Towards a Caribbean Cinema – Can There Be Or Is There A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

Crítica De Cinema Na África

CINEMAS AFRICANOS CONTEMPORÂNEOS Abordagens Críticas SESC – SERVIÇO SOCIAL DO COMÉRCIO Administração Regional no Estado de São Paulo PRESIDENTE DO CONSELHO REGIONAL Abram Szajman DIRETOR DO DEPARTAMENTO REGIONAL Danilo Santos de Miranda SUPERINTENDENTES Técnico-Social Joel Naimayer Padula Comunicação Social Ivan Giannini Administração Luiz Deoclécio Massaro Galina Assessoria Técnica e de Planejamento Sérgio José Battistelli GERENTES Ação Cultural Rosana Paulo da Cunha Estudos e Desenvolvimento Marta Raquel Colabone Assessoria de Relações Internacionais Aurea Leszczynski Vieira Gonçalves Artes Gráficas Hélcio Magalhães Difusão e Promoção Marcos Ribeiro de Carvalho Digital Fernando Amodeo Tuacek CineSesc Gilson Packer CINE ÁFRICA 2020 Equipe Sesc Cecília de Nichile, Cesar Albornoz, Érica Georgino, Fernando Hugo da Cruz Fialho, Gabriella Rocha, Graziela Marcheti, Heloisa Pisani, Humberto Motta, João Cotrim, Karina Camargo Leal Musumeci, Kelly Adriano de Oliveira, Ricardo Tacioli, Rodrigo Gerace, Simone Yunes Curadoria e direção de produção e comunicação: Ana Camila Esteves Assistente de produção: Edmilia Barros Produção técnica: Daniel Petry Identidade visual, projeto gráfico e capa: Jéssica Patrícia Soares Assessoria de imprensa: Isidoro Guggiana Traduções e legendas: Casarini Produções Revisão: Ana Camila Esteves e Jusciele Oliveira CINEMAS AFRICANOS CONTEMPORÂNEOS Abordagens Críticas Ana Camila Esteves Jusciele Oliveira (Orgs.) São Paulo, Sesc 2020 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) C4909 Cinemas africanos contemporâneos: abordagens críticas / Ana Camila Esteves; Jusciele Oliveira (orgs.). – São Paulo: Sesc, 2020. – 1 ebook; xx Kb; e-PUB. il. – Bibliografia ISBN: 978-65-89239-00-0 1. Cinema africano. 2. Cine África. 3. Crítica. 4. Mostra de filmes. 5. Mostra virtual de filmes. 6. Publicações sobre cinema africano no Brasil e no mundo. I. Título. -

PDF Download a Dry White Season Ebook Free

A DRY WHITE SEASON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andre Brink | 316 pages | 31 Aug 2011 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780061138638 | English | New York, NY, United States A Dry White Season PDF Book There are no race relations. Marlon Brando as McKenzie. Detroit: Gale Research, From metacritic. What does he think life is like there? There are so many passages that resonate with the barriers, pitfalls and depressing realities that never seem to change when fighting for a better world against incredible resistance and hatred: When the system is threatened they will do anything to defend it It's not cynicism, it's reality I just want to go back to the way things were Don't you think they would do the same to us if they had the chance. In this process the marriage dissolves. Thompson, Leonard. Police show up at the house with some regularity—to question the Du Toits, to search the house, and ultimately to threaten them. Cry, the Beloved Country. Susan Sarandon plays a sympathetic journalist, and Marlon Brando, in a juicy comeback cameo that evokes Orson Welles's Clarence Darrow impersonation in Compulsion , plays an antiapartheid lawyer. How can scenes of torture and of the death of children not? Afrikaner —the former term was Boer —refers to whites who descend mainly from the early Dutch but also from the early German and French settlers in the region. Trailers and Videos. It's filled with beautiful beaches, abundant wildlife, lush rainforest, lovely waterfalls and dozens of volcanos. In the book the image is rooted in a specific event. -

Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

DIRECTORS WINNER FORTNIGHT BEST FEATURE CANNES PAN-AFRICAN FILM 2000 FESTIVAL L.A. A FILM BY RAOUL PECK A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE JACQUES BIDOU presents A FILM BY RAOUL PECK Patrice Lumumba Eriq Ebouaney Joseph Mobutu Alex Descas Maurice Mpolo Théophile Moussa Sowié Joseph Kasa Vubu Maka Kotto Godefroid Munungo Dieudonné Kabongo Moïse Tshombe Pascal Nzonzi Walter J. Ganshof Van der Meersch André Debaar Joseph Okito Cheik Doukouré Thomas Kanza Oumar Diop Makena Pauline Lumumba Mariam Kaba General Emile Janssens Rudi Delhem Director Raoul Peck Screenplay Raoul Peck Pascal Bonitzer Music Jean-Claude Petit Executive Producer Jacques Bidou Production Manager Patrick Meunier Marianne Dumoulin Director of Photography Bernard Lutic 1st Assistant Director Jacques Cluzard Casting Sylvie Brocheré Artistic Director Denis Renault Art DIrector André Fonsny Costumes Charlotte David Editor Jacques Comets Sound Mixer Jean-Pierre Laforce Filmed in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Belgium A French/Belgian/Haitian/German co-production, 2000 In French with English subtitles 35mm • Color • Dolby Stereo SRD • 1:1.85 • 3144 meters Running time: 115 mins A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE 247 CENTRE ST • 2ND FL • NEW YORK • NY 10013 www.zeitgeistfilm.com • [email protected] (212) 274-1989 • FAX (212) 274-1644 At the Berlin Conference of 1885, Europe divided up the African continent. The Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. On June 30, 1960, a young self-taught nationalist, Patrice Lumumba, became, at age 36, the first head of government of the new independent state. He would last two months in office. This is a true story. SYNOPSIS LUMUMBA is a gripping political thriller which tells the story of the legendary African leader Patrice Emery Lumumba. -

Feature • the Worst Movie Ever!

------------------------------------------Feature • The Worst Movie Ever! ----------------------------------------- Glenn Berggoetz: A Man With a Plan By Greg Locke with the film showing in L.A., with the name of the film up line between being so bad that something’s humorous and so on a marquee, at least a few dozen people would stop in each bad it’s just stupid. [We shot] The Worst Movie Ever! over The idea of the midnight movie dates back to the 1930s night to see the film. As it turned out, the theater never put the course of two days – a weekend. I love trying to do com- when independent roadshows would screen exploitation the title of the film up on the marquee, so passers-by were pletely bizarre, inane things in my films but have the charac- films at midnight for the sauced, the horny and the lonely. not made aware of the film screening there. As it turned out, ters act as if those things are the most natural, normal things The word-of-mouth phenomenon really began to hit its only one man happened to wander into the theater looking to in the world.” stride in the 50s when local television stations would screen see a movie at midnight who decided that a film titled The Outside of describing the weird world of Glenn Berg- low-budget genre films long after all the “normal” people Worst Movie Ever! was worth his $11. goetz, the movie in question is hard to give an impression of were tucked neatly into bed. By the 1970s theaters around “When I received the box office number on Monday, I with mere words. -

Iacs2017 Conferencebook.Pdf

Contents Welcome Message •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Conference Program •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 Conference Venues ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 Keynote Speech ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Plenary Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 20 Special Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 34 Parallel Sessions •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 40 Travel Information •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 228 List of participants ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 232 Welcome Message Welcome Message Dear IACS 2017 Conference Participants, I’m delighted to welcome you to three exciting days of conferencing in Seoul. The IACS Conference returns to South Korea after successful editions in Surabaya, Singapore, Dhaka, Shanghai, Bangalore, Tokyo and Taipei. The IACS So- ciety, which initiates the conferences, is proud to partner with Sunkonghoe University, which also hosts the IACS Con- sortium of Institutions, to organise “Worlding: Asia after/beyond Globalization”, between July 28 and July 30, 2017. Our colleagues at Sunkunghoe have done a brilliant job of putting this event together, and you’ll see evidence of their painstaking attention to detail in all the arrangements -

Negritude Or Black Cultural Nationalism

REVIEWS TM Journal of Modem African Studies, 3,3 (1965), pp. 321-48 From French West Africa to the Mali Federation by W1LLIAMj. FOLTZ PAUL SEMONIN, Dakar, Sencgal 443 Negritude or Black Cultural Nationalism Tunisia Since Independence by CLEMENT HENR y Moo RE DR IMMANUEL WALLERSTEIN, Department ofSociology, Columbia Universi!)!, by ABIOLA IRELE* New rork 444 Th Modem Histo,;y ofSomali/and by I. M. LEWIS DR SAADIA TOUVAL, Institute of Asian and African Studies, Th Hebrew IT is well known that nationalist movements are generally accompanied Universi':)I ofJerusalem, ISTael 445 by parallel movements of ideas that make it possible for its leaders to The Foreign Policy ofAfrican States by DouDou TH JAM mould a new image of the dominated people. And as Thomas Hodgkin DR OEORGE o. ROBERTS, Dillision of Area Studies and Geography, Stat, has shown, the need for African political movements to 'justify them Universi!)! College, New Paltz, New rork 447 selves' and 'to construct ideologies' has been particularly strong. 1 Panafrika: Kontincntal, W,ltmacht im Werden? by HANSPETER F. STRAUCH Nationalist movements were to a large extent founded upon emotional Sociologie de la nouvelle Afrique by JEAN ZIEGLER DR FRANZ ANSPRENOER, Otto-Suhr-Institut an der Freien Unwersitiit Berlin impulses, which imparted a distinctive tone to the intellectual clamour The Economics ofSubsistence Agriculture by COLIN CLARK and M. R . HASWELL that went with them and which continue to have a clear resonance · JUNE KNOWLES, 1718 Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd., Nairobi 451 after independence. Uncqual Partners by THOMAS BALOGH In order to understand certain aspects of African nationalism and Foreign Trade and Economic Development in Africa by S. -

Wavelength (April 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1981 Wavelength (April 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1981) 6 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL 1 981 VOLUME 1 NUMBE'J8. OLE MAN THE RIVER'S LAKE THEATRE APRIL New Orleans Mandeville, La. 6 7 8 9 10 11 T,HE THE THIRD PALACE SUCK'S DIMENSION SOUTH PAW SALOON ROCK N' ROLL Baton Rouge, La. Shreveport. La. New Orleans Lalaye"e, La. 13 14 15 16 17 18 THE OLE MAN SPECTRUM RIVER'S ThibOdaux, La. New Orleans 20 21 22 23 24 25 THE LAST CLUB THIRD HAMMOND PERFORMANCE SAINT DIMENSION SOCIAL CLUB OLE MAN CRt STOPHER'S Baton Rouge, La. Hammond, La. RIVER'S New Orleans New Orleans 27 29 30 1 2 WEST COAST TOUR BEGINS Barry Mendelson presents Features Whalls Success? __________________6 In Concert Jimmy Cliff ____________________., Kid Thomas 12 Deacon John 15 ~ Disc Wars 18 Fri. April 3 Jazz Fest Schedule ---------------~3 6 Pe~er, Paul Departments April "Mary 4 ....-~- ~ 2 Rock 5 Rhylhm & Blues ___________________ 7 Rare Records 8 ~~ 9 ~k~ 1 Las/ Page _ 8 Cover illustration by Rick Spain ......,, Polrick Berry. Edllor, Connie Atkinson. -

Cartographie De L'industrie Haïtienne De La Musique

CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE DE LA MUSIQUE Organisation Diversité des Nations Unies des expressions pour l’éducation, culturelles la science et la culture Merci à tous les professionnels de la musique en Haïti et en diaspora qui ont accepté de prendre part à cette enquête et à tous ceux qui ont participé aux focus groups et à la table ronde. Merci à toute l’équipe d’Ayiti Mizik, à Patricio Jeretic, Joel Widmaier, Malaika Bécoulet, Mimerose Beaubrun, Ti Jo Zenny et à Jonathan Perry. Merci au FIDC pour sa confiance et d’avoir cru à ce projet. Cette étude est imprimée gracieusement grâce à la Fondation Lucienne Deschamps. Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie Textes : Pascale Jaunay (Ayiti Mizik) | Isaac Marcelin (Ayiti Nexus) | Philippe Bécoulet (Leos) Graphisme : Ricardo Mathieu, Joël Widmaier (couverture) Editing: Ricardo Mathieu, Milena Sandler Crédits photos couverture : Josué Azor, Joël Widmaier Firme d’enquête et focus group : Ayiti Nexus Tous droits réservés de reproduction des textes, photos et graphiques réservés pour tous pays ISBN : 978-99970-4-697-0 CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE LA MUSIQUE Dépot Légal : 1707-465 2 Imprimé en Haïti CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE DE LA MUSIQUE Organisation Diversité des Nations Unies des expressions pour l’éducation, culturelles la science et la culture CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE LA MUSIQUE 3 SOMMAIRE I. INTRODUCTION 8 A. CONTEXTE DU PROJET 8 B. OBJECTIFS 8 C. JUSTIFICATION 9 D. MÉTHODOLOGIE 10 1. Enquêtes de terrain 10 2. Focus groups 13 3. Analyse des résultats 13 4. Interviews 14 5. Table-ronde nationale 14 II. -

M a Dry White Season

A DRY WHITE SEASON ade in 1989, A Dry White Season , things straight. He hires a lawyer, Ian this first ever release of the score, we used a searing indictment of South Africa Mackenzie (Brando), a human rights attor - only score cues and those cues are as they Munder apartheid , was a superb, riv - ney who knows the case is hopeless but were originally written and recorded. The eting film that audiences simply did not who takes it on anyway. The case is dis - film order worked beautifully in terms of dra - want to see, despite excellent reviews. Per - missed, more people die, Du Toit is threat - matic and musical flow. We’ve included two haps it was because South Africa was still ened, he is abetted in his political bonus tracks – alternate versions of two in the final throes of apartheid and the film awakening by a reporter (Susan Sarandon), cues, which bring the musical presentation was just too uncomfortable to watch. Some - has his garage bombed, and has his wife to a very satisfying conclusion. times people need distance and one sus - and daughter turn against him. Only his pects that if the film had come out even a young son knows that what Du Toit is trying Dave Grusin is one of those composers decade later it would have probably been to do is right. Eventually, gathering affidavits who can do everything. And he has – from more successful. As it is, over the years from many people, he is able to outwit the dramatic film scoring to his great work in tel - people have discovered it and been truly af - secret police and have the documents de - evision (It Takes A Thief, Maude, Good fected by its portrayal of racial turmoil in a livered to a newspaper, but in the end it Times, Baretta, The Name Of The Game, country divided and the way the film was does no real good. -

Catalogue2007.Pdf

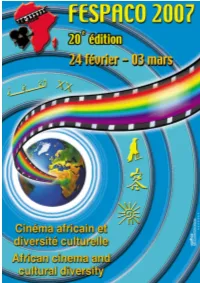

Sommaire / Contents Comité National d'Organisation / The National Organising Committee 6 Mot du Ministre de la Culture des Arts et du Tourisme / Speech of the Minister of Culture, Arts and Tourism 7 Mot du président d'honneur / Speech of honorary chairperson 8 Mot du Président du Comité d'Organisation / Speech of the President of the Organising Committee 9 Mot du Président du Conseil d’Administration / / Speech of the President of Chaireperson of the Board of Adminsitration 11 Mot du Maire de la ville de Ouagadougou / Speech of the Mayor of the City of Ouagadougou 12 Mot du Délégué Général du Fespaco / Speech of the General Delegate of Fespaco 13 Regard sur Manu Dibango, président d'honneur du 20è festival / Focus on Manu Dibango, Chair of Honor 15 Film d'Ouverture / Opening film 19 Jury longs métrages / Feature film jury 22 Liste compétition longs métrages / Competing feature films 24 Compétition longs métrages / Feature film competition 25 Jury courts métrages et films documentaires / Short and documentary film jury 37 Liste compétition courts métrages / Competing short films 38 Compétition courts métrages / Short films competition 39 Liste compétition films documentaires / Competing documentary films 49 Compétition films documentaires / Documentary films competition 50 3 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 59 Panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 60 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique courts métrages / Panorama -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence.