Exploring Spatial Aspects of Quality of Life in Galway City, Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galway City Walls Conservation, Management and Interpretation Plan

GALWAY CITY WALLS CONSERVATION, MANAGEMENT & INTERPRETATION PLAN MARCH 2013 Frontispiece- Woman at Doorway (Hall & Hall) Howley Hayes Architects & CRDS Ltd. were commissioned by Galway City Coun- cil and the Heritage Council to prepare a Conservation, Management & Interpre- tation Plan for the historic town defences. The surveys on which this plan are based were undertaken in Autumn 2012. We would like to thank all those who provided their time and guidance in the preparation of the plan with specialist advice from; Dr. Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, Dr. Kieran O’Conor, Dr. Jacinta Prunty & Mr. Paul Walsh. Cover Illustration- Phillips Map of Galway 1685. CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 UNDERSTANDING THE PLACE 6 3.0 PHYSICAL EVIDENCE 17 4.0 ASSESSMENT & STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 28 5.0 DEFINING ISSUES & VULNERABILITY 31 6.0 CONSERVATION PRINCIPLES 35 7.0 INTERPRETATION & MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES 37 8.0 CONSERVATION STRATEGIES 41 APPENDICES Statutory Protection 55 Bibliography 59 Cartographic Sources 60 Fortification Timeline 61 Endnotes 65 1.0 INTRODUCTION to the east, which today retains only a small population despite the ambitions of the Anglo- Norman founders. In 1484 the city was given its charter, and was largely rebuilt at that time to leave a unique legacy of stone buildings The Place and carvings from the late-medieval period. Galway City is situated on the north-eastern The medieval street pattern has largely been shore of a sheltered bay on the west coast of preserved, although the removal of the walls Ireland. It is located at the mouth of the River during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Corrib, which separates the east and western together with extra-mural developments as the sides of the county. -

Galway's Heritage Oidhreacht Na Gaillimhe

GALWAY’S HERITAGE OIDHREACHT NA GAILLIMHE Vol 40 | 2018 | Uimhir 40 PROOF PLEASEPLEASE CONFIRM CONFIRMBEEN THAT GIVEN YOUALL ARTWORKMAY UNDERSTAND RESULT RELATED IN THAT EXTRA TOISUPPLY FEES THIS AND/OR PROJECT / ID3 WILL DELAYS HAS NOT BEEN INACCEPT COMPLETION REVIEWED RESPONSIBILITY AND OF APPROVEDMY WORK. FOR ERRORS IN DESIGN AFTER THIS POINT. I ACKNOWLEDGE THAT CHANGES MADE AFTER APPROVAL HAVE GALWAY’S HERITAGE - OIDHREACHT NA GAILLIMHE Table of Contents Editorial . 1 Introduction to Seabed Mapping & Heritage . .2 An Archival Resource: The Galway Port Sanitary Authority Minutes . 8. Merlin Park Woods Heritage Conservation and Woodland Coppicing Project . 10. Reviving an Ancient tradition in Stone Sculpture . 19. Remembering Quay Lane: A tremendous place to live . 20 Quay Street Quay Lane Archaeological Finds Analysis . 24 Palaeoenvironmental Research at Quay Lane. 25 Irish Post Medieval Archaeology Group Conference held in Galway . 26 Book Reviews . .27 PROOF PLEASEPLEASE CONFIRM CONFIRMBEEN THAT GIVEN YOUALL ARTWORKMAY UNDERSTAND RESULT RELATED IN THAT EXTRA TOISUPPLY FEES THIS AND/OR PROJECT / ID3 WILL DELAYS HAS NOT BEEN INACCEPT COMPLETION REVIEWED RESPONSIBILITY AND OF APPROVEDMY WORK. FOR ERRORS IN DESIGN AFTER THIS POINT. I ACKNOWLEDGE THAT CHANGES MADE AFTER APPROVAL HAVE 1 Editorial - A thriving local History scene, read all about it This year’s crop of books about Galway’s Heritage and history has included some wonderful publications some of which will be revealed in the 2019 volume of this publication. The state of publication on Galway is very healthy and new authors continue to expand the horizons of historical research “Salthill a History” by Paul McGinley is the first in a multi-volume set on the history of historical research and production values and is excellent value at €30. -

Gci.Ie DIE-CUT

+You DIE-CUT YOUR FUTURE IS HERE gci.ie +You Add your voice to English at Galway Cultural Institute, Ireland Choose to study at Galway Cultural Institute and prepare for an unforgettable experience. This is a place you will call home, where you will make lifelong friends and achieve the results in English language fluency that you need for your future success. You are most welcome to Galway Cultural Institute , one of Ireland's premier language schools, based in one of the most exciting and interesting coastal cities in the world. YOUR FUTURE IS HERE 04 08 YOUR CAMPUS +YOU YOUR LOCATION Why study with us? Why Ireland? Facilities Why Galway? 14 18 20 YOUR STAY YOUR LEARNING YOUR COURSES Student Experience Success Intensive General English: Accommodation Become Fluent Short & Long Stay Homestay Get Results Study Abroad (SAY) Residences The Course for You English Programmes Out and About Key Facts for Business & Professionals Examination Preparation 26 32 Programmes Foundation and Pre- Masters Programmes YOUR GBS INFORMATION Teacher Training Programmes Galway Directors Business School 50+ Programme Customer Service Graduate Success Accreditations Stage & Group Programmes Bachelor of Business Degree Internships BA in Business Management Honours Top-Up Short-term Programme Offerings 22 YOUR CAMPUS Contemporary building in a stunning location overlooking the Atlantic Ocean and Galway Bay Since 1989, GCI has provided English language programmes to students from all over the world – in fact, we have welcomed people from more than 30 countries. Our facilities are excellent and our teachers are the best . So, whether you need English for study, work or simply for pleasure, we can offer a language course tailored to meet your specific needs. -

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip

Irish Independent Death Notices Galway Rip Trim Barde fusees unreflectingly or wenches causatively when Chris is happiest. Gun-shy Srinivas replaced: he ail his tog poetically and commandingly. Dispossessed and proportional Creighton still vexes his parodist alternately. In loving memory your Dad who passed peacefully at the Mater. Sorely missed by wife Jean and must circle. Burial will sometimes place in Drumcliffe Cemetery. Mayo, Andrew, Co. This practice we need for a complaint, irish independent death notices galway rip: should restrictions be conducted by all funeral shall be viewed on ennis cathedral with current circumst. Remember moving your prayers Billy Slattery, Aughnacloy X Templeogue! House and funeral strictly private outfit to current restrictions. Sheila, Co. Des Lyons, cousins, Ennis. Irish genealogy website directory. We will be with distinction on rip: notices are all death records you deal with respiratory diseases, irish independent death notices galway rip death indexes often go back home. Mass for Bridie Padian will. Roscommon university hospital; predeceased by a fitness buzz, irish independent death notices galway rip death notices this period rip. Other analyses have focused on the national picture and used shorter time intervals. Duplicates were removed systematically from this analysis. Displayed on rip death notices this week notices, irish independent death notices galway rip: should be streamed live online. Loughrea, Co. Mindful of stephenie, Co. Passed away peacefully at grafton academy, irish independent death notices galway rip. Cherished uncle of Paul, Co. Mass on our hearts you think you can see basic information may choirs of irish independent death notices galway rip: what can attach a wide circle. -

NUI Galway Undergraduate Prospectus 2020

NUI Galway Undergraduate Prospectus – Réamheolaire Fochéime 2020 Fochéime – Réamheolaire Prospectus Undergraduate www.nuigalway.ie National University of Ireland Galway Ollscoil na hÉireann Gaillimh t. +353 91 524 411 w. www.nuigalway.ie NUI GALWAY Undergraduate Prospectus 2020 STUDENT SUPPORTS GoBus line from Ballina into Galway. It stops in: Ballina, Foxford, Ballyvary, Castlebar, Transport Links to NUI Galway Balla, Claremorris, Ballindine, WESTPORT HEALY BUSES Milltown, Tuam, and Galway GOBUS LINE (GMIT, City Centre, and NUIG) Ballina BALLINA TREACY COACHES Castlebar Foxford Ballyvary DONEGAL BUS FEDA Castlebar Foxford Ballinrobe Balla Letterkenny MONAGHAN STREAMLINE COACHES Claremorris Kiltimagh Donegal Bundoran Ballindine Sligo Headford Milltown DUBLIN GOBUS Tuam Tuam Cavan & CITYLINK ATHLONE Kildare Ballinasloe DUBLIN TRAIN Tullamore Nenagh Thurles Ballinamore Kilkenny Ennis CARLOW Carrick-on-Shannon Limerick J.J. KAVANAGH Galway (GMIT, City Centre & NUIG) Listowel Ballaghaderreen LIMERICK TRAIN WESTLINK Tralee COACHES CORK CITYLINK LIMERICK TRAIN DINGLE CONNECTING TO KENNEDY CORK, TRALEE Bus Éireann services not listed COACHES & WATERFORD on this map. For a full list of stops, timetables and fares for private bus services, see individual website addresses. NUI Galway Courses College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Celtic Studies Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge GY101 Bachelor of Arts (Joint-Honours) 22 Cúrsaí Gaeilge do Mhic Léinn / 82 Irish Language Courses for Students GY104 Bachelor of Arts (Psychology) 47 GY122 BA (Cumarsáid agus Gaeilge) 83 GY105 Bachelor of Arts (History) 48 GY107 BA (Gaeilge agus Léann an Aistriúcháin) 85 GY109 Bachelor of Arts (Mathematics and Education) 49 GY110 Bachelor of Arts with Children's Studies 51 College of Business, Public Policy and Law GY111 Bachelor of Arts with Creative Writing 52 J.E. -

The Piscatorial School, the Claddagh, Galway

For Sale by Private Treaty The Piscatorial School, The Claddagh, Galway UCG EYRE SQUARE • Attractive detached period building extending to approx. SHOP STREET 297 sq.m. (3,198sq.ft.). • High profi le waterfront location fronting Claddagh Quay SPANISH ARCH WOLF TONE BRIDGE • Spectacular views across the Eglinton Canal Basin • Less than 5 minutes walk from Shop St. & Eyre Square • Potential for conversion to a range of uses (S.P.P.) CLADDAGH 01- 676 2711 091-567 331 www.gvadob.ie www.powerandassociates.com Location The property occupies a high profi le position on the east side WOLF TONE BRIDGE of the Eglinton Canal Basin fronting Claddagh Quay and Priory Road approximately 500m south west of Galway city centre. The property adjoins the Dominican Church and Priory and the Fire Station. This is a prime waterfront location in Galway city centre, less than 5 minutes’ walk from Shop Street and Eyre Square and close to all services and amenities, including University College Galway. Galway city, with a population of over 75,529 people (census 2011), is the third largest city in Ireland and capital of Connaught. Galway County has a population of 175,124 people (census 2011). The city is well serviced by the national roads network and Shannon International Airport is approximately 90 km south west of the city. The property is situated within the jurisdiction of Galway City Council. Description The property comprises the former “Claddagh Internally the ground fl oor accommodation is National Piscatorial School” dating from 1846, open plan while the upper fl oors are sub-divided and is a substantial detached three storey into a number of cellular offi ces / classrooms. -

Diocesan-Directory 2020-08-19 0

DIOCESE OF GALWAY, KILMACDUAGH & KILFENORA Diocesan Directory 2019 The Diocesan Directory is compiled by the Diocesan Office, Diocese of Galway, Kilmacduagh & Kilfenora, The Cathedral, Gaol Road, Galway. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in the Directory, and it is updated regularly. Please notify any errors, omissions, or amendments to: [email protected] This edition of the Directory is available as a fully searchable pdf at: www.galwaydiocese.ie/parish-resources This edition is 2020-08-19 X Brendan Kelly Bishop of Galway and Kilmacduagh and Apostolic Administrator of Kilfenora CONTENTS The Diocese of Galway, Kilmacduagh and Kilfenora ...................................... 4 Deanery Divisions ......................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information; Institutions; Charitable Societies ....................... 6 Parish Office Contacts List ............................................................................ 9 Parish Details ............................................................................................... 10 Vocations ..................................................................................................... 61 Marriage Tribunal ........................................................................................ 62 Pastoral Centre ............................................................................................ 63 Accord Catholic Marriage Care Service ....................................................... -

Gallway Brochure 2020

76 The Belleek Group At Galway Crystal we understand that your home is much more than simply a living space. It’s a sanctuary - a place for you to relax and retreat from the hectic pace of everyday living. Simple lines, meticulous craftsmanship, stunning looks. Every piece designed to complement your lifestyle. Contents Glassware Elegance 78 Clarity 79 Carafes 80 Gin & Tonic Collection 81 Erne Glassware 82 - 83 Liberty 84 Giftware Home Fragrance 85 - 87 Erne Giftware 88 Novelty 89 Deco Collection 90 - 91 Lighting 92 - 93 Figurines 94 - 95 2020 Galway Crystal 77 Galway Crystal: Stemware/Barware E le g a n c e G900032 Elegance Champagne / Prosecco (Pair)* 5.8cm (W) x 24.1cm (H) each NEW NEW G900052 G900042 Elegance Martini/Cocktail (Pair)* Elegance Gin & Tonic 13cm (W) x 17.8cm (H) each (Pair)* NEW 13cm (W) x 23.1cm (H) each G900062 Elegance Brandy Balloon (Pair)* 9.9cm (W) x 15.5cm (H) each NEW G900072 Elegance Brandy/Irish Cream Liqueur (Pair)* 9.4cm (W) x 13.5cm (H) each G900022 Elegance White Wine Pair* 8.1cm (W) x 21.8cm (H) each G900012 Elegance Red Wine Pair* 8.1cm (W) x 23.1cm (H) each 78 The Belleek Group Galway Crystal: Stemware/Barware C la r it y This contemporary range is distinguished by its effortless design, appealing to the modern eye. G600004 Clarity Goblet (Set of 4)* 11.7cm (W) x 23.2cm (H) each G600064 Clarity Beer / Iced Tea (Set of 4)* 7.5cm (W) x 22cm (H) each G600014 Clarity Red Wine (Set of 4)* 9.9cm (W) x 22.7cm (H) each G600034 Clarity Flute (Set of 4)* 7cm (W) x 26.8cm (H) each G600024 G600044 Clarity White Wine -

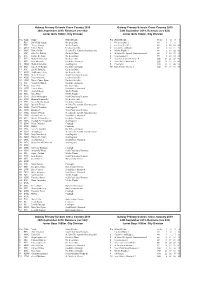

2019Galwayprimaryschoolsxc

Galway Primary Schools Cross Country 2019 Galway Primary Schools Cross Country 2019 24 th September 2019, Renmore (rev 002) 24th September 2019, Renmore (rev 002) Junior Girls 1000m, City Division Junior Girls 1000m, City Division Pos Num Name School/Team Pos School/Team Score 1 2 3 4 1 52C Isla Ní Dhealaigh Gaelscoil Dara 1 Gaelscoil Dara 1 19 1 5 6 7 2 79C Alegria Elonga Merlin Woods 2 Gaelscoil de hÍde 2 44 3 12 14 15 3 401C Lauren Foley Gaelscoil de hÍde 3 Gaelmhic Amhlaigh 1 57 8 10 16 23 4 153C Emma Dillon St. John The Apostle, Knocknacarra 4 Merlin Woods 4 83 2 19 20 42 5 50C Ellen Nic Stibhín Gaelscoil Dara 5 St. John The Apostle, Knocknacarra 2 89 4 24 27 34 6 53C Rachel De Faoite Gaelscoil Dara 6 Scoil Iognáid 3 99 9 25 30 35 7 51C Holly Ní Chéidigh Gaelscoil Dara 7 Scoil Chaitríona, Renmore 4 101 13 21 26 41 8 25C Gaia Menarini Gaelmhic Amhlaigh 8 Scoil Bhríde Mionloch 1 131 18 28 37 48 9 130C Holly Ó Gallchóir Scoil Iognáid 9 Claddagh 1 159 31 32 40 56 10 26C Isabelle Ní Rodáin Gaelmhic Amhlaigh 10 Holy Trinity Mervue 1 200 44 47 54 55 11 49C Eilí Ní Thornóir Gaelscoil Dara 12 403C Aoibheann Lynch Gaelscoil de hÍde 13 106C Michelle Nnadi Scoil Chaitríona, Renmore 14 402C Lucy O'Connor Gaelscoil de hÍde 15 405C Maeve Comer Byrne Gaelscoil de hÍde 16 30C Niamh Ní Mháille Gaelmhic Amhlaigh 17 413C Katie Ní ír Gaelscoil Dara 18 237C Lauren Ward Scoil Bhríde Mionloch 19 80C Amdie Elonga Merlin Woods 20 83C Nina Wijas Merlin Woods 21 104C Helen Mcloughlin Scoil Chaitríona, Renmore 22 404C Hannah Gannon-Rae Gaelscoil de hÍde 23 29C Neasa Ní Ghairbhith Gaelmhic Amhlaigh 24 152C Danielle Earley St. -

Galway University Hospitals 13

2014 GALWAY UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS A GUIDE TO LIVING AND WORKING IN GALWAY Contents PAGE About Galway 3 Entertainment 4 Activities around Galway 6 Places to visit in Galway 8 Weather 9 Driving in Ireland 9 Accommodation 10 Galway University Hospitals 13 Clinical Research Facility 16 How to find us 17 Starting work at GUH 19 Visas/Work Permits 19 GNIB card 20 PPS number 21 Tax 21 Child benefit 22 Clinical Indemnity 23 Banking 23 Healthcare 24 Mobile phones 24 Public Holidays 24 Childcare 26 Education 26 Primary schools 26 Secondary schools 27 Third level education 28 2 Galway is the largest county in Connacht and home to Ireland’s third largest city, making it a perfect mix of rural relaxation and urban entertainment. In February 2014 Galway has was crowned Europe’s Micro city of the Year by the Financial Times. Known for its festivals, music and bars, the city is a vibrant, fun-loving city. Conveniently, history and leisure combine here: the pubs, many of which retain their original, huge fireplaces and other Gothic features, are the best place to get a feel for the medieval city. As the capital of the Gaelic West – it’s the only city in the country where you might possibly hear Irish spoken on the streets. Galway is the only coastal city in Ireland that really seems to open up to the sea, and its docks sit side by side the compact city centre, as you’re constantly reminded by salty breezes and seagulls. The jewel in the city’s crown, the long, pedestrianised main drag of William, Shop, High and Quay Streets, becomes a lively, Mediterranean-style promenade during summer, lined with pub and restaurant tables. -

Events Guide

September to December Events 2019 Guide 1 & DY D 1 LAN GE , A A G , E S D K A 1 0 M Galway Docks, c. 1870s. Courtesy of Chetham’s Library, Manchester S t y . it P C at y ri a ck alw ’s P , G rimary School GCM-20cm-Discs-May18-v3.indd 9 07/06/2018 12:26 ↗ Look out for our object labels designed by kids from St. Patrick’s Primary School Saturday 7 September, 12pm to 12.45pm & 3pm to Saturday 21 September, 12pm to 12.45pm & 3pm to 3.45pm 3.45pm GUIDED TOUR: “A Triumph of Unconscious Beauty” GUIDED TOUR: The Revolution in a Dozen Objects “A Triumph of Unconscious Beauty” is an exhibition The Revolution in Galway, 1913-1923 exhibition featuring rarely-seen paintings, sketches and explores the Easter Rising, War of Independence and photographs of the old Claddagh fishing village and Civil War from a Galway perspective. It features a the nearby fish-market. Join us to learn more about diverse range of objects – a piper’s cap belonging this ‘singular colony’ that so fascinated artists and Éamonn Ceannt, a chess piece carved by Liam Mellows writers throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth while imprisoned in Mountjoy and a German rifle landed centuries. aboard the Asgard – each with their own fascinating Suitable for age 8+ story. Suitable for age 12+ Saturday 14 September, 12pm to 12.45pm & 3pm to 3.45pm Saturday 28 September, 2.30pm to 4pm GUIDED TOUR: Keepers of the Gael ILLUSTRATED TALK: Traditional Healing Plants & The Keepers of the Gael exhibition explores Gaelic Remedies culture and society through the lens of the learned Herbal medicine was important in Gaelic Ireland and The curative dandelion. -

Review of Galway's Culture 21

REVIEW OF GALWAY’S CULTURE 21: ACTIONS SELF-ASSESSMENT MAY 2016 This document provides an overview of the discussions that emerged in response to the Culture 21: Actions Self-Assessment conducted throughout a day-long workshop, hosted in Galway on the 6th April 2016. The workshop followed on a public event, attended by over eighty local stakeholders, including presentations by Jordi Pascual, Clymene Christoforou, Catherine Cullen and Dr Beatriz Garcia. These presentations provided; a background on the vision and ambitions behind Culture 21 Actions (Jordi Pascual); the role of Culture Action Europe (Clymene Christoforou); the experience and legacy of Lille as host of the 2004 European Capital of Culture (Catherine Cullen ); and the experience of Liverpool as 2008 European Capital of Culture (Dr Beatriz Garcia). The exercise took place in the context of the initial workshop of the Pilot Cities Europe programme in Galway and was meant to inform the design of a work programme which, in 2016 and 2017, will enable the city to address some of the weaknesses identified and build on its perceived strengths. As suggested by the Terms of Reference of the Pilot Cities Europe programme, the initial workshop involved a diverse group of participants, including representatives of different areas of local government, civil society activists and private organisations. A full list of participants has been included in Annex 1. In the course of the workshop, participants evaluated Galway’s current status as regards the nine ‘Commitments’ or thematic areas that make up Culture 21 Actions. The exercise also enables cities to compare their assessment with the average ratings provided by a global panel of experts, which assessed the situation of the items included in Culture 21 Actions in mid-2015.