Reframing Israel-Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

SPRING 2008 R.A.C.E.Link

SPRING 2008 R.A.C.E.link TABLE OF CONTENTS RACE EDITORIAL 2 COORDINATING COMMITTEE Yasmin Jiwani NO ACADEMIC EXERCISE 3 Sedef Arat-Koc Sunera Thobani Associate Professor, Department of Politics and Public Administration, Ryerson University THE CAMP: A PLACE WHERE LAW HAS DECLARED 9 THAT THE RULE OF LAW DOES NOT OPERATE Enakshi Dua Sherene Razack Associate Professor, School of Women’s Studies, York University UPDATE ON THE TAYLOR BOUCHARD COMMISSION Charmaine Nelson ON ‘REASONABLE ACCOMMODATION’ 18 Associate Professor, Art History & Gada Mahrouse Communication Studies, McGill University Sherene Razack ECENT UBLICATIONS OF NTEREST R P I 22 Professor, Department of Sociology & Equity compiled by Ainsley Jenicek Studies, OISE, University of Toronto THROUGH THE LENS: FILMS ON TERRORISM 25 Sunera Thobani Ezra Winton Associate Professor, Centre for Research in Women Studies & Gender Relations, University of British Columbia MEMBERSHIP & CONFERENCE ANNOUNCEMENT 26 Yasmin Jiwani UPCOMING CONFERENCES 34 Associate Professor, Communication Studies, compiled by Ainsley Jenicek and Rawle Agard Concordia University R.A.C.E.link R.A.C.E.link EDITORIAL Yasmin Jiwani Welcome to the 2008 issue of RACE-Link. More than a newsletter but not quite a journal, RACE-Link at best constitutes a quasi-journal. In this issue, we continue to plot the lines defining race in its contemporary configurations in the post 9/11 Canadian context. This issue begins with Sunera Thobani’s article ‘No Academic Exercise’ tracing the highly problematic notion of academic freedom. Thobani calls attention to the lack of such freedom in voicing dissent against the ongoing War on Muslim bodies. She underlines the tenuous position of women of colour in the academy whose grounded knowledge is neither validated nor their critique acknowledged. -

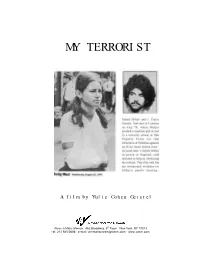

My Terrorist

MY TERRORIST A film by Yulie Cohen Gerstel Women Make Movies · 462 Broadway, 5th Floor · New York, NY 10013 Tel: 212.925.0606 · e-mail: [email protected] · www.wmm.com MY TERRORIST film synopsis Fahad Mihyi, a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and Yulie Cohen, a sixth-generation Israeli, first encountered one another in August 1978, when Mihyi pointed a machine gun at the El Al flight attendant in a terrorist attack. Twenty-three years later, in an effort to help break the cycle of violence, Yulie considers writing a letter in support of Mihyi's parole, thus thrusting herself into the turbulent world of Middle East politics. Growing up in an upper middle-class neighborhood in Israel, she served in the military and was a proud citizen of her country. After working as a photojournalist and visiting the occupied territories along the Gaza Strip, Gerstel came to realize that both Israelis and Palestinians played a role in perpetuating the cycle of hostility and bloodshed. It became her goal to stand up as a survivor and call for reconciliation on each side. Winner of a Special Jury Prize at the Jerusalem International Film Festival, and nominated for the Silver Wolf award at the Amsterdam International Documentary Film Festival, My Terrorist asks hard questions about the meaning of forgiveness and hate, the inevitability of violence and, just possibly, about the chance of reconciliation between Palestinians and Israelis. film credits Director/Producer: Yulie Cohen Gerstel Editor: Boaz Lion Cinematographer: Oded -

YARON SHEMER E-Mail: [email protected]

April 2015 VITA YARON SHEMER e-mail: [email protected] Work: UNC-Chapel Hill Office phones: (direct) 919/962-5428 Department of Asian Studies (departmental): 919-962-4294 CB # 3267, New West 109, Office fax: 919/843-7817 Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3267 Home Phone & Fax: 919/929-1692 Home: 839 Shady Lawn Rd. Chapel Hill, N.C. 27514 EDUCATION 2005: Ph.D. in Radio-Television-Film (with portfolio in Cultural Studies), The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX. 1991: M.A. in Radio-Television-Film, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX. 1983: B.F.A. in Film/TV, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2008 to present: Levine/Sklut Fellow in Jewish Studies and Associate Professor of Israel Cultural Studies and Modern Hebrew, Department of Asian Studies, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. 2002 – 2008: Senior Lecturer, Department of Middle Eastern Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX. 1991 – 2002: Lecturer, Department of Middle Eastern Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX. Summer 2002: Visiting Lecturer, Western Consortium Summer Intensive Middle Eastern Languages Institute, The University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Summer 1997: Visiting Lecturer, Western Consortium Summer Intensive Middle Eastern Languages Institute, The University of California, Berkeley, CA. PUBLICATIONS (<R> = refereed) Books Identity, Place, and Subversion in Contemporary Mizrahi Cinema in Israel. The University of Michigan Press, 2013. R Articles and Chapters “From Chahine’s Alexandria…Why to Salata Baladi and Jews of Egypt: Rethinking Egyptian Jews’ Cosmopolitanism, Belonging, and Nostalgia in Cinema.” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication (MJCC). -

Profiles of Peace

Profiles of Peace Forty short biographies of Israeli and Palestinian peace builders who have struggled to end the occupation and build a just future for both Palestinians and Israelis. Haidar Abdel Shafi Palestinian with a long history of working to improve the health and social conditions of Palestinians and the creation of a Palestinian state. Among his many accomplishments, Dr. Abdel Shafi has been the director of the Red Crescent Society of Gaza, was Chairman of the first Palestinian Council in Gaza, and took part in the Madrid Peace Talks in 1991. Dr. Haidar Abdel Shafi is one of the most revered persons in Palestine, whose long life has been devoted to the health and social conditions of his people and to their aspirations for a national state. Born in Gaza in 1919, he has spent most of his life there, except for study in Lebanon and the United States. He has been the director of the Red Crescent Society in Gaza and has served as Commissioner General of the Palestinian Independent Commission for Citizens Rights. His passion for an independent state of Palestine is matched by his dedication to achieve unity among all segments of the Palestinian community. Although Gaza is overwhelmingly religiously observant, he has won and kept the respect and loyalty of the people even though he himself is secular. Though nonparti- san he has often been associated with the Palestinian left, especially with the Palestinian Peoples Party (formerly the Palestinian Communist Party). A mark of his popularity is his service as Chairman of the first Palestinian Council in Gaza (1962-64) and his place on the Executive Committee of “There is no problem of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) (1964-65). -

Medea of Gaza Julian Gordon Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Theater Honors Papers Theater Department 2014 Medea of Gaza Julian Gordon Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/theathp Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gordon, Julian, "Medea of Gaza" (2014). Theater Honors Papers. 3. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/theathp/3 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theater Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theater Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. GORDON !1 ! ! Medea of Gaza ! Julian Blake Gordon Spring 2014 MEDEA OF GAZA GORDON !1 GORDON !2 Research Summary A snapshot of Medea of Gaza as of March 7, 2014 ! Since the Summer of 2013, I’ve been working on a currently untitled play inspired by the Diane Arnson Svarlien translation of Euripides’ Medea. The origin of the idea was my Theater and Culture class with Nancy Hoffman, taken in the Spring of 2013. For our midterm, we were assigned to pick a play we had read and set it in a new location. It was the morning of my 21st birthday, a Friday, and the day I was heading home for Spring Break. My birthday falls on a Saturday this year, but tomorrow marks the anniversary, I’d say. I had to catch a train around 7:30am. The only midterm I hadn’t completed was the aforementioned Theater and Culture assignment. -

Israel Has Been Home to a Renaissance of Jewish Culture

INTRODUCTION Israel celebrates its 70th birthday this year, 2018, on 19 April. After 2,000 years of exile and persecution, the Jewish people have made up for lost time now that they finally have a state of their own again. Israel has flourished in its first 70 years of statehood and achieved more than many far older countries. Here are 70 of Israel’s achievements we are highlighting – from the sublime and world changing to the small but important: ISRAEL HAS ACHIEVED ITS CORE MISSION OF PROVIDING A STATE FOR THE JEWS WHERE THEY CAN BE FREE FROM PERSECUTION Israel, the only Jewish state, is open to all Jews. It serves as a lifeboat state for Jews from around the world. It provided refuge for many European Jews after the Holocaust, with 25% of the population in the 1960s being Holocaust survivors. If the Jewish people had had a state of their own in the 1930s, many more Jews would have been saved from the Holocaust. Israel survived an attack by 4 neighboring armies when it declared Independence in 1948. Israel has achieved peace with both Egypt and Newly formed Israel built an army to Jordan after multiple wars. defend itself with 50% of the soldiers being Holocaust survivors. In 1979 Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula in return for normalising relations and demilitarisation of the Sinai. This agreement ended any prospect of another general Arab-Israeli war and has been a cornerstone of regional stability for nearly 40 years. Israel and Jordan signed a peace agreement in 1994. Not only did Israel achieve a successful emergency rescue of 14,500 Ethiopian Jews, nearly the entire Jewish population of Ethiopia, in under 36 hours, but it also broke the world record of carrying the most passengers on a 747 or any flying vehicle in the world. -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts. -

“This Is the Kairos...”

Films & Books Find More Films, Books, and Other Resources at umhltf.org “This is the Kairos...” Resources for Israel-Palestine Education and Advocacy Occupation 101 Fast Times in Palestine, Pam Olson Thought-provoking documentary covers a wide Harrowing, funny, vivid, moving and inspiring range of topics – history from 1880s to now, personal story that opens a rare window onto obstacles to peace, role of the US, settlements, Palestinian life under Israeli occupation. Easy the Separation Wall, Gaza, and more. 90 mins. and engaging to read, a fascinating memoir. Find Watch online or purchase at: occupation101.tv at: pamolson.org or Amazon. The Stones Cry Out The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Ilan Pappe Powerful film speaks for Christian Palestinians Renowned Israeli historian offers impressive living with oppression and occupation for over archival evidence that, from its inception, Israel's 60 years, from the 1948 Nakba until today. 55 founding ideology was the forced removal of the mins. Find at: thestonescryoutmovie.com indigenous population. Indispensable for those interested in this region. Find at Amazon, etc. 5 Broken Cameras Critically-acclaimed, Oscar-nominated, and The Lemon Tree, Sandy Tolan deeply personal cinematic diary of life and This story of an extraordinary friendship non-violent resistance in a West Bank village spanning 35 years brings the Israeli-Palestinian surrounded by Israeli settlements. 94 mins. conflict down to its most human level, "This is the kairos, the moment of grace and opportunity, Find at Amazon, Watch -

Israel 2019 Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments are due to representatives of government ministries and agencies as well as many others from a variety of organizations, for their essential contributions to each chapter of this book. Many of these bodies are specifically cited within the relevant parts of this report. The inter-ministerial task force under the guidance of Ambassador Yacov Hadas-Handelsman, Israel’s Special Envoy for Sustainability and Climate Change of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Galit Cohen, Senior Deputy Director General for Planning, Policy and Strategy of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, provided invaluable input and support throughout the process. Special thanks are due to Tzruya Calvão Chebach of Mentes Visíveis, Beth-Eden Kite of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Amit Yagur-Kroll of the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Ayelet Rosen of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Shoshana Gabbay for compiling and editing this report and to Ziv Rotshtein of the Ministry of Environmental Protection for editorial assistance. 3 FOREWORD The international community is at a crossroads of countries. Moreover, our experience in overcoming historical proportions. The world is experiencing resource scarcity is becoming more relevant to an extreme challenges, not only climate change, but ever-increasing circle of climate change affected many social and economic upheavals to which only areas of the world. Our cooperation with countries ambitious and concerted efforts by all countries worldwide is given broad expression in our VNR, can provide appropriate responses. The vision is much of it carried out by Israel’s International clear. -

Measuring Israeli Democracy (2011)

Measuring Israeli Democracy (2011): Epistemological, Methodological, and Ethical Dilemmas Paper prepared for presentation at the WZB, Berlin, 23 January, 2012 Prof. Tamar Hermann* The Open University of Israel & the Israel Democracy Institute Draft, not for citation *Email address: [email protected] Personal homepage: http://www.openu.ac.il/Personal_sites/tamar-hermannE.html 1 This paper aims at presenting, from a reflective perspective, the various dilemmas facing the team conducting the Israeli Democracy Index annual research project in general and its 2011 edition1 in particular. After dealing generally with the issue of measuring democracy and contextualizing this project in the “universe” of similar measurements/indices/barometers, the article will focus on the epistemological, methodological, and ethical dilemmas to be dealt with when assessing—by surveying public opinion—the democratic qualities of the Israeli regime, which are closely linked, it will be maintained here, to its unique political system and complex political situation. This will be done with a number of illustrations and through references to findings of the latest, as well as previous, Israeli Democracy annual reports. Introduction: In a nutshell—why and how to measure democracy? Since the mid twentieth century, global political discourse has been idolizing democracy. This regime type is widely perceived as the only one which—at least in principle—respects the universally most highly cherished set of human rights and civil rights. Democracy in general and liberal democracy in particular are therefore almost unanimously considered as morally superior to all others regimes, past, present, and perhaps even future. Thus, today, especially in the West but also in other parts of the world, very few dare publicly to foster and legitimize any other form of government even if in fact they ideologically or practically do endorse it. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987.