Cartography in the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Erwin Raisz' Atlases

Erwin Raisz‘ Atlases – an early multi-method approach to cartographic communication (Eric Losang) ICC-Preconference-Workshop: Atlases and Infographics Tokyo, 2019/ 07/ 13 Outline • Erwin Raisz – biography and opus • The concept behind Raisz‘ work • Three Atlases • Atlas of Global Geography • Atlas of Cuba • Atlas of Florida • Possible Importance of the three Atlases • Communication • Storytelling Biography • * 1 March 1893, Lőcse, Hungary • 1914 degree in civil engineering and architecture Royal Polytechnicum in Budapest • 1923 Immigration US • 1924/1929 Master/Ph.D. Geology, Columbia University • 1931 Institute of Geographical Exploration at Harvard University (proposed by W. M. Davies, teaching Cartography) • 1938 General Cartography (first cartographic textbook in English) • 1951 Clark University, Boston; from 1957 University of Florida • + 1968, Bangkok while travelling to the IGU in Dehli. Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. Fenneman (physiographic provinces) • Goal: explaining territory within its physiographic instead of (man made) county borders Landform (physiographic) Maps Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. Fenneman (physiographic provinces) • Goal: explaining territory within its physiographic instead of (man made) county borders • Geodeterministic answer to a prevailling statistical approach to geography (H. Gannett) Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. Fenneman (physiographic provinces) • Goal: explaining territory within its physiographic instead of (man made) county borders • Geodeterministic answer to a prevailling statistical approach to geography (H. Gannett) • Method: Delineate the significant elements of the terrain in pictorial-diagrammatic fashion Statistical atlas of the United States 1898 Landform (physiographic) Maps • Influenced by W.M. Davies, I. Bowman and N. -

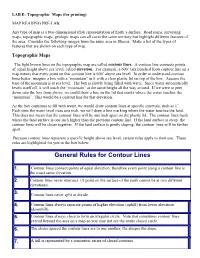

General Rules for Contour Lines

6/30/2015 EASC111LabEFor Printing LAB E: Topographic Maps (for printing) MAP READING PRELAB: Any type of map is a twodimensional (flat) representation of Earth’s surface. Road maps, surveying maps, topographic maps, geologic maps can all cover the same territory but highlight different features of the area. Consider the following images from the same area in Illinois. Make a list of the types of features that are shown on each type of map. Topographic Maps The light brown lines on the topographic map are called contour lines. A contour line connects points of equal height above sea level, called elevation. For example, a 600’ (six hundred foot) contour line on a map means that every point on that contour line is 600’ above sea level. In order to understand contour lines better, imagine a box with a “mountain” in it with a clear plastic lid on top of the box. Assume the base of the mountain is at sea level. The box is slowly being filled with water. Since water automatically levels itself off, it will touch the “mountain” at the same height all the way around. If we were to peer down into the box from above, we could draw a line on the lid that marks where the water touches the “mountain”. This would be a contour line for that elevation. As the box continues to fill with water, we would draw contour lines at specific intervals, such as 1”. Each time the water level rises one inch, we will draw a line marking where the water touches the land. -

Maps and Charts

Name:______________________________________ Maps and Charts Lab He had bought a large map representing the sea, without the least vestige of land And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be, a map they could all understand - Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark Map Projections: All maps and charts produce some degree of distortion when transferring the Earth's spherical surface to a flat piece of paper or computer screen. The ways that we deal with this distortion give us various types of map projections. Depending on the type of projection used, there may be distortion of distance, direction, shape and/or area. One type of projection may distort distances but correctly maintain directions, whereas another type may distort shape but maintain correct area. The type of information we need from a map determines which type of projection we might use. Below are two common projections among the many that exist. Can you tell what sort of distortion occurs with each projection? 1 Map Locations The latitude-longitude system is the standard system that we use to locate places on the Earth’s surface. The system uses a grid of intersecting east-west (latitude) and north-south (longitude) lines. Any point on Earth can be identified by the intersection of a line of latitude and a line of longitude. Lines of latitude: • also called “parallels” • equator = 0° latitude • increase N and S of the equator • range 0° to 90°N or 90°S Lines of longitude: • also called “meridians” • Prime Meridian = 0° longitude • increase E and W of the P.M. -

Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914

Delineating Dominion: Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert H. Clemm Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor Alan Beyerchen Ousman Kobo Copyright by Robert H Clemm 2012 Abstract This dissertation documents the ways in which cartography was used during the Scramble for Africa to conceptualize, conquer and administer newly-won European colonies. By comparing the actions of two colonial powers, Germany and Britain, this study exposes how cartography was a constant in the colonial process. Using a three-tiered model of “gazes” (Discoverer, Despot, and Developer) maps are analyzed to show both the different purposes they were used for as well as the common appropriative power of the map. In doing so this study traces how cartography facilitated the colonial process of empire building from the beginnings of exploration to the administration of the colonies of German and British East Africa. During the period of exploration maps served to make the territory of Africa, previously unknown, legible to European audiences. Under the gaze of the Despot the map was used to legitimize the conquest of territory and add a permanence to the European colonies. Lastly, maps aided the capitalist development of the colonies as they were harnessed to make the land, and people, “useful.” Of special highlight is the ways in which maps were used in a similar manner by both private and state entities, suggesting a common understanding of the power of the map. -

Recent Publications 1984 — 2017 Issues 1 — 100

RECENT PUBLICATIONS 1984 — 2017 ISSUES 1 — 100 Recent Publications is a compendium of books and articles on cartography and cartographic subjects that is included in almost every issue of The Portolan. It was compiled by the dedi- cated work of Eric Wolf from 1984-2007 and Joel Kovarsky from 2007-2017. The worldwide cartographic community thanks them greatly. Recent Publications is a resource for anyone interested in the subject matter. Given the dates of original publication, some of the materi- als cited may or may not be currently available. The information provided in this document starts with Portolan issue number 100 and pro- gresses to issue number 1 (in backwards order of publication, i.e. most recent first). To search for a name or a topic or a specific issue, type Ctrl-F for a Windows based device (Command-F for an Apple based device) which will open a small window. Then type in your search query. For a specific issue, type in the symbol # before the number, and for issues 1— 9, insert a zero before the digit. For a specific year, instead of typing in that year, type in a Portolan issue in that year (a more efficient approach). The next page provides a listing of the Portolan issues and their dates of publication. PORTOLAN ISSUE NUMBERS AND PUBLICATIONS DATES Issue # Publication Date Issue # Publication Date 100 Winter 2017 050 Spring 2001 099 Fall 2017 049 Winter 2000-2001 098 Spring 2017 048 Fall 2000 097 Winter 2016 047 Srping 2000 096 Fall 2016 046 Winter 1999-2000 095 Spring 2016 045 Fall 1999 094 Winter 2015 044 Spring -

Climate Change Adaptation and Natural Disasters Preparedness in the Coastal Cities of North Africa

Arab Republic of Egypt Kingdom of Morocco THE WORLD Republic of Tunisia BANK Climate Change Adaptation and Natural Disasters Preparedness in the Coastal Cities of North Africa Phase 1 : Risk Assessment for the Present Situation and Horizon 2030 – Alexandria Area Draft Final Version 31 January 2011 Project Web Site: http://www.egis-bceominternational.com/pbm/ AASTMT / Egis Bceom Int. / IAU-IDF / BRGM Document quality information Document quality information General information Author(s) AASTMT / Egis BCEOM International Project name Climate Change Adaptation and Natural Disasters Preparedness in the Coastal Cities of North Africa Document name Phase 1 : Risk Assessment for the Present Situation and Horizon 2030 – Alexandria Area Date 31 January 2011 Reference GED 80823T Addressee(s) Sent to: Name Organization Sent on (date): A. Bigio The World Bank 31 January 2011 Copy to: Name Organization Sent on (date): S. Rouhana The World Bank 31 January 2011 A. Tiwari The World Bank 31 January 2011 A. Amasha AASTMT 31 January 2011 History of modifications Version Date Written by Approved & signed by: AASTMT / Egis BCEOM Version 1 13 June 2010 International AASTMT / Egis BCEOM Version 2 06 August 2010 International 05 December AASTMT / Egis BCEOM Version 3 2010 International Climate Change Adaptation and Natural Disasters Preparedness Page 2 in the Coastal Cities of North Africa Draft Final Version AASTMT / Egis Bceom Int. / IAU-IDF / BRGM Document quality information Supervision and Management of the Study The present study is financed by the World Bank as well as the following fiduciary funds: NTF- PSI, TFESSD and GFDRR, which are administered by the World Bank. -

2/1-Spaltig, Ohne Einrückungen

Der Nachlass von Wilhelm Lauer im Archiv des Geographischen Instituts Bonn Findbuch bearbeitet von Sabine KROLL und Jens Peter MÜLLER 2., um Nachträge erweiterte Fassung Bonn 2019 Gefördert von der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft Inhaltsverzeichnis Abkürzungsverzeichnis ............................................................................................................................. II Vorwort .................................................................................................................................................... III Zur Biographie von Wilhelm Lauer ...................................................................................................... III Hinweise zum Nachlass Lauer und zur Benutzung ............................................................................. III 1 Lebensdokumente von Wilhelm Lauer .................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Privater und gesellschaftlicher Bereich .......................................................................................... 5 1.2 Beruflicher Bereich ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2.1 Wilhelm Lauer als Wissenschaftler ......................................................................................... 6 1.2.2. Wilhelm Lauer in Leitungsfunktionen ................................................................................... 16 1.2.3 Wilhelm Lauer als Gutachter ................................................................................................ -

Contents 3 7 13 14 17 21 31 34 Dear Map Friends

BIMCC Newsletter N°19, May 2004 Contents Dear Map Friends, Pictures at an Ever since the creation of the BIMCC in 1998, President Wulf Exhibition (I—III) 3 Bodenstein has tried to obtain my help in running the Circle and, in particular, in editing the Newsletter. But I knew I could not possibly Looks at Books meet his demand for quality work, while being professionally active. (I - IV) 7 Now that I have retired from Eurocontrol, I no longer have that excuse, and I am taking over from Brendan Sinnott who has been the Royal 13 Newsletter Editor for over two years and who is more and more busy Geographical at the European Commission. Society Henry Morton When opening this issue, you will rapidly see a new feature: right in 14 the middle, you will find, not the playmap of the month, but the Stanley ”BIMCC map of the season”. We hope you will like the idea and present your favourite map in the centrefold of future Newsletters. BIMCC‘s Map 17 of the Season What else will change in the Newsletter? This will depend on you ! After 18 issues of the BIMCC Newsletter, we would like to have your Mapping of the 21 views: what features do you like or dislike? What else would you like Antarctic to read? Do you have contributions to offer? Please provide your feedback by returning the enclosed questionnaire. International Should you feel ready to get further involved in supporting the News & Events 31 organisation and the activities of the Circle, you should then volunteer to become an “Active Member”, and come to the Extraordinary Auction General Meeting; this meeting, on 29 October 2004 after the BIMCC Calendar 34 excursion (see details inside) will approve the modification of the BIMCC statutes (as required by Belgian law) and agree the Enclosure — nomination of Active Members to support the Executive Committee. -

Topographic Maps Fields

Topographic Maps Fields • Field - any region of space that has some measurable value at every point. • Ex: temperature, air pressure, elevation, wind speed Isolines • Isolines- lines on a map that connect points of equal field value • Isotherms- lines of equal temperature • Isobars- lines of equal air pressure • Contour lines- lines of equal elevation Draw the isolines! (connect points of equal values) Isolines Drawn in Red Isotherm Map Isobar Map Topographic Maps • Topographic map (contour map)- shows the elevation field using contour lines • Elevation - the vertical height above & below sea level Why use sea level as a reference point? Topographic Maps Reading Contour lines Contour interval- the difference in elevation between consecutive contour lines Subtract the difference in value of two nearby contour lines and divide by the number of spaces between the contour lines Elevation – Elevation # spaces between 800- 700 =?? 5 Contour Interval = ??? Rules of Contour Lines • Never intersect, branch or cross • Always close on themselves (making circle) or go off the edge of the map • When crossing a stream, form V’s that point uphill (opposite to water flow) • Concentric circles mean the elevation is increasing toward the top of a hill, unless there are hachures showing a depression • Index contour- thicker, bolder contour lines on contour maps, usually every 5 th line • Benchmark - BMX or X shows where a metal marker is in the ground and labeled with an exact elevation ‘Hills’ & ‘Holes’ A depression on a contour map is shown by contour lines with small marks pointing toward the lowest point of the depression. The first contour line with the depression marks (hachures) and the contour line outside it have the same elevation. -

Gradual Generalization of Nautical Chart Contours with a B-Spline Snake Method

GRADUAL GENERALIZATION OF NAUTICAL CHART CONTOURS WITH A B-SPLINE SNAKE METHOD BY DANDAN MIAO BS in Geographic Information Systems, Wuhan University, 2009 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Ocean Engineering September, 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2014 Dandan Miao This thesis has been examined and approved. Dr. Brian Calder, Associate Research Professor of Ocean Engineering Dr. Kurt Schwehr Affiliate Associate Professor of Ocean Engineering Dr. Steve Wineberg Lecturer, Mathematics and Statistics Date v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was sponsored by NOAA grant NA10NOS400007, and supported by the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping. Professor Larry Mayer introduced me to the world of Ocean Mapping, and taught me new information about geological oceanography; Professor Brian Calder initiated this study and has always been able to selflessly help me with any questions; Professor Steven Wineberg gave me many insights of how to transfer math concepts to graphic behavior; Professor Kurt Schwehr helped me with many intelligent thoughts and suggestion about computer programming implementation. I am grateful for all their selfless help and patience, and I would like to thank all of them for their guidance, encouragement and proof-reading of this thesis: without them and CCOM’s support, this work would not have happened. Finally, I would like to thank my parents and friends, for encouragement and trust. Your love and faith gave me the strength to keep holding on and finally make it work! Love you all! With greatest thankfulness, Dandan Miao vi TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. -

The Mercator Projection: Its Uses, Misuses, and Its Association with Scientific Information and the Rise of Scientific Societies

ABEE, MICHELE D., Ph.D. The Mercator Projection: Its Uses, Misuses, and Its Association with Scientific Information and the Rise of Scientific Societies. (2019) Directed by Dr. Jeff Patton and Dr. Linda Rupert. 309 pp. This study examines the uses and misuses of the Mercator Projection for the past 400 years. In 1569, Dutch cartographer Gerard Mercator published a projection that revolutionized maritime navigation. The Mercator Projection is a rectangular projection with great areal exaggeration, particularly of areas beyond 50 degrees north or south, and is ill-suited for displaying most reference and thematic world maps. The current literature notes the significance of Gerard Mercator, the Mercator Projection, the general failings of the projection, and the twentieth century controversies that arose as a consequence of its misuse. This dissertation illustrates the path of the institutionalization of the Mercator Projection in western cartography and the roles played by navigators, scientific societies and agencies, and by the producers of popular reference and thematic maps and atlases. The data are pulled from the publication record of world maps and world maps in atlases for content analysis. The maps ranged in date from 1569 to 1900 and displayed global or near global coverage. The results revealed that the misuses of the Mercator Projection began after 1700, when it was connected to scientists working with navigators and the creation of thematic cartography. During the eighteenth century, the Mercator Projection was published in journals and reports for geographic societies that detailed state-sponsored explorations. In the nineteenth century, the influence of well- known scientists using the Mercator Projection filtered into the publications for the general public. -

An Analysis of Selected Junior High School Geography Textbooks in Relation to Their Treatment of Certain Basic Geographic Concepts

This dissertation has been 63—2532 microfilmed exactly as received McFARREN, George Allen, 1930- AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL GEOGRAPHY TEXTBOOKS IN RELATION TO THEIR TREATMENT OF CERTAIN BASIC GEOGRAPHIC CONCEPTS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1962 Geography University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL GEOGRAPHY TEXTBOOKS IN RELATION TO THEIR TREATlffiNT OF CERTAIN BASIC GEOGRAPHIC CONCEPTS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By George Allen MeFarren, B. A., M. Ed. The Ohio State University 1962 Approved by Department of Education ACraJOWLEDGMEMTS In making this study, the .writer is indebted to many people, and to all he is greatly appreciative. To the nublishers who supplied the textbooks used in this study and to the administrative staffs of the school systems contacted, the uriter expresses his g ra titu d e . To rry ad^viser, Dr, Robert E, Jewett, I wish to express my snecial thanlcs for his endless coun-el, encouragement, and aid during my three years at The Ohio State University, A snecial expression of gratitude is extended to the two members of the reading committee of this dissertation. Dr, Fred A, Carlson and Dr. Hugh Laughlin. Their aid and suggestions have been greatly appreciated. To my mother and father, whose sacrifices, encouragement, and help have made higher education possible, I am forever thankful and appreciative. Also to my "second parents," Harold and Ruth, I wish to express my gratitude for their help and encouragement.