Goapuri & Goa Velha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

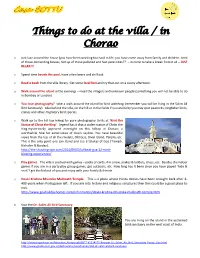

Things to Do at the Villa / in Chorao

Things to do at the villa / in Chorao o Just laze around the house (you have been working too hard in life, you have come away from family and children, tired of those demanding bosses, fed up of those polluted and fast pace cities?? – its time to take a break from it all – JUST RELAX!!!. o Spend time beside the pool, have a few beers and chill out. o Read a book from the villa library. Get some local feni and try that out on a sunny afternoon. o Walk around the island in the evenings – meet the villagers and unknown people (something you will not be able to do in Bombay or London). o You love photography? take a walk around the island for bird watching (remember you will be living in the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary). Also behind the villa, on the hill or in the fields if you are lucky you may spot peacocks, kingfisher birds, cranes and other migratory bird species. o Walk up to the hill top hiking for pure photography thrills at ‘Krist Rei Statue of Christ the King’. Legend has it that a stolen statue of Christ the King mysteriously appeared overnight on this hilltop in Chorao; a worthwhile hike for aerial views of Goa’s skyline. You have beautiful views from the top of all the rivulets, Old Goa, Divar Island, Panjim, etc. This is the only point one can stand and see 3 talukas of Goa (Tiswadi, Bicholim & Bardez). http://the-shooting-star.com/2014/09/02/offbeat-goa-12-mind- blowing-experiences/ o Play games. -

Audit-Reg-Corp.Pdf

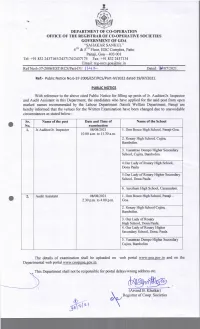

Venues for the post of Jr. Auditor/Jr. Inspector Date and Day: Sunday 08.08.2021 Time:10.00 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. Morning Session Sr. Name of the School Roll No. No. 1. Don Bosco High School, Panaji – Goa 1 to 500 2. Rosary High School, Cujira, Bambolim 501 to 940 3. Vasantrao Dempo Higher Secondary 941 to 1063 School, Cujira, Bambolim 4. Our Lady of Rosary High School, 1064 to 1339 Dona Paula 5. Our Lady of Rosary Higher Secondary 1340 to 1539 School, Dona Paula 6. Auxilium High School, Caranzalem 1540 to 1639 Venues for the post of Audit Assistant Date and Day: Sunday 08.08.2021 Time: 2.30 p.m. to 4.00 p.m. Evening Session Sr. Name of the School Roll No. No. 1. Don Bosco High School, Panaji – Goa 1 to 500 2. Rosary High School, Cujira, Bambolim 501 to 940 3. Our Lady of Rosary High School, 941 to 1240 Dona Paula 4. Our Lady of Rosary Higher Secondary 1241 to 1440 School, Dona Paula 5. Vasantrao Dempo Higher Secondary 1441 to 1546 School, Cujira, Bambolim 1 List of the Candidates for the post of Audit Assistant for examination to be held on 08/08/2021 at 2.30 p.m. to 4.00 p.m. In Don Bosco High School, Panaji-Goa from Roll No. 001 to 500 Roll No. Name & Address of the Candidate 001 Muriel Philip D’ Souza, H. No. 156, Angod, Mapusa, Bardez Goa. 002 Nivedita Sudhakar Achari, H. No. 271, khareband Road, Margao Goa 403601. -

International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage

Abstract Volume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Abstract Volume: Intenational Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage 21th - 23rd August 2013 Sri Lanka Foundation, Colombo, Sri Lanka Editor Anura Manatunga Editorial Board Nilanthi Bandara Melathi Saldin Kaushalya Gunasena Mahishi Ranaweera Nadeeka Rathnabahu iii International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Copyright © 2013 by Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. First Print 2013 Abstract voiume: International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage Publisher International Association for Asian Heritage Centre for Asian Studies University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-4563-10-0 Cover Designing Sahan Hewa Gamage Cover Image Dwarf figure on a step of a ruined building in the jungle near PabaluVehera at Polonnaruva Printer Kelani Printers The views expressed in the abstracts are exclusively those of the respective authors. iv International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 In Collaboration with The Ministry of National Heritage Central Cultural Fund Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology Bio-diversity Secratariat, Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy v International Conference of the International Association for Asian Heritage 2011 Message from the Minister of Cultural and Arts It is with great pleasure that I write this congratulatory message to the Abstract Volume of the International Conference on Asian Art, Culture and Heritage, collaboratively organized by the Centre for Asian Studies, University of Kelaniya, Ministry of Culture and the Arts and the International Association for Asian Heritage (IAAH). It is also with great pride that I join this occasion as I am associated with two of the collaborative bodies; as the founder president of the IAAH, and the Minister of Culture and the Arts. -

Call Letter for the Post of Sweeper

BY REGISTERED A/D HIGH COURT OF BOMBAY AT GOA, PANAJI REF. ADVERTISMENT NO. 1/2016 No. HCB/GOA/A-1/Sweeper/2017/ Date : 04.10.2017 Latest Passport size Photograph of Entry No. : the candidate CALL LETTER With reference to your application for the post of Sweeper, you are required to appear for the Practical Test/Physical Fitness test/Viva-voce at the High Court of Bombay at Goa, Panaji, on 11.10.2017 from 11:00 a.m. onwards. The Practical test will be of 30 marks, Physical fitness (10 marks) and Viva Voce (10 marks). If you fail in Practical test you will not be considered for Physical fitness and for viva-voce for the post of Sweeper. Please note that you will have to appear for the Practical test/Physical fitness and Viva-voce at your own cost. You are required to bring this call letter with you on the day of Practical test/Physical fitness/Viva Voce along with all your testimonials in original. If you fail to bring this Call letter with you on the day of Practical test/Physical fitness/Viva Voce, perhaps you will not be allowed to appear for the same on 11.10.2017 as the case may be and no further opportunity shall be given. Any attempt on your part to influence or pressurise the members of the Selection Committee shall render you debarred from the selection process. (S. C. Chandak) Registrar (Adm.) To, Sr. Entry Name/Address of the candidates No. No. 1 25 VIKAS TULSHIDAS NAIK H. -

Easter 28 and 29Th, April

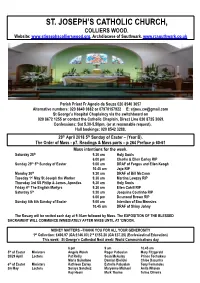

: ST. JOSEPH’S CATHOLIC CHURCH, COLLIERS WOOD. Website: www.stjosephscollierswood.org. Archdiocese of Southwark. www.rcsouthwark.co.uk ! Parish Priest Fr Agnelo de Souza 020 8540 3057 Alternative numbers: 020 8640 0882 or 07970157922 E: [email protected] St George’s Hospital Chaplaincy via the switchboard on 020 8672 1255 or contact the Catholic Chaplain, Direct Line 020 8725 3069. Confessions: Sat 5.30-5.50pm. (or at reasonable request). Hall bookings: 020 8542 3288. 29th April 2018 5th Sunday of Easter – (Year B). The Order of Mass - p7. Readings & Mass parts – p 264 Preface p 60-61 Mass intentions for the week. Saturday 28th 9.30 am Holy Souls 6.00 pm Charlie & Ellen Earley RIP Sunday 29th 5th Sunday of Easter 9.00 am DRAF of Fergus and Ellen Keogh 10.45 am Jojo RIP Monday 30th 9.30 am DRAF of Bill McCann Tuesday 1st May St Joseph the Worker 9.30 am Martina Lewzey RIP Thursday 3rd SS Philip & James, Apostles 9,30 am Holy Souls Friday 4th The English Martyrs 9.30 am Ellen Cahill RIP Saturday 5th 9.30 am Joaquina Coutinho RIP 6.00 pm Desmond Brown RIP Sunday 6th 6th Sunday of Easter 9.00 am Intention of Ena Menezes 10.45 am DRAF of Shiny Johny The Rosary will be recited each day at 9.10am followed by Mass. The EXPOSITION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT WILL COMMENCE IMMEDIATELY AFTER MASS UNTIL AT 12NOON. MONEY MATTERS –THANK YOU FOR ALL YOUR GENEROSITY 1st Collection: £400.97 (GA £146.00) 2nd £153.20 (GA £37.25) (Ecclesiastical Education) This week: St George’s Cathedral Next week: World Communications day 6 pm 9 am 10.45 am 5th of Easter Ministers Angela Walsh Roger Pabualan Mary Fitzgerald 28/29 April Lectors Pat Reilly Sean McAuley Prince Tochukwu Maria Guindano Damian Bielicki Chloe Dacunha 6th of Easter Ministers Kathleen Earley Estrella Pabualan Tony Fernandes 5/6 May Lectors Soraya Sanchez Maryanne Michael Anita Whelan Ray Hearn Mark Thorne Telma Oliveira : THE POWER OF AMEN. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

List of Recognised Educational Institutions in Goa 2010

GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in C O N T E N T Sr. No. Page No. 1. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Non- Professional] … … … 1 2. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Professional] … … … … 5 3. Institutions for Professional/Technical Education in Goa [Post Matric Level] … … … 8 4. Institutions for Professional/Technical/Other Education in Goa [School Level]… … … 13 5. Higher Secondary Schools: Government and Government Aided & Unaided … … … 14 6. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … 22 7. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … 31 8. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 37 9. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 38 10. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 39 11. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 48 12. Government High Schools (Central and State) … … … … … … … … 56 13. Government Middle Schools [North & South Goa Districts] … … … … … … 60 14. Government Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … … … 63 15. Government Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … … … 87 16. Special Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … … 103 17. National Open Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … 104 AFFILIATED COLLEGES AND RECOGNISED INSTITUTIONS IN GOA [NON – PROFESSIONAL] Sr. -

Ecological Status Assessment of Dr. Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary and Estuarine Areas of Chorao Island CMPA Technical Report Series No

1 Ecological Status Assessment of Dr. Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary and Estuarine Areas of Chorao Island CMPA Technical Report Series No. 09 Ecological Status Assessment of Dr. Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary and Estuarine Areas of Chorao Island Authors Dr. Fraddry D’Souza, Asha Giriyan, Dr. Chetan Gaonkar Kavita Patil, Santosh Gad Published by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Indo-German Biodiversity Programme (IGBP), GIZ-India, A-2/18, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi - 110029, India E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.giz.de July 2015 Responsible Dr. Konrad Uebelhör, Director, GIZ Cover Photo Thorsten Hiepko, GIZ Design and Layout Commons Collective, Bangalore [email protected] Disclaimer The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC), Government of India, nor the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) or the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. The designation of geographical entities and presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression or opinion whatsoever on the part of MoEFCC, BMUB, or GIZ concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Reference herein to any specific organization, consulting firm, service provider or process followed does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation or favouring by MoEFCC, BMUB or GIZ. Citation Dr. D’Souza Fraddry, A. -

The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010

– 1 – GOVERNMENT OF GOA The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010 – 2 – Edition: January 2017 Government of Goa Price Rs. 200.00 Published by the Finance Department, Finance (Debt) Management Division Secretariat, Porvorim. Printed by the Govt. Ptg. Press, Government of Goa, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Panaji-Goa – 403 001. Email : [email protected] Tel. No. : 91832 2426491 Fax : 91832 2436837 – 1 – Department of Town & Country Planning _____ Notification 21/1/TCP/10/Pt File/3256 Whereas the draft Regulations proposed to be made under sub-section (1) and (2) of section 4 of the Goa (Regulation of Land Development and Building Construction) Act, 2008 (Goa Act 6 of 2008) hereinafter referred to as “the said Act”, were pre-published as required by section 5 of the said Act, in the Official Gazette Series I, No. 20 dated 14-8- 2008 vide Notification No. 21/1/TCP/08/Pt. File/3015 dated 8-8-2008, inviting objections and suggestions from the public on the said draft Regulations, before the expiry of a period of 30 days from the date of publication of the said Notification in the said Act, so that the same could be taken into consideration at the time of finalization of the draft Regulations; And Whereas the Government appointed a Steering Committee as required by sub-section (1) of section 6 of the said Act; vide Notification No. 21/08/TCP/SC/3841 dated 15-10-2008, published in the Official Gazette, Series II No. 30 dated 23-10-2008; And Whereas the Steering Committee appointed a Sub-Committee as required by sub-section (2) of section 6 of the said Act on 14-10-2009; And Whereas vide Notification No. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

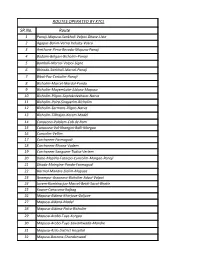

SR.No. Route ROUTES OPERATED by KTCL

ROUTES OPERATED BY KTCL SR.No. Route 1 Panaji-Mapusa-Sankhali-Valpoi-Dhave-Uste 2 Agapur-Borim-Verna Industy-Vasco 3 Amthane-Pirna-Revoda-Mapusa-Panaji 4 Badami-Belgavi-Bicholim-Panaji 5 Bamboli-Marcel-Valpoi-Signe 6 Bhiroda-Sankhali-Marcel-Panaji 7 Bibal-Paz-Cortalim-Panaji 8 Bicholim-Marcel-Mardol-Ponda 9 Bicholim-MayemLake-Aldona-Mapusa 10 Bicholim-Pilgao-Saptakoteshwar-Narva 11 Bicholim-Poira-Sinquerim-Bicholim 12 Bicholim-Sarmans-Pilgao-Narva 13 Bicholim-Tikhajan-Kerem-Madel 14 Canacona-Palolem-Cab de Ram 15 Canacona-Val-Khangini-Balli-Margao 16 Cuncolim-Vellim 17 Curchorem-Farmagudi 18 Curchorem-Rivona-Vadem 19 Curchorem-Sanguem-Tudva-Verlem 20 Dabe-Mopirla-Fatorpa-Cuncolim-Margao-Panaji 21 Dhada-Maingine-Ponda-Farmagudi 22 Harmal-Mandre-Siolim-Mapusa 23 Ibrampur-Assonora-Bicholim-Advoi-Valpoi 24 Juvem-Kumbharjua-Marcel-Betki-Savoi-Bhatle 25 Kawar-Canacona-Rajbag 26 Mapusa-Aldona-Khorjuve-Goljuve 27 Mapusa-Aldona-Madel 28 Mapusa-Aldona-Poira-Bicholim 29 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Korgao 30 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Sawantwada-Mandre 31 Mapusa-Azilo District Hospital 32 Mapusa-Bastora-Chandanwadi 33 Mapusa-Bicholim-Poira 34 Mapusa-Bicholim-Sankhali-Valpoi-Hivre 35 Mapusa-Calvi-Madel 36 Mapusa-Carona-Amadi 37 Mapusa-Colvale-Dadachiwadi-Madkai 38 Mapusa-Duler-Camurli 39 Mapusa-Karurli-Aldona-Pomburpa-Panaji 40 Mapusa-Khorjuve-Bicholim-Varpal 41 Mapusa-Marna-Siolim 42 Mapusa-Nachnola-Carona-Calvi 43 Mapusa-Palye-Succuro-Bitona-Panaji 44 Mapusa-Panaji-Fatorpha(Sunday) 45 Mapusa-Pedne-Pednekarwada-Mopa 46 Mapusa-Saligao-Calangute-Pilerne-Panaji 47 Mapusa-Siolim