A Reflection on NEP 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. AC Michael, Christian Activist for Human Rights

Endorsed by - (In alphabetical order) 1. A C Michael, Christian Activist For Human Rights And Former Member Delhi Minorities Commission 2. A. Hasan, Retired Banker 3. A. K Singh, NA 4. A. Reyna Shruti, Student 5. A. Giridhar Rao, NA 6. A. M. Roshan, Concerned Citizen 7. A. Selvaraj, Former Chief Commissioner Of Income Tax 8. Aakanksha, Student 9. Aakash Gautam, NA 10. Aakshi Sinha, NA 11. Aastha, Student/Teacher 12. Abde Mannaan Yusuf, Moderator IAD 13. Abdul Ghaffar, Manager, Private Firm 14. Abdul Kalam, NA 15. Abdul Mabood, Citizen 16. Abdul Wahab, Social Activist / Business 17. Abha Choudhuri, Homemaker And Caregiver 18. Abha Dev Habib, Assistant Professor, Miranda House, DU 19. Abha Rani Devi, NA 20. Abha, Research Scholar 21. Abhay Kardeguddi, CEO 22. Abhay, Lawyer 23. Abhijit Kundu, Faculty, DU 24. Abhijit Sinha, Mediaman 25. Abhinandan Sinha, NA 26. Achin Chakraborty, NA 27. Achla Sawhney, NA 28. Adithi, Teacher 29. Aditi Mehta, IAS Retd. 30. Aditya Mukherjee, Professor 31. Aditya Nigam, Academic, Delhi 32. Admiral L Ramdas, Former Chief Of Naval Staff 33. Adnan Jamal, Student 34. Adv. Ansar Indori, Human Rights Lawyer 35. Afaq Ullah, Social Worker 36. Aftab, Advocate 37. Agrima, Student 38. Ahmar Raza, Retired Scientist 39. Aiman Khan, Researcher 40. Aiman Siddiqui, Journalist 41. Aishah Kotecha, Principal 42. Aishwarya Bajpai, Student 43. Aishwarya, NA 44. Ajay Singh Mehta, NA 45. Ajay Skaria, Professor, History And Global Studies, University Of Minnesota 46. Ajay T G, Filmmaker 47. Ajin K Thomas, Researcher, Ahmedabad 48. Ajmal V, Freelance Journalist 49. Akash Bhatnagar, IT 50. Akha, NA 51. -

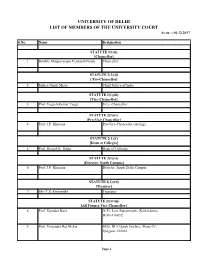

UNIVERSITY of DELHI LIST of MEMBERS of the UNIVERSITY COURT As on :- 04.12.2017

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY COURT As on :- 04.12.2017 S.No. Name Designation STATUTE 2(1)(i) [Chancellor] 1 Hon'ble Muppavarapu Venkaiah Naidu Chancellor STATUTE 2(1)(ii) [ Pro-Chancellor] 2 Justice Dipak Misra Chief Justice of India STATUTE 2(1)(iii) [Vice-Chancellor] 3 Prof. Yogesh Kumar Tyagi Vice -Chancellor STATUTE 2(1)(iv) [Pro-Vice-Chancellor] 4 Prof. J.P. Khurana Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Acting) STATUTE 2(1)(v) [Dean of Colleges] 5 Prof. Devesh K. Sinha Dean of Colleges STATUTE 2(1)(vi) [Director, South Campus] 6 Prof. J.P. Khurana Director, South Delhi Campus STATUTE 2(1)(vii) [Tresurer] 7 Shri T.S. Kripanidhi Treasurer STATUTE 2(1)(viii) [All Former Vice-Chancellor] 8 Prof. Upendra Baxi A-51, Law Appartments, Karkardoma, Delhi-110092 9 Prof. Vrajendra Raj Mehta 5928, DLF Qutab Enclave, Phase-IV, Gurgaon-122002 Page 1 10 Prof. Deepak Nayyar 5-B, Friends Colony (West), New Delhi-110065 11 Prof. Deepak Pental Q.No. 7, Ty.V-B, South Campus, New Delhi-110021 12 Prof. Dinesh Singh 32, Chhatra Marg, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 STATUTE 2(1)(ix) [Librarian] 13 Dr. D.V. Singh Librarian STATUTE 2(1)(x) [Proctor] 14 Prof. Neeta Sehgal Proctor (Offtg.) STATUTE 2(1)(xi) [Dean Student's Welfare] 15 Prof. Rajesh Tondon Dean Student's Welfare STATUTE 2(1)(xii) [Head of Departments] 16 Prof. Christel Rashmi Devadawson The Head Department of English University of Delhi Delhi-110007 17 Prof. Sharda Sharma The Head Department of Sanskrit University of Delhi Delhi-110007 18 Prof. -

Ms.-Arshmeet-Kaur-1.Pdf

Faculty Details Title Mrs. First Name Arshmeet Last Name Kaur Photograph Designation Associate Professor Address 146, Sargodha Apts. Plot 13, Sector 7 Dwarka, New Delhi 110075 Phone No Office 011-26494544 Residence* 9910345900 Mobile* 9910345900 Email [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year B.Sc.(H) MATHEMATICS MIRANDA HOUSE,UNIVERSITY OF DELHI 1987-1990 M.Sc. MATHEMATICS MIRANDA HOUSE ,UNIVERSITY OF DELHI 1990-1992 M.PHIL. MATHEMATICS UNIVERSITY OF DELHI 1992-1994 NET WITH JRF JOINT CSIR-UGC June 1993 Career Profile TEACHING EXPERIENCE: 24 YEARS IN GARGI COLLEGE. PRIOR TO JOINING GARGI 11 MONTHS IN JESUS AND MARY COLLEGE AND 4 MONTHS IN MIRANDA HOUSE, UNIVERSITY OF DELHI Administrative Assignments MEMBER NIRF COMMITTEE(GARGI) 2016-18 ADMISSION CONVENOR FOR HUMANITIES IN 2018 FACULTY ADVISOR MATHEMATICS ASSOCIATION 2016-18 MEMBER OF PATHFINDER COMMITTEE 2014-17 CO-CONVENER B.A. (PROG) ASSOCIATION 2012-13 TEACHER-IN-CHARGE 2010-2012, 2004-06 DEPUTY SUPERINTENDENT OF EXAMINATION 2010-2011 JOINT MENTOR GARGI PATHFINDER PROJECT(COMMERCE) 2009-10 MEMBER OF INTERNAL ASSESSMENT COMMITTEE 2006-09 CONVENER OF PLACEMENT CELL 2004-05 MEMBER OF PRIZE COMMITTEE 2004-06 , 1998-2000 STAFF ADVISOR TO STUDENTS UNION 1995-98 Areas of Interest / Specialization MATHEMATICAL PROGRAMMING Subjects Taught CALCULUS, REAL ANALYSIS, ALGEBRA, DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS, STATISTICS, MULTIVARIATE CALCULUS, LINEAR www.gargi.du.ac.in Page 1 PROGRAMMING AND THEORY OF GAMES Research Guidance Recent Publications LUTHRA V,KAUR A, SAINI S, AHUJA D ,NAGPAL A, PAL M, UNIYAL M, BHARADWAJ A.(2016) AWARENESS AND USE OF FREE/OPEN SOFTWARE FOR SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS EDUCATION IN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES SOCIAL SCIENCE AND EDUCATION,3(11)65-69 LUTHRA V, KAUR A, SAINI S, JAGLAN S, DHASMANA S, APOORVA, and B.P.AJITH EVALUATION OF BOLTZMANN’S CONSTANT: REVISIT USING INTERFACED DATA ANALYSIS BY IN THE PHYSICS EDUCATION, VOL (32), ISSUE 3, ARTICLE NUMBER2, 1-5. -

DEPARTMENT of POLITICAL SCIENCE 2019-20.Docx

DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Department of Political Science has actively and substantively organized a gamut of academic events and programmes throughout the session of 2019-20. On 20th August 2019, the functioning of La Politique, the association of the department, commenced with the orientation programme arranged particularly for the 1st year students of the department. On September 2, 2019, democratically elected Union of the department was formed, with Heena Makwana and Pankaj Yadav elected as the President and Vice President respectively. General Secretary Surabhi Das along with the worthy Joint Secretaries and Executive Council members further glorified the team. On 20th September 2019, La Politique organized an official Fresher’s Welcomeprogramme with a view to promote interaction and bonding among all the students of the department. On 18th October 2019, La Politique in collaboration with North East Students' Cell of Kirori Mal College organized a panel discussion on National Register of Citizens (NRC) and Citizenship Rights. Two eminent penalists, namely, Ms. Sangeeta BarooahPisharoty, Deputy Editor, The Wire and Prof. Apoorvanand, Professor of Hindi, University of Delhi delivered an engaging and enriching session. Enthusiastic participation of students with their inquisitive interventions and critical questioning marked the success of the event. The fresh week of January 2020 witnessed a remarkable session on "The USA and West Asia: Global Implications”. Prof. Sanjeev Kumar HM of University of Delhi was the keynote speaker who delivered an insightful and thought- provoking lecture on the theme. The session was followed by book launch of the book titled “Global Politics”writtenbyDr. RupakDattagupta. La Politique also promoted and facilitated in-house discussion among the students of the department offering them an exposure to democratic culture of debate and deliberation. -

Title: First Name:SHIVALI Subject English English English English Designatio N & Status (Permanen T/Ad-Hoc) from to Adhoc 1

Faculty Profile Title: First Name:SHIVALI Last Name:KHARBANDA Designation: SHIVALI KHARBANDA Department: English Address: D_3/29,Sector 16, Rohini, Delhi Email: [email protected] Web-Page: Educational Qualifications (from Bachelor's Degree): Degree Subject University/ College/Institution Year PhD English University of Delhi Pursuing M.Phil English University of Delhi 2005 MA English English Punjab University, Chandigarh 2003 BA Hons, English English University of Delhi 2000 UGC Net 2005 Experience: Designatio Name of the University/College/ n & Status From To Effective Time Period Institute/Organisation (Permanen t/Ad-hoc) Teaching Mata Sundri College, DU Adhoc 1.8.2006 23.8.2006 23 days Motilal Nehru College, DU Adhoc 15.11.2006 15.7.2007 242 days Jesus and Mary college, DU Adhoc 16.7.2007 15.7.2008 363 days Shyamlal College, DU Permanent 16.7.2008 Present Research/ Corporate Consultancy Teaching - Learning Process (During the Academic Year 2019-2020) Are You using ICT (LMS, E- If Yes, Please give the details below: Resources)? Name Total Numbers E- Resources JSTOR, PROJECT MUSE, RESEARCH GATE, GOOGLE BOOKS,ACADEMIA.EDU Google meet, Zoom, PPTs, Microsoft teams Techniques and Platforms Career Advancement and Contribution to College Corporate Life ( Last three years till June 2020): Name of the Committee/ Centre/ Society/ Cell Designation From To 2020 Students Union Advisory Convener 2019 2020 Fine Arts Member 2019 2019 Students Union Advisory Convener 2018 Convenor/Member of Committees 2019 Fine Arts Member 2018 2018 Canteen Member 2017 2018 Fine Arts Member 2017 Any Other Administrative Responsibility (Bursar, Coordinator, Superintendent etc.) Areas of Interest/Specialisation: S.No. -

Conceptual Plan

Expansion of Leela Hotel at Diplomatic Enclave, Africa Avenue, Netaji Nagar, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi-110023 by M/s Hotel Leelaventure Ltd. Conceptual Plan Consultant-Ascenso Enviro Pvt. Ltd. Page 1 of 24 Expansion of Leela Hotel at Diplomatic Enclave, Africa Avenue, Netaji Nagar, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi-110023 by M/s Hotel Leelaventure Ltd. CONCEPTUAL PLAN 1. INTRODUCTION M/s Hotel Leelaventure Ltd. has gone for Expansion of Leela Hotel at Diplomatic Enclave, Africa Avenue, Netaji Nagar, Chankyapuri, New Delhi-110023. M/s Hotel Leelaventure Ltd. has been allotted the land vide allotment cum conveyance Deed Registration no. 3682 dated 04.04.2008. The copy of Land Documents is attached as Annexure-I. The expansion project is developed on the total plot area of 12,140 m2. The total built up area after expansion is 61,552.64 m2. The development is done in accordance with Delhi Building Bye Laws, 1983. The project had been granted Environmental Clearance for total built-up area of 39,194.98 m2 by Ministry of Environment and Forests, Govt. of India vide letter no. 21-1211/2007-IA.III dated 13.06.2008. The copy of EC Letter is attached as Annexure-II (a). Regular compliance report of the EC is being submitted. The copy of receiving of submission of latest compliance report for December 2015 is attached as Annexure-II (b). Expansion of project had already been completed before the submission of online application for expansion at MOEF&CC, so it is a violation case as per the new notification of MoEF&CC, GOI vide S. -

Violence and Discrimination Against India's Religious Minorities

briefing A Narrowing Space: Violence and discrimination against India's religious minorities Center for Study of Society and Secularism & Minority Rights Group International Friday prayer at the Jama Masjid, New Delhi. Mays Al-Juboori. Acknowledgements events. Through these interventions we seek to shape public This report has been produced with the assistance of the opinion and influence policies in favor of stigmatized groups. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. In recognition of its contribution to communal harmony, CSSS The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of was awarded the Communal Harmony award given by the Minority Rights Group International and the Center for Study Ministry of Home Affairs in 2015. of Society and Secularism, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the Swedish International Development Minority Rights Group International Cooperation Agency. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non-governmental organization (NGO) working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. Our activities are focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent Center for Study of Society and Secularism minority and indigenous peoples. The Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) is a non profit organization founded in 1993 by the celebrated MRG works with over 150 organizations in nearly 50 Islamic scholar Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer. CSSS works in countries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a different states of India. CSSS works for the rights of the year, has members from 10 different countries. -

Annual Report 2016-17 SAS

Annual Report 2017 Honourable guests, members of the college community and my dear students, I heartily welcome you all to the College Annual Day, the Day for which you have really worked hard, right from your academic scores to sports events, from NCC parades to NSS camps, from Departmental societies to the Arts & Culture Society. Well, the day has arrived and we all are here with our distinguished guest and invited dignitaries to appreciate your efforts. It is a pleasure to introduce the chief guest for the day, Prof. J.P.Khurana – Pro-Vice-Chancellor, University of Delhi. Prof. Jitendra P. Khurana is the Pro-Vice-Chancellor of Delhi University. As Head of the Plant and Molecular Biology Department, he was an avid believer in the ability to convert knowledge into practical application for the welfare of human beings. He specializes in Photoperception and Signal Transduction Mechanisms in plants; Plant Hormone Action Mechanisms; Structural and Functional Genomics in Plants. A recipient of the prestigious the Professor Birbal Sahni Medal by the Indian Botanical Society in the year 2011, the Professor Panchanan Maheshwari Memorial Lecture Award by the Indian National Science Academy in the year 2008; and the Prof. Shri Ranjan Memorial Award by the National Academy of Sciences, India in the year 2006; his research Interests and contributions to the field are noteworthy. He was awarded the ‘Tata Innovation Fellowship’ by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India from 2010 to 2013. With over a 150 publications to his credit; his research group has contributed extensively to the area of light perception and signal transduction mechanisms in plants. -

Over 500 Academicians, Activists, Artists and Writers Including Eminent Professors Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Spivak, Barbara Hariss

Over 500 academicians, activists, artists and writers including eminent Professors Noam Chomsky, Gayatri Spivak, Barbara Hariss-White, Michael Davis among others condemn the ongoing state violence and unlawful detention of faculty and student protesters of the University of Hyderabad. We, academicians, activists, artists and writers, condemn the ongoing brutal attacks on and unlawful detention of peacefully protesting faculty and students at the University of Hyderabad by the University administration and the police. We also condemn the restriction of access to basic necessities such as water and food on campus. The students and faculty members of the University of Hyderabad were protesting the reinstatement of Dr. Appa Rao Podile as the Vice-Chancellor despite the ongoing judicial enquiry against him related to the circumstances leading to the death of the dalit student Rohith Vemula on January 17th, 2016. Students and faculty members of the university community are concerned that this may provide him the opportunity to tamper with evidence and to influence witnesses. Suicides by dalit students have been recurring in the University of Hyderabad and other campuses across the country. The issue spiraled into a nationwide students’ protest with the death of the dalit scholar Rohith Vemula. The protests have pushed into the foreground public discussion and debate on the persistence of caste-based discrimination in educational institutions, and surveillance and suppression of dissent and intellectual debate in university spaces. Since the morning of March 22 when Dr. Appa Rao returned to campus, the students and staff have been in a siege-like situation. The peacefully protesting staff and students were brutally lathi-charged by the police, and 27 people were taken into custody. -

Vasvi Bharat Ram

VASVI BHARAT RAM EXPERIENCE 2017-18- National President FLO 2016 – National Sr. Vice President, Ficci Ladies Organisation 2015 – National Vice President, Ficci Ladies Organisation 2013 - Present : Member, Education Committee, FICCI. 2011 - Present : Vice Chairperson of The Shri Ram Schools. 2010 - 2011 : Chairperson, Young Ficci Ladies Organisation. 2010 - Present : Board Member, SRF Foundation. 2009 - Present : Member of the Management Committee of The Shri Ram Millenium Schools. 2009 - Present : Governing Body member of Ficci Ladies Organisation. 1995 - 1997 : Innoways - own business making Wrought Iron furniture, gates, grills, home accessories and artifacts for the local market. 1993 - 1995 : worked in 2 Buying and Merchandising Fashion Export Companies taking care of European Market. EDUCATION 2013 : One Week Executive Education Program, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Boston. 1991 - 1993 : Business of Fashion Management, Post Graduate Diploma, London College of Fashion, London. 1988 - 1991 : Sociology, B.A. Honours Jesus and Mary College, Delhi Univesity, New Delhi. 1975 - 1988 : Modern School, Vasant Vihar, New Delhi. ACCOMPLISHMENTS 2013 – 2014 : Education Chair, YPO Delhi Chapter. Won the Award for the Best Education Year amongst all the 11 Chapters in YPO South Asia. 2011 - 2013 : Board Member, YPO Delhi Chapter. Spouse Forum Coordinator, won an Award for Best Spouse Forum Coordinator, International. 2010 – 2011 : Chairperson, Young Ficci Ladies Organisation, Delhi LANGUAGES English Hindi INTERESTS Reading Travelling Music Theatre PERSONAL DETAILS Date of Birth - 9th March 1971 Marital Status - Married with 2 Daughters Ph: +91 – 99712 86969 E: [email protected] Age: 49 years Synopsis Harjinder is National Vice president of FLO.She founded her company in 1995. Today with 70+ employees and 4 offices across India, it makes her a proud business Woman providing operational, strategic and administrative leadership in challenging situations. -

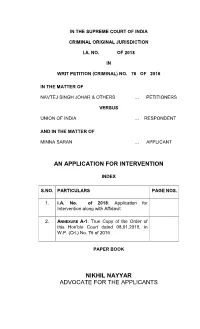

An Application for Intervention Nikhil Nayyar Advocate for the Applicants

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION I.A. NO. OF 2018 IN WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 76 OF 2016 IN THE MATTER OF NAVTEJ SINGH JOHAR & OTHERS … PETITIONERS VERSUS UNION OF INDIA … RESPONDENT AND IN THE MATTER OF MINNA SARAN … APPLICANT AN APPLICATION FOR INTERVENTION INDEX S.NO. PARTICULARS PAGE NOS. 1. I.A. No. of 2018: Application for Intervention along with Affidavit 2. ANNEXURE A-1: True Copy of the Order of this Hon’ble Court dated 08.01.2018, in W.P. (Crl.) No. 76 of 2016 PAPER BOOK NIKHIL NAYYAR ADVOCATE FOR THE APPLICANTS 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CRIMINAL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION I.A. NO. OF 2018 IN WRIT PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO. 76 OF 2016 IN THE MATTER OF NAVTEJ SINGH JOHAR & OTHERS … PETITIONERS VERSUS UNION OF INDIA … RESPONDENT AND IN THE MATTER OF Minna Saran, aged 62 years, Residing at E 301 Krishna Apra Residency, Sector 61, Noida ... APPLICANT AN APPLICATION FOR INTERVENTION To, The Hon’ble Chief Justice of India and His Companion Justices of the Supreme Court of India The Humble Application of the Applicant abovenamed Most Respectfully Submits : 1. That on 11th December 2013, in Suresh Kumar Koushal and another v. Naz Foundation and others (2014) 1 SCC 1, a two-judge bench of this Hon’ble Court allowed an appeal against the decision of the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi in Naz Foundation v. Govt. of Delhi in NCT (2009) 160 DLT 277, which had decided a challenge to the constitutional validity of 2 Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. -

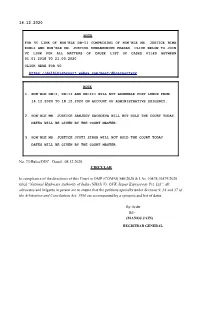

14.12.2020 No. 73/Rules/DHC Dated

14.12.2020 NOTE FOR VC LINK OF HON'BLE DB-II COMPRISING OF HON'BLE MS. JUSTICE HIMA KOHLI AND HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SUBRAMONIUM PRASAD. CLICK BELOW TO JOIN VC LINK FOR ALL MATTERS OF CAUSE LIST OF CASES FILED BETWEEN 01.01.2018 TO 21.03.2020 CLICK HERE FOR VC https://delhihighcourt.webex.com/meet/dhcecourtvc2 NOTE 1. HON'BLE DB-I, DB-II AND DB-III WILL NOT ASSEMBLE POST LUNCH FROM 14.12.2020 TO 18.12.2020 ON ACCOUNT OF ADMINISTRATIVE EXIGENCY. 2. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJEEV SACHDEVA WILL NOT HOLD THE COURT TODAY. DATES WILL BE GIVEN BY THE COURT MASTER. 3. HON'BLE MS. JUSTICE JYOTI SINGH WILL NOT HOLD THE COURT TODAY. DATES WILL BE GIVEN BY THE COURT MASTER. No. 73/Rules/DHC Dated : 08.12.2020 CIRCULAR In compliance of the directions of this Court in OMP (COMM) 540/2020 & I.As. 10478,10479/2020 titled “National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) Vs. GVK Jaipur Expressway Pvt. Ltd”, all advocates and litigants in person are to ensure that the petitions specially under Sections 9, 34 and 37 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 are accompanied by a synopsis and list of dates. By Order Sd/- (MANOJ JAIN) REGISTRAR GENERAL NOTE 1.THE MATTERS LISTED DURING THE PERIOD OF LOCKDONW i.e., W.E.F. 22.03.2020 BE SHOWN UNDER THE HEADING “SUPPLEMENTARY LIST(S)”. 2.THE MATTERS FILED BETWEEN 01.01.2018 TO 21.03.2020, BE SHOWN UNDER THE HEADING “CAUSE LIST OF CASES FILED BETWEEN 01.01.2018 TO 21.03.2020.