Rotuman Identity in the Electronic Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotuman Educational Resource

Fäeag Rotuam Rotuman Language Educational Resource THE LORD'S PRAYER Ro’ạit Ne ‘Os Gagaja, Jisu Karisto ‘Otomis Ö’fāat täe ‘e lạgi, ‘Ou asa la ȧf‘ȧk la ma’ma’, ‘Ou Pure'aga la leum, ‘Ou rere la sok, fak ma ‘e lạgi, la tape’ ma ‘e rȧn te’. ‘Äe la nāam se ‘ạmisa, ‘e terạnit 'e ‘i, ta ‘etemis tē la ‘ā la tạu mar ma ‘Äe la fạu‘ạkia te’ ne ‘otomis sara, la fak ma ne ‘ạmis tape’ ma rē vạhia se iris ne sar ‘e ‘ạmisag. ma ‘Äe se hoa’ ‘ạmis se faksara; ‘Äe la sại‘ạkia ‘ạmis ‘e raksa’a, ko pure'aga, ma ne’ne’i, ma kolori, mou ma ke se ‘äeag, se av se ‘es gata’ag ne tore ‘Emen Rotuman Language 2 Educational Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY 4 ROGROG NE ROTUMA 'E 'ON TẠŪSA – Our history 4 'ON FUẠG NE AS TA ROTUMA – Meaning behind Rotuma 5 HẠITOHIẠG NE FUẠG FAK PUER NE HANUA – Chiefly system 6 HATAG NE FĀMORI – Population 7 ROTU – Religion 8 AGA MA GARUE'E ROTUMA – Lifestyle on the island 8 MAK A’PUMUẠ’ẠKI(T) – A treasured song 9 FŪ’ÅK NE HANUA GEOGRAPHY 10 ROTUMA 'E JAJ(A) NE FITI – Rotuma on the map of Fiji 10 JAJ(A) NE ITU ’ HIFU – Map of the seven districts 11 FÄEAG ROTUẠM TA LANGUAGE 12 'OU ‘EA’EA NE FÄEGA – Pronunciation Guide 12-13 'ON JĪPEAR NE FÄEGA – Notes on Spelling 14 MAF NE PUKU – The Rotuman Alphabet 14 MAF NE FIKA – Numbers 15 FÄEAG ‘ES’ AO - Useful words 16-18 'OU FÄEAG’ÅK NE 'ÄE – Introductions 19 UT NE FAMORI A'MOU LA' SIN – Commonly Frequented Places 20 HUẠL NE FḀU TA – Months of the year 21 AG FAK ROTUMA CULTURE 22 KATO’ AGA - Traditional ceremonies 22-23 MAMASA - Welcome Visitors and returnees 24 GARUE NE SI'U - Artefacts 25 TĒFUI – Traditional garland 26-28 MAKA - Dance 29 TĒLA'Ā - Food 30 HANUJU - Storytelling 31-32 3 ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY Legend has it that Rotuma’s first inhabitants Consequently, the two religious groups originated from Samoa led by Raho, a chief, competed against each other in the efforts to followed by the arrival of Tongan settlers. -

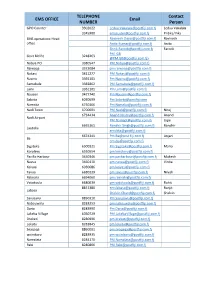

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Richard Feinberg, Ed., Seafaring in the Contemporary Pacific Islands: Studies in Continuity and Change

reviews Page 121 Monday, February 12, 2001 2:29 PM Reviews 121 Richard Feinberg, ed., Seafaring in the Contemporary Pacific Islands: Studies in Continuity and Change. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1995. Pp. 245, illus. US$35 cloth. Reviewed by Nicholas J. Goetzfridt, University of Guam There has been an interesting as well as a tired dichotomy of thinking about “voyaging” in the Pacific. Interesting because of questions concerned with the ability of voyagers to control their efforts across vast areas of a watery space in order to reach land and, in the settlement eras, to successfully prosper and possibly engage in return voyages of communication. These speculations, attempts at documentation through the paucity of European references to these voyagers, and the practical experiments undertaken by David Lewis and Ben Finney are all concerned with what must be seen as incredible journeys, regardless of how they were actually achieved. The thinking has been tired because of a habitual practice in all kinds of literature, both scholarly and popular, to assign an either/or identity to “voy- aging.” As we are occasionally told in comments usually tucked away in the bowels of some greater concern with modernity, this voyaging, for all its illus- trious past, is now “dead.” And as such, it wallows in the past. It is only the romantics, the individuals pricked by a yearning for the spectacular, who resist recognizing this foundational fact of Pacific life. Outboard motors and jet planes have nothing to do with this heritage. It is a loss basic to “contact” reviews Page 122 Monday, February 12, 2001 2:29 PM 122 Pacific Studies, Vol. -

Fiji Meteorological Service Government of Republic of Fiji

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICE GOVERNMENT OF REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No. 13 1pm, Wednesday, 16 December, 2020 SEVERE TC YASA INTENSIFIES FURTHER INTO A CATEGORY 5 SYSTEM AND SLOW MOVING TOWARDS FIJI Warnings A Tropical Cyclone Warning is now in force for Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands and expected to be in force for the rest of the group later today. A Tropical Cyclone Alert remains in force for the rest Fiji A Strong Wind Warning remains in force for the rest of Fiji. A Storm Surge and Damaging Heavy Swell Warning is now in force for coastal waters of Rotuma, Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands. A Heavy Rain Warning remains in force for the whole of Fiji. A Flash Flood Alert is now in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams along Komave to Navua Town, Navua Town to Rewa, Rewa to Korovou and Korovou to Rakiraki in Vanua Levu and is also in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams of Vanua Levu along Bua to Dreketi, Dreketi to Labasa and along Labasa to Udu Point. Situation Severe tropical cyclone Yasa has rapidly intensified and upgraded further into a category 5 system at 3am today. Severe TC Yasa was located near 14.6 south latitude and 174.1 east longitude or about 440km west-northwest of Yasawa-i-Rara, about 500km northwest of Nadi and about 395km southwest of Rotuma at midday today. The system is currently moving eastwards at about 6 knots or 11 kilometers per hour. -

Flood Hazard Modelling and Risk Assessment in the Nadi River Basin, Fiji, Using GIS and MCDA

CSIRO PUBLISHING The South Pacific Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences, 30, 33-43, 2012 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/spjnas 10.1071/SP12003 Flood hazard modelling and risk assessment in the Nadi River Basin, Fiji, using GIS and MCDA Jessy Paquette and John Lowry School of Geography, Earth Science and Environment, Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment, The University of the South Pacific, Private Mail Bag, Suva, Fiji. Abstract This paper presents a simple and affordable approach to flood hazard assessment in a region where primary data are scarce. Using a multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach coupled with GIS layers for elevation, catchments, land-use, slope, distance from channel, and soil types, we model the spatial extent of flood hazard in the Nadi River basin in western Fiji. Based on the flood hazard model results we assess risk to flood hazards in the greater Nadi area. This is carried out using 2007 census data and building location data obtained from aerial photography. The flood model reveals that the highest hazard areas in Nadi are the Narewa, Sikituru and Yavusania villages followed by the Nadi central business district (Nadi CBD). Closer examination of the data suggests that the Nadi River is not the only flood vector in the area. Several poorly designed storm drains also present a hazard since they get clogged by rubbish and cannot properly evacuate runoff thus creating water build-up. We conclude that the MCDA approach provides a simple and effective means to model flood hazard using basic GIS data. This type of model can help decision makers focus their flood risk awareness efforts, and gives important insights to disaster management authorities. -

Current and Future Climate of the Fiji Islands

Rotuma eef a R Se at re Ahau G p u ro G a w a Vanua Levu s Bligh Water Taveuni N a o Y r th er Koro n La u G ro Koro Sea up Nadi Viti Levu SUVA Ono-i-lau S ou th er n L Kadavu au Gr South Pacific Ocean oup Current and future climate of the Fiji Islands > Fiji Meteorological Service > Australian Bureau of Meteorology > Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Fiji’s current climate Across Fiji the annual average temperature is between 20-27°C. Changes Fiji’s climate is also influenced by the in the temperature from season to season are relatively small and strongly trade winds, which blow from the tied to changes in the surrounding ocean temperature. east or south-east. The trade winds bring moisture onshore causing heavy Around the coast, the average night- activity. It extends across the South showers in the mountain regions. time temperatures can be as low Pacific Ocean from the Solomon Fiji’s climate varies considerably as 18°C and the average maximum Islands to east of the Cook Islands from year to year due to the El Niño- day-time temperatures can be as with its southern edge usually lying Southern Oscillation. This is a natural high as 32°C. In the central parts near Fiji (Figure 2). climate pattern that occurs across of the main islands, average night- Rainfall across Fiji can be highly the tropical Pacific Ocean and affects time temperatures can be as low as variable. On Fiji’s two main islands, weather around the world. -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

FEMIS ECE Contact List- 2020

FEMIS ECE Contact List- 2020 School Code School Name District Telephone Email Location Mailing Address 8759 Abaca Early Learning Lautoka- Abaca PO Box 6729, Kindergarten Yasawa Village, Lautoka Lautoka 9762 Abc Kindergarten Nadroga- 4503979 [email protected] Tau Fijian P O Box 2164, Nadi, Navosa School Compound 8416 Adi Maopa Eastern 3545234 [email protected] Lomaloma P O Lomaloma Kindergarten Vanuabalavu 8138 Agape Kindergarten Lautoka- Lautoka Yasawa 9934 Aman's Memorial Suva 8725963 23 Borete P O Box 8118, Kindergarten Rd. , Valelevu, Nadawa, nasinu 8736 Amazing Grace Suva 8667295 [email protected] Lot 13 Stage P O Box 18337 Suva Kindergarten Sakoca II Sakoca Sub-division Tamavua 8190 American International Lautoka- 6724949 [email protected] Nadi Back P O Box 9857 Nadi christian School Yasawa Road Airport Fiji Kindergarten 9606 Amichandra Lautoka- 4502415 [email protected] Lautoka City C/- P O Box 562, Kindergarten Yasawa Lautoka, 9972 Anand Kindergarten Nadroga- 706555 Nalovo, Nadi P O Box 1853, Nadi, Navosa 9665 Andrews Kindergarten Lautoka- 6707679 [email protected] Nadi College P O Box 1050, Nadi, Yasawa Road 8422 ANGEL KEEPERS Suva 8036739/9278 MAKOI LOT 26 KIA STREET, KINDERGARTEN 657 MAKOI 9006 Arya Kanya Ba-Tavua 6674107 1051aryakanyapathshala@gmail. Yalalevu P O BOX 106 Ba Kindergarten com 9565 Arya Samaj Suva 3381194 / [email protected] 2. 5 Miles, P O Box 3877, Kindergarten Suva 2011497 / Samabula Samabula, 9220014 9776 Arya Samaj Natabua Lautoka- 6660127 [email protected] Natabua P O Box 1035, Ktn Yasawa Housing Lautoka, Settlement 9826 Avea Kindergarten Eastern 7458 162 [email protected] Avea Island, C/- Avea Primary Vanuabalav School, P O u, Lau Lomaloma, Vanuabalavu 9767 Ba Andhra Ba-Tavua 4501144 [email protected] Ba P O Box 429, Ba, Kindergarten 9018 Ba Muslim Ba-Tavua 6674485 [email protected] Yalalevu, Ba. -

Indigenous Itaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr

Indigenous iTaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo Illustration by Cecelia Faumuina Author Dr Tarisi Vunidilo Tarisi is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, where she teaches courses on Indigenous museology and heritage management. Her current area of research is museology, repatriation and Indigenous knowledge and language revitalization. Tarisi Vunidilo is originally from Fiji. Her father, Navitalai Sorovi and mother, Mereseini Sorovi are both from the island of Kadavu, Southern Fiji. Tarisi was born and educated in Suva. Front image caption & credit Name: Drua Description: This is a model of a Fijian drua, a double hulled sailing canoe. The Fijian drua was the largest and finest ocean-going vessel which could range up to 100 feet in length. They were made by highly skilled hereditary canoe builders and other specialist’s makers for the woven sail, coconut fibre sennit rope and paddles. Credit: Commissioned and made by Alex Kennedy 2002, collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE011790. Link: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/648912 Page | 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: PREHISTORY OF FIJI .............................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3: ITAUKEI SOCIAL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... -

Identified Gaps & Proposed Solutions & Logistics Planning

FIJI LOGISTICS PLANNING OVERVIEW Identified Gaps & proposed Solutions & Logistics Planning GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP PROGRAM FUNDED BY: 1 | P a g e A. LOGISTICS PLANNING OVERVIEW a. IDENTIFIED GAPS & PROPOSED SOLUTIONS Organizing emergency logistics operations for delivery and distribution may be a real challenge in Fiji due to the remoteness of outer Islands, access conditions to affected locations on the main Islands and operational constraints in entry ports facilties. All actors agree that logistics is one of the major bottlenecks in past emergency responses. On the whole, both logistics infrastructures and services are in place in Fiji. Technical agencies in charge of those infrastructures and services are dedicated and competent. Emergency Logistics operations are generally organized, efficient and adequate. Nevertheless, some areas of improvement have been identified. These areas are detailed here under together with propositions to address those gaps. A separate “Logistics Preparedness Plan” has been drafted to implement those propositions of improvement. LOGISTICS RELATED GAPS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: The logistics gaps identified concern the following subjects: o Coordination & Preparedness o Networking o Human Resources o Capitalization o Information Management o Storage o Commodities tracking o Operational and access challenges Coordination & Preparedness Cyclones / Floods seasons need to be prepared, also regarding logistics issues. The logistics coordination needs to meet before the wet season to prepare for potential emergencies, revise everybody’s roles and responsibilities, etc. Stand-by agreements / protocols could be established and agreed upon prior to emergencies with key emergency actors, including customs, RFMF, Police, private companies, etc. Formalize transport options ahead of the cyclone season. Sectors concerned are: customs, transport (land, sea, and air), and storage, dispatching and tracking. -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Rotuma Wide Governments to Deal with the New Threats 14 May That Government Was Overthrown in a Mili Failed

Rotuma wide governments to deal with the new threats 14 May that government was overthrown in a mili failed. Facing the prospect of continuing instability tary coup led by Sitiveni Rabuka (FIJI COUPS). Fol and insistent demands by outsiders, Cakobau and lowing months of turmoil and delicate negotiations, other leading chiefs of Fiji ceded Fiji to Great Britain Fiji was returned to civilian rule in December 1987. on 10 October 1874 (DEED OF CESSION). A new constitution, entrenching indigenous domi Sir Arthur GORDON was appointed the first sub nance in the political system, was decreed in 1990, stantive governor of the new colony. His policies which brought the chiefs-backed Fijian party to and vision laid the foundations of modern Fiji. He political power in 1992. forbade the sale of Fijian land and introduced an The constitution, contested by non-Fijians for its 'indirect system' of native administration that racially-discriminatory provisions, was reviewed by involved Fijians in the management of their own an independent commission in 1996 (CONSTITUT affairs. A chiefly council was revived to advise the ION REVIEW IN FIJI), which recommended a more government on Fijian matters. To promote economic open and democratic system encouraging the forma development, he turned to the plantation system he tion of multi-ethnic governments. A new constitu had seen at first hand as governor of Trinidad and tion, based on the commission's recommendations, Mauritius. The Australian COLONIAL SUGAR was promulgated a year later, providing for the rec REFINING COMPANY was invited to extend its ognition of special Fijian interests as well as a consti operation to Fiji, which it did in 1882, remaining in tutionally-mandated multi-party cabinet.