Kennedy-Wunsch Lecture 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Chadwick: Ahead of His Time

July 15, 2020 James Chadwick: ahead of his time Gerhard Ecker University of Vienna, Faculty of Physics Boltzmanngasse 5, A-1090 Wien, Austria Abstract James Chadwick is known for his discovery of the neutron. Many of his earlier findings and ideas in the context of weak and strong nuclear forces are much less known. This biographical sketch attempts to highlight the achievements of a scientist who paved the way for contemporary subatomic physics. arXiv:2007.06926v1 [physics.hist-ph] 14 Jul 2020 1 Early years James Chadwick was born on Oct. 20, 1891 in Bollington, Cheshire in the northwest of England, as the eldest son of John Joseph Chadwick and his wife Anne Mary. His father was a cotton spinner while his mother worked as a domestic servant. In 1895 the parents left Bollington to seek a better life in Manchester. James was left behind in the care of his grandparents, a parallel with his famous predecessor Isaac Newton who also grew up with his grandmother. It might be an interesting topic for sociologists of science to find out whether there is a correlation between children educated by their grandmothers and future scientific geniuses. James attended Bollington Cross School. He was very attached to his grandmother, much less to his parents. Nevertheless, he joined his parents in Manchester around 1902 but found it difficult to adjust to the new environment. The family felt they could not afford to send James to Manchester Grammar School although he had been offered a scholarship. Instead, he attended the less prestigious Central Grammar School where the teaching was actually very good, as Chadwick later emphasised. -

Ernest Rutherford and the Accelerator: “A Million Volts in a Soapbox”

Ernest Rutherford and the Accelerator: “A Million Volts in a Soapbox” AAPT 2011 Winter Meeting Jacksonville, FL January 10, 2011 H. Frederick Dylla American Institute of Physics Steven T. Corneliussen Jefferson Lab Outline • Rutherford's call for inventing accelerators ("million volts in a soap box") • Newton, Franklin and Jefferson: Notable prefiguring of Rutherford's call • Rutherfords's discovery: The atomic nucleus and a new experimental method (scattering) • A century of particle accelerators AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 Rutherford’s call for inventing accelerators 1911 – Rutherford discovered the atom’s nucleus • Revolutionized study of the submicroscopic realm • Established method of making inferences from particle scattering 1927 – Anniversary Address of the President of the Royal Society • Expressed a long-standing “ambition to have available for study a copious supply of atoms and electrons which have an individual energy far transcending that of the alpha and beta particles” available from natural sources so as to “open up an extraordinarily interesting field of investigation.” AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 Rutherford’s wish: “A million volts in a soapbox” Spurred the invention of the particle accelerator, leading to: • Rich fundamental understanding of matter • Rich understanding of astrophysical phenomena • Extraordinary range of particle-accelerator technologies and applications AAPT Winter Meeting January 10, 2011 From Newton, Jefferson & Franklin to Rutherford’s call for inventing accelerators Isaac Newton, 1717, foreseeing something like quarks and the nuclear strong force: “There are agents in Nature able to make the particles of bodies stick together by very strong attractions. And it is the business of Experimental Philosophy to find them out. -

NEWSLETTER Issue No. 3 February 2011

NEWSLETTER February 2011 Issue no. 3 Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment by Kara Page See http://np.iop.org for further details Nuclear Physics Group newsletter Feb 2011 Conferences in 2011 The group would particularly like to attract your attention to two major forthcoming conferences that will take place in the UK this year. This year, the IOP Nuclear Physics group will join with 4 other IOP subject groups, High Energy Particle Physics, Gravitational Physics, Astroparticle Physics and Particle Accelerators and Beams Groups, for its annual conference. The five groups will meet together for four days at the University of Glasgow from the 4th of April 2011. This conference will be one of the largest, most exciting and broadest ranged NPP divisional conference ever held. Further information can be found at: http://www.iop.org/events/scientific/conferences/index.html . From the 8th to 12th of August 2011, an international conference celebrating the 100th anniversary of Rutherford’s publication on the atomic nucleus discovery will take place at the University of Manchester. For more information, please visit the web site: http://rutherford.iop.org/. The Geiger–Marsden experiment (also called the Gold foil) was an experiment to probe the structure of the atom performed by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden in 1909, under the direction of Ernest Rutherford at the Physical Laboratories of the University of Manchester. The unexpected results of the experiment demonstrated for the first time the existence of the atomic nucleus, leading to the downfall of the plum pudding model of the atom, and the development of the Rutherford (or planetary) model. -

Some Personal Overviews by Hugh Jamieson Bruce White Ray Trott

b The development of MEDICAL PHYSICS and BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING in NEW ZEALAND HOSPITALS 1945-1995 _____________ Some personal overviews by Hugh Jamieson Bruce White Ray Trott Jack Tait Gordon Monks __________ Editor H D Jamieson ___________ Second edition First published 1995 Second edition 1996 Reprinted 2006 ISBN 0-476-01437-9 ii CONTENTS Second edition Index of photographs; Staff lists .. .. .. .. iv Preface, and Preface to Second Edition .. .. .. 1 Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Early hospital physics in NZ: "Some memory fragments" 3 Around the centres (first appointments in the 6 centres) 7 Supervoltage radiotherapy (summary) .. .. .. 8 Nuclear medicine (summary) .. .. .. .. .. 12 Nuclear medicine imaging (summary) .. .. .. 14 Biomedical engineering (summary) .. .. .. .. 15 Computing in hospitals (summary) .. .. .. .. 18 The ongoing developments (summary); Conclusion .. 20 Photograph, 1954 inaugural NZMPA meeting, Christchurch 21 Hospital/Medical Physics in Dunedin - Hugh Jamieson 23 Wellington Hospital - Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering .. 62 Hospital Physics Beginnings at Auckland Hospital .. 68 The History of Nuclear Medicine in Auckland -Bruce White 71 Auckland Hospital...Medical Physics & Clinical Engineering - Bruce White 83 Hospital/Medical Physics at Palmerston North Hospital - Ray Trott 97 Medical Physics & Bioengineering at Christchurch Hospital - Jack Tait 108 Hospital Physics / Scientific Services at Waikato Hospital - Gordon Monks 135 Retrospect and contemplation .. .. .. .. 151 = = = = = = = = = = = -

Portraits from Our Past

M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 1 15/07/2016 10:32 Medics, Mechanics and Manchester Charting the history of the University Joseph Jordan’s Pine Street Marsden Street Manchester Mechanics’ School of Anatomy Medical School Medical School Institution (1814) (1824) (1829) (1824) Royal School of Chatham Street Owens Medicine and Surgery Medical School College (1836) (1850) (1851) Victoria University (1880) Victoria University of Manchester Technical School Manchester (1883) (1903) Manchester Municipal College of Technology (1918) Manchester College of Science and Technology (1956) University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (1966) e University of Manchester (2004) M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 2 15/07/2016 10:32 Contents Roots of the University 2 The University of Manchester coat of arms 8 Historic buildings of the University 10 Manchester pioneers 24 Nobel laureates 30 About University History and Heritage 34 History and heritage map 36 The city of Manchester helped shape the modern world. For over two centuries, industry, business and science have been central to its development. The University of Manchester, from its origins in workers’ education, medical schools and Owens College, has been a major part of that history. he University was the first and most Original plans for eminent of the civic universities, the Christie Library T furthering the frontiers of knowledge but included a bridge also contributing to the well-being of its region. linking it to the The many Nobel Prize winners in the sciences and John Owens Building. economics who have worked or studied here are complemented by outstanding achievements in the arts, social sciences, medicine, engineering, computing and radio astronomy. -

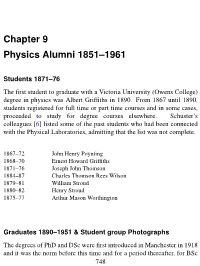

Chapter 9 Physics Alumni 1851–1961

Chapter 9 Physics Alumni 1851–1961 Students 1871–76 The first student to graduate with a Victoria University (Owens College) degree in physics was Albert Griffiths in 1890. From 1867 until 1890, students registered for full time or part time courses and in some cases, proceeded to study for degree courses elsewhere. Schuster’s colleagues [6] listed some of the past students who had been connected with the Physical Laboratories, admitting that the list was not complete. 1867–72 John Henry Poynting 1868–70 Ernest Howard Griffiths 1871–76 Joseph John Thomson 1884–87 Charles Thomson Rees Wilson 1879–81 William Stroud 1880–82 Henry Stroud 1875–77 Arthur Mason Worthington Graduates 1890–1951 & Student group Photographs The degrees of PhD and DSc were first introduced in Manchester in 1918 and it was the norm before this time and for a period thereafter, for BSc 748 graduates to follow up with a one year MSc course. 1890 First Class: Albert Griffiths. Third Class: Ernest Edward Dentith Davies. Albert Griffiths Assoc. Owens 1890, MSc 1893, DSc 1899. After graduating, Albert Griffiths was a research student, fellow, demonstrator and lecturer at Owens between 1892 and 1898, in between posts at Freiburg, Southampton and Sheffield. He became Head of the Physics Department at Birkbeck in 1900. E E D Davies, born on the Isle of Man, obtained a BSc in mathematics in 1889, an MSc in 1892, a BA in 1893 before becoming a Congregational Minister in 1895. Joseph Thompson lists him [246], as a student at the Lancashire Independent College in 1893. -

Ernest Marsden's Nuclear New Zealand

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 139, p. 23–38, 2006 ISSN 0035-9173/06/010023–16 $4.00/1 Ernest Marsden’s Nuclear New Zealand: from Nuclear Reactors to Nuclear Disarmament rebecca priestley Abstract: Ernest Marsden was secretary of New Zealand’s Department of Scientific and Industrial Research from 1926 to 1947 and the Department’s scientific adviser in London from 1947 to 1954. Inspired by his early career in nuclear physics, Marsden had a post-war vision for a nuclear New Zealand, where scientists would create radioisotopes and conduct research on a local nuclear reactor, and industry would provide heavy water and uranium for use in the British nuclear energy and weapons programmes, with all these ventures powered by energy from nuclear power stations. During his retirement, however, Marsden conducted research into environmental radioactivity and the impact of radioactive bomb fallout and began to oppose the continued development and testing of nuclear weapons. It is ironic, given his early enthusiasm for all aspects of nuclear development, that through his later work and influence Marsden may have actually contributed to what we now call a ‘nuclear-free’ New Zealand. Keywords: Ernest Marsden, heavy water, nuclear, New Zealand INTRODUCTION to nuclear weapons development – which he was happy to support in the 1940s and 1950s In the 1990s, Ross Galbreath established Ernest – changed in his later years. By necessity this Marsden as having been the driving force be- article includes some material already covered hind the involvement of New Zealand scientists by Galbreath and Crawford but it also covers on the Manhattan and Montreal projects, the new ground. -

Moseley and Atomic Numbers

Rediscovery of the Elements Moseley and Atomic Numbers ing the Industrial Revolution which brought wealth and prosperity to the community. By the mid-1800s, Manchester was the second largest III city in England and gained a reputation as a center of invention and technological progress. In 1781 a prestigious scientific institution was founded— the Literary and Philosophical Society (commonly known as the “Lit. and Phil.”).1 In this society John Dalton (1766–1844),2a who arrived in Manchester in 1793, formulated his atomic theory at the turn of the century.3 At the very same platform4 where Dalton proposed his idea of atoms and James L. Marshall, Beta Eta 1971, and atomic masses (Figures 1, 2), Ernest Rutherford Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003, one century later first proposed the nuclear Department of Chemistry, University of atom, a dense positive core surrounded by elec- 5 North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, trons. Ernest Rutherford had arrived in 1907 from [email protected] McGill University, Montreal, Canada.2d At the University of Manchester (then named the Introduction. Manchester in northwest Victoria University of Manchester) he assem- England was founded as a Roman fort in 79 bled a powerful team of gifted individuals Figure 1. This was the Literary and Philosophical A.D. After the Roman departure it evolved into including an Oxford graduate named Henry building at 36 George Street in Manchester built in a typical Medieval village and after a millenni- Gwyn-Jeffreys Moseley (1887–1915), who 1799 which served the scientific community for 140 um matured into a manufacturing giant. -

Hans Geiger E Ernest Marsden Em Manchester (1909-1910): 100 Anos Dos “Experimentos De Rutherford” Com Partículas Α

Sociedade Brasileira de Química ( SBQ) Hans Geiger e Ernest Marsden em Manchester (1909-1910): 100 anos dos “experimentos de Rutherford” com partículas α. Cesar Valmor Machado Lopes 1* (PQ), Roberto de Andrade Martins 2 (PQ). 1Departamento de Ensino e Currículo, Faculdade de Educação, UFRGS. Grupo Interdisciplinar em Filosofia e História da Ciência, Instituto Latino Americano de Estudos Avançados, UFRGS. *[email protected]. 2Grupo de História e Teoria da Ciência, Departamento de Raios Cósmicos e Cronologia, Instituto de Física “Gleb Wataghin”, UNICAMP. Palavras Chave: Hans Geiger; Ernest Marsden; partículas alfa; modelos atômicos; história do átomo. Geiger em 1 fevereiro de 1910 (lida em 17 de O Contexto fevereiro) 2. No artigo publicado em 1910, Geiger além de No final da primeira década do século XX, o apresentar os resultados obtidos, fez uma descrição jovem Dr. Hans Geiger (1882-1945) e o estudante mais detalhada dos experimentos e destacou o ouro de graduação Ernest Marsden (1889-1970) atuavam dentre os metais testados. Os resultados obtidos no Laboratório dirigido por Ernest Rutherford (1871- com lâminas de ouro acabariam tendo um lugar de 1937) em Manchester e procuravam desenvolver destaque no artigo publicado em seguida por novos métodos de contagem de partículas alfa nos Rutherford e na história que se conta sobre o dito fenômenos radioativos investigados e também “experimento de espalhamento de partículas alfa de explicar os resultados (in-penetrabilidade, in- Rutherford” que o teria levado a propor seu modelo permeabilidade, espalhamento) obtidos quando atômico. diferentes tipos de materiais eram bombardeados com essas radiações. Essas investigações levaram Considerações Rutherford a propor seu modelo de átomo nuclear em 1911, e ficaram conhecidas como “experimentos Após a publicação dos detalhados artigos de de Rutherford”. -

New Zealand Responses to the Peaceful Atom in the 1950S

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 139, p. 51–62, 2006 ISSN 0035-9173/06/010051–12 $4.00/1 Prospects for Enrichment: New Zealand Responses to the Peaceful Atom in the 1950s matthew o’meagher Abstract: The origin of the anti-nuclear movement in New Zealand is discussed. An assess- ment is made of the impact of the New Zealand Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament on New Zealand politics and foreign policy. Keywords: Anti-nuclear movement, New Zealand, New Zealand Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, politics, foreign policy, ‘Atoms for Peace’. INTRODUCTION ful atom’ was the only or even the main fac- tor preventing New Zealand embracing the anti- This paper forms part of a wider study of the nuclear cause until the 1970s and 1980s; anti- history of anti-nuclear New Zealand before it be- communism, anti-Japanese sentiment, faith in came famous, its roots if you will, on which the and friendship towards the two original West- transformations in that nation’s identity and ern nuclear powers, and a host of factors spe- foreign policy of the 1970s and 1980s would cific to the arms race itself were more impor- grow. The heart of that project is the story tant. Nevertheless, Eisenhower’s initiative, in of a peace group I first researched as a student tandem with a coincidental burst of hope that two decades ago, the New Zealand Campaign this country might have uranium deposits of its for Nuclear Disarmament (NZCND). This coun- own to exploit, did revive official and popular try’s first exclusively anti-nuclear national or- interest in the peaceful uses of atomic energy, ganisation, it tried to convert New Zealanders to just as it did elsewhere in the world, thereby the disarmament cause in the early 1960s, and diverting New Zealanders’ attention away from was a local manifestation of the second stage of more disturbing nuclear developments. -

The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time / Edited by Kara Rogers.—1St Ed

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2010 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition Kara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical Sciences Rosen Educational Services Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Introduction by Kristi Lew Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The 100 most influential scientists of all time / edited by Kara Rogers.—1st ed. p. cm.—(The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-040-2 (eBook) 1. Science—Popular works. 2. Science—History—Popular works. 3. Scientists— Biography—Popular works. I. Rogers, Kara. -

Rutherford and the Nuclear Atom

I NTERNATIONAL J OURNAL OF H IGH -E NERGY P HYSICS CERNCOURIER V OLUME 5 1 N UMBER 4 M AY 2 0 1 1 Rutherford and the nuclear atom QED TECHNOLOGY PHYSICS IN Studying strong Unravelling a story fi elds in crystal of sparkling THE ALPS targets spin-off News from the Rencontres p15 p18 de Moriond 2011 p25 CCMay11-Cover.indd 1 12/04/2011 18:01 Instrumentation Technologies Libera Hadron Hadron beam position processor High-resolution measurements for circular You also benefit from: • Large playground for custom-written applications: hadron machines. Virtex™ 5, COM Express Basic module Basic features: • More space: up to 16 input channels to simultaneously • High-resolution single bunch position measurements acquire the position from 8 BPM planes in one chassis • Single bunch precise charge measurements • Two year hardware warranty with the option for an • Turn-by-turn, high resolution beam position and charge extension measurements • Slow acquisition streaming beam position measurements Typical Performance Advanced features: • High resolution single bunch arrival time measurements Single bunch resolution Turn-by-turn resolution • Fast acquisition: very high resolution beam position below 5 um RMS (2 Vp-p, below 1 um RMS (2 Vp-p, 80 kHz measurements and 10 kHz rate streaming on a dedicated 106 ns repetition rate) revolution frequency) output for fast feedback purposes • Bunch map and bunch fill pattern measurements • Implementation of low-latency multi-bunch instability Combine Libera Hadron with Libera Single Pass H and feedback systems Libera LLRF and further improve beam stability! Request the Promo unit and purchase your first Libera Hadron at a discounted price, including the money-back warranty option at [email protected]! www.i-tech.si Many instruments.