Tackling Lgbt Issues in Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Entire Issue As

Full schedule of PrideFest’s 25th anniver- sary events. Page 20 THE VOICE OF PROGRESS FOR WISCOnsin’s LGBT COMMUNITY May 31, 2012 | Vol. 3, No. 15 Today’s out gay military PHOTO: ADAM HORWITZ Navy group at Great Lakes boosts Pride, p. 4 NAACP: Mar- Countering anti- How Wisconsin Locals take Milwaukee’s gay Personal chefs riage equality is gay stigma in passed first gay center stage at Pride: A time- make outdoor a civil right, p. 6 Milwaukee, p. 8 rights law, p. 12 PrideFest, p. 19 line, p. 24 dining easy, p. 54 SHOW YOUR PRIDE AT THE POLLS – vOTE JUNE 5, P. 16 2 WISCONSINGAZETTE.COM | May 31, 2012 LGBT news with a twist WiGWAG By Lisa Neff & Louis Weisberg testant to compete Ohio, school district negoti- say to a student who is getting The industry, which is fighting in the Miss Uni- ated with Lambda Legal over bullied for being gay or lesbian?” standards to reduce harmful pol- verse Canada pag- a principal’s decision to ban a the organization asked in a state- lutants, advertised for the activ- eant reached the student from wearing a “Jesus ment. ists on Craigslist. penultimate round Is Not A Homophobe” T-shirt. before losing her The principal required the stu- BUT WHO IS SHE? PROUD DEBUT bid to win the title. Jenna dent to turn the shirt inside out You know the fight for equality Adam Lambert’s new album Talackova, 23, did leave the glitzy and ordered him not to wear it has reached a milestone when “Trespassing” debuted at No. -

National Day of Silence: the Freedom to Speak (Or Not) Frequently Asked Questions, Answered by Lambda Legal

National Day of Silence: The Freedom to Speak (Or Not) Frequently Asked Questions, Answered by Lambda Legal March 2018 April 27, 2018 is the National Day of Silence, a student-led action sponsored by the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) in which thousands of students around the country will remain silent for all or part of the school day to call attention to the harassment and discrimination faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth. Over the years, GLSEN and Lambda Legal have heard from hundreds of students, parents and allies who have encountered resistance from their schools and school officials in response to their efforts to participate in Day of Silence activities. The purpose of this FAQ is to provide information about the rights of students to participate in the Day of Silence and what to do if school officials interfere with those rights. Do students have the right to participate in and Do students have a right to display posters and advocate for the Day of Silence? make announcements about the Day of Silence? In most circumstances, yes. Under the Constitution, public In many circumstances, yes. If a public school generally schools must respect students’ right to free speech.1 The allows students or student organizations to display posters right to speak includes the right not to speak, as well as the or make announcements on the public address system—the right to wear buttons or T-shirts expressing support for a school may not deny or otherwise restrict your right to cause. This does not mean students can say—or not say— display posters or use the PA system based on your anything they want at all times. -

Trans Resources

Resources Duke Child and Adolescent Gender Care www.dukehealth.org TransActive, support for trans* children and families http://www.transactiveonline.org Tarheel Transmen online support group Charlotte Gender Alliance, support group http://charlottegenderalliance.info/ Gender Benders- Greenville Support and Activist Group GLBTQ http://genderbenderssc.org/GenderBenders/Welcome.html Palmetto Gender Association, connecting trans* folks with resources in South Carolina chapters http://www.palmettotgassociation.org/default.html PFLAG: PFLAG Flat Rock/Hendersonville http://community.pflag.org WNC Trans Support Hotline through Campaign for Southern Equality 237-1323 Phoenix Transgender Support Group (meet every 2 months) phoenixtgs.weebly.com/ Asheville Transformers http://tranzmission.org/transformers-support- groups.html YouthOUTright for GLBTQ youth, ages 14-23, youthoutright.org/ QORDS a camp For lgbtqqia youth and youth of lgbtqqia parents ages 11-17. Social Justice and Music camp with year round events. www.qords.org Western NC Community Health Services 285-0622, www.wncchs.org/ Asheville Planned Parenthood 252-7928, hormone therapy, education, referrals Beloved House Asheville Trans* affirming homelessness resource, 39 Grove St. 242-8261 Mission Hospital Speech Therapy, contact Patricia Handlon 213-0850 24/7 Suicide Prevention Hotline 1-800-273-8255 the Trevor Project 866-4-U-TREVOR (866-488-7386) wehappytrans.com: for sharing positive trans experiences Anne L. Boedecker, PhD, The Transgender Guidebook: Keys to a Successful Transition, -

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Identity Formation Michele J

1 Shifting Sands or Solid Foundation? Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Identity Formation Michele J. Eliason and Robert Schope 1 Introduction How do some individuals come to identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender? Is there a static, universal process of identity formation that crosses all lines of individual difference, such as sexual identities, sex/gender, class, race/ethnicity, and age? If so, can we describe that process in a series of linear stages or steps? Is identity based on a rock-solid foundation, stable and consistent over time? Or are there many identity formation processes that are specific to social and historical factors and/or individual differences, an ever- shifting landscape like a sand dune? The field of lesbian/gay/ bisexual/transgender (LGBT) studies is characterized by competing paradigms expressed in various ways: nature versus nurture, biology versus environment, and essentialism versus social constructionism (Eliason, 1996b). Although subtly different, all three debates share common features. Nature, biology, and essentialistic paradigms propose that sexual and gender identities are “real,” based in biology or very early life experiences and fixed and stable throughout the life span. These paradigms allow for the development of linear stages of development, or “coming out,” models. On the other hand, nurture, environment, and social constructionist paradigms point to sexual and gender identities as contingent on time and place, social circumstances, and historical period, thus suggesting that identities are flexible, vari- able, and mutable. “Queer theory” conceptualizations of gender and sexuality as fluid, “performative,” and based on social-historical con- texts do not allow for neat and tidy stage theories of identity develop- ment. -

Kevin Jennings Born: Winston-Salem, N.C

\ POSITION: ASSISTANT DEPUTY SECRETARY FOR THE OFFICE OF SAFE AND DRUG FREE SCHOOLS NOMINEE: Kevin Jennings Born: Winston-Salem, N.C. Occupation: Executive Director, and founder, of GLSEN, the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. Education: graduated magna cum laude from Harvard College View of Christians Addressing a church audience on March 20, 2000 in New York City — just days before "Fistgate" — GLSEN Executive Director Kevin Jennings offered a stinging (and quite intolerant) assessment of how to deal with religious conservatives: Twenty percent of people are hard-core fair-minded [pro-homosexual] people. Twenty percent are hard-core [anti-homosexual] bigots. We need to ignore the hard-core bigots, get more of the hard-core fair-minded people to speak up, and we'll pull that 60 percent [of people in the middle] … over to our side. That's really what I think our strategy has to be. We have to quit being afraid of the religious right. We also have to quit — … I'm trying to find a way to say this. I'm trying not to say, '[F---] 'em!' which is what I want to say, because I don't care what they think! [audience laughter] Drop dead! It should be noted that GLSEN and Jennings make heavy use of the words "respect" and "tolerance" in their public rhetoric and in descriptions of their programs. [ Source ] GLSEN and “Fistgate” GLSEN, which promotes homosexual clubs and the homosexual lifestyle in high schools, middle schools and grade schools and is the driving force behind the annual "Day of Silence" celebration of homosexuality “The most notorious education scandal involving homosexual activists is a GLSEN- sponsored conference that occurred on March 25, 2000, dubbed ‘Fistgate’ by conservatives. -

Culturally Competent Mental Health Care for Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender and Questioning

COD Treatment WA State Conference Yakima, WA October 6th & 7th, 2014 Culturally Competent Mental Health Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Questioning (LGBTQ) Clients Donnie Goodman NCC/MA LMHP Deputy Director, Seattle Counseling Service The following are a combination of what will be covered during the 8:30 am Keynote on Tuesday, October 7th, 2014 and Workshop Session 5 from 1:45 – 3:00, Tuesday, October 7th, 2014. Part 1: Introduction to the Gay World • Introduction: • Sexual minorities are one of only two minority groups not born into their minority: . Sexual minorities . Handicapped- physical and emotional . Sexual Minorities – use of the word “Queer” • Washington State Psychological Association • Reparative/Conversion Therapy • Definitions: Common terms • Homophobia • Internalized Homophobia • Gay History • Assumptions Part 2: Life • Coming out Stages • Psychological Issues Related to Coming Out • Aspects of Coming Out • Questions to Consider When Coming Out • Coping Mechanisms for Gay Youth • Strategies for Engagement • Working With Families • Religion • Same-sex Relationships • Domestic Violence • Discussing Safe Sex: AIDS; STD’s Part 3: Therapeutic Focus and Resources • Strategies for Effective Treatment • Inclusive Language • Differential Diagnosis o PTSD o Others • Preventing/Reducing Harassment • Increasing Cultural Competence – Heterosexual Lifestyle Questionnaire • Your Organization; Your Forms/Paperwork • Resources Extra Items in the Packet • Personal Assessment of Homophobia • In-depth Description of Homophobia -

Curriculum & Action Guide

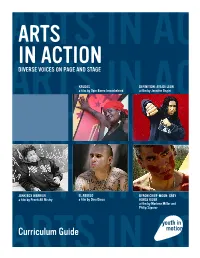

DVD TITLE ARTSARTSFacilitating a Discussion IN AC IN ACTION Finding a Facilitator DIVERSE VOICES ON PAGE AND STAGE KRUDAS DEFINITION: AYA DE LEON Identify your own. When the 90’s hit,a all film the by Opie Boero ImwinkelriedIdentify your own. Whena film the by Jennifer 90’s hit, Ongiri all the new communication technologies offered new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate that was people a new way to communicate that was ARTSeasier and more. INeasier and more. AC Be knowledgeable. When the 90’s hit, all the Be knowledgeable. When the 90’s hit, all the new communication technologies offered new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate that was people a new way to communicate that was easier and more. easier and more. Be clear about your role. When the 90’s hit, Be clear about your role. When the 90’s hit, all the new communication technologies all the new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate offered people a new way to communicate ARTSthat was easier and more. INthat was easier and more. AC Know your group. When the 90’s hit, all the Know your group. When the 90’s hit, all the new communication technologies offered new communication technologies offered people a new way to communicate that was people a new way to communicate that was easier and more. easier and more. JUNK BOX WARRIOR EL ABUELO BYRON CHIEF-MOON: GREY a film by Preeti AK Mistry a film by Dino Dinco HORSE RIDER a film by Marlene Millar and ARTS INPhilip SzporerAC Curriculum Guide ARTS INwww.frameline.org/distribution -

Pride Politics: a Socio-Affective Analysis by Randi Nixon a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For

Pride Politics: A Socio-Affective Analysis by Randi Nixon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Sociology University of Alberta ©Randi Nixon, 2017 ii Abstract: This dissertation explores the affective politics of pride in the context of neoliberalism and the multitude of way that proud feelings map onto issues of social justice. Since pride is so varied in both its individual and political manifestations, I draw on numerous instances of collective pride to attend to the relational, structural and historical contours of proud feelings. Given the methodological challenges posed by affect, I use a mixed- method approach that includes interviews, participant observation, and discourse analysis, while being keenly attuned to the tension between bodily materiality and discursivity. Each chapter attends to an “event” of pride, exploring its emergence during particular encounters with collective difference. The project fills a gap in affect theory by attending to the way that proud feelings play a vital role in both igniting the political intensity necessary to bring about change (through Pride politics), and blocking or extinguishing possibilities of respectful dialogue and solidarity across gendered, sexual, and racial difference. Across the chapters, pride is used as a conduit through which the complexity of affective politics can be examined. The proud events around and through which each chapter is structured expose paths of affect and its politics. Taken together, the chapters provide an initial blueprint for navigating contemporary affective politics. Through an examination of the discursive rendering of pride, I find that, across several literatures, two key characteristics of pride are its deep relationality between individuals and collectives, and the way it circulates, is managed, and emerges in relation to social hierarches and the value attached to political categories (race, class, gender, ability). -

WBFSH Eventing Breeder 2020 (Final).Xlsx

LONGINES WBFSH WORLD RANKING LIST - BREEDERS OF EVENTING HORSES (includes validated FEI results from 01/10/2019 to 30/09/2020 WBFSH member studbook validated horses) RANK BREEDER POINTS HORSE (CURRENT NAME / BIRTH NAME) FEI ID BIRTH GENDER STUDBOOK SIRE DAM SIRE 1 J.M SCHURINK, WIJHE (NED) 172 SCUDERIA 1918 DON QUIDAM / DON QUIDAM 105EI33 2008 GELDING KWPN QUIDAM AMETHIST 2 W.H. VAN HOOF, NETERSEL (NED) 142 HERBY / HERBY 106LI67 2012 GELDING KWPN VDL ZIROCCO BLUE OLYMPIC FERRO 3 BUTT FRIEDRICH 134 FRH BUTTS AVEDON / FRH BUTTS AVEDON GER45658 2003 GELDING HANN HERALDIK XX KRONENKRANICH XX 4 PATRICK J KEARNS 131 HORSEWARE WOODCOURT GARRISON / WOODCOURT GARRISON104TB94 2009 MALE ISH GARRISON ROYAL FURISTO 5 ZG MEYER-KULENKAMPFF 129 FISCHERCHIPMUNK FRH / CHIPMUNK FRH 104LS84 2008 GELDING HANN CONTENDRO I HERALDIK XX 6 CAROLYN LANIGAN O'KEEFE 128 IMPERIAL SKY / IMPERIAL SKY 103SD39 2006 MALE ISH PUISSANCE HOROS 7 MME SOPHIE PELISSIER COUTUREAU, GONNEVILLE SUR127 MER TRITON(FRA) FONTAINE / TRITON FONTAINE 104LX44 2007 GELDING SF GENTLEMAN IV NIGHTKO 8 DR.V NATACHA GIMENEZ,M. SEBASTIEN MONTEIL, CRETEIL124 (FRA)TZINGA D'AUZAY / TZINGA D'AUZAY 104CS60 2007 MARE SF NOUMA D'AUZAY MASQUERADER 9 S.C.E.A. DE BELIARD 92410 VILLE D AVRAY (FRA) 122 BIRMANE / BIRMANE 105TP50 2011 MARE SF VARGAS DE STE HERMELLE DIAMANT DE SEMILLY 10 BEZOUW VAN A M.C.M. 116 Z / ALBANO Z 104FF03 2008 GELDING ZANG ASCA BABOUCHE VH GEHUCHT Z 11 A. RIJPMA, LIEVEREN (NED) 112 HAPPY BOY / HAPPY BOY 106CI15 2012 GELDING KWPN INDOCTRO ODERMUS R 12 KERSTIN DREVET 111 TOLEDO DE KERSER -

True Colors Resource Guide

bois M gender-neutral M t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois gender-neutral M gender-neutralLOVEM gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch Birls polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme Asexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois M gender-neutral gender-neutral M t t F F ALLY Lesbian INTERSEX butch INTERSEXALLY Birls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer bisexual Asexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual bi-curious bi-curious transsexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bois bois LOVE gender-neutral M gender-neutral t F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident pansexualtranssexual bois bois M gender-neutral M gender-neutral t t F F INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch INTERSEXALLY Lesbian butch polyamorousBirls polyamorousBirls queer Femme queer Femme bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bisexual GAY GrrlsAsexual bi-curious bi-curious QUEstioningtransgender bi-confident -

In “The Tenement Windows”

Contact: Jas Chana, Media & Communications Manager, [email protected], 646-518-3063 October 25, 2018, New York, NY— Kevin Jennings, the President of the Tenement Museum, has been named no.2 on OUTstanding’s 2018 global list of top 30 LGBT+ Public Sector Executives. Jennings was chosen by OUTStanding, a membership organization dedicated to promoting diversity & inclusion in the workplace, for his three decades of leadership in the global LGBT+ movement, which continues now in his role as Tenement Museum President. Launched in 2013, the annual list is one of several that comprise OUTstanding’s #OUTRoleModels18 campaign, which celebrates executives and leaders across the public and private sectors who are helping to make their workplace more welcoming, and who are making a significant contribution to LGBT+ inclusion outside of their workplace. The campaign is sponsored by the Financial Times. Jennings contributions to the LGBT+ movements began in 1988 when he created the first school-based Gay-Straight Alliance club, leading him to found and lead the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN) for 18 years. He then served as an Assistant Secretary of Education for President Obama, after which he ran the Arcus Foundation, the world’s largest funder of LGBT rights organizations, for 5 years. In July 2017 Jennings joined the Tenement Museum, one of New York’s premier educational and cultural institutions dedicated to telling the uniquely American stories of immigrants, migrants and refuges in the ongoing creation of the United States. Since then, Jennings has launched an ambitious strategic plan aimed at dramatically increasing the institution’s reach and impact over the next five years with the goal of reshaping the national narrative about immigration at a time when the issue is front page news. -

2020-2021 Calendar

2020-2021 CALENDAR www.gsanetwork.org REGISTER YOUR GSA every year to receive resources, news, and information to strengthen your GSA club! Be sure to add your advisor and club leaders’ This names and contact information: www.gsanetwork.org/gsa-registration/ Month Get free LGBTQ+ films for your GSA to watch as a group! Register for Youth in September Motion: www.frameline.org/youth-motion 2020 LGBTQ+ LATINX HISTORY MONTH th Sep 15 - Celebrate the accomplishments of LGBTQ+ Latinx figures, like trans activist Oct 15th Sylvia Rivera & undocumented trans activist Jennicet Gutiérrez. Find more ideas on how to uplift LGBTQ+ Latinx activists in ourresource library. This LGBTQ+ HISTORY MONTH Celebrate by teaching your school about our community’s history: Month www.gsanetwork.org/resources/lgbt-history-month/ ALLY WEEK October th th This youth-led weeklong event aims to shed light on the experiences of 2020 5 -9 LGBTQ+ students in schools. Challenge and invite straight cisgender students and adults to build support with LGBTQ+ youth in their communities. INTERSEX AWARENESS DAY th This international day of awarness marks the anniversary of the first intersex 26 protest in the United States in 1996. Check out resources from InterAct: www.interactadvocates.org/intersex-awareness-day/ This LGBTQ+ NATIVE AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH Celebrate and uplift the accomplishments of historical and contemporary Month LGBTQ+ Native American figures. November 2020 INTERSEX DAY OF SOLIDARITY th Today marks Herculine Barbin’s birthday, a French intersex person whose 8 memoirs were published posthumously. Show your solidarity by honoring historical and contemporary intersex activists & writers. GSA DAY FOR GENDER JUSTICE - #GSADay4GJ This is an annual day of action to mobilize for gender justice & celebrate the 13th multiple identities LGBTQ+ youth embody.