Where Has Rotuman Culture Gone? and What Is It Doing There?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotuman Educational Resource

Fäeag Rotuam Rotuman Language Educational Resource THE LORD'S PRAYER Ro’ạit Ne ‘Os Gagaja, Jisu Karisto ‘Otomis Ö’fāat täe ‘e lạgi, ‘Ou asa la ȧf‘ȧk la ma’ma’, ‘Ou Pure'aga la leum, ‘Ou rere la sok, fak ma ‘e lạgi, la tape’ ma ‘e rȧn te’. ‘Äe la nāam se ‘ạmisa, ‘e terạnit 'e ‘i, ta ‘etemis tē la ‘ā la tạu mar ma ‘Äe la fạu‘ạkia te’ ne ‘otomis sara, la fak ma ne ‘ạmis tape’ ma rē vạhia se iris ne sar ‘e ‘ạmisag. ma ‘Äe se hoa’ ‘ạmis se faksara; ‘Äe la sại‘ạkia ‘ạmis ‘e raksa’a, ko pure'aga, ma ne’ne’i, ma kolori, mou ma ke se ‘äeag, se av se ‘es gata’ag ne tore ‘Emen Rotuman Language 2 Educational Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY 4 ROGROG NE ROTUMA 'E 'ON TẠŪSA – Our history 4 'ON FUẠG NE AS TA ROTUMA – Meaning behind Rotuma 5 HẠITOHIẠG NE FUẠG FAK PUER NE HANUA – Chiefly system 6 HATAG NE FĀMORI – Population 7 ROTU – Religion 8 AGA MA GARUE'E ROTUMA – Lifestyle on the island 8 MAK A’PUMUẠ’ẠKI(T) – A treasured song 9 FŪ’ÅK NE HANUA GEOGRAPHY 10 ROTUMA 'E JAJ(A) NE FITI – Rotuma on the map of Fiji 10 JAJ(A) NE ITU ’ HIFU – Map of the seven districts 11 FÄEAG ROTUẠM TA LANGUAGE 12 'OU ‘EA’EA NE FÄEGA – Pronunciation Guide 12-13 'ON JĪPEAR NE FÄEGA – Notes on Spelling 14 MAF NE PUKU – The Rotuman Alphabet 14 MAF NE FIKA – Numbers 15 FÄEAG ‘ES’ AO - Useful words 16-18 'OU FÄEAG’ÅK NE 'ÄE – Introductions 19 UT NE FAMORI A'MOU LA' SIN – Commonly Frequented Places 20 HUẠL NE FḀU TA – Months of the year 21 AG FAK ROTUMA CULTURE 22 KATO’ AGA - Traditional ceremonies 22-23 MAMASA - Welcome Visitors and returnees 24 GARUE NE SI'U - Artefacts 25 TĒFUI – Traditional garland 26-28 MAKA - Dance 29 TĒLA'Ā - Food 30 HANUJU - Storytelling 31-32 3 ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY Legend has it that Rotuma’s first inhabitants Consequently, the two religious groups originated from Samoa led by Raho, a chief, competed against each other in the efforts to followed by the arrival of Tongan settlers. -

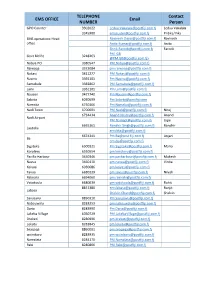

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Richard Feinberg, Ed., Seafaring in the Contemporary Pacific Islands: Studies in Continuity and Change

reviews Page 121 Monday, February 12, 2001 2:29 PM Reviews 121 Richard Feinberg, ed., Seafaring in the Contemporary Pacific Islands: Studies in Continuity and Change. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1995. Pp. 245, illus. US$35 cloth. Reviewed by Nicholas J. Goetzfridt, University of Guam There has been an interesting as well as a tired dichotomy of thinking about “voyaging” in the Pacific. Interesting because of questions concerned with the ability of voyagers to control their efforts across vast areas of a watery space in order to reach land and, in the settlement eras, to successfully prosper and possibly engage in return voyages of communication. These speculations, attempts at documentation through the paucity of European references to these voyagers, and the practical experiments undertaken by David Lewis and Ben Finney are all concerned with what must be seen as incredible journeys, regardless of how they were actually achieved. The thinking has been tired because of a habitual practice in all kinds of literature, both scholarly and popular, to assign an either/or identity to “voy- aging.” As we are occasionally told in comments usually tucked away in the bowels of some greater concern with modernity, this voyaging, for all its illus- trious past, is now “dead.” And as such, it wallows in the past. It is only the romantics, the individuals pricked by a yearning for the spectacular, who resist recognizing this foundational fact of Pacific life. Outboard motors and jet planes have nothing to do with this heritage. It is a loss basic to “contact” reviews Page 122 Monday, February 12, 2001 2:29 PM 122 Pacific Studies, Vol. -

Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change

The I and the We: Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change April K Henderson That the Samoan sense of self is relational, based on socio-spatial rela- tionships within larger collectives, is something of a truism—a statement of such obvious apparent truth that it is taken as a given. Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi, a former prime minister and current head of state of independent Sāmoa as well as an influential intellectual and essayist, has explained this Samoan relational identity: “I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a ‘tofi’ (an inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging” (Tui Atua 2003, 51). Elaborations of this relational self are consistent across the different political and geographical entities that Samoans currently inhabit. Par- ticipants in an Aotearoa/New Zealand–based project gathering Samoan perspectives on mental health similarly described “the Samoan self . as having meaning only in relationship with other people, not as an individ- ual. This self could not be separated from the ‘va’ or relational space that occurs between an individual and parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and other extended family and community members” (Tamasese and others 2005, 303). -

4.3 Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List

4.3 Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Port Name Company Physical Address Website & Email Phone Number (office & Fa Description of Duties mobile) x N u m ber All Fiji Fiji Ports n/a http://www.portofsuva. +679 6662160 +6 Port Management Ports Corporation com 79 Limited 66 65 799 All Bollore 8-9 Freeston Road, Walu Bay, Chandima +679 3315044 +6 Transporter, shipping, storage: (Pacific Logistics Suva, Fiji Gunawardana, General 79 Island (Fiji) Ltd Manager. chandima. Shipping: MV Internatio gunawardana@bollor e. 33 nal Ports) com 15 Subritzky 120 MT, cargo capacity. MV, 055 Kusima 110 MT, cargo capacity MV, Mobile: +679 9994869 Kawai 115 MT, cargo capacity Ronald Dass, Manager Operations. Ronald [email protected] Mobile: +679 9905910 All (Fiji Fiji Ports n/a http://www.portofsuva. +679 6662160 +6 Port Management Ports) Corporation com 79 Limited 66 65 799 All / Suva Government Governments Wharf iliesa. Freight Superintendent: Mr. n Govt Only Shipping Shipping [email protected] Iliesa Raketekete /a Services Off Amra Street, Walu Bay, http://www. (GSS) Suva governmentshipping.gov. Tel: +679 3312246 fj Mobile: +6793314561 Port of Sea Road Fiji Seaboard Service pattersonship@connect. Sanjay Prasad n Shipping Schedule - Patterson Brothers S Suva Patterson (Patterson Brothers Seaboard com.fj /a eaboard Shipping co Brothers Shipping Co Ltd) Suite 182, + 679 3315644 Seaboard Epwoth House, Nina Street, Shipping co. Suva, Fiji. +6799221335 Port of Goundar Lot 22, Freeston Road, Walu goundarshipping@kidane Tel: + 679 3301060 n Shipping Schedule - Goundar Shipping Suva Shipping co. Bay, Suva. t.com.fj /a co Mobile: +6797775471 (Rakesh) +679 7775462 (Krishna) Vanua Wharf off Amra Street, Walu http://www. -

Handbook for Teachers of Samoan Students in Western Schools. PUB DATE 1999-03-00 NOTE 81P.; Page Numbers in Table of Contents Are Incorrect

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 431 573 RC 022 011 AUTHOR Vaipae, Sharon Siebert TITLE Handbook for Teachers of Samoan Students in Western Schools. PUB DATE 1999-03-00 NOTE 81p.; Page numbers in table of contents are incorrect. Videotape not available from EDRS. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Classroom Communication; *Cultural Background; *Cultural Differences; Cultural Traits; Elementary Secondary Education; English (Second Language); *Intercultural Communication; *Samoan Americans; Second Language Learning; *Socialization IDENTIFIERS Samoa ABSTRACT This handbook provides classroom teachers with information to assist them in enhancing Samoan students' social adjustment and academic achievement in U.S. schools. The information complements the 25-minute videotape, Samoa, which is designed for student viewing. The handbook provides background information on the Samoan people, their islands, and Samoan schools and discusses reasons given by Samoans for migrating to Hawaii or the mainland. A chapter examines differences in culture between middle-class European Americans and traditional Samoans. Middle-class American family structure typically consists of a nuclear family with two children, while traditional Samoan families consist of an extended family structure with an average of seven children. A chapter on intercultural communication pragmatics describes principles of Samoan communication and provides context markers in Samoan communications such as eye gaze, posture, and gesture. A chapter focusing on linguistic considerations outlines differences encountered when using the Samoan language and lists problem sounds for Samoans in oral English. Contrasts in socialization between the two cultures are discussed. Using the framework suggested by Ogbu and Matute-Bianci, Samoans may be described as displaying primary differences of cultural content as well as secondary differences of cultural style. -

Page Auē Le Oti: Samoan Death Rituals in a New Zealand Context. Abstract

Auē le oti: Samoan death rituals in a New Zealand context. Byron Malaela Sotiata Seiuli1 University of Waikato Abstract Given that dialogue relating to death and grief for many Samoans still remains in the realm of tapu (sacred) or sā (protected), few attempts have been made by researchers of Samoan heritage to understand whether the cultural contexts for enacting associated rituals might also provide avenues for healing. Psychological scholarship on recovery following death, particularly among men, is largely based on dominant western perspectives that continue to privilege both clinical and ethnocentric perspectives as the norm. This case presentation, which forms part of a larger doctoral research by the author, demonstrates that some Samoan end-of-life rituals opens space for greater consideration of recovery from death as a culturally-defined process. In many instances, instead of severing ties with the deceased person as is popular in clinical approaches to grief work, Samoan grief resolution strongly endorses continued connections through its mourning patterns. Their end-of-life enactment helps to transition the deceased from this life to the next, while drawing the living together. Critically, the performance and maintenance of such important tasks create space for heaving emotions to be calmed, where meaning is made, and where the lives of those impacted are slowly restored. Some of these familiar rituals offer therapeutic value, enabling Samoans involved in this study to walk hand-in-hand with their emotional distress, while -

Indigenous Itaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr

Indigenous iTaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo Illustration by Cecelia Faumuina Author Dr Tarisi Vunidilo Tarisi is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, where she teaches courses on Indigenous museology and heritage management. Her current area of research is museology, repatriation and Indigenous knowledge and language revitalization. Tarisi Vunidilo is originally from Fiji. Her father, Navitalai Sorovi and mother, Mereseini Sorovi are both from the island of Kadavu, Southern Fiji. Tarisi was born and educated in Suva. Front image caption & credit Name: Drua Description: This is a model of a Fijian drua, a double hulled sailing canoe. The Fijian drua was the largest and finest ocean-going vessel which could range up to 100 feet in length. They were made by highly skilled hereditary canoe builders and other specialist’s makers for the woven sail, coconut fibre sennit rope and paddles. Credit: Commissioned and made by Alex Kennedy 2002, collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE011790. Link: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/648912 Page | 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: PREHISTORY OF FIJI .............................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3: ITAUKEI SOCIAL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... -

Priorities of the People: Hardship in the Fiji Islands

Priorities of the People HARDSHIP IN THE FIJI ISLANDS September 2003 Asian Development Bank © Asian Development Bank 2003 All rights reserved This publication was prepared by consultants for the Asian Development Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in it do not necessarily repre- sent the views of ADB or those of its member governments. ADB does not guar- antee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any consequences of their use. Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980 Manila, Philippines Website: www.adb.org Contents Introduction 1 Is Hardship Really a Problem in the Fiji Islands? 3 What is Hardship? 4 Who is Facing Hardship? 6 What Causes Hardship? 7 What Can be Done? 13 © Asian Development Bank 2003 All rights reserved This publication was prepared by consultants for the Asian Development Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in it do not necessarily repre- sent the views of ADB or those of its member governments. ADB does not guar- antee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any consequences of their use. Asian Development Bank P.O. Box 789, 0980 Manila, Philippines Website: www.adb.org Contents Introduction 1 Is Hardship Really a Problem in the Fiji Islands? 3 What is Hardship? 4 Who is Facing Hardship? 6 What Causes Hardship? 7 What Can be Done? 13 Introduction iji has commonly been viewed as a society with deep inequalities, but little absolute poverty. But many F people now believe that poverty—in the form of destitu- tion, homelessness, and hunger—exists in Fiji. -

The Metabolic Demands of Culturally-Specific

THE METABOLIC DEMANDS OF CULTURALLY-SPECIFIC POLYNESIAN DANCES by Wei Zhu A thesis submitted in partial FulFillment oF the requirements For the degree of Master oF Science in Health and Human Development MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana November 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Wei Zhu 2016 All Rights Reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 Historical Background ............................................................................................... 1 Statement oF Purpose ............................................................................................... 3 SigniFicance oF Study ................................................................................................. 3 Hypotheses ............................................................................................................... 4 Limitations ................................................................................................................ 5 Delimitations ............................................................................................................. 5 2. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ..................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 6 Health Status in NHOPI ............................................................................................. 6 PA – A Strategy -

Rotuman Identity in the Electronic Age

ALAN HOWARD and JAN RENSEL Rotuman identity in the Electronic Age For some groups cultural identity comes easy; at least it's relatively unprob- lematic. As Fredrik Barth (1969) pointed out many years ago, where bounda ries between groups are fixed and rigid, theories of group distinctiveness thrive. Boundaries can be set according to a wide range of physical, social, or cultural characteristics ranging from skin colour, religious affiliation or beliefs, occupations, to what people eat, and so on. Social hierarchy also can play a determining role, especially when a dominating group's social theory divides people into categories on the basis of geographical origins, blood lines, or some other defining characteristic, restricting their identity options. In the United States, for example, the historical category of 'negro' allowed little room for choice; any US citizen with an African ancestor was assigned to the category regardless of personal preference. Although in Polynesia social boundaries have traditionally been porous, cultural politics has transformed categories like 'New Zealand Maori' and 'Hawaiian' into strong identities, despite more personal choice and somewhat flexible boundaries. In these cases, where indigenous people were subjugated by European or American colonists, a long period of historically muted iden tity gave way in the last decades of the twentieth century to a Polynesian cul tural renaissance that has been accompanied by a hardening of social catego ries and a dramatic strengthening of Maori and Hawaiian identities. Samoans also have a relatively strong sense of cultural identity, but for a different reason. In their case, identity is reinforced by a commitment to fa'asamoa, the Samoan way of life. -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago