0) 17 .4 25 .5 32 .9 39 .6 45 .8 14 NO Nitric oxide 13 .8 19 .2 23 .8 28 .0 31 .9 5 N2 Nitrogen 7 .0 12 .9 17 .9 22 .2 26 .1 29 .6 1, 15* N2O Nitrous -

Physics, Chapter 17: the Phases of Matter

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 17: The Phases of Matter Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 17: The Phases of Matter" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 165. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/165 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 17 The Phases of Matter 17-1 Phases of a Substance A substance which has a definite chemical composition can exist in one or more phases, such as the vapor phase, the liquid phase, or the solid phase. When two or more such phases are in equilibrium at any given temperature and pressure, there are always surfaces of separation between the two phases. In the solid phase a pure substance generally exhibits a well-defined crystal structure in which the atoms or molecules of the substance are arranged in a repetitive lattice. Many substances are known to exist in several different solid phases at different conditions of temperature and pressure. These solid phases differ in their crystal structure. Thus ice is known to have six different solid phases, while sulphur has four different solid phases. -

Qualitative Picture of Scaling in the Entropy Formalism

Entropy 2008, 10, 224-239; DOI: 10.3390/e10030224 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.org/entropy Article Qualitative Picture of Scaling in the Entropy Formalism Hans Behringer Faculty of Physics, University of Bielefeld, D-33615 Bielefeld, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Received: 30 June 2008; in revised form: 27 August 2008 / Accepted: 2 September 2008 / Published: 5 September 2008 Abstract: The properties of an infinite system at a continuous phase transition are charac- terised by non-trivial critical exponents. These non-trivial exponents are related to scaling relations of the thermodynamic potential. The scaling properties of the singular part of the specific entropy of infinite systems are deduced starting from the well-established scaling re- lations of the Gibbs free energy. Moreover, it turns out that the corrections to scaling are suppressed in the microcanonical ensemble compared to the corresponding corrections in the canonical ensemble. Keywords: Critical phenomena, microcanonical entropy, scaling relations, Gaussian and spherical model 1. Introduction In a mathematically idealised way continuous phase transitions are described in infinite systems al- though physical systems in nature or in a computer experiment are finite. The singular behaviour of physical quantities such as the response functions is related to scaling properties of the thermodynamic potential which is used for the formulation [1, 2]. Normally the Gibbs free energy is chosen for the description although other potentials also contain the full information about an equilibrium phase transi- tion. The Hankey-Stanley theorem relates the scaling properties of the Gibbs free energy to the scaling properties of any other energy-like potential that is obtained from the Gibbs free energy by a Legendre transformation [3]. -

Ionic Liquid and Supercritical Fluid Hyphenated Techniques for Dissolution and Separation of Lanthanides, Actinides, and Fission Products

Project No. 09-805 Ionic Liquid and Supercritical Fluid Hyphenated Techniques for Dissolution and Separation of Lanthanides, Actinides, and Fission Products ItIntegrat tdUied Universit itPy Programs Dr. Chien Wai University of Idaho In collaboration with: Idaho National Laboratory Jack Law, Technical POC James Bresee, Federal POC 1 Ionic Liquid and Supercritical Fluid Hyphenated Techniques For Dissolution and Separation of Lanthanides and Actinides DOE-NEUP Project (TO 00058) Final Technical Report Principal Investigator: Chien M. Wai Department of Chemistry, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho 83844 Date: December 1, 2012 2 Table of Contents Project Summary 3 Publications Derived from the Project 5 Chapter I. Introduction 6 Chapter II. Uranium Dioxide in Ionic Liquid with a TP-HNO3 Complex – Dissolution and Coordination Environment 9 1. Dissolution of UO2 in Ionic Liquid with TBP(HNO3)1.8(H2O)0.6 2. Raman Spectra of Dissolved Uranyl Species in IL 13 3. Transferring Uranium from IL Phase to sc-CO2 15 Chapter III. Kinetic Study on Dissolution of Uranium Dioxide and Neodymium Sesquioxide in Ionic Liquid 19 1. Rate of Dissolution of UO2 and Nd2O3 in RTIL 19 2. Temperature Effect on Dissolution of UO2 and Nd2O3 24 3. Viscosity Effect on Dissolution of UO2 in IL with TBP(HNO3)1.8(H2O)0.6 Chapter IV. Separation of UO2(NO3)2(TBP)2 and Nd(NO3)3(TBP)3 in Ionic Liquid Using Diglycolamide and Supercritical CO2 Extraction 30 1. Complexation of Uranyl with Diglycolamide TBDGA in Ionic Liquid 31 2. Complexation of Neodymium(III) with TBDGA in Ionic Liquid 35 3. Solubility and Distribution Ratio of UO2(NO3)2(TBP)2 and Nd(NO3)3(TBP)3 in Supercritical CO2 Phase 38 4. -

Chapter 3 Equations of State

Chapter 3 Equations of State The simplest way to derive the Helmholtz function of a fluid is to directly integrate the equation of state with respect to volume (Sadus, 1992a, 1994). An equation of state can be applied to either vapour-liquid or supercritical phenomena without any conceptual difficulties. Therefore, in addition to liquid-liquid and vapour -liquid properties, it is also possible to determine transitions between these phenomena from the same inputs. All of the physical properties of the fluid except ideal gas are also simultaneously calculated. Many equations of state have been proposed in the literature with either an empirical, semi- empirical or theoretical basis. Comprehensive reviews can be found in the works of Martin (1979), Gubbins (1983), Anderko (1990), Sandler (1994), Economou and Donohue (1996), Wei and Sadus (2000) and Sengers et al. (2000). The van der Waals equation of state (1873) was the first equation to predict vapour-liquid coexistence. Later, the Redlich-Kwong equation of state (Redlich and Kwong, 1949) improved the accuracy of the van der Waals equation by proposing a temperature dependence for the attractive term. Soave (1972) and Peng and Robinson (1976) proposed additional modifications of the Redlich-Kwong equation to more accurately predict the vapour pressure, liquid density, and equilibria ratios. Guggenheim (1965) and Carnahan and Starling (1969) modified the repulsive term of van der Waals equation of state and obtained more accurate expressions for hard sphere systems. Christoforakos and Franck (1986) modified both the attractive and repulsive terms of van der Waals equation of state. Boublik (1981) extended the Carnahan-Starling hard sphere term to obtain an accurate equation for hard convex geometries. -

Thermodynamics

ME346A Introduction to Statistical Mechanics { Wei Cai { Stanford University { Win 2011 Handout 6. Thermodynamics January 26, 2011 Contents 1 Laws of thermodynamics 2 1.1 The zeroth law . .3 1.2 The first law . .4 1.3 The second law . .5 1.3.1 Efficiency of Carnot engine . .5 1.3.2 Alternative statements of the second law . .7 1.4 The third law . .8 2 Mathematics of thermodynamics 9 2.1 Equation of state . .9 2.2 Gibbs-Duhem relation . 11 2.2.1 Homogeneous function . 11 2.2.2 Virial theorem / Euler theorem . 12 2.3 Maxwell relations . 13 2.4 Legendre transform . 15 2.5 Thermodynamic potentials . 16 3 Worked examples 21 3.1 Thermodynamic potentials and Maxwell's relation . 21 3.2 Properties of ideal gas . 24 3.3 Gas expansion . 28 4 Irreversible processes 32 4.1 Entropy and irreversibility . 32 4.2 Variational statement of second law . 32 1 In the 1st lecture, we will discuss the concepts of thermodynamics, namely its 4 laws. The most important concepts are the second law and the notion of Entropy. (reading assignment: Reif x 3.10, 3.11) In the 2nd lecture, We will discuss the mathematics of thermodynamics, i.e. the machinery to make quantitative predictions. We will deal with partial derivatives and Legendre transforms. (reading assignment: Reif x 4.1-4.7, 5.1-5.12) 1 Laws of thermodynamics Thermodynamics is a branch of science connected with the nature of heat and its conver- sion to mechanical, electrical and chemical energy. (The Webster pocket dictionary defines, Thermodynamics: physics of heat.) Historically, it grew out of efforts to construct more efficient heat engines | devices for ex- tracting useful work from expanding hot gases (http://www.answers.com/thermodynamics).